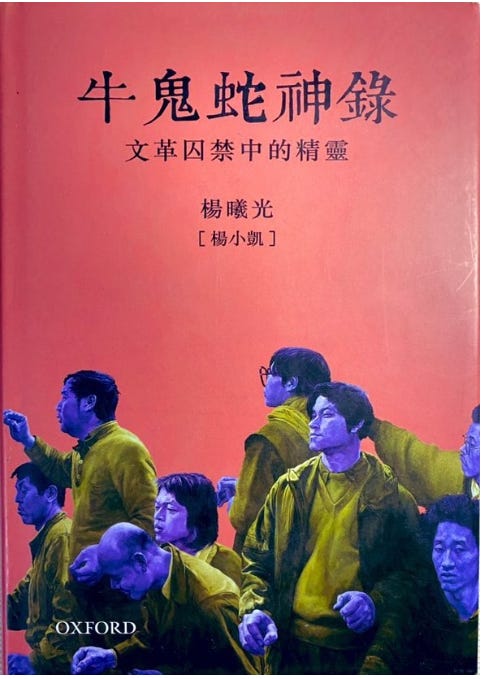

杨小凯的《牛鬼蛇神录》:中国的古拉格群岛 一部血泪交织的政治教科书

Yang Xiaokai’s Captive Spirits: China’s Gulag Archipelago – A Political Textbook Forged in Blood and Tears

作者:伍雷

By Wu Lei

The English translation follows below.

杨小凯先生(1948-2004)是中国著名的经济学家,他曾因新兴古典经济学与超边际分析理论的创见而两次获得诺贝尔经济学奖提名,被称为“离诺奖最近的华人经济学家”。今年7月7日是他去世21周年的纪念日。

但这位经济学家留给我们的一部不朽之书,却是这本《牛鬼蛇神录:文革囚禁中的精灵》。

阅读这本书的体验是如此独特。于我而言,一个最大的收获是认识到,在中国政治极度高压的时代,例如文革,都有那么多鲜活、具体的生命,并不隐瞒自己的政治追求。他们的言论,对中国社会的理解,甚至他们的喜怒哀乐、男欢女爱,都在书中生动地呈现,让人们了解到那一代中国人极具个性化的生存面貌。书中写到的政治犯们,他们的反抗精神和行动,以及为此付出的残酷代价,让人久久不能平静。

杨小凯原名杨曦光,于1948年出生于共产党的高级干部家庭。1968年,还在湖南上中学的他,因为一篇题为《中国向何处去?》的大字报,被以“现行反革命罪”判刑十年,先后在看守所、监狱、劳改农场服刑。《牛鬼蛇神录》一书,正是杨小凯对狱中十年所遇各种人物的真实描述。

极权之下 中国民间始终存在的政治反对传统

毛时代的中国大陆,仅仅湖南一地,就有多个反对共产党的民间地下政治组织,这完全超乎我的想象。

对我们这一代中国人来说,了解从1949年到1979年中国的民间思想,很多是来自类似《夹边沟记事》、《寻找林昭的灵魂》这样的作品,以及1980年代后的一些伤痕文学,而这是很不够的。事实上,在社会管制十分严厉的毛时代,中国也一直存在大量的民间政治反对组织。杨小凯在书中披露,仅湖南就有包括民主党、中国劳动党、大同党、反共救国军等政治反对组织。今天看来,这简直有点不可思议。

杨小凯的书让我们看到,在1949年到1979年之间,中国大陆的民间社会并没有被完全消灭——即使长期在地下状态,它也仍然存在。而这种民间反抗传统的始终存在,让人不由心生一种敬意与骄傲。试想,如果这种传统在社会被极端控制的时代都存在,那么在改革开放40年后的今天,无论遭受怎样的打压,它也一定会存在下去(当然存在的形式会有很大不同)。作为一个民间反对者,还有什么比看到这种传统曾活生生地存在,且始终存在,而更激动人心呢?

