生育率下降的另一个视角:当女性要求拿回身体的自主权

Demanding the Return of Bodily Autonomy: An Alternative Perspective on China’s Declining Birth Rate

作者:米米亚娜

By Mimiyana

The English translation follows below.

2025年,我实现了自己当母亲的心愿——在加拿大,以单身生育的身份,顺利地生下了女儿。前两天,当我和一位在中国的好友聊起今后的育儿计划——考虑送托儿所、幼儿园的时间安排时,我告诉她加拿大的托儿所资源紧张,排队几年是常态。她很惊讶:“国内的幼儿园都没生意。”她说,“巴不得你去。”

我们同时提到中国新出炉的生育率有多惨淡。1月19日,中国国家统计局发布的数据显示,2025年的出生人口仅792万,较2024年下降了162万。每千人出生人数降至5.63,为1949年中共执政以来的最低水平(按照官方数据,2025年的出生人口,低于三年大饥荒时期的年出生人口)。与此同时,死亡人口与老龄人口均持续上升。总人口连续四年下降,且老龄化进一步加深。

从2015年彻底结束“一孩政策”,2021年推行“三孩政策”,到2025年开始发放育儿补贴,十年来,中国政府尝试了包括延长产假、提供税率优惠、购房补贴、设置“生育友好岗”等各种生育支持措施,可谓使尽浑身解数,却依然没能挽救出生率下跌趋势。

1. 当结婚不再是生育的前提

不仅是中国大陆,香港、台湾的新生婴儿也再创新低。香港2020年有4.3万新生婴儿,2025年已跌至不足3.2万,6年间减少26.2%。台湾减幅更大,2020年有16.5万新生婴儿,但2025年已跌至不足10.8万,6年间减少34.7%。这两地连同韩国,长期占据全球最低生育率地区前三。

迫于人口危机的压力,原本儒家文化深厚的台湾,在2025年底推动了《人工生殖法》修法,提出将人工生殖适用范围从原本的“异性不孕夫妻”,扩大到单身女性与女同志配偶。一旦草案通过,台湾将成为华语世界唯一允许单身女性与女同志伴侣合法解冻并使用自己卵子的地区——此次修法意味着生育权第一次与婚姻制度正式脱钩。当结婚不再是生育的前提,不婚人士与多元家庭的生育意愿便能得到释放。

这个改变带来的意义,不仅仅是“多生孩子”这么简单。历史上,女性长期被父权家庭和父权国家体制当做资源、工具,以延续父系的血统、财产和权力——女性嫁入夫家才能获取生存保障,还要为家务和育儿承担毕生的免费劳动。“婚姻”作为支配女性生育力的关键制度,是父权社会的底层建构。当有一天,破除了婚姻强加的生育合法性审查,女性能完全掌握自主生育权,那将意味着,她能够真正地不为男性、不为家庭和家族、不为国家,而只是为了自己而生(或不生)。

2. 在加拿大感受到公共意识的进步

我和这位国内的朋友同龄,曾经是中学同学。我们年轻的时候都把重心放在了学业、事业、自我追求和游山玩水上,都是人到中年才有了生育意愿,也都积极寻求过辅助生殖技术,区别是她已婚,而我在加拿大得以顺利地完成单身生育。

作为单身女性,我在加拿大接受有关生育的医疗服务、政府机构的行政程序和福利发放方面没有遇到任何障碍,但更触动我的是这里公共意识的进步,相关从业者会有意识地使用“包容性语言”,将单身人士当成主流的一部分。有一次我去参加一个NGO组织的线上育儿课程,讲课的是一位产科护士。当她提到“partner”的时候,特意解释:partner是指“育儿搭子”,可能是你的丈夫、妻子、同性伴侣、朋友或者父母。这个细节让我印象深刻,因为她作为一个公共事业的代言人,不默认你在异性恋的婚姻关系中。

