“对自由的渴望,是无孔不入的压迫造成的” ——胡平谈1980年代长文《论言论自由》

“The yearning for freedom is born from pervasive oppression”—Hu Ping on his 1980s essay, “On Freedom of Speech”

民间档案馆系列访谈(1)

The China Unofficial Archives Interview Series No. 1

The English version follows below.

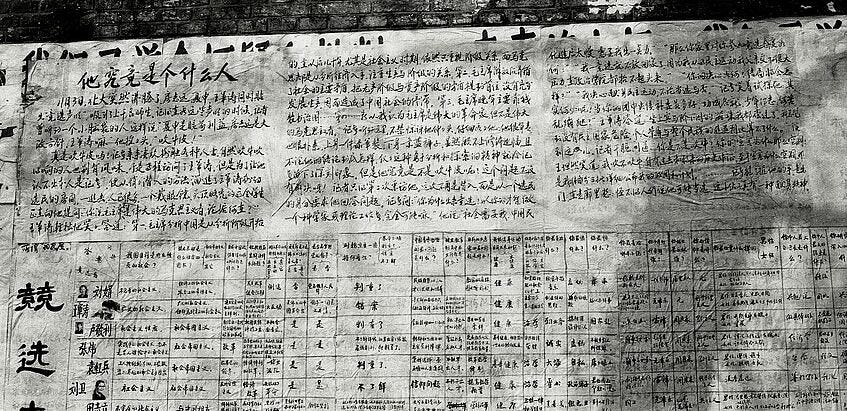

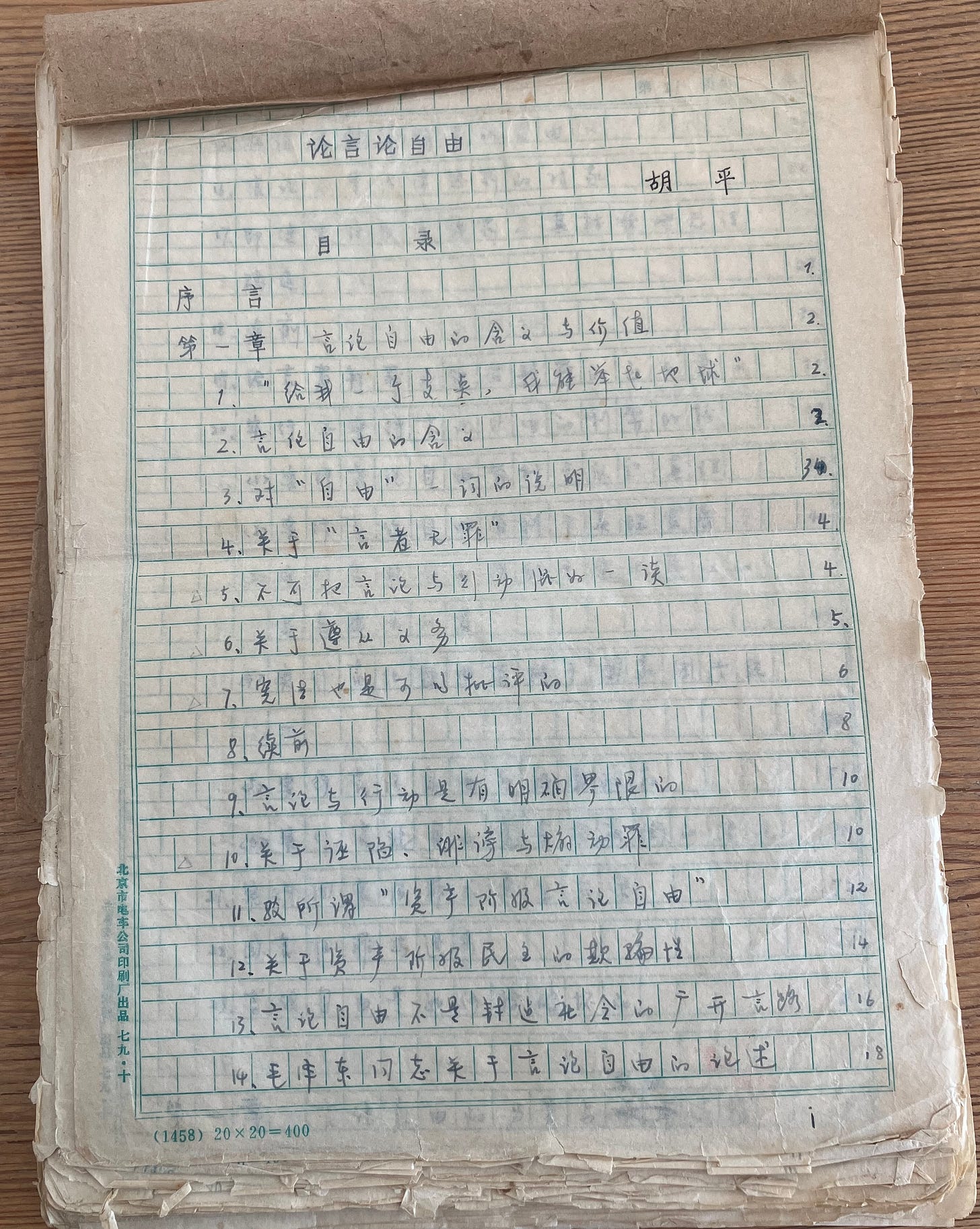

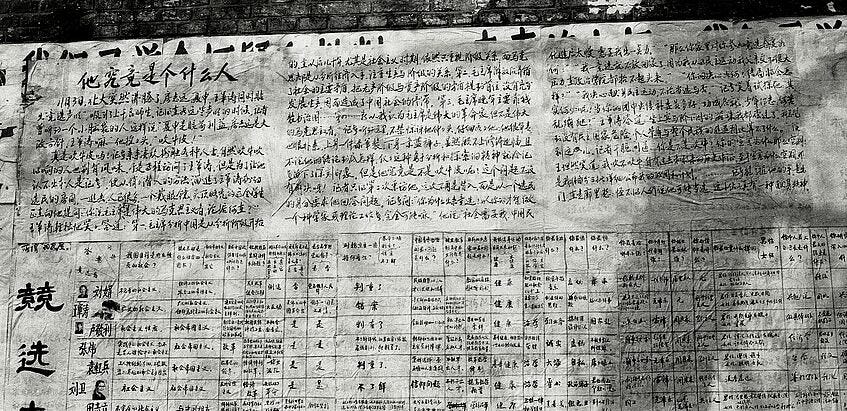

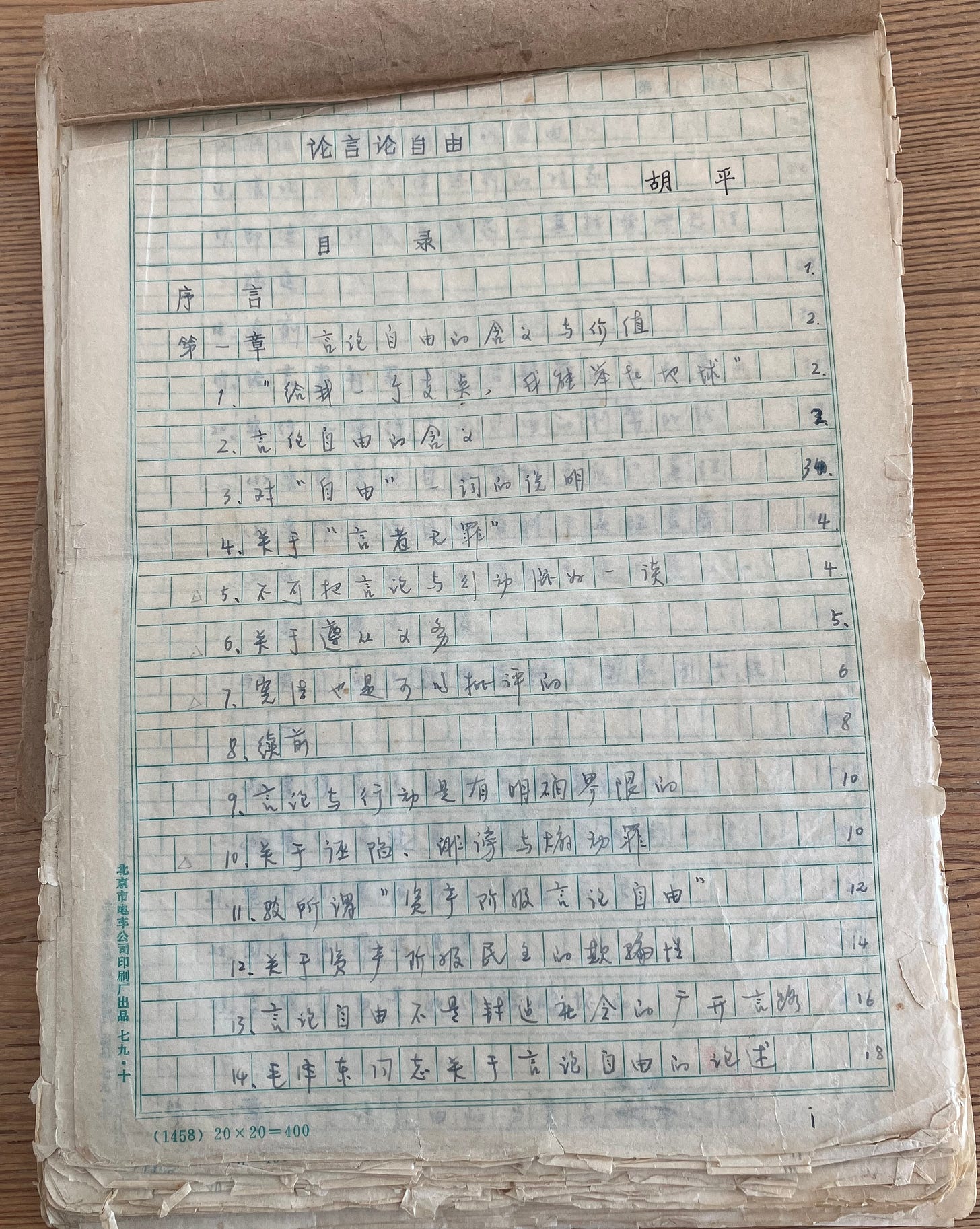

《论言论自由》一文最初于1979年由中国地下刊物《沃土》发表。作者胡平在1980年11月北京大学竞选人民代表期间,将该文抄成大字报张贴,并油印作为竞选文件。这场竞选是1980年代中国校园民主运动重要的一部分,《论言论自由》一文也得以广泛流传。