这些毛时代的政治反对人物,在《牛鬼蛇神录》中的代表性人物有刘凤祥、张九龙、粟异邦、杨学孟等人,以及他们的地下党——民主党、劳动党、反共救国军。在狱中遇到的这些政治犯,都受到了杨小凯发自内心的尊敬。这些人,也正是杨小凯后来写这本书的主要动机——他不想让这些有血有肉有思想的政治犯被历史湮没。他一定有为这些给他带来巨大心灵冲击的政治犯“立传”的强烈冲动和责任感,所以才对自己亲身经历的这些人的经历,竭尽所能地回忆。由于当时环境的限制,这些政治犯本人也不会向杨小凯披露全部的事情经过——这样的披露有可能付出生命的代价。后人要感谢杨小凯,他通过不同的人物、场景、语言以及细节,尽力拼凑出了那些政治犯生动完整的画像。

这样看来,杨小凯不仅仅是优秀的经济学家,也是优秀的史家。他在笔下把这些逝去的政治犯们复活了。本书的英文译名是Capitive Spirits,直译就是“狱中精灵”,书的名字似乎就是最好的说明和解释。他笔下的这些人,代表着人之为人最宝贵的品质之一,那就是反抗专制。

在本书的前言中,杨小凯写道:“当然贯穿全书最重要的问题是:秘密结社组党的反对派运动在中国能不能成功,它在文革中起了什么作用?相关的问题则是:多如牛毛的地下政党在文革中尽管非常活跃,但为什么,他们不可能利用那种大好机会取得一些进展?”

请注意,杨小凯描述当时的地下政党,用的词语是“多如牛毛”!

而他提出的问题。一直要到此书的最后两三章,作者在劳改队接触到政治犯秘密结社的问题时才被挑明。历史学家、政治学家们至少可以从这些真实的故事去理解,在极端高压治下,中国秘密结社的背景、意识形态以及活动方式。

看完这本书,我对书中提到的政治犯,那些身影,冷峻的表情,死刑之前的绝望或失望,都久久不能忘怀。作为一名人权律师,这些年,我在大陆接触了很多类似的政治犯,有些朋友至今仍然关押在监狱,有的朋友则失踪多年,有的朋友已经过世。对类似的表情,乃至他们的性格、动作,我都太熟悉了。他们的品质、学识,以及信心和不屈服的品格,都可以说是这个民族不朽的精灵。

我甚至惊奇地发现,书中人物的言语、动作、神情,都不会让我感到很陌生——即使历史如此残酷,但这种政治犯的气质似乎还是被一代一代人传了下来。就像我认识的那些中国政治犯一样,他们表露出的自信,对历史的洞察感,以及对于专制的极度反感,都和前辈出奇地相似!

惨烈的狱中政治犯之死

在中国,一些民间人士谈起南非总统曼德拉,会调侃说,如果曼德拉生活在同时代的中国,恐怕就会死在监狱中。确实,政治犯的待遇,会因当权者的残酷程度而不相同。书中杨小凯所遇到的政治犯,就遭遇了最残酷的镇压——枪毙,这也是政治反对者面临的最极端处境。这也让我认识到,极权体制的本质之一,就是不能真正容忍异议的存在。

杨小凯的书中写到政治犯张九龙之死:

“1970年的一打三反运动中,张九龙不幸成为受害者。那次运动中,所有判处死刑缓期二年执行的政治犯,全被从劳改单位拉出来,立即执行死刑。我是从张九龙的两个同案犯王少坤和毛治安那里听到这个消息的。我当时正在挑土,扁担从我肩头滑下来,恐惧、仇恨和悲痛使我直想呕吐。那天后我多次想象他临死前的形象,很长一段时间,我的脑海不能摆脱他的面孔,他下棋时忧郁、专注地拿起一个棋子的形象,接着又是预审后他那苍白冷酷的面色。”

杨小凯写到曾组织“民主党”的政治犯粟异邦之死:当粟被宣布死刑后,被公安人员厉声问道还有什么要说的时,粟异邦的回答使所有人都大吃一惊。“我反共产党,却不反人民,反共产党是为了人民,人民反对你们。” “‘闭住你的狗嘴,上死镣!’办公室传来叮叮当当的铁镣声,接着是锤子钉铆钉的声音。声音是如此清脆,深重,划破寂静的夜空,使人惊心动魄。”

“他(指粟异邦)那天还不等(公开)宣判完毕,就在东风广场十几万人面前突然大呼‘打倒共产党!打倒毛泽东!’。我们对发生的事还没有完全反应过来,只见粮子们(军警)都朝他跑去。我在他的身边,渐渐看清了那场景。他被上了死绑,头很难抬起来。但是他却拼命昂起头来呼喊。这时几个粮子用枪托打他的头,他的声音还没有停止。有个粮子用枪刺向他的口里,顿时鲜血直喷,但他还在奋力挣扎。这时另一支枪刺插入他的嘴中,金属在牙齿和肉中直绞的声音使我全身发麻,还不到宣判大会结束,他已死在血泊中。”