去年,我所在的不列颠哥伦比亚省投入了6800万加币的公共资金资助IVF疗程(俗称的“试管婴儿”),每个名额最多资助1万9千加币,异性夫妻、单身女性、同性伴侣或性别多元家庭均有资格申请。这是一次政策的“精准投放”,政府选择去推动那些已经具有强烈生育意愿的人。这也意味着,国家把生育从“私人责任”提高成“公共基础设施”的一部分。

3. “总有一天,我们将收回身体的自主权”

我也一直关注中国的单身生育权利。2019年,30岁的单身女性徐枣枣向首都医科大学附属北京妇产医院寻求冻卵服务,因单身遭拒绝后,她以侵犯“一般人格权”为由将医院告上了法庭。历时三年多的庭审后败诉,她随后提起上诉,最终在2024年8月终审维持原判。

一审败诉后,徐枣枣说:“总有一天我们将收回我们身体的主权。”

当时中国已经开始积极推行“三胎政策”,这让此案显得颇为讽刺——把低生育率上升为国家危机、倾其所有政策工具“催生”的社会,却拒绝把生育自主权赋予最有生育意愿的一部分人。

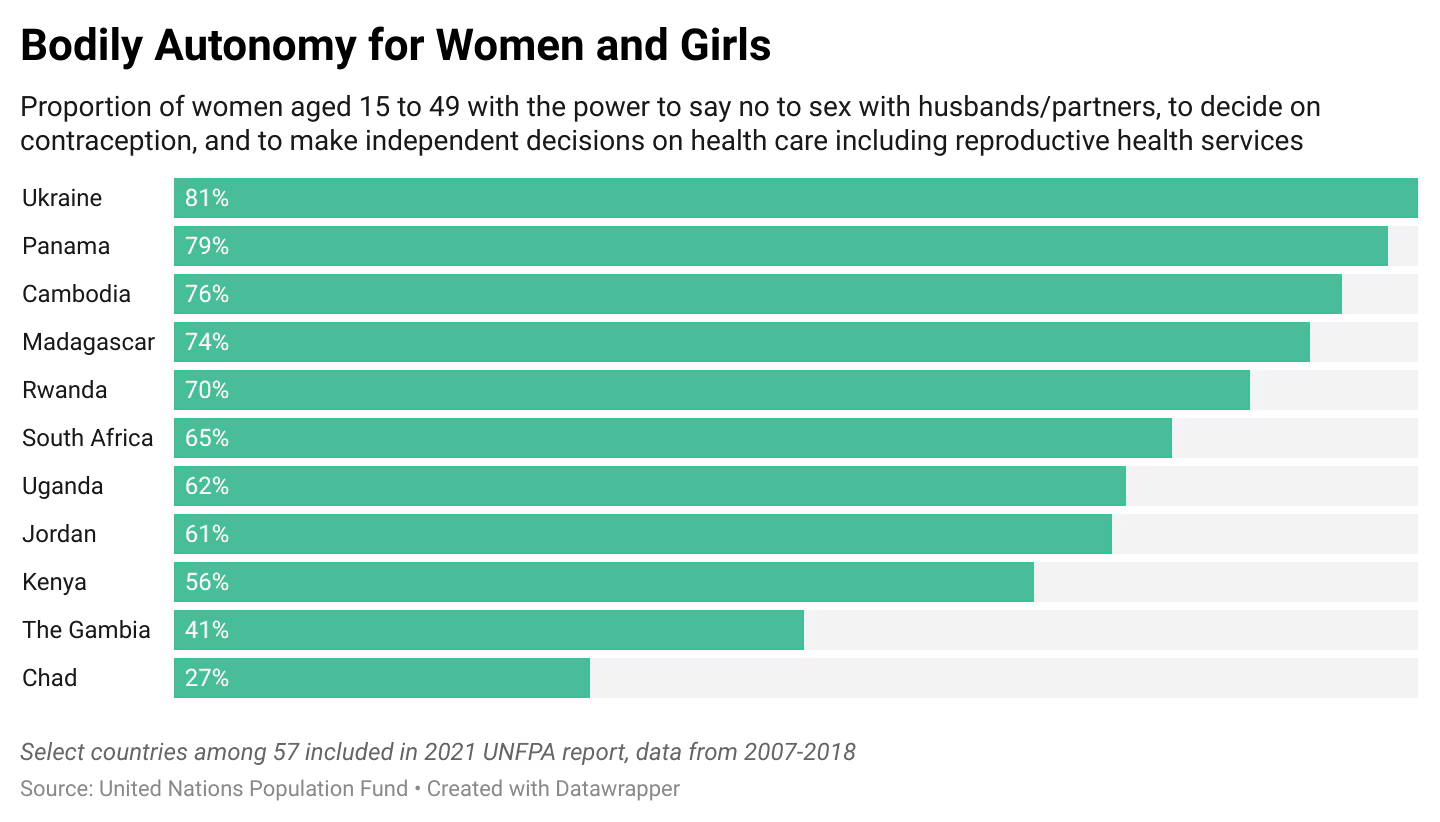

中国国家卫计委2003年修订的《人类辅助生殖技术规范》指出,“禁止给不符合国家人口和计划生育法规和条例规定的夫妇和单身妇女实施人类辅助生育技术。”可谓反映了问题的实质——女性的身体从来不是属于自己的,而是一种制度性资源,是国家人口治理的对象。

4. 中国的计划生育:女性承受了父权制最野蛮的一面

以计划生育为代表,中国对女性身体的制度化管理历史悠久。1949年建政之后初期,国家总体上鼓励生孩子,认为人口多就有劳动力,对国家建设有好处,但生育主要还是家庭的事;到了文革后期和1970年代,随着资源紧张和人口压力增加,政府开始提倡“晚婚、晚育、少生”,推广避孕措施,基层组织逐步介入,生育开始成为政府管理的对象;1980年代独生子女政