重建中国独立思想者的家园——“发现中国民间档案”

A new home for independent Chinese thinkers—and a new publication, "Mining the Chinese Archives."

作者:张彦

By Ian Johnson

The English version of this newsletter follows the Chinese version below.

15 个月前,即 2023 年 12 月 11 日,我们成立了中国民间档案馆。作为一个非营利性机构,民间档案馆致力于收集被审查和压制的书籍、杂志、文章和影视资料,为中国的独立思想者们建造一个永久的家园。在这里,读者得以见到被掩盖的、不被允许存在的、却独立而坚韧地存在着的思想。

建立民间档案馆,探索、收集、组织、管理、策划、推出这些创作者和他们的作品——这是一项持续进行的项目。我们希望在官方话语里不被允许存在的作品能够得到读者的关注,也希望读者可以借此了解、认识、理解官方和主流以外的被打压、被审查的思想、创作、艺术、文学、影像——意即,历史与记忆。希望通过我们的持续努力,民间档案馆能给所有独立的思想和历史提供一个自由、不受审查的永久家园,并成为读者了解非官方叙事、建立独立思考的最全面的思想资源。

今天,我们很高兴向大家宣布,民间档案馆已完成全新升级,并增设了一系列新功能。您将看到更易使用的界面、更全面的中国独立思想家数据库、民间历史地图和全文检索——以下我们将详细介绍这些功能。

首先,请允许我介绍一下您正在阅读的内容:这一期简报既是我们关于网站升级的介绍,也是我们新设的题为“发现中国民间档案”的每周简报的发刊词。未来,我们将在每周简报中结合当下中国社会议题介绍中国民间历史书写、记录中值得关注的书籍、影视、艺术作品,以及它们的创作者,希望以此作为读者在当下的社会和历史语境里,探索、认识民间档案馆馆藏作品的桥梁和通道。我们目前已联系近十名作者,他们有些是长期记录中国的记者、写作者,有些是长期关注研究中国问题的学者,这些作者将在每期简报中聚焦我们的馆藏的档案,并将之置于当下中国的社会语境进行介绍和讨论。

我们将为读者介绍记录历史的创作者和他们的作品,但我们会重点聚焦当下的结构性问题,如一党专政、受限的言论和行动自由、女性受到的歧视、少数民族的二等公民待遇,以及中国周边地区的强制同化(尤其是西藏、新疆和香港)。我们也会关注中国农村问题,中国的农民是建设中国城市,生产出二十一世纪初中国经济奇迹,中国制造业的主要力量,但却在城乡制度下被当作低等公民对待至今。

自 1949 年中华人民共和国成立以来,这些问题一直存在,中国人也一直在讨论这些问题并进行反抗。理解历史,对理解当下是必不可缺的。但由于中国官方话语对民间历史的全面压制,我们很难对现在的社会问题有纵深全面的讨论和理解,甚至有些人会认为习近平统治下的社会问题是几年前才开始出现的。借由中国民间档案馆,我们希望读者可以了解前几代独立思想家的作品和人生,借用这些思想资源,去思考当下的问题。希望这些人——从毛时代独立思想的先驱,如遇罗克和林昭,到近年来勇敢行动的公民,如彭立发——的思想、行动和生活,可以让我们获得新的思考的资源、更多的能量、更多的行动的勇气和力量。

我们的作者队伍来自中国内外,并会不断变化。我会是其中之一,但不是主要的——因为我们在建设一个多元化的作者群体,有些是汉族,有些则是少数民族,有些是中国人,有些则在海外,有些来自中国腹地,有些来自边缘地区,这些作者有不同的关注面向,有对个人和个人所处的群体来说更紧迫的议题,而我们希望可以在新推出的栏目中,为我们的创作者们提供多样的选择和讨论的平台。

如果您选择订阅或继续订阅我们的简报,在未来,您将听到这些作者们的声音。他们将深入馆藏档案,帮助我们探索当下中国的重要社会问题。我们的简报旨在结合当下中国,介绍进行着独立思考和记录的作品以及这些作品背后及周围的人物和创作者。这些人物值得被了解、被记住,因为他们是 20 世纪和 21 世纪最重要的良知之声。