杨小凯遇到的另一位政治犯叫刘凤祥,是原湖南日报主编,他们在狱中成为好友,他对杨小凯影响巨大。他在书中写道:

“(死刑)布告上说雷特超、刘凤祥为首组织反革命组织中国劳动党,煽动上山为匪,妄图颠覆无产阶级专政。这对我无异于听到一声晴天霹雳,一阵悲痛从我心中涌起。我问苍天,为什么这么优秀的政治家,这么正直的人却被残酷地杀害?最可悲的是,当局像在干一件暗杀的勾当,绝大多数人不知道刘凤祥的政治观点,甚至不知道他是谁。”

多年之后,杨小凯仍然无法平静自己的内心。他对这些政治犯抱有深深的同情,另一个原因,是他自己本身就是政治犯,只是侥幸地活了下来,才有机会讲出这些狱友的故事。

从1949年至今,从王炳章到高智晟,到伊力哈木,到刘晓波、许志永、丁家喜、郭飞雄,这一个个中国政治犯的存在,告诉我们,虽然时代在变,但极权政治的本质从来没有变化过,对政治犯残酷镇压的传统也始终存在。而政治犯无疑就是一个国家法治状况的晴雨表,有政治犯的国家断然没有法治,只有权力的耀武扬威。

中国人是被驯服的人群吗?

《牛鬼蛇神录》不仅仅是一部不朽的文学作品,更是一本渗透着生命与血泪的政治教科书。事实上,这本书还进一步回答了一些问题,那就是中国人是否勇敢的问题,以及中国社会是不是真的稳定的问题。

杨小凯在书中写到:“共产党朝代的稳固不是因为它的开明,而是因为它的残酷。两三年后,沈子英(另一名狱友)又被加了四年徒刑。看样子,当局是绝不会让他这一辈子再回到社会上去了。他每次快满刑,马上被加刑。这大概是为什么社会上看不到批评共产党的人,全世界都以为中国人本性驯服,对共产党毫无尖锐批评的原因。从沈子英身上,我看到中国人的本性并不是那么驯服的,至少不像人们在中国社会上看到的那样驯服。保持着中国人向当局挑战性格的人,充满着劳改队和监狱。”

“人民不需要自由”(歌手李志反讽的歌词),果真如此吗?真正熟悉中国社会状况的朋友,大体会认同杨小凯的观察。不仅杨小凯时代如此,杨小凯之后的1989年天安门广场运动,2015年的709大抓捕,以及中国历次的政治运动,都证明了中国人并不缺乏反抗的勇气。在中国,似乎看不到反抗者的原因,恰恰是残酷的镇压完全压制了政治反对力量,有影响力和行动力的政治反对者,无一例外都受到了各种手段的镇压。今天与过去不同的只是:当局稍微变“文明”了一点,他们已经学会娴熟地利用司法手段,把各种政治犯送入监狱。

这也再次提醒我们,对于社会的观察,需要高度重视一国的人权保护状况,尤其是政治犯的人权状况。杨小凯后来能取得经济学研究的巨大成就,不乏他自己的努力,包括在监狱坚持学习英语和高等数学,但大概也离不开他对于书中所描述的苦难本身最深刻的体验。

本书与少年杨小凯“中国向何处去”的疑问

1967年,19岁的中学生杨小凯(时名杨曦光)写了《中国向何处去?》这篇长文,并改变了他的一生的命运。在文章中,他写道:“中国已经形成了新的特权阶级,他们压迫剥削人民。中国的政体与马克思当年设想的巴黎公社民主毫无共同之处。所以中国需要一次新的暴力革命推翻特权阶级,重建以官员民选为基础的民主政体。”

因这篇文章,杨小凯被判刑十年。又因为狱中的十年,才有了这部奇书《牛鬼蛇神录》。可以说,没有《中国向何处去?》,就没有《牛鬼蛇神录》,甚至就没有日后的经济学家杨小凯。

