《烟雨任平生》中的高耀洁:为了真相在耄耋之年流亡,她晚年的一份心灵独白

Gao Yaojie Through Rain and Mist: The Late-Life Monologue of a Noble Soul in Exile

作者:彼黍

By Bi Shu

The English translation follows below.

1996年,当69岁的退休医生高耀洁在一次会诊中接触到一名诊断出艾滋病的农村妇女时,她并不知道,这将是改写她自己晚年命运的一个时刻——高耀洁从这位因输血而感染的妇女开始,追根溯源调查当地贫困农民因在血站输血感染艾滋病的真相。她持续数年的努力,向世人揭开了河南“血祸”真相,也间接阻断了这场灾难向更大范围的蔓延。

二十世纪90年代初,河南省政府为了借助卫生系统创造收入,一度号召全省各地农民卖血“脱贫致富”,大力发展“血浆经济”,并因此兴建了大量的血站。很多血站由私人承包,而这些私人血站,在采血前,不做乙肝以及艾滋病毒的检测,且让多人共用针头,而且存在将血液成分混合后再输回给卖血者的现象,结果导致艾滋病毒通过卖血和输血,在农村贫困人群中蔓延泛滥。

高耀洁并不是第一个发现这个现象的人。早在1993年,河南省卫生部门就已经发现艾滋病在卖血人员中传播流行。1995年,河南周口临床检验中心的负责人王淑平就开始调查这起丑闻并做出报告,但报告被官方压制,她本人也遭遇打压。1996年高耀洁开始对艾滋病疫情深入调查,并自己出资做防艾宣传活动。那之后,她顶住压力,不断发声,而这些声音经由当时正在兴起的中国媒体传播,并得到国际社会的关注,最终河南“血祸”被全世界知晓。2009年8月,年过八旬的高耀洁离开中国,前往美国并开始了流亡生涯。从那以后到她2023年12月在纽约曼哈顿去世,她再没有能重返她心念所系的故土。

在逃离中国政府的监视之后,高耀洁继续讲述中国艾滋疫情的真相。在她的晚年,她写下多部回忆录,包括《高洁的灵魂:高耀洁回忆录》、《高耀洁回忆与随想》、《高耀洁忆往昔》,都值得后人品读。她一生大部分的时间都在饱经忧患的二十世纪中国度过,生命中充满了磨难与波折——她出生于1927年,小时候缠过小脚,上的是私塾,也曾在战乱中逃亡。后来她做过几十年的妇科医生,在文革中饱受苦难。

她传奇的人生曾被广泛报道,在这些叙述中,她有着英雄的光环。在中国,在政治环境相对宽松的年代,她甚至被评为官方媒体中央电视台评委2003年“感动中国年度人物”,她也获得《南方周末》2003年度人物提名,这在今天是不可想象的。国际上,高耀洁曾于2001年获得全球卫生理事会颁发的“乔纳森·曼恩世界健康与人权奖”。2002年,她被《时代》周刊评为“亚洲英雄”。2007年,小行星38980被以“高耀洁”来命名。

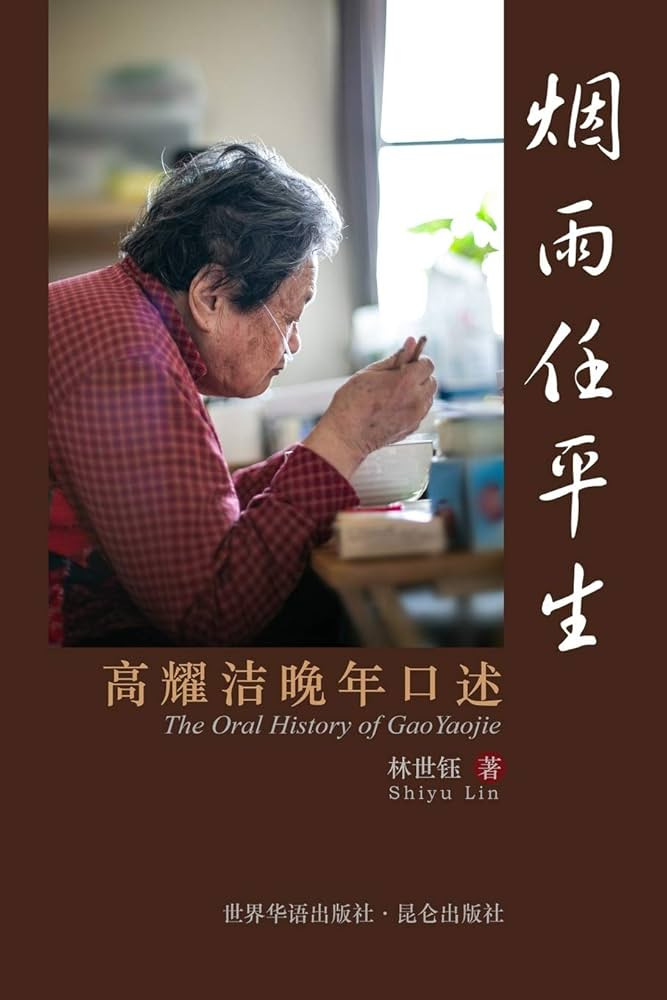

然而,高耀洁英雄般的存在,往往让人忽略她作为普通人的一面。她的另一本传记《烟雨任平生:高耀洁晚年口述》,则为后人理解高耀洁,提供了独特的视角和许多珍贵的材料,让她作为一个始终葆有良知与真诚的普通人的形象,跃然纸上。