这次的网站升级将为读者提供一系列新功能,包括:

新的创作者数据库。在升级之前,民间档案馆只提供出版物和影视检索——您可以按主题、年代、形式或创作者分类浏览档案馆馆藏。现在,我们新建了“创作者”栏目,在这一栏目下,我们提供上百位中国独立作家和电影制作人的介绍,在未来,我们打算将其扩展到用艺术和音乐来独立思考和记录的人——我们统称他们为 “创作者”。我们希望将民间档案馆建造成最全面的中国独立思想家数据库。长期以来有种盛行的观点,即参与政治的独立活动者们仅限于中国大城市中的少数持不同政见者。我们的馆藏说明,这个观点并不准确:在中国的不同群体,不同地域,不论乡村或城市,体制内或体制外,都存在这样的人,他们保持着独立的思考,并用不同的方式参与建造更好的社会。

图书和杂志的全文检索功能。本次升级之前,读者如果要搜索某一主题相关的档案,只能通过我们已建立的标签进行,比如,有读者需要搜索与“文化大革命”相关的资料,只有当一本书或一部电影被标记在 “文化大革命 ”的类别中,它才会出现在“文化大革命”的搜索结果中。现在,您可以输入任意字段(如人名、地点或特定概念)检索全文(目前不是所有文档都支持全文检索),借助全文检索功能,读者还可以进行个性化的探索。例如,通过全文检索特定字段,找出某些术语(如 “女权主义 ”或 “法治”)的流行时间。