此后由香港《七十年代》杂志(后来的《九十年代》)在1981年第3、4、5、6期连载。1986年,这篇5万多字的长文,第一次以铅印形式在大陆公诸于世,刊登在武汉的《青年论坛》1986年7月号和9月号上。其后,北京的三联、广州的花城和湖南出版社都曾计划出版单行本,但因反自由化运动兴起而未能实现。

《论言论自由》以启蒙性的语言阐释了言论自由的意义,反驳了人们对言论自由的误解和曲解,并提出了在中国实现言论自由的途径。

受访者胡平简介:

1947年生于北京。文革时在自办小报上转载遇罗克文章,1969年在四川下乡成为知青。1978年考取北京大学哲学系,并获硕士学位。1979年投入北京民主墙运动,1980年参加海淀区人大代表选举,并当选。1987年赴美国哈佛大学攻读博士。先后在《中国之春》和《北京之春》杂志社担任主编。现为《北京之春》杂志荣誉主编、中国人权执行理事等。

胡平的其它著作包括《中国民运反思》、《人的驯化、躲避与反叛》、《犬儒病》、《毛泽东为什么发动文化大革命》、《新冠肺炎浩劫——一场本来完全可以避免的大灾难》等。现居美国纽约。

以下访谈内容经过编辑。

档案馆:最初写《论言论自由》这篇长文的时候,您和我们的许多读者一样,还是一名学生。您当时是怎样到北京大学读哲学系研究生的?