本书作者林世钰曾在中国做过多年记者。她近年来旅居美国,对华人的海外生活经历有许多记录。为写下这本书,林世钰数十次访问高耀洁在纽约哥伦比亚大学附近的寓所,对她进行深入访谈。高耀洁曾在媒体采访中表示,这是“很普通的一本书”。但本书的口述史记录,对于采访者和受访者来说,其实十分不易。高耀洁晚年长期卧床,多次因重病住院,很多时候只能用笔答交谈。作者林世钰也是费尽心血,细致整理高耀洁的口述和笔录,将高耀洁的晚年境况和所思所想呈现在读者面前。

在踏上为艾滋病患者奔走的道路后,高耀洁亲眼目睹了艾滋患者的绝望,无数个家庭被病情摧毁,很多孩子因为父母患病双亡,成为了孤儿。她为此十分痛心,这也促使她要竭力去讲出真相。

对于高耀洁为揭开艾滋疫情真相进行的走访和对艾滋孤儿的照顾,《烟雨任平生》一书中有详细的回顾。不过在《烟雨任平生》一书发布后,高耀洁一如既往地表示:“我也没有做出啥了不起的事情。我做的事情是每一个人都应该做的。”但事实是,每一个人都应该做的事情,还是只有极少数人做到了。在《烟雨任平生》附录中,河南省社会科学院研究员刘倩在文章提到,当时当地知道艾滋病疫情的人不在少数,尤其是地方政府的工作人员,但他们对高耀洁等人揭发疫情却不以为然。有人甚至漠然地说:“(盖子)其实不揭也是这样,底下的情况(上头)早都知道!”

文章中记录,也有村医说道:“1999年就确定很多人得艾滋病了,但上面不让说。现在村里是公开了,也瞒不住了,但对外还是不公开。我是村医,是政府的人,得跟政府保持一致。不然领导知道了会批评,不想干就回家!”

与之相对,在面对大声说出或者保持沉默之时,高耀洁选择了从人本身的角度出发。她在采访中说道:“因为你是人嘛,人就应该维护人的利益。”在人性与强权之间,她选择了人性,也选择了制度的对立面。也正因为对“人”之存在本身的尊重,她不仅做艾滋疫情的“吹哨人”,也与制度长期对抗;不仅调查疫情的真相,也以个人的力量去救济许许多多的患者和孤儿。

高耀洁的努力并未能改变制度。中国官方对非典疫情和新冠疫情在爆发初期的隐瞒,与对艾滋疫情的态度几乎如出一辙,但是高耀洁向我们展现了一个勇敢而真诚的人如何在制度高压之下,依然选择人性的力量,并做出正确的事情。这种力量不只属于高耀洁,也属于其他默默为艾滋患者和艾滋孤儿奔走的人们。他们的持续努力,为艾滋疫情中的死者保留了一点人之为人的尊严——他们不至于在无声无息中死去,没有人知道他们承受的苦难。

书中讲到,2007年,高耀洁获颁美国国际组织“生命之音”颁发的“妇女领导者奖”后,中国政府一度阻止她赴美领奖。最终是希拉里·克林顿亲自出面,中国政府才同意放行。在高耀洁领奖回国后,当地政府更加变本加厉地监控高耀洁,同时还给高耀洁的家人施压,让她无法继续为艾滋疫情的受害者发声。这也是高耀洁为什么在2009年已逾80岁高龄时,毅然出走美国,只为继续发声。

晚年,在病痛和孤独中,高耀洁也依然惦念着那些艾滋孤儿,以及她曾经亲眼见到的垂死的艾滋患者。在与林世钰对谈中,每提及那些受害者,高耀洁都会情不自禁地落泪。

《烟雨任平生》的独到之处,在于口述史中保留了丰富的个人情感和内心独白。这种细腻的情感记录,为理解高耀洁提供了更多层面的信息——高耀洁的正义感,来自于幼时在私塾读到的圣贤书,包括“富贵不能淫,贫贱不能移,威武不能屈”这样的传统中国文化教育。即使到了晚年,高耀洁还能熟背《诗经》、《孟子》等经典。可以看出,她以天下为己任的人生态度,其实早在少年时期就已形成。她坚定的性格,在晚年依然未变,且与她病痛羸弱的身躯形成鲜明对照。