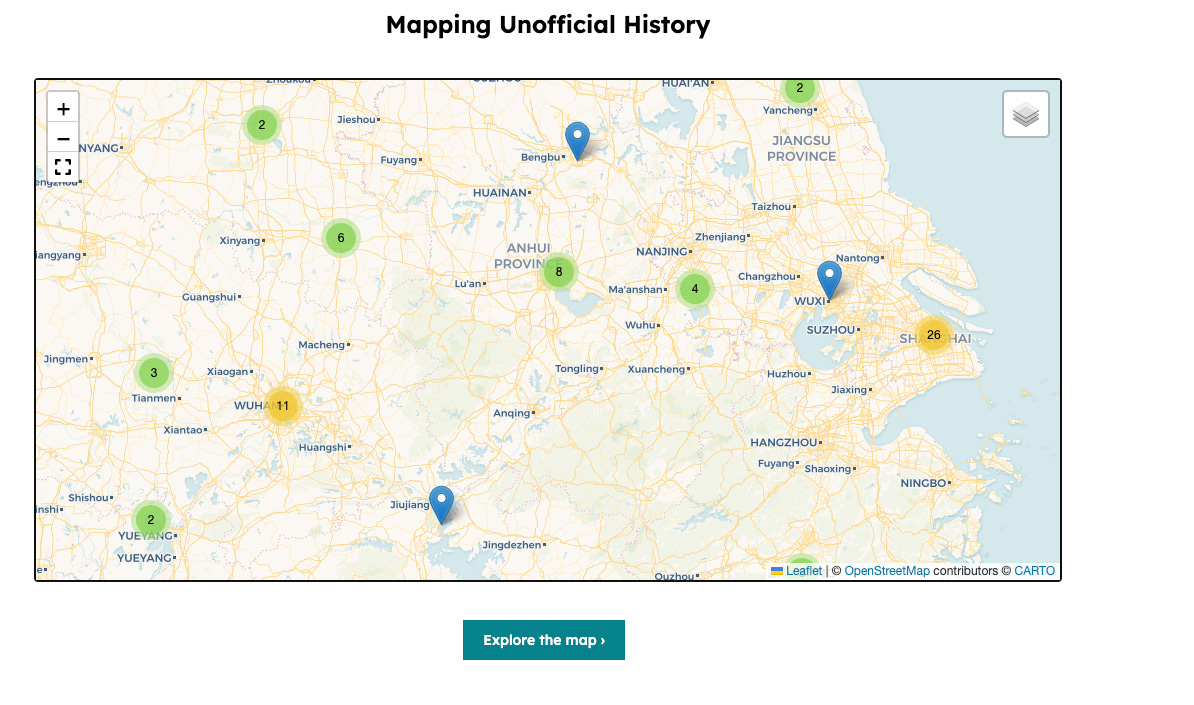

民间历史地图功能。您在主页和下拉菜单中可以看到,我们新增了民间历史地图。我们为档案条目添加了地点标签,例如某个创作者的出生地和死亡地,或某事件的起源地。读者可以点击地图上的标记,看看那里发生过什么,留下了哪些民间历史记录。我们目前仍在改进这一功能,现在我们已经完成标记几百个地点。

主题和年代页面功能更新。我们对档案馆馆藏的主题和年代标记进行了更新,现在您可以通过点击主题或年代,探索相关馆藏。今后,我们将提供这些主题和时代的定义——这些年代和主题分类本身是为中华人民共和国历史的参考系。