胡平:文革时期作为下乡知青,我对书和知识非常饥渴,但是能接触到的书又非常少。那时经常是知道谁那里有本书,就老远跑去读。有时候能借回家看,有时候不能借,就只能在别人家熬夜看完,有时做点笔记。当时的笔记,现在我还有好几本。

我经常说,我们这一代人是很特殊的一代知识分子。改造我们的时候,就强调我们是知识分子,尽管有的人跟习近平一样,初中都没读完。但在安排我们生计的时候,从来不会说我们是有知识的,从来不想着发挥我们的知识特长。

我们在文革的时候读书,可以说是非常纯洁的,就是为了了解世界,满足求知欲,不是为了升学,因为那时没有大学可以考,更没有职称或是什么对口的工作。

当时了解西方的思想,能读到的书很少。一些西方思想的只言片语会出现在翻译过来的苏联教科书里,供批判来用。它不可能大段引用,否则就把论据全部展现出来了。所以我就要去“脑补”,把支离破碎的线索拼凑起来,顺着仅有的提示去思考:这些外界的思想到底是什么?

考北大前,我们都不知道研究生是怎么回事儿,因为太多年都没有这个学位,身边也没有人是研究生。我考研究生的时候,决定考哲学,因为哲学的面比较宽。哲学能够满足我那种什么都想知道的兴趣。高考的时候我在当临时工,想着能念上书本身就已经非常好了,去哪里都行。当时找差一点的学校考取的可能性更大,但是找了半天只有去北大能学西方哲学,“迫不得已”才报北大。

档案馆:请您谈谈《论言论自由》的写作背景。

胡平:《论言论自由》的第一稿写于1975年,文革后期。文革那种全面的压制,可谓物极必反——不只是像我们这些所谓“黑五类”,别人也都一样,包括共产党的官员,也都受了很多迫害。那样一种普遍压制下的绝望,造就了新的希望。

毛时代的那种压制,比西方中世纪的政教合一还要彻底、全面。你吃什么、穿什么,都要给你上纲上线。你私下说个话,写个信,都可能构成罪状。这种压制是全面性的,而一般的专制都不会将这种逻辑演绎到极致。

所以说,毛时代之后的那种状况在中国历史上是很少有的。其实世界很多地方的自由主义和自由概念都是在这种背景之下诞生的。对自由的压制走得很极端,才能迫使整个民族、整个国家产生这种强烈的对自由的渴求。

档案馆:中国的这种渴求,与其他地方如何比较?

胡平:这种对自由的渴求,八十年代在中国、苏联和东欧都是自发产生的。全面的压迫,造成了一种反弹,这是当时所有共产国家搞改革的基本动力。外部的影响是第二位的。有的人说,中国要自由化、民主化,需要中产阶级,需要市场经济。但是,所有共产国家成功推动政治改革,最初都没有中产阶级,也没有市场经济,这些都是后来才有的。还有人说,基督教对政治改革是必不可少的,但是当年的蒙古这些都没有,也没有基督教,可是说转就转了,而且进行得很和平,很顺利。所以说,对自由的渴望,是由一种无孔不入的压迫造成的。这一点,我觉得是特别要向现在的年轻人讲清楚的。

八十年代,思想能广泛传播,是因为人们有共同的集体经验,这些经验构成了自由理念生长的最佳社会基础。六四之前,从七十年代到八十年之间,当局也不停地反自由化,封杀民主墙,反“精神污染”,但是每次都是虎头蛇尾,都是是雷声大雨点小。而每次那种民间的、知识界的自由化力量都是稍微退一点,马上就反弹过来,而且比前一次来的声势更大。

档案馆:但是这种状况在八九后就改变了,这意味着什么?

胡平:如果八九不是失败得那么惨,就算被打压一下,抗议者退回去了,过两天又可以卷土重来嘛。可是六四的失败太惨了,三十几年都翻不了身,于是把文革——我们这个民族最沉重而又最宝贵的一次经验——消耗掉了。

当时文革后北大刚入学的学生,特别是比较年轻的学生,学过的教科书都是八股味十足的,都是很封闭、很保守的。很多人在我们选举活动之前,脑子里还一堆官方意识形态的教条,但是几场竞选讲演下来,他们的观点完全就变了。这是因为他们是有接受基础的,他们毕竟也有同样的经验,要么听过自己父辈那些讲述,要么自己多少有一些感受。只要唤起他们的共同经验,唤起他们的共同感受。然后把这种共同的经验、共同的感受,深化成一些理念,大家好像一夜之间就成了自由主义者。