在书中一开始,杨小凯就提到自己一生中身份的三个转变:信奉共产党思想的高干子弟——十年牢狱变革自己的思想——经济学博士。他曾经受共产党的极深影响,思想第一次受到重击,是他的哥哥和舅舅被划为右派,而他身为高干的父亲,因为反对大跃进而被打成右倾机会主义分子,被下放农村。这些家庭剧变给青年杨小凯带来巨大的冲击。促使他对自己的思想进行自我革命。他想搞清楚,“文革中城市居民与共产党干部发生激烈冲突的真正原因”。

真正给予杨小凯历炼,促使他思想完成转变的却是长达十年的牢狱生活。杨小凯用自己的眼睛和头脑,甚至几乎用自己的生命体验了最真实的中国。他描写了自己真实接近死刑的恐惧,他不惜笔墨书写他的难友们。那些形形色色的“狱中精灵”所组成的最真实的中国社会:既有各种各样的反革命犯(政治犯),也有盗窃犯,有不同意公私合营而上访入狱的民营企业家,当然也有传授给杨小凯知识的大学老师,工程师。

杨小凯提到,1970年代初,他在监狱里彻底放弃了对马克思列宁主义的信仰,而成为一个极力反对革命民主主义,支持现代民主政体的人。“从杨曦光的眼睛,读者会看到中国的古拉格群岛上,形形色色的精灵是如何重新铸造了杨曦光的灵魂。”

在书中,杨小凯也用充满赞赏的语气,描写被公私合营的小企业主。他真心赞扬市场交易,赞扬小企业主的生产效率和财富积累。他毫不掩饰对于计划经济,对于不保护人民财产的各种制度的痛恨。他说到,1949年之后农民因为税负过重而怀念国民党时代,痛骂毛泽东——这些所反映的,不就是现代经济学中最重要的基础理念吗?包括保护私有财产;促进公平竞争;增加市场活力……更重要的是,他对于那些因自由表达而入狱的人,对在监狱内疯疯癫癫的民国时期律师,对无法自由表达而只能趁着做苦力发表“联合国”演讲的犯人,以及那位在看守所虔诚敬拜上帝的天主教徒,都充满敬佩。书中的那些细节描写,也代表着杨小凯自己憧憬、追求的价值。

而保护私有财产、尊重市场;表达自由、信仰自由以及司法公正,组党结社自由,这些不都是现代民主社会最重要的价值基础吗?

到了这里,我们似乎不再遗憾杨小凯的书里没有给中国的社会文明转型提供路径答案。 Capitive Spirits,狱中精灵,书名就是答案。这是一种精神的力量,也表达了历史演变过程中前进的方向。

或许,中年的杨小凯在这本书中所表达的,就是少年时期他“中国向何处去”之问的答案。通过书里这些具体人物的遭遇,相信每一个读者心中也都会产生答案:中国一定要废除极权专制,走向保护私有财产、保护自由、促进平等的民主宪政国家。除此之外,别无他途。

(作者伍雷,原名李金星,中国人权律师,现旅居日本。)

本期推荐档案:

杨小凯:

Yang Xiaokai’s Captive Spirits: China’s Gulag Archipelago – A Political Textbook Forged in Blood and Tears

By Wu Lei

Yang Xiaokai (1948-2004) was a renowned Chinese economist. He received two nominations for the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his groundbreaking theories of new classical economics and super marginal analysis, earning him the title “the Chinese economist closest to the Nobel Prize.” July 7 marked the 21st anniversary of his passing.