策实施后,生育成为一种必须通过行政许可的行为,被全面严格管控,很多女性需要上环、定期妇检,有的还经历强制引产或结扎,无数女性为政策的畅行无阻承担了血肉代价;2015年以后人口危机凸显,国家从限制生育转向鼓励生育,全面放开二孩、三孩,社会和家庭的催婚、催生压力以及生育多胎的代价依然主要落在女性身上。

虽然中国在不同的阶段改变了生育管理的目标,但从未放开对女性的控制和施压,才会反复出现“想生的不能生,不想生的被迫生”的悲剧。女性的身体所承受的高度侵入和高度功能化,揭露了父权制最野蛮的一面。

如今,全球很多地方都出现生育率持续下降的现象。不过,对中国以及同样处于东亚社会的日本、韩国等来说,问题似乎更加严重。抛却政治、经济因素不谈,其实这本质上是一场全民(尤其是女性)的“生育罢工”。有充分的事实证明,在这些国家,政府即便祭出全方位的利好政策,或者直接“砸钱”,对扭转生育颓势的效果都微乎其微——东亚社会的深层社会结构和文化特质,严重地影响着这些地方的女性生育意愿。

就我对身边中产圈子的观察来说,很多人不但把自己的人生当成不断打怪升级的绩效项目,也把育儿当成自己的一个高压绩效项目。一旦生了小孩,就要把孩子培养成合格中产、社会精英。对孩子的期待不是成长为一个健康的人,而是要“跨越阶层”或者至少不“阶层下滑”。对精英化的养育的推崇,带来的不仅是高企的经济成本,更沉重的是一种心理成本——即必须确保孩子的人生“成功”,避免“失败”。而东亚文化对“成功”的定义极其狭窄,标准却又极其苛刻,容错率极低,导致无数人挤在同一个模板中卷生卷死,难以找到退出机制。

与此同时,在这些地方,育儿责任高度私人化,缺乏公共设施的支持。社会默认育儿是家庭劳动——更确切来说是女性应该承担的劳动。女性不但是“养育者”,还是一个“项目经理”,是孩子的直接和最终责任人,承担着几乎全部风险。