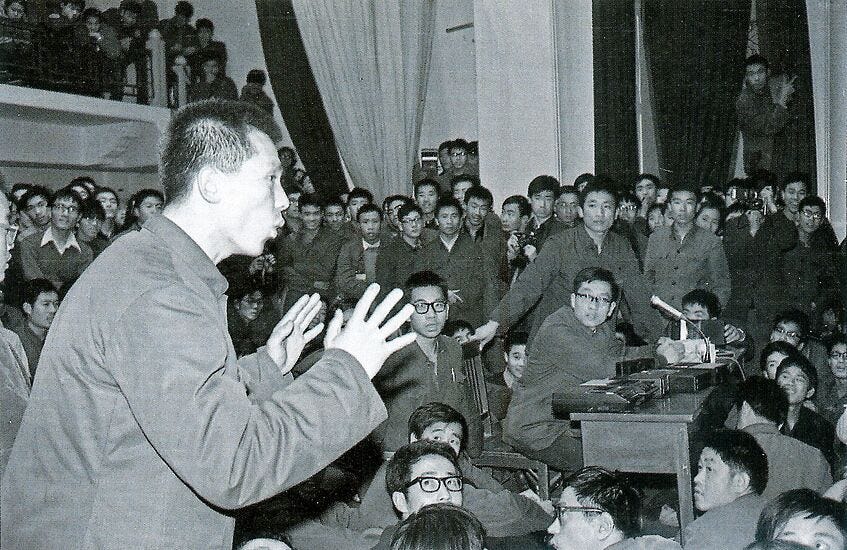

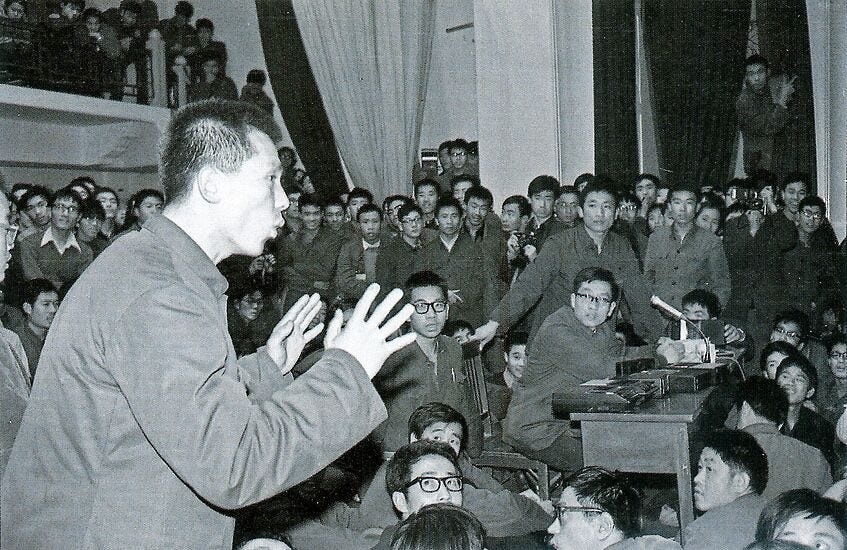

1980年的北大选举:更多是为了发声与传播民主理念

档案馆:请给大家讲讲当时的北京大学人民代表选举。《论言论自由》也是借那次选举而第一次被大量印刷并广泛传播的。

胡平:那次选举算是“四人帮”垮台后第一次选人民代表。文革前也有选举,因为理论上中国的宪法也承认各级人民代表和官员都要选举产生。但是以前都是所谓“等额选举”,连可供选择的候选人都没有,再加上压制不同政见,没有任何自由辩论的机会,所以选举就沦为形式,完全失去了选举的意义。

但是到了我们那次选举的时候,很多人就已经觉得,应该来点真选举。那时,全国人大公布了新的选举法,有的官方媒体都发文章主张竞选,可以毛遂自荐。

那一次县区级代表选举,全国不是同步进行的,有先有后。全国各地,北京是最后的。而北京几个区里,北大所在的海淀区,高校云集,也是最后的。我想当局肯定有这个考虑,就怕把北京放前头,海淀区放前头,担心北京的大学生会搞出什么新模式带动全国。

档案馆:当时这个区代表的选举意义何在?区代表的权力有多大?

胡平:区代表权限很小,只过问区里的事情。北京海淀区大部分单位是中央单位,区代表根本管不着的。所以区代表处理的,全是鸡毛蒜皮的事,没人会感兴趣的。人们感兴趣的当然都是宏观的问题。所以北大参选的同学,贴出来的竞选宣言,只谈天下大事,完全不管是在选区代表,当时就有人说这不像是选举区人民代表,这好像是选国会议员、选总理呐。事实上,同学们都把这次选举当成一种发声的机会,尽管区代表的选举,本身几乎毫无意义。

档案馆:所以,选举更多的是一种发声的机会?

胡平:对。因为这是一个传播理念的机会,所以大家参与的热情都非常高。竞选的那一个月,有很多讲演会、辩论会,学生在食堂里、回到宿舍里谈论的话题,都是选举,非常热闹。尽管大家都没有任何选举的经验,也没受过任何这方面的教育或训练,大家都无师自通,有的学生成立了选举观察,报道关于竞选的各种消息,有的发问卷民意调查,有的还定期更新。这种自办媒体,大概有四五家。在这种气氛里,那次选举把当时中国青年一代想的什么、追求什么、赞成什么、反对什么,非常清楚地表达出来了。

之前民主墙的时候,因为毕竟直接参与的人少,很多人只是当观众去看一看。但是选举不一样,因为一个社区里所有的人都参与。如果一个事情得到一万个人的关注,但这一万人是分散在各地的,那就构不成力量。如果这一万人聚集在一个地方,而这个地方又很重要,那就成为一件了不起的事了。北大的位置很重要,所以那次竞选的影响力才那么大。如果是别的边远的不知名的大学,你发表那些言论,可能谁都没听见,就公安局听见了。所以,北大竞选的象征意义很强,发挥了其他学校都起不到的作用。

档案馆:当选之后发生了什么?

胡平:可以说没发生什么。当代表,就是一年开一次会,所以说最重要的意义是竞选过程本身。当时有同学很热心,感到意犹未尽,要竞选运动中的活跃分子串联起来。不过我觉得应该见好就收,竞选这次就先到这吧,再继续搞下去恐怕会招来麻烦。

选举时我的想法是,一定要选上,否则官方宣传就可以说,有一小部分同学提出资产阶级思想,但是被大多数的同学拒绝,诸如此类。如果我们选上了,当局就没话可说了。

我思考言论自由问题的基本考虑,一是要在你共产党的眼皮底下向你挑战,二是要打到你的痛处,三是一定要让你吃不了我。我认为我们需要树立一个榜样,找到一种做法,探索一条路,又能打到对方要害,同时能保护自身的安全。让大家觉得我们就可以这么做的。而且做了这种东西风险很小,我们都承受得了,这样大家才会跟进。

民运的成功必须要靠大家来参与,必须要让具有一般知识的人都能领会你的道理,让具有一般勇气的人都能去参与。如果只有英雄虎胆的人才能参与,那你注定是孤军奋战,不可能成功。我们已经有很多烈士了,我们不是要牺牲,我们是要赢,我们一定要追求成功。

言论自由或可作为当下人们反抗的最大公约数

档案馆:所以您认为,提倡言论自由是一种低风险的反抗方式?

胡平:是的。哈维尔说,要“生活在真实中”,人们也常说要“讲真话”,但我以为,在暴政高压下,要求大家都讲真话是不现实的。对争取自由民主而言,我们不需要人人都勇敢,我们只需要大家都有权利的概念,有言论自由的概念。争取言论自由,并不要求每个人都勇敢地讲出自己的全部观点,它只要求,每当有人因为言论而遭到迫害的时候,我们坚决维护他的言论自由权利。

刘晓波被判刑后,崔卫平曾打电话给朋友们,很多人表示不赞同刘晓波的观点,但认为刘晓波不该因为言论而治罪。这就够了。这不正是伏尔泰“我不同意你的说法,但我誓死捍卫你说话的权利”的名言吗?你先表明不赞成其观点,你的风险就很小,当局就无法整治你。但是你坚决地维护了言论自由的权利。

档案馆:这种观念在毛时代存在吗?