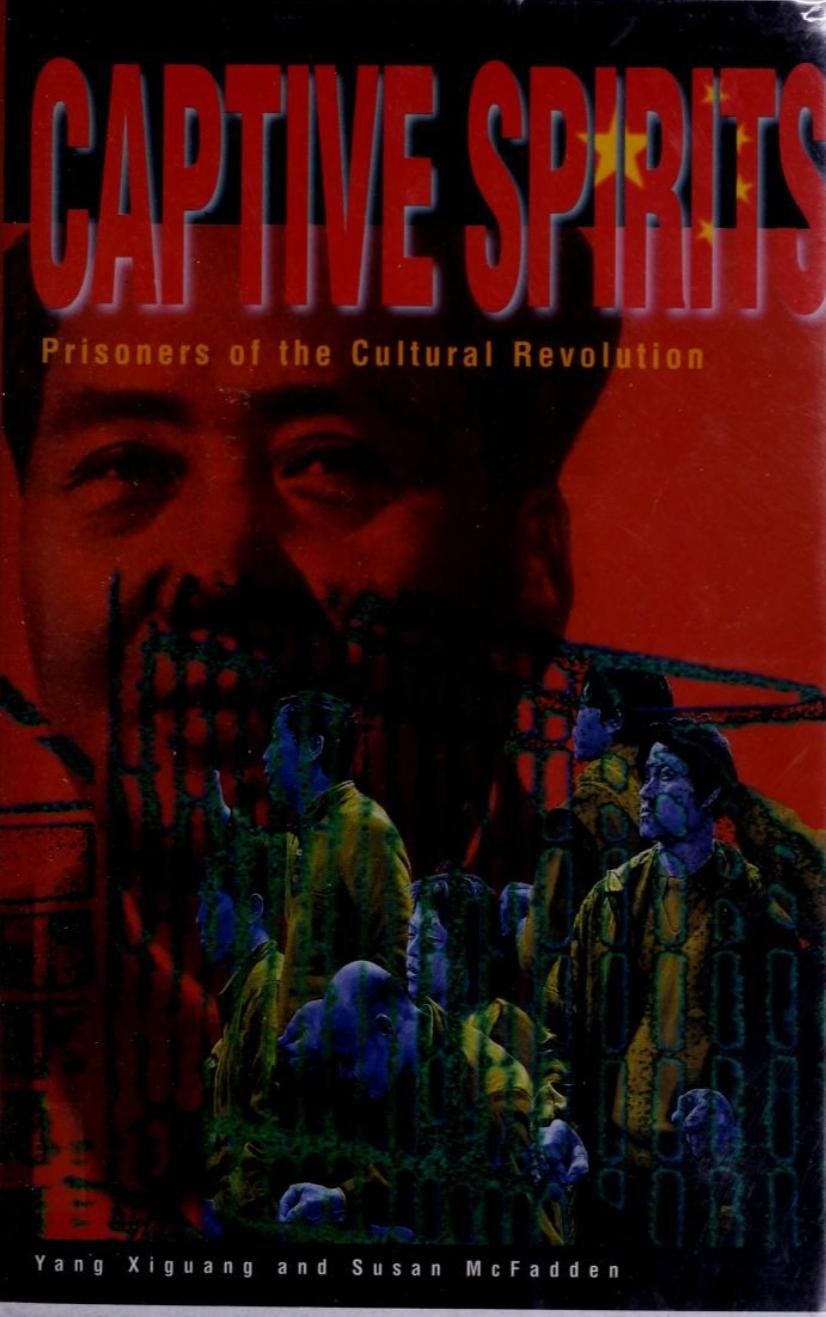

However, the enduring book this economist left us is not an economic treatise; it is Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution

Reading this book offers a truly unique experience. For me, the most significant realization was that even during China’s era of extreme political oppression, like the Cultural Revolution, countless vibrant, individual lives openly pursued their political aspirations. Their statements, their understanding of Chinese society, and even their joys, sorrows, and romantic relationships are vividly presented in the book, allowing readers to grasp the highly individualized existence of that generation. The book’s descriptions of political prisoners, their spirit and acts of resistance, and the brutal price they paid, leave readers deeply unsettled.

Yang Xiaokai, originally named Yang Xiguang, was born in 1948 into a high-ranking Communist Party cadre family. In 1968, while still a middle school student in Hunan, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for “counter-revolutionary crimes” due to a big-character poster titled “Whither China?” He served his sentence in various detention centers, prisons, and labor camps. Captive Spirits is Yang’s account of the diverse individuals he encountered during his decade in prison.

The Enduring Tradition of Political Dissent Under Totalitarian Rule in China

It is surprising that during the Mao era in Mainland China, even in Hunan province alone, multiple unofficial, underground political organizations opposed the Communist Party.

For our generation of Chinese people, much of our understanding of popular thought in China from 1949 to 1979 comes from works like Chronicle of Jiabiangou and In Search of Lin Zhao's Soul, along with other so-called “scar literature” from after the 1980s. This is far from sufficient. In fact, during the Mao era, when social control was extremely strict, a large number of unofficial political opposition organizations consistently existed in China. Yang Xiaokai reveals in his book that Hunan alone hosted political opposition groups, including the Democratic Party, the Chinese Labor Party, the Datong Party, and the Anti-Communist National Salvation Army. Today, this seems almost unbelievable.