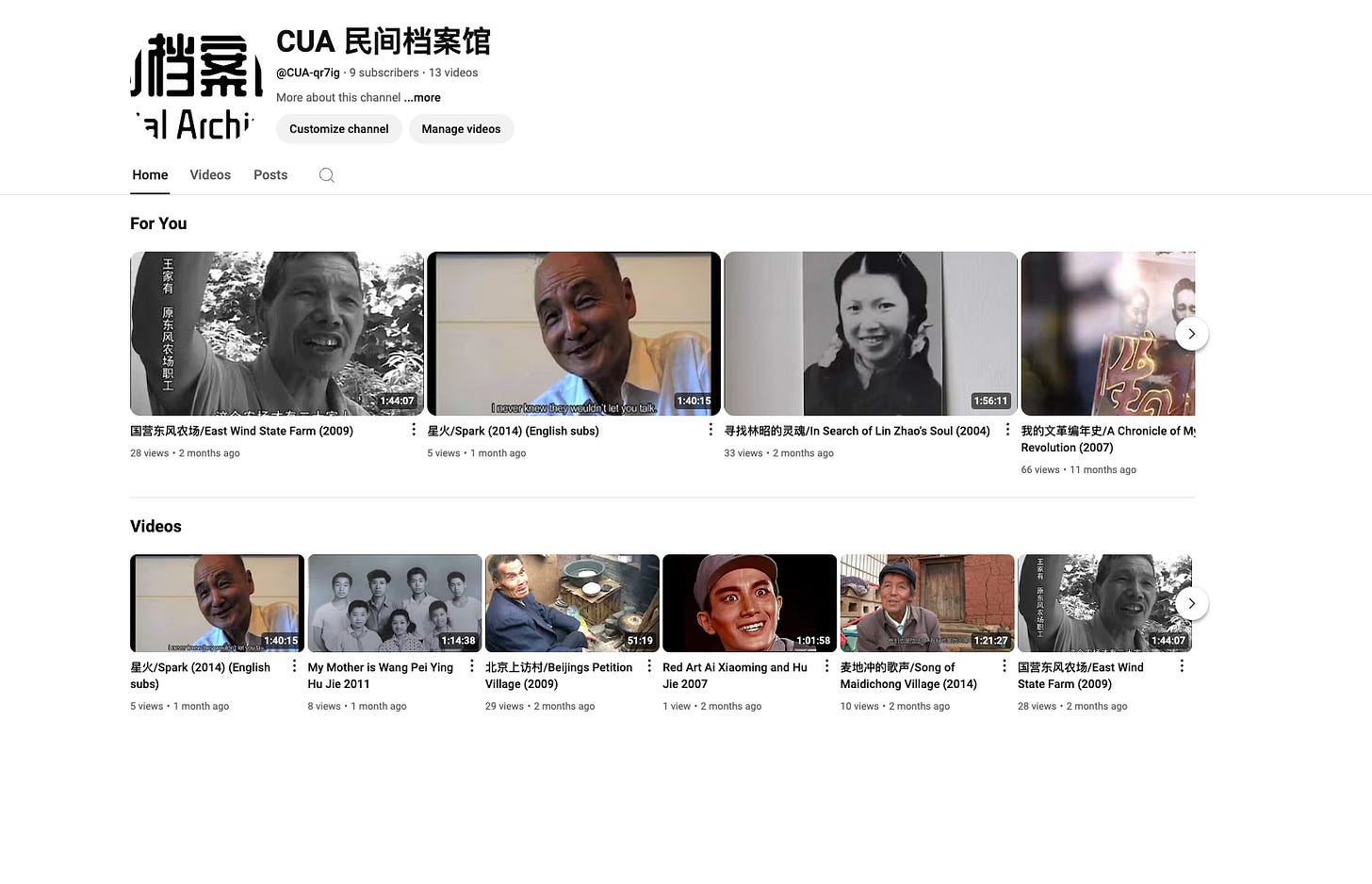

民间档案馆YouTube 频道建立。本次升级之前,我们通常会在档案馆中跟读者分享网上现有影像资料链接。可以预料,这种做法并不可靠,因为这些视频随时可能被主动或被迫删除下架。现在,我们已经创建我们自己的YouTube频道。我们目前上传了 13 部影片,但未来还会持续上传更多。这些影像及其记录的历史鲜为人知,但却是最为鲜活的记忆方式,虽然很多创作者们的姓名不为人知,但我们希望他们记录的历史能得到读者的关注,因为它们的存在难能可贵。

社交媒体定期更新。我们已经准备好在Twitter、Facebook 、Instagram 以及Bluesky和一些中国社交媒体上推广民间档案馆及其馆藏。我们还将推出 “历史上的今天 ”专题,定期推出每周简报以及新的馆藏。请点击关注我们的 YouTube、Twitter/X、Facebook、Instagram 和Bluesky账号。

我们刚开启还在进行中的工作包括:

增加香港、西藏和新疆的档案。

扩充创作者的数量,并提供更全面的创作者简介。

完善民间历史地图。

改进我们的全文检索功能,我们希望未来的搜索结果不仅能够显示馆藏名目,还可以直接标记到含该搜索项目的文本段落。

最后,我希望您可以点击进入我们的档案馆,尝试使用它,同时,我们非常期待收到您的反馈和建议。希望有更多的人发现民间档案馆,发现我们的馆藏,以及这里所容纳的历史和人。您可以直接发送反馈到 idj@minjian-danganguan.org。

谢谢,

张彦

A new home for independent Chinese thinkers—and a new publication, “Mining the Chinese Archives.”

By Ian Johnson

Fifteen months ago, on December 11, 2023, we launched the China Unofficial Archives as a non-profit dedicated to making available the works of independent Chinese thinkers: their books, magazines, articles, and documentary films. It has since grown to be the most comprehensive collection of Chinese books, magazines, and films available online to the general public.

Today, we are happy to announce a significant upgrade to the Archives with an array of new features, including better graphic interface, a comprehensive database of Chinese independent thinkers, mapping functions, and full-text searches—more on these features below.

First, let me introduce what you are now reading: a weekly newsletter in which we will introduce key books, films, artwork, as well as writers and directors—people we call “creators”—who have been publishing books and making films over the 75-year history of the People’s Republic of China.

We’ll have the occasional housekeeping email like this one, but most newsletters will be under the rubric of “Mining the Archives.” With a staff of half a dozen writers from inside and outside the People’s Republic, we’ll shine a spotlight in our archive to feature people—from last year to last century—who speak to today’s issues.

We will write about creators who have written books or made films about the early years of CCP rule, but our focus is firmly in the present; we aim to look at the structural problems that are relevant today. These unfortunately timeless issues include the problems of one-person rule, the lack of freedom of speech, the second-class treatment of women and ethnic minority groups, and, more broadly, the forced assimilation of peripheral regions, not only Tibet and Xinjiang, but also Hong Kong. And of course, we’ll look at China’s countryside, where farmers have never been able to own their most valuable asset: their land.

All of these issues have been challenges since the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949 and have been discussed and analyzed by Chinese people inside China from the very start. Unfortunately, few of them are known to people of our era (both Chinese and non-Chinese). This means that when analyzing China under Xi Jinping we tend to think that the pressing problems of today only started a few years ago. It can help us to understand what people of earlier years thought about these challenges.