胡平:过去,毛时代,国人就没有言论自由这个概念。文革期间那么多人因为言论被迫害,却没有人将其视为言论自由问题。那时候,大家都只是在争论《海瑞罢官》到底是不是反党反社会主义,是思想认识问题还是动机立场问题,是学术问题还是政治问题。没有人提出,这是一个言论自由的问题,只要是言论问题就不应该治罪。

我写《论言论自由》,就是想把言论自由的正面反面能说的都说到,让反对言论自由的人无法反驳,让更多的中国人理解和支持言论自由。

言论自由可以作为最大公约数,最大多数人都能接受。共产党也很难拒绝言论自由。有些人担心中国有了民主会天下大乱,有些人说中国有这样那样的问题还不能实行民主,但是要说言论自由,就没什么人反对了。要说中国连言论自由都不可以,那实在说不过去。

现在人们谈论中国,会把争论聚焦在具体问题上,比如经济好不好,老百姓生活有没有改善。说法各异,但谈到言论自由,谈到最基本的第一权利时,那些为中国现状辩护的人,也无法否认当下中国缺乏言论自由的事实,也很难否认中国应该有言论自由。

档案馆:《论言论自由》将言论自由称为能够改变世界的“阿基米德支点”。您能否详细阐述这一观点?

胡平:我把言论自由比作阿基米德支点,还比作极权专制的阿基里斯之踵,比作改变极权专制的突破口,是说从这个问题入手,风险最小,共识最大,而且一旦取得进展,一旦有了言论自由,其他问题就自然改变了。

前面我讲过,例如选举,本来中国的宪法也规定了选举,但以前的选举之所以沦为假选举,说到底就是没有言论自由。只要有了言论自由,宪法就被激活了,假选举就变成真选举。你看苏联东欧,有了言论自由,取消了以言治罪,马上就民主转型了。

档案馆:那么,您觉得现在中国人对言论自由的呼声为何还不够强烈?

胡平:现在的中国与八十年代很不一样。那时候,一般人对言论自由的含义不了解,但是有朦胧的集体经验和潜在的强烈的渴求。现在,了解言论自由的含义的人已经很多了,但是对言论自由的向往和追求比当年减少了。

档案馆:另一方面,是不是集体行动也变得困难了?以及当局现在处理言论的方式也更隐蔽了,比如直接删帖,而不是正面交锋?

胡平:是的,集体行动变得更困难了。另外,当局压制言论的手法也有改变。过去要以言论治罪,总要给你给出一个意识形态的理由,总要有个说法。现在就是直接出手压制,就是赤裸裸的暴力专政,不再需要任何说法。起初,互联网的普及大大地帮助了人们扩展言论空间,现在当局在控制的技术上有了很大的改进,动不动就删帖封号。当然,主要还是靠抓人,还是靠恐惧。

今天的中国人需要重建非暴力抗争的信心

档案馆:您对未来中国人争取言论自由和基本权利怎么看?

胡平:当年在思考言论自由的时候,我痛感,我们的前辈为自由民主奋斗了一百多年,也曾经取得过很多成就,可是到我们这里,一切都荡然无存,连一个独立发声的平台都没有。我想,无论如何,我们这一代应该做的好一点,至少要为后人留下言论自由。可是几十年过去了,曾经一度,我们也取得过不少成就,可是今天都失去了。今天中国的状况比我们当时还要糟糕。现在谈到言论自由,我感到非常沉重。

我常说,六四改变了中国,也改变了世界。今天世界对民主最大的挑战就来自中国。如果1989年中国能跨过那道关卡,实现民主转型,今天的世界将完全不同。八九民运的惨痛失败,让很多人失去了信心,于是就放弃了抗争。现在,很多人,中国人也好,外国人也罢,在分析预测未来中国政局的时候,都不把民间力量,都不把像八九民运一类的大规模的民间抗争当作变量当作要素了。这些年来,关于中共高层内斗的传言此起彼伏,其实反映了很多人对民间抗争不抱期待,所以只好盼望着宫廷政变了。

档案馆:这样看来,民主在中国实现,还有希望吗?

胡平:有人问我,中国离民主还有多少年?我说你这话不对。你这话是假定我们走在正确的道路上,只是目的地比较远,还需要再走一段时间。但要是这条道路就是错的呢?我们越走,不是越近,而是越走越远呢?自由民主离我们并不远,拐个弯就到了。我们需要的是改变方向。

八九民运是和平理性非暴力。八九民运的失败,很多人对和平理性非暴力失去信心,他们认为只有搞暴力。可是在今天中国的现实条件下,老百姓要搞暴力抗争、搞暴力革命没有可行性,总是沦为空话大话。

所以我认为,今天,我们必须重建非暴力抗争的信心。我们必须相信,即便面对中共这么残暴的政权,非暴力抗争任然是有空间,有可能的。过去我们的失败不是不可避免的,过去我们的失败也和我们自己的失策失误有关,我们完全能够克服这些失策失误。民间力量必须再出发。像言论自由是突破口这些理念,在今天仍然是有意义的。

档案馆:作为身在海外的中国人,现在能够做些什么?

胡平:我曾说过,铁幕里边有话没处说,铁幕外边说话没人听。如果中国是全封闭,像毛时代,里边根本听不见外边的声音,那么海外的异议就没有什么作用;如果中国全开放,海外能说的国内也可以说,海外的异议就没什么必要。正是在现在这种半开放半封闭的情况下,海外的异议声音和文字才既有可能又有必要。

既然海外的种种活动是一种间接作用,而非直接作用,那么最需要留下的就是文字和影像资料。本来,在八十年代,在江胡时代,国内出现了很多好书好文章,但是到了习近平时代都被删除被下架了。这样,海外的声音、海外的储存就变得更加重要,不可或缺。很多信息有超越时空价值,不会因时过境迁而失去意义。它们不但记录了历史,而且在未来还会大放光彩。

当然,只有启蒙性的文字,还不够。启蒙时代不在于有人讲,而在于有人听。我相信,未来中国必然还会有这样一个时代。

本期档案推荐:

胡平:《论言论自由》

“The yearning for freedom is born from pervasive oppression”—Hu Ping on his 1980s essay, “On Freedom of Speech”

Hu Ping’s essay “On Freedom of Speech” first appeared in 1979 in Wotu (Fertile Land), an underground Chinese publication. In November 1980, during his campaign for a People’s Congress representative seat at Peking University, Hu copied the essay onto big-character posters and distributed mimeographed copies as campaign materials. This election was a vital part of China’s campus democracy movement in the 1980s, and “On Freedom of Speech” circulated widely. It was then serialized in the Hong Kong magazine The Seventies (later The Nineties) in its March, April, May, and June issues of 1981. In 1986, this long essay, over 50,000 characters long, was first published in print in Mainland China, appearing in the July and September issues of Youth Forum in Wuhan. Following this, Sanlian Publishing House in Beijing, Huacheng Publishing House in Guangzhou, and Hunan Publishing House all planned to release it as a standalone book, but these plans were thwarted by the rise of the party’s anti-bourgeois liberalization movement in the late 1980s.