Yang Xiaokai’s book shows us that between 1949 and 1979, Chinese civil society was not completely eradicated; even if it primarily operated underground, it persisted. The constant presence of this tradition of popular resistance inspires a sense of respect and pride. Just imagine, if this tradition existed even during a period of extreme social control, then today, 40 years after reform and opening up, it will certainly continue to exist, regardless of the suppression it faces (though its forms will differ greatly). As a civilian dissident, what could be more inspiring than seeing that this tradition once existed vibrantly and always has?

Representative figures of these Mao-era political dissidents in Captive Spirits include Liu Fengxiang, Zhang Jiulong, Su Yibang, and Yang Xuemeng, along with their underground parties—the Democratic Party, the Labor Party, and the Anti-Communist National Salvation Army. Yang Xiaokai held genuine respect for these political prisoners he met in jail. These individuals were also Yang Xiaokai’s primary motivation for writing this book—he did not want these flesh-and-blood, thoughtful political prisoners to be forgotten by history. He must have felt a strong urge and sense of responsibility to remember these political prisoners who had such a profound impact on him, which is why he meticulously recalled the experiences of those he personally encountered. Due to the limitations of the environment at the time, these political prisoners themselves would not have disclosed the full extent of their stories to Yang Xiaokai, as such disclosures could have cost them their lives. Future generations should thank Yang Xiaokai; through various characters, scenes, language, and details, he painstakingly pieced together vivid and complete portraits of those political prisoners.

Seen in this light, Yang Xiaokai was not only an excellent economist but also an excellent historian. He resurrected these departed political prisoners through his writing. The English translation of the book’s title, Captive Spirits, seems to be a great encapsulation of the book. The people he writes about represent one of humanity’s most precious qualities: resistance to tyranny.

In the book’s foreword, Yang Xiaokai wrote: “Of course, the most important question running throughout the book is: Can the opposition movement of secret societies and party formations succeed in China, and what role did it play during the Cultural Revolution? A related question is: Why, despite being extremely active during the Cultural Revolution, were the countless underground parties unable to make any progress using such a great opportunity?"

Please note that Yang Xiaokai uses the phrase “as numerous as ox hairs” (too many to count) to describe the underground parties at the time!

The questions he raises are only fully revealed in the last few chapters of the book, when the author encounters the issue of secret political societies among prisoners in the labor camps. Historians and political scientists can at least use these true stories to understand the background, ideology, and methods of operation of secret societies in China under extreme high-pressure rule.

After finishing this book, I cannot forget the political prisoners mentioned: their figures, their stern expressions, and their despair or disappointment before execution. As a human rights lawyer, over the years, I have encountered many similar political prisoners in mainland China. Some friends are still imprisoned today, some have been missing for years, and some have passed away. I am all too familiar with similar expressions, as well as their personalities and actions. Their qualities, knowledge, confidence, and unyielding character can truly be described as the immortal spirits of this nation.

I was even surprised to find that the words, actions, and expressions of the characters in the book do not feel unfamiliar to me. Even though history was so brutal, the temperament of these political prisoners seems to have been passed down from generation to generation. Just like the Chinese political prisoners I know, their expressed confidence, their insights into history, and their extreme aversion to tyranny are remarkably similar to those of their predecessors!

The Tragic Deaths of Political Prisoners

In China, when some private citizens discuss former South African president Nelson Mandela, they jokingly say that if Mandela had lived in China during the same period, he would probably have died in prison. Indeed, the treatment of political prisoners varies with the cruelty of those in power. The political prisoners Yang Xiaokai encountered in his book faced the most brutal suppression—execution by firing squad—which is also the most extreme situation political dissidents face. This also made me realize that one of the essential natures of a totalitarian system is its inability to truly tolerate dissent.

Yang Xiaokai writes about the death of political prisoner Zhang Jiulong in his book:

“During the 1970 ‘One Strike, Three Anti’ campaign, Zhang Jiulong unfortunately became a victim. In that campaign, all political prisoners who had received death sentences with a two-year reprieve were dragged out of the labor camps and immediately executed. I heard this news from Zhang Jiulong’s two co-defendants, Wang Shaokun and Mao Zhian. I was carrying soil at the time, and the carrying pole slipped from my shoulder. Fear, hatred, and grief made me want to vomit. After that day, I often imagined him in his final moments. For a long time, I couldn’t get his face out of my mind—his melancholic, focused expression as he picked up a chess piece, and then his pale, cold face after the preliminary interrogation.”