我妈说过一句让我印象深刻的话:“养好了是社会的,养坏了就是自己的。”回想起我的成长过程,她在每一个为我而做的决策上都是殚精竭虑,尽量推演出各种最坏的可能,以便能预先做好全部保险。妈妈一直是那个兜底的人,一直在防止我失败,我的失败也会被当成她的失败。这种长期的高压运行会异化人性——我常常觉得妈妈过度焦虑、负面、不快乐。

5. 年轻世代的女性第一次集体生育罢工

今天女性的受教育程度和经济参与度都前所未有,年轻世代的女性第一次集体看清了生育背后的勒索、母职背后的惩罚。“生育罢工”即是女性拒绝再为整个系统承担责任与代价——当我们无法在这个系统里获得作为“独立自主的人”的位置。女性以理性的利弊权衡、以身体与生命的自保直觉,拒绝再去延续和复制这个不可持续的系统,也宣判了系统的末日——它无法再依靠剥削无声的弱势群体来维持高绩效的运作。

写到这里,我不得不提出一个更深的疑问:生育率下降真的是一个需要解决的“问题”吗?如果没有资本主义要求的不断增长作为最高目标,人类为何要继续扩张?我们的生态环境、我们的星球、就连我们自己的人生,都已经不堪重负了,不是吗?

除了政治与社会的原因,生育率下降也可能是正常的生物对于环境压力的反应,也是生态系统的神秘“纠偏”机制。在动物行为学和生态学中,研究者早已发现,当种群过于拥挤、竞争过强、社会关系高度紧张时,一些动物会自动减少繁殖、放弃育幼,甚至在资源充足的情况下走向种群崩溃。因此,人类社会的低生育率,未必只是观念的变化,也可能是对高密度、高竞争、高压力环境的一种生物性适应。

如果这个社会无法改变(或者仅仅是“接受”)这种深层结构,却试图以“发钱”、“催生”的奖惩机制来干预人们的决策,无疑落入了典型的系统困境:试图以制造出了问题的逻辑去解决自己制造出的问题。

现代社会的很多制度,都建立在人口持续增长的基础上:养老金要靠源源不断的年轻人养活老人,房价和金融体系依赖对未来人口和收入增长的预期,老年人口比例上升也可能让政治更保守甚至倒退,国家之间的竞争也常常和人口规模、年轻人的劳动力和创新能力挂钩。

归根结底,“低生育率”更像是现有制度的危机,却不一定是人类本身的危机。人口变少难免遭遇阵痛,但长远来看,人类对能源的需求会下降,对土地和自然资源的压力也会减轻,更多生物的生存空间会得到恢复,碳排放也可能随之减少。人类社会也可以将重心从GDP增长转向如何提升个体的福祉。

以此为视角,我们需要重新定义“生育自主权”的意义:让人类跟随女性的生命直觉回归平衡。

女性掌握生育自主权最重要的一点,就是她可以选择不生——如果没有说“不”的权利,“自主”就无从谈起。具有主体性的女性能够决定如何在合适的时间、合适的环境、合适的状态中生育,或者当不合适的时候拒绝生育。换言之,当“母亲”能够作为一个“人”存在,她就能够为诞生的生命负责——能且只能通过为自己负责的方式。

如今的我,在选择了生育之后,深感成为母亲的命运偶然性。相比人生众多“可以选择”去做的事,生育确实很特别,却又没有那么特别。它和很多别的事一样,不同的人所体验到的可能天差地别,有人适应,就会有人不适应。一旦它不是“必须”的,它就必然会丧失用户。

我不知道人类社会要坚持尝试多少年才会承认旧体制已经无以为继。但我期待,当更多人把对生育议题的理解从“低生育率”转向“生育自主权”的时候,解法也自然会从“催生更多孩子”,变成“如何支持更多女性更好地做出关于生育的决策”。当然,这大概挽救不了低生育率,也许只能把生育率调整到它本来就应该降低的一个水平。

本期推荐档案:

Demanding the Return of Bodily Autonomy: An Alternative Perspective on China’s Declining Birth Rate

By Mimiyana

In 2025, I realized my wish of becoming a mother—in Canada. As a single woman giving birth, I successfully delivered my daughter. A few days ago, when I was talking with a close friend in China about future childcare plans—such as when to consider daycare and kindergarten—I told her that childcare resources in Canada are extremely tight, and that waiting in line for several years is the norm. She was very surprised: “Kindergartens back home don’t have any business at all,” she said. “They’d love for you to come.”