“On Freedom of Speech” explains the significance of free speech, rebutting common misunderstandings and distortions, and proposing methods for achieving it in China.

About Hu Ping

Born in Beijing in 1947, Hu Ping reprinted Yu Luoke’s articles in his self-published newsletter during the Cultural Revolution. In 1969, Hu was sent to the countryside in Sichuan as an “educated youth.” In 1978, he was admitted to Peking University’s Philosophy Department, where he earned his Master’s degree. He became involved in the Beijing Democracy Wall movement in 1979 and was elected to the Haidian District People’s Congress election in 1980. In 1987, he moved to Harvard University in the United States to pursue his doctorate. He has served as editor-in-chief for both China Spring and Beijing Spring magazines. Currently, he is the honorary editor-in-chief of Beijing Spring and an executive director of Human Rights in China, among other roles.

Hu Ping‘s other works include Reflections on China’s Democracy Movement, Man’s Domestication, Avoidance, and Rebellion, Cynical Disease, Why Mao Zedong Initiated the Cultural Revolution, Upside Down Justice - China’s Ethnic Problem and Democratic Transition, The COVID-19 Catastrophe - A Disaster That Could Have Been Completely Avoided. He currently lives in New York City.

The following interview content has been edited for conciseness and clarity.

China Unofficial Archives (“CUA”): When you first wrote “On Freedom of Speech,” like many of our readers, you were still a student. How did you come to study philosophy as a graduate student at Peking University at that time?

Hu Ping (“Hu”): During the Cultural Revolution, as an educated youth sent to the countryside, I was deeply hungry for books and knowledge, but my access to them was extremely limited. I often traveled long distances just to read a book if I knew someone had one. Sometimes I could borrow it to read at home, other times I couldn't, so I’d have to stay up all night at someone else’s house to finish it, occasionally taking notes. I still have several of those notebooks today.

I often say that our generation has a very unique group of intellectuals. When the authorities were “re-educating” us, they emphasized that we were intellectuals, even though some, like Xi Jinping, hadn’t even completed middle school. Yet, when arranging our livelihoods, they never acknowledged our knowledge or sought to utilize our intellectual strengths.

Our learning during the Cultural Revolution was remarkably pure: it was simply to understand the world and satisfy our thirst for knowledge. It wasn’t for testing because there were no universities to attend then, let alone job titles or relevant occupations.

At that time, there were very few books available for understanding Western thought. Fragments of Western ideas would appear in translated Soviet textbooks, presented as material for critique. They couldn’t quote large sections, as that would reveal too much of the argument. Therefore, I had to fill in the blanks, piecing together fragmented clues and following the scant hints to ponder: What exactly were these foreign ideas?

Before taking the Peking University entrance exam, none of us knew what a graduate program was. This degree hadn’t existed for many years, and no one we knew was a graduate student. When I decided to pursue graduate studies, I chose philosophy because its scope was broad. Philosophy could satisfy my interest in wanting to know everything. During the college entrance exam, I was a part-time worker, thinking that simply being able to study at all would be wonderful. At that time, it was easier to get into a less competitive school, but after searching for a long time, only Peking University offered Western philosophy. So I applied to Peking University.

CUA: What was the background of your essay, “On Freedom of Speech”?

Hu: The first draft of “On Freedom of Speech” was written in 1975, in the later years of the Cultural Revolution. The pervasive repression of the Cultural Revolution truly pushed things to an extreme—it wasn’t just those of us labeled as the “five black categories”; everyone, including Communist Party officials, suffered greatly. That kind of widespread despair under universal suppression generated new hope.

The suppression of the Mao era was even more thorough and all-encompassing than the church-state integration of the European Middle Ages. What you ate, what you wore—everything could be politicized. A private conversation or a letter could become a crime. This suppression was totalitarian, and typical authoritarian regimes don’t usually push this logic to its extreme.

Therefore, the situation after the Mao era was rarely seen in Chinese history. In fact, liberalism and the concept of freedom in many parts of the world were born under such circumstances. The suppression of freedom had to reach an extreme to compel an entire nation to develop such an intense longing for freedom.

CUA: How does this compare to other parts of the world?

Hu: This yearning for freedom emerged spontaneously in China, the Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe in the 1980s. Pervasive oppression led to a backlash, which was the fundamental driving force for reforms in all communist countries at the time. External influence was secondary. Some people argue that China needs a middle class and a market economy for liberalization and democratization. However, all communist countries that successfully reformed politically initially had neither a middle class nor a market economy; those emerged later. Others claim that Christianity is essential for political reform, but Mongolia at the time had none of these, nor Christianity, yet it transitioned quickly, peacefully, and smoothly. Therefore, the desire for freedom is caused by an omnipresent oppression. I believe this point is particularly important to explain clearly to young people today.

In the 1980s, ideas could spread widely because people shared common collective experiences, and these experiences formed the best social foundation for the growth of the concept of freedom. Before June Fourth, from the 1970s to the 1980s, the authorities continuously opposed liberalization, suppressed the Democracy Wall movement, and fought “spiritual pollution,” but each time, the authorities started strong and ended with little effect. And each time, the forces of liberalization among the populace and intellectuals would retreat slightly, only to rebound immediately with even greater momentum than before.

CUA: This seems to have changed after 1989. What happened?

Hu: If the democracy movement in 1989 hadn’t failed so miserably, even if they were suppressed and the protesters retreated, they could have made a comeback within a short time. But the failure of June Fourth was too devastating; for over thirty years, there has been no recovery. As a result, the Cultural Revolution—the most painful yet most valuable experience of our nation—was squandered.