Yang Xiaokai describes the death of political prisoner Su Yibang, who organized the “Democratic Party”: When Su was sentenced to death, the public security officers sternly asked if he had anything else to say. Su Yibang’s reply astonished everyone. ‘I oppose the Communist Party, but not the people. I oppose the Communist Party for the people. The people oppose you.’ ‘Shut your dog mouth, put on the death shackles!’ From the office came the clanging sound of iron shackles, followed by the sound of hammers nailing rivets. The sound was so clear, so profound, piercing the silent night sky, startling everyone.”

“That day, before the public pronouncement of his sentence was even finished, he (referring to Su Yibang) suddenly shouted ’Down with the Communist Party! Down with Mao Zedong!’ in front of tens of thousands of people in Dongfeng Square. We hadn’t fully reacted to what was happening when we saw the ‘liangzi’ (military police) all rush towards him. I was by his side and gradually saw the scene clearly. He was bound for execution, his head difficult to lift. But he desperately strained his neck to shout. At this point, several ‘liangzi’ struck his head with rifle butts, but his voice did not stop. One ‘liangzi’ thrust a bayonet into his mouth, and blood immediately spurted out, but he was still struggling fiercely. Then another bayonet was inserted into his mouth, and the sound of metal grinding against teeth and flesh made my whole body numb. Before the sentencing rally even ended, he had died in a pool of blood.”

Another political prisoner Yang Xiaokai encountered was Liu Fengxiang, former editor-in-chief of Hunan Daily. They became good friends in prison, and Liu had a profound influence on Yang Xiaokai. Yang writes in the book:

“The (death sentence) proclamation stated that Lei Techao and Liu Fengxiang had organized the counter-revolutionary organization, the Chinese Labor Party, instigated people to become bandits in the mountains, and attempted to overthrow the dictatorship of the proletariat. To me, this was like a bolt from the blue, and a surge of grief rose in my heart. I asked heaven, why such an excellent politician, such an upright person, was brutally murdered? The saddest thing is that the authorities acted like they were carrying out an assassination; most people didn’t know Liu Fengxiang’s political views, or even who he was.”

Years later, Yang Xiaokai still could not calm his inner turmoil. He felt deep sympathy for these political prisoners, partly because he himself was a political prisoner who fortunately survived, thus having the chance to tell the stories of his fellow inmates.

From 1949 to the present, from Wang Bingzhang to Gao Zhisheng, to Ilham Tohti, to Liu Xiaobo, Xu Zhiyong, Ding Jiaxi, and Guo Feixiong—the existence of these Chinese political prisoners tells us that although times change, the essence of totalitarian politics has never changed, and the tradition of brutal suppression of political prisoners has always existed. Political prisoners are undoubtedly a barometer of a country’s rule of law; a country with political prisoners certainly has no rule of law, only the blatant display of power.

Are Chinese People a Submissive Populace?

Captive Spirits is not merely an immortal literary work; it is a political textbook imbued with life and tears. In fact, this book further answers questions about whether Chinese people are brave and whether Chinese society is truly stable.

Yang Xiaokai writes in the book: “The stability of the Communist dynasty was not due to its enlightenment, but to its cruelty. Two or three years later, Shen Ziying (another inmate) was given an additional four years in prison. It seemed the authorities would never let him return to society in his lifetime. Every time his sentence was almost up, he would immediately receive an additional sentence. This is probably why no one criticizes the Communist Party in society, and the whole world thinks that Chinese people are inherently submissive and have no sharp criticism of the Communist Party. From Shen Ziying, I saw that the nature of Chinese people is not so submissive, at least not as submissive as people see in Chinese society. People who maintain the Chinese character of challenging authority fill the labor camps and prisons."

“The people don’t need freedom” (a sarcastic lyric by singer Li Zhi)—is that really true? Friends who are truly familiar with the situation in Chinese society will largely agree with Yang Xiaokai’s observation. This was not only true in Yang Xiaokai’s era, but also after him, the 1989 Tiananmen Square movement, the 709 crackdown in 2015, and various political movements in China have all demonstrated that Chinese people do not lack the courage to resist. The seeming absence of resistors in China is precisely because brutal suppression completely stifles political opposition. Influential and active political dissidents, without exception, have been suppressed by various means. The only difference today compared to the past is that the authorities have become slightly more civilized; they have learned to skillfully use judicial means to send various political prisoners to jail.