At the same time, we mentioned how dismal China’s newly released birth-rate figures are. On January 19, China’s National Bureau of Statistics released data showing that the number of births in 2025 was only 7.92 million, a decrease of 1.62 million compared to 2024. Births per thousand people fell to 5.63, the lowest level since the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949. According to official data, the number of births in 2025 is lower than the annual numbers during the years of the Great Famine in the Mao era. At the same time, both the number of deaths and the elderly population continued to rise. The total population has declined for four consecutive years, and population aging has further deepened.

From the complete termination of the “one-child policy” in 2015, to the introduction of the “three-child policy” in 2021, and to the beginning of childcare subsidies in 2025, over the past decade the Chinese government has tried every conceivable measure to support childbearing—including extending maternity leave, offering tax incentives, housing purchase subsidies, and setting up “childbirth-friendly job positions.” One could say it has exhausted all means, yet it has still failed to reverse the downward trend in birth rates. This is in line with declines in many other countries, and yet the decline in China—at a much lower per capita GDP than many other low-birth-rate countries—says much about its political system and embedded patriarchal systems.

1. When Marriage Is No Longer a Precondition for Childbearing

Besides mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other East Asian societies have also seen record lows in newborn numbers. Hong Kong had 43,000 newborns in 2020, but by 2025 this had fallen to fewer than 32,000, a reduction of 26.2 percent over six years. Taiwan’s decline is even greater: there were 165,000 newborns in 2020, but by 2025 the number had dropped to fewer than 108,000, a reduction of 34.7 percent over six years. Together with South Korea, these two places have long occupied the top three positions globally for lowest fertility rates.

Under pressure from the population crisis, Taiwan—despite its deep Confucian cultural roots—pushed forward amendments to the Artificial Reproduction Act at the end of 2025, proposing to expand the scope of assisted reproduction from its original target demographic—“infertile heterosexual married couples”—to include single women and lesbian couples. If the draft amendment passes, Taiwan will become the only place in the Chinese-speaking world that allows single women and lesbian partners to legally thaw and use their own eggs. This legislative change means that reproductive rights are formally decoupled from the institution of marriage for the first time. When marriage is no longer a prerequisite for childbearing, the reproductive intentions of unmarried individuals and diverse families can finally be realized.

The significance of this change goes far beyond simply having more children. Historically, women have long been treated by patriarchal families and patriarchal state systems as resources and tools, used to continue patrilineal bloodlines, property, and power. Only by marrying into a husband’s family could women obtain basic security for survival, while also bearing a lifetime of unpaid labor in housework and childrearing. Marriage, as the key institution controlling women’s reproductive capacity, is a foundational structure of patriarchal society. The day that the legitimacy screening imposed by marriage on reproduction is dismantled, and women can fully own their autonomous reproductive rights, it will mean that they are truly able to give birth (or not give birth) not for men, not for families or clans, and not for the state—but solely for themselves.

2. Experiencing the Advancement of Public Consciousness in Canada

My friend in China and I are the same age; we were classmates in secondary school. When we were young, both of us placed our focus on education, careers, self-realization, and traveling the world. It was only in middle age that we developed the desire to have children, and both of us actively sought assisted reproductive technologies. The difference is that she is married, while I was able to complete single motherhood smoothly in Canada.