Students who had just enrolled at Peking University after the Cultural Revolution, especially the younger ones, had only studied textbooks full of official dogma, which were very close-minded and conservative. Many of them had a lot of official ideological doctrines in their minds before our election activities, but after a few campaign speeches, their views completely changed. This is because they had a receptive foundation; after all, they also had similar experiences during the Cultural Revolution, either having heard stories from their parents’ generation or having some feelings of their own. When their common experiences and feelings were awakened, and then these common experiences and feelings were connected to specific ideas and concepts, it seemed that everyone became a liberal overnight.

The 1980 Peking University Election: Voicing and Spreading Democratic Ideals

CUA: Please tell us about Peking University’s People’s Congress election in 1980. “On Freedom of Speech” was also mass printed and widely disseminated for the first time during that election.

Hu: That election was the first People’s Congress election after the downfall of the Gang of Four. There were elections before the Cultural Revolution, because theoretically, China’s constitution also recognizes that representatives and officials at all levels should be elected. However, previously, they were all elections with one candidate, and there were not even alternative candidates, coupled with the suppression of dissent and lack of opportunity for free debate. Thus, elections became a mere formality that was completely meaningless.

But by the time of our election, many people already felt that there should be real elections. At that time, the National People’s Congress had promulgated a new election law, and some official media even published articles advocating for campaigning and self-nomination.

That election for county and district level representatives was not conducted simultaneously nationwide; some areas went first, others later. Beijing was the last to hold elections among all regions across the country. And within Beijing’s districts, Haidian District, where Peking University is located and many universities are concentrated, was the last. I believe the authorities certainly considered this, fearing that putting Beijing or Haidian District first would lead to Beijing’s university students creating a new model that would influence the entire country.

CUA: Do these elections matter? What power do the officials hold?

Hu: The power of a district representative is very limited; they only handle district-level matters. Most institutions in Beijing’s Haidian District are central government institutions, which district representatives simply had no power to manage. District representatives dealt only with trivial matters that no one would be interested in. But people are naturally interested in macro issues.

Therefore, the Peking University students participating in the election posted campaign declarations that only discussed national affairs, completely disregarding that they were electing district representatives. At the time, some people said it didn’t look like an election for district people’s representatives; it seemed like an election for members of parliament or a prime minister. In fact, students all treated this election as an opportunity to voice their opinions, even though the district representative election itself was almost meaningless.

CUA: So you saw the election as a way to spread ideas?

Hu: As it was an opportunity to spread ideas, everyone participated with great enthusiasm. During that month of campaigning, there were many speeches and debates. Topics of discussion among students in the cafeteria and back in their dorms were all about the election; it was very lively. Even though no one had had any electoral experience or had received any education or training about elections or political campaigns, everyone became self-taught.

Some students formed election observation groups, reporting various news about the campaign, some distributed questionnaires for public opinion surveys, and some even provided regular updates. There were probably four or five such self-published media outlets. In this atmosphere, that election very clearly expressed what the younger generation in China at the time was thinking, pursuing, supporting, and opposing.

Before the election, during the Democracy Wall movement, relatively few people were directly involved, and many were just spectators. But elections were different because everyone in a community could participate. If a matter receives attention from ten thousand people, but these ten thousand people are dispersed, it doesn’t add up to much power. If these ten thousand people gather in one place, and that place is important, then it becomes a remarkable event.

Peking University’s location was important, which is why that campaign had such a great impact. If it were some obscure university in a remote area, your published remarks might not have been heard by anyone except the police. Thus, the symbolic significance of the Peking University election was very strong, playing a unique role that no other school could replace.

CUA: What happened after you were elected?

Hu: One could say nothing happened. Being a representative meant attending a meeting once a year, so the most significant event was the campaign process itself. At the time, some classmates were very enthusiastic and felt they hadn’t done enough, wanting to connect the active participants of the campaign. However, I thought we should know when to quit and that the campaign should stop for now; continuing it might invite trouble.

My thought during the election was that we absolutely had to win, otherwise official propaganda could say that a small number of students proposed bourgeois ideas, but were rejected by the majority of students. If we won, the authorities would have nothing to say.

My basic considerations when thinking about freedom of speech were: first, to challenge the Communist Party authorities right under their noses; second, to hit them where it hurts; and third, to make sure they couldn’t hurt me. I believed we needed to set an example, find a method, and explore a path that could both strike at the opponent’s vital points and protect our own safety. We needed to make people feel that this is something we can do. And if the risks involved in doing such a thing were very small, and we could all bear them, then people would follow.

The success of a democracy movement must rely on broad participation. It must be able to make its principles comprehensible to people with ordinary knowledge, and to inspire participation from those with ordinary courage. If only heroes with extraordinary bravery can participate, then you are destined to fight alone and cannot succeed. We have already had many martyrs; we are not seeking sacrifice, we are seeking to win, and we must strive for success.

Freedom of Speech as the Greatest Common Denominator for Current Resistance

CUA: So you believe that advocating for freedom of speech is a low-risk form of resistance?

Hu: Yes. Vaclav Havel discussed “living in truth,” and people often talked about “speaking the truth,” but I believe that under the high pressure of tyranny, it is unrealistic to demand that everyone speaks the whole truth. For the cause of freedom and democracy, we don’t need everyone to be brave; we just need everyone to recognize rights and the freedom of speech. Fighting for freedom of speech doesn’t require everyone to courageously express all their views; it only requires that whenever someone is persecuted for their speech, we firmly uphold their right to freedom of speech.

After Liu Xiaobo was sentenced, Cui Weiping called friends, and many expressed disagreement with Liu Xiaobo’s views but believed he should not be punished for his speech. That’s enough. Isn’t that precisely Voltaire’s famous saying, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”? If you first state that you don’t agree with their views, your risk is very small, and the authorities cannot target you. But you are resolutely upholding the right to freedom of speech.

CUA: Did people seem to recognize such a right in the Mao era?

Hu: In the past, during the Mao era, Chinese people had no recognition of the freedom of speech. During the Cultural Revolution, so many people were persecuted for their words, yet no one viewed it as a freedom of speech issue. At that time, everyone was merely debating whether Hai Rui Dismissed from Office, which partly triggered the Cultural Revolution, was anti-Party and anti-socialist, whether it was a matter of ideological understanding or motive and stance, whether it was an academic or a political issue. No one suggested that this was a freedom of speech issue and that speech should not be criminalized.