This also reminds us again that when observing society, we need to pay great attention to a country’s human rights protection status, especially the human rights status of political prisoners. Yang Xiaokai’s later enormous achievements in economic research were not without his own efforts, including his persistence in learning English and advanced mathematics in prison, but his great achievements are also inseparable from his deepest experience of the suffering described in the book.

This Book and Young Yang Xiaokai’s Question “Whither China?”

In 1967, 19-year-old middle school student Yang Xiaokai (then named Yang Xiguang) wrote the lengthy article “Whither China?” which changed the course of his life. In the article, he wrote: “A new privileged class has formed in China, which oppresses and exploits the people. China’s political system has nothing in common with the Parisian Commune democracy envisioned by Marx. Therefore, China needs a new violent revolution to overthrow the privileged class and rebuild a democratic political system based on elected officials.”

Because of this article, Yang Xiaokai was sentenced to ten years in prison. And it was because of those ten years in prison that this extraordinary book, Captive Spirits, came into being. It can be said that without “Whither China?”, there would be no Captive Spirits, and perhaps not even the economist Yang Xiaokai of later years.

At the beginning of the book, Yang Xiaokai mentions three transformations in his identity throughout his life: a high-ranking cadre’s son who believed in Communist ideology, followed by ten years of imprisonment that transformed his thinking, and finally, becoming an economics PhD. He was once deeply influenced by the Communist Party. His thought was first severely impacted when his elder brother and uncle were labeled as rightists, and his father, a high-ranking cadre, was denounced as a right-leaning opportunist for opposing the Great Leap Forward and sent down to the countryside. These family upheavals had a huge impact on the young Yang Xiaokai, prompting him to undergo a self-revolution of his own thinking. He wanted to understand “the real reasons for the fierce conflict between urban residents and Communist Party cadres during the Cultural Revolution.”

However, it was his ten years in prison that truly tempered Yang Xiaokai and prompted his intellectual transformation. Yang Xiaokai experienced the most authentic China with his own eyes and mind, almost even with his own life. He describes his own fear of truly facing the death penalty and spares no effort in writing about his fellow inmates. The most authentic Chinese society was composed of these diverse “captive spirits”: there were various types of counter-revolutionaries (political prisoners), as well as thieves, private entrepreneurs who went to prison for petitioning against public-private partnerships, and of course, university professors and engineers who imparted knowledge to Yang Xiaokai.

Yang Xiaokai mentioned that in the early 1970s, he completely abandoned his belief in Marxism-Leninism in prison and became a staunch opponent of revolutionary democracy, supporting a modern democratic political system. “Through Yang Xiguang’s eyes, readers will see how diverse spirits in China’s Gulag Archipelago re-forged Yang Xiguang’s soul.”

In the book, Yang Xiaokai also uses an appreciative tone to describe the small business owners whose enterprises were taken over by public-private partnerships. He genuinely praised market transactions and lauded the productivity and wealth accumulation of small business owners. He openly expressed his hatred for the planned economy and for various systems that did not protect people’s property. He states that after 1949, farmers, due to excessive taxation, longed for the Nationalist era and cursed Mao Zedong—don’t these reflections embody the most important fundamental concepts of modern economics? More importantly, he deeply admired those who were imprisoned for free expression. The detailed descriptions in the book also represent the values that Yang Xiaokai himself yearned for and pursued.

And aren’t the protection of private property, respect for the market; freedom of expression, freedom of belief, and judicial fairness; and freedom of association and party formation, all the most important foundational values of a modern democratic society?

At this point, we no longer seem to regret that Yang Xiaokai’s book does not provide a direct answer for China’s social and civil transformation. “Captive Spirits,” the title of the book, is the answer. This is a spiritual force, and it also expresses the way forward of historical evolution.

Perhaps what the middle-aged Yang Xiaokai expressed in this book is the answer to his youthful question, “Whither China?” Through the experiences of the specific individuals in the book, I believe every reader will also find an answer in their hearts: China must abolish totalitarian autocracy and move towards a democratic constitutional state that protects private property, freedom, and promotes equality. There is no other way.

(The author, Wu Lei, whose original name is Li Jinxing, is a Chinese human rights lawyer. He currently resides in Japan.)

Recommended archive:

Yang Xiaokai: Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution

Once again, and I seem to be the lone commenter and among the few viewers, more's the pity, thank you for outing the Crimes Against Humanity by the Chinese Communist Party.