As a single woman, I encountered no obstacles in Canada in terms of reproductive medical services, administrative procedures at government institutions, or the distribution of benefits. What moved me more deeply, however, was the advancement of public consciousness here. Relevant professionals consciously use inclusive language, treating single people as part of the mainstream. Once, I attended an online parenting course organized by an NGO, taught by an obstetric nurse. When she mentioned the word “partner,” she deliberately explained that “partner” refers to a “parenting partner,” which could be your husband, wife, same-sex partner, friend, or parent. This detail left a deep impression on me, because as a representative of a public service, she did not assume that people were in heterosexual marriages.

Last year, British Columbia invested CA$68 million of public funds to subsidize IVF treatments, with each recipient eligible for up to CA$19,000. Heterosexual couples, single women, same-sex couples, or gender-diverse families are all eligible to apply. This was a case of precision targeting in policy design: the government chose to support those who already have a strong desire to have children. It also means that the state has elevated reproduction from a private responsibility to part of public infrastructure.

3. “One Day, We Will Reclaim Sovereignty Over Our Bodies”

In 2019, a 30-year-old single woman, Xu Zaozao, sought egg-freezing services from Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital affiliated with Capital Medical University. After being refused because she was single, she sued the hospital on the grounds of infringement of her “general personality rights.” After more than three years of trial proceedings, she lost the case. She subsequently filed an appeal, and in August 2024 the final ruling upheld the original judgment.

After losing the first-instance trial, Xu Zaozao said: “One day, we will reclaim sovereignty over our bodies.”

At that time, China had already begun actively promoting the “three-child policy,” which made this case particularly ironic: a society that elevates low fertility to the level of a national crisis and deploys all policy tools to encourage births, yet refuses to grant reproductive autonomy to a segment of the population with the strongest desire to reproduce.

The Technical Standards for Human Assisted Reproductive Technology, revised by China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission in 2003, state that “it is prohibited to implement human assisted reproductive technologies for couples and single women who do not comply with national population and family planning laws and regulations.” This reflects the essence of the problem: women’s bodies have never belonged to themselves, but rather constitute a kind of institutional resource—an object of state population governance.

4. China’s Family Planning: Women Have Borne the Most Brutal Face of Patriarchy

China has a long history of institutionalized management of women’s bodies. In the early period after the founding of the state in 1949, the country generally encouraged childbirth, believing that a large population meant more labor and was beneficial to nation building, while reproduction remained primarily a family matter.

By the late Cultural Revolution and the 1970s, as resource constraints and population pressure increased, the government began advocating “late marriage, late childbirth, and fewer births,” promoting contraceptive measures. Grassroots organizations gradually became involved, and reproduction began to become an object of government management.

After the implementation of the one-child policy in the 1980s, childbirth became an act that required administrative approval and was comprehensively and strictly controlled. Many women were required to have IUDs inserted and undergo regular gynecological examinations; some even experienced forced abortions or sterilizations. Countless women paid a price in blood to ensure the smooth implementation of policy.

After 2015, as the population crisis became increasingly evident, the state shifted from restricting births to encouraging them, fully opening up second and third children. Yet the social and familial pressure to marry and give birth, as well as the cost of having multiple children, still primarily falls on women.

Although China has changed the objectives of population management at different stages, it has never loosened control over or pressure on women. This is why the tragedies of “those who want to give birth cannot, and those who do not want to give birth are forced to give birth” repeatedly occur. The high degree of bodily intrusion and extreme functionalization imposed on women’s bodies expose the most brutal face of patriarchy.

Today, many countries throughout the globe are seeing falling birth rates. However, China—and indeed the whole of East Asian society—has faced compounding challenges. In essence, what we are witnessing is a society-wide “birth strike” (by females). Ample evidence shows that even when governments roll out favorable policies, or even “throw money” at the problem, the effect on reversing fertility decline is minimal. The social structures and cultural characteristics of East Asian societies have influenced women’s willingness to bear children.

Based on my observations of the middle-class circles around me, many people not only treat their own lives as continuous performance projects of leveling up, but also treat childrearing as a high-pressure performance project. Once they have children, they must raise them to become qualified members of the middle class or social elites. Expectations for children are not about growing into healthy human beings, but about crossing class boundaries, or at least avoiding downward mobility.