I wrote “On Freedom of Speech” to comprehensively discuss both the positive and negative aspects of freedom of speech, so that those who opposed it could not refute it, and to enable more Chinese people to understand and support the freedom of speech.

Freedom of speech can serve as the greatest common denominator, acceptable to the largest number of people. It’s also difficult for the Communist Party to reject freedom of speech. Some people worry that China would descend into chaos with democracy, and some say that China has this or that problem and cannot implement democracy yet, but when it comes to freedom of speech, almost no one opposes it. To say that China cannot even have freedom of speech is simply indefensible.

Now, when people discuss China, they focus the debate on specific issues, such as whether the economy is good or whether people’s lives have improved. There are various opinions, but when it comes to freedom of speech, to the most basic primary right, even those who defend the current situation in China cannot deny the fact that China currently lacks freedom of speech, and it’s difficult for them to deny that China should have freedom of speech.

CUA: “On Freedom of Speech” refers to freedom of speech as the “Archimedean lever” that can move the world. Could you elaborate on this view?

Hu Ping: I liken freedom of speech to an Archimedean lever, and also to the Achilles’ heel of totalitarian autocracy, and to a point of breakthrough for changing totalitarian autocracy. This means that by starting with this issue, the risk is minimal, consensus is maximized, and once progress is made—once freedom of speech is achieved—other issues will naturally progress.

As I mentioned earlier, for example, elections will be one such issue. The Chinese constitution actually stipulated elections, but the reason past elections became fake elections was, fundamentally, the absence of freedom of speech. As long as there is freedom of speech, the constitution is activated, and fake elections become real elections. Look at the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe; once they had freedom of speech and stopped criminalizing speech, they immediately underwent democratic transitions.

CUA: Why do you think the call for freedom of speech among Chinese people is not strong enough today?

Hu: China today is very different from the 1980s. Back then, most people didn’t understand the meaning of freedom of speech, but they had a vague collective experience and a latent yet strong yearning. Now, many people understand the meaning of freedom of speech, but their yearning and pursuit of it have diminished compared to back then.

CUA: On the other hand, has collective action also become more difficult? And have the authorities’ methods of handling speech become more covert, such as directly deleting articles and online posts instead of engaging in direct confrontation?

Hu: Yes, collective action has become more difficult. In addition, the authorities’ methods of suppressing speech have also changed. In the past, to criminalize speech, they always had to provide an ideological reason; there always had to be a justification. Now, they directly suppress; it’s blatant autocracy no longer requiring any justification. Initially, the Internet greatly helped people expand their space for speech, but now the authorities have greatly improved their technology for control, deleting posts and blocking online accounts at will. Of course, the main method is still arresting people and relying on fear.

The Chinese People Need to Rebuild Confidence in Nonviolent Resistance

CUA: What are your thoughts on the future of Chinese people striving for freedom of speech and basic rights?

Hu: When I was contemplating freedom of speech back then, I felt deeply that our predecessors had struggled for freedom and democracy for over a hundred years, and had attained many accomplishments, yet by the time it reached us, everything was gone, and not even an independent platform for voicing opinions remained. I thought that, no matter what, our generation should do better and at least gain freedom of speech for future generations.

But decades have passed, and at one point, we had considerable achievements, but today they seem all lost. The situation in China today is even worse than it was for us back then. When I talk about freedom of speech now, my heart is very heavy.

I often say that June Fourth changed China, and it also changed the world. Today, the biggest challenge to democracy comes from China. If China had crossed that threshold in 1989 and achieved a democratic transition, the world today would be completely different. The tragic failure of the 1989 democracy movement caused many people to lose confidence and thus give up resistance. Now, many people, Chinese and foreigners alike, when analyzing and predicting the future political situation in China, no longer consider popular forces, nor large-scale popular resistance like the 1989 democracy movement, as key variables or factors. In recent years, rumors of infighting among the top Communist Party leadership have been rampant, which actually reflects that many people have no expectations for popular resistance, and therefore can only hope for a palace coup.

CUA: Does this mean that democracy is impossible?

Hu: People often ask me, “How many more years will pass until China achieves democracy?” I tell them, “That’s not the right question.” Your question assumes we are on the correct path, and the destination is just far away, requiring more time to walk. But what if this path is wrong? The more we walk, are we not getting closer, but instead getting farther away? Freedom and democracy are not far from us; they are just around the corner. What we need is to change direction.

The 1989 democracy movement was peaceful, rational, and nonviolent. The failure of the 1989 democracy movement caused many to lose faith in peaceful, rational, nonviolent approaches, believing that only violence would work. However, under China’s current circumstances, it is not feasible for ordinary people to engage in forceful resistance or violent revolution; it always amounts to empty talk.

Therefore, I believe that today, we must rebuild confidence in nonviolent resistance. We must believe that even when facing such a brutal regime as the Chinese Communist Party, there is still space and possibility for nonviolent resistance. Our past failures were not inevitable; our past failures were also related to our own missteps and errors, and we are fully capable of overcoming these missteps and errors. Popular forces must restart. Concepts like freedom of speech as a point of breakthrough are still meaningful today.

CUA: What can Chinese people living overseas do now?

Hu: I once said that behind the iron curtain, there is no place to speak, and outside the iron curtain, there is no one who listens. If China were completely closed, like in the Mao era, where voices from outside couldn’t be heard at all, then overseas dissent would have little effect; if China were completely open, and what could be said overseas could also be said domestically, then overseas dissent would be unnecessary. It is precisely in this current semi-open, semi-closed situation that overseas dissenting voices and writings are both possible and necessary.

Since overseas activism has an indirect rather than direct effect, we must try to preserve written and visual materials. Originally, in the 1980s and during the Jiang-Hu era, many good books and articles appeared domestically, but during the Xi Jinping era, they have all been deleted or censored. Thus, overseas voices and overseas safekeeping become even more important and indispensable. Much information has value beyond its own era and will not lose its meaning with the passage of time. They not only record history but will also shine brightly in the future.

Of course, the texts of enlightenment alone are not enough. Any era of enlightenment is not about whether there are people speaking, but about whether there are people listening. I believe that such an era will definitely come again in China’s future.

Recommended archive:

“On Freedom of Speech” by Hu Ping

Thank you for your Substack on Freedom in unfree CCP China.

It is stories of courageous dissidents like Hu that need to get out to the public.

Keep up your good work for bringing more freedom to China.