Learning about earlier generations of independent thinkers isn’t just helpful in framing the issues of today; it is empowering and inspiring to see the thoughts, actions, and lives of these people, from the brave pioneers of the Mao era, such as Yu Luoke and Lin Zhao, to courageous citizens of recent years, such as Peng Lifa, whose cri de coeur against China’s political system inspired the White Paper Movement in late 2022.

Who will write these articles? We’ll have a revolving cast of writers, some inside and some outside China. I’ll be one of them, but only once in a while. We want a diverse group of writers, some ethnically Chinese, others from minority groups, some from the heart of the country and others from the peripheries, or the diaspora.

In the coming weeks, if you choose to stay subscribed, you can hear their voices as they delve into the archives to help us understand some of today’s social issues. Our newsletter aims to feature a wide array of works of independent thought and the people behind these ideas. Even if you are not following China closely, you should know who some of these people are because they are some of the most important voices of conscience in the 20th and 21st centuries.

With today’s upgrade, we have a series of new features, such as:

· A new database of creators. Before this upgrade, the archive had one database: of publications and films. You could search that database by theme, era, format, or creator. Now, we have added a unique, bilingual database of independent Chinese writers and filmmakers. Because we intend to expand this to include people who use art and music to express their independent thought, we simply call them “creators.” We have more than one hundred creator bios and are adding more regularly. To our knowledge, this is the most extensive database of independent Chinese thinkers. We hope it serves as a corrective to the mistaken idea that opposition to one-party rule is limited to a handful of dissidents in big Chinese cities. This database introduces to us a broad array of people, including those who are “inside the system” (tizhinei). It should give pause to simplistic visions of China as a place where critical thinking has been silenced. That has never been the case and still is not.

· Full-text searches of books and magazines. Before this upgrade, searches were only by tags, so only when a book or movie was tagged “Cultural Revolution” could it show up in a search. Now, you can choose “full text” and search an entire book. This is especially helpful for users searching for specific names, places, or concepts. Going forward, it will also allow users to conduct textual analysis of works, such as figuring out when certain terms (for example “feminism” or “rule of law”) became widespread.

· Mapping. As you can see on the homepage and from the drop-down menu, we now have a mapping function. We have been going through the hundreds of items in our archive and adding tags for locations, such as where a person was born and died, or where a campaign originated. The maps themselves are fun—you can zoom into a part of the country (or even the world; some tagged locations are outside China) and see what happened there. We’re still building this function out but already have several hundred locations tagged.

· Pages for Themes and Eras. The archive tags items by themes and eras, so in the past you could search by a theme (for example “rule of law”) but could not click on that theme and arrive at a new page that holds all these items. Now you can, which makes it easier to look up similar works. In the future, we will also provide definitions for these themes and eras, turning these pages into reference pages for the history of the People’s Republic.

· YouTube Channel. Before this upgrade, we linked to other channels that posted films on YouTube. Predictably, this has proven to be unreliable, as videos hosted by others could be removed at any time. Now, we will link videos in the Archives to our own channel, which you can access here. Currently we just have 13 movies up but have another 150 to add. Stay tuned!

· Social media. In the past, we had social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram but did not use them much. Our initial launch was always conceived of as a soft launch that would allow us to gather feedback and improve weak areas. Now that we have done so, we are ready to promote the site on these three platforms, as well as Bluesky, and Chinese social media. We will offer “on this day” features, and promote this newsletter as well as new additions to the archive, such as our growing YouTube offering. If this interests you, please click here for our social media accounts on YouTube, Twitter/X, Facebook, Instagram, and Bluesky.

In the future, we still have a lot of work to do, including:

Adding more information on regions further from the center, such as Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang.

Increasing the number of creators and improving the quality of each biography.

Increasing the number of geographical tags.

Improving our full-text search function so that hits don’t just show the publication but also an excerpt of the text with the searched-for item.

Finally, I’d like to ask you, dear reader, for constructive suggestions. Please feel free to send me an email with your views at idj@minjian-danganguan.org.

Thanks,

Ian Johnson