The worship of elite-oriented parenting brings not only soaring economic costs, but also a heavier psychological burden—the need to ensure the “success” of a child’s life and avoid “failure.” East Asian culture defines “success” extremely narrowly, yet sets extraordinarily harsh standards with very low tolerance for error, forcing countless people to crowd into the same template and compete themselves to exhaustion, with no clear exit mechanism.

At the same time, in these places, childcare responsibilities are highly privatized and lack support from public infrastructure. Society defaults to childrearing as family labor—more precisely, labor that women should undertake. Women are not only caregivers, but also project managers, the direct and ultimate persons responsible for children, bearing almost all of the risk.

My mother once said something that left a deep impression on me: “If you raise children well, they belong to society; if you raise them badly, they belong to yourself.” Looking back on my own upbringing, I find that my mother was exhaustively cautious in every decision she made for me, trying to anticipate every worst-case scenario so she could prepare all possible safeguards in advance. My mother was always the one providing the final safety net, always preventing my failure, for my failure would also be regarded as her failure. This long-term operation under high pressure takes a toll on the well-being of mothers—I often feel that my mother was excessively anxious, negative, and unhappy.

5. The First Collective Birth Strike by Young Women

Today, the high levels of women’s education and economic participation are unprecedented. For the first time, a younger generation of women has collectively seen through the coercion behind reproduction and the punishment embedded in motherhood. A “birth strike” is precisely women’s refusal to continue bearing responsibility and costs for the entire system—when we cannot obtain a position as independent, autonomous persons within it. Through rational cost-benefit calculations and through bodily and life-preserving instincts, women refuse to continue sustaining and reproducing this unsustainable system, thereby pronouncing its end. It can no longer rely on exploiting silent and vulnerable groups to maintain high-performance operation.

At this point, I cannot avoid raising a deeper question: Is declining fertility really a “problem” that needs to be solved? If endless growth demanded by capitalism is no longer the highest goal, why must humanity continue to expand? Our ecological environment, our planet, and even our own lives are already overloaded—aren’t they?

Many modern institutions are built on the assumption of continuous population growth: pension systems rely on a steady influx of young people to support the elderly; housing prices and financial systems depend on expectations of future population and income growth; rising proportions of elderly populations may make politics more conservative or even regressive; and competition between states is often linked to population size, youthful labor forces, and innovative capacity.

Ultimately, low fertility looks more like a crisis of existing systems, rather than necessarily a crisis of humanity itself. Population decline inevitably brings growing pains, but in the long run, humanity’s demand for energy will decrease, pressure on land and natural resources will ease, more living space for other species will be restored, and carbon emissions may also decline. Human societies could shift their focus from GDP growth to improving individual well-being.

From this perspective, we need to redefine the meaning of reproductive autonomy: respecting women’s intuition about how to lead their lives and seeking a new state of balance.

The most important aspect of women possessing reproductive autonomy is that they can choose not to give birth—without the right to say “no,” autonomy does not begin to exist. Women can decide how to give birth appropriately or refuse to give birth when conditions are not ideal. In other words, only when the mother can exist as a person can she be responsible for the life she brings into being—by being responsible to herself.

As someone who has now chosen to give birth, I deeply feel the contingency of becoming a mother. Compared with the many things in life that one can choose to do, reproduction is indeed special, yet not that special. Like many other things, different people experience it in vastly different ways; some adapt, and others do not. Once it is no longer mandatory, it will inevitably lose “users.”

I do not know how many years human societies will continue to try before acknowledging that the old system can no longer be sustained. But I hope that when more people shift their understanding of reproductive issues from low fertility to reproductive autonomy, the solutions will naturally move from urging more births to how to support more women in making better reproductive decisions. Of course, this probably will not reverse low fertility. Perhaps it can only adjust fertility to the level at which it was always meant to decline.

Recommended archives:

Ai Xiaoming: Oral Interviews with Global Feminists

Chen Jian: Documenting the Reproductive Revolution in China, 1978-1991