《烟雨任平生》一书记录的,还有高耀洁与家人的感情。高耀洁一直较少谈及家庭,关于她的其它作品中几乎未涉及这一面向。书中写道,早在文革期间,由于她不屈从红卫兵的迫害,其子郭锄非在13岁时被诬陷为“反革命”,入狱三年,成为当时河南省最年轻的政治犯。退休后的她,全身心投入防治艾滋病的工作,政府为迫使她沉默,对其子女施加巨大压力,让孩子们受到很大影响,这也在某种程度上影响了家庭成员之间的感情。林世钰在访谈期间,恰逢高耀洁的女儿前来照料,以及儿子途经纽约探望,由此记录下了她与子女间的情感互动和复杂心理。

书中令人印象深刻的一幕,是高耀洁的90岁生日庆祝。林世钰与友人为她准备了生日蛋糕。虽然长期受病痛困扰,但那一天高耀洁露出难得的笑容。她一生将精力倾注于他人,而这一天的喜悦,似乎才真正属于她自己。这些细节的描写,使高耀洁的晚年生活情境更为立体,令读者仿佛与作者一同坐在她的床边,倾听她的讲述。如她所说,这些故事,包括曾经发生的悲剧,要“留给后人,这是一种贡献”。

本期推荐档案:

相关档案(均为高耀洁的著作):

Gao Yaojie Through Rain and Mist: The Late-Life Monologue of a Noble Soul in Exile

By Bi Shu

In 1996, when 69-year-old retired doctor Gao Yaojie met a rural woman diagnosed with AIDS during a consultation, she had no idea this moment would redefine her life. Starting with this woman, who had been infected through a blood transfusion, Gao began a years-long investigation into the tragedies of impoverished farmers contracting AIDS from blood stations and the government’s culpability. Her persistent efforts exposed the truth of the “Henan blood disaster” to the world, indirectly preventing the catastrophe from spreading further.

The problem had started in the early 1990s. To generate revenue for its healthcare system, the Henan provincial government encouraged rural residents across the province to sell blood to “get rich and escape poverty.” This aggressive development of a “plasma economy” led to the construction of a large number of blood stations. Many of these stations were privately contracted and, to cut costs, failed to screen for Hepatitis B and HIV before blood collection. They also allowed multiple people to share needles and even mixed blood components before reinfusing them back to donors. As a result, HIV spread rampantly through blood sales and transfusions among the rural poor.

Gao was not the first to discover the spread of AIDS through the Henan blood banks. As early as 1993, Henan’s health department discovered that AIDS was spreading among blood donors. In 1995, Wang Shuping, head of a clinic in Zhoukou, Henan Province, had already investigated the scandal and produced a report, but her findings were suppressed by officials. When Gao began her in-depth investigation in 1996 and funded her own AIDS prevention campaigns, she bravely and persistently spoke out amidst official pressure. These efforts were disseminated by China’s media, which were more independent in that era, and was noticed by the international community. The publicity ultimately made the Henan blood scandal known worldwide.

Gao, however, paid a heavy price. In August 2009, at over 80 years old, she left China for the United States, beginning a life in exile. From then until her death in Manhattan in December 2023, she was not able to return to her cherished homeland.

After escaping government surveillance, Gao continued to speak out about China’s AIDS epidemic. In her later years, she authored several memoirs, including The Soul of Gao Yaojie: A Memoir, Gao Yaojie’s Recollections and Reflections, and Gao Yaojie Remembering the Past, all of which are a testament to her life. She spent most of her time in the turbulent 20th-century China, enduring a life of hardship. Born in 1927, she had her feet bound as a child, attended a traditional private school, and fled during wartime. She worked as a gynecologist for decades and suffered greatly during the Cultural Revolution.

In China, she was named a “Person of the Year” by China Central Television in 2003 and nominated for the same award by Southern Weekend. In 2004, Southern People Weekly listed her as one of “Fifty Public Intellectuals Influencing China.” Internationally, she received the Jonathan Mann Award for Global Health and Human Rights in 2001, was named an “Asian Hero” by Time magazine in 2002, and had asteroid 38980 named “Gaoyaojie” in 2007.

However, Gao’s heroic stature often overshadowed her humanity as an ordinary person. Her biography, Through Rain and Mist: The Oral History of Gao Yaojie, offers a uniquely intimate perspective and precious material for understanding Gao, covering not only her stories as a doctor and advocate for AIDS patients but also her rarely discussed yet complicated relationship with her family, her lesser known experiences in exile in New York City, and her emotions and inner thoughts as she battled illnesses toward the end of her life.

The book’s author, Lin Shiyu, was a journalist in China for many years before moving to the U.S., where she has documented the lives of Chinese people living abroad. To write Through Rain and Mist, she visited Gao’s apartment near Columbia University dozens of times for in-depth interviews. In her later years, Gao was often bedridden and hospitalized with serious illnesses, and many conversations had to be conducted through written notes. The author organized Gao’s oral accounts and notes to present her life in the U.S. and thoughts.

After embarking on her journey to help AIDS patients, Gao witnessed their despair and the countless families destroyed by the disease, leaving many children orphaned. This experience made her empathize with the pain of the victims and fueled her determination to speak the truth.

Through Rain and Mist provides a detailed account of Gao’s visits and her care for AIDS orphans. Still, after the book was published, Gao stated, “I didn’t do anything great. What I did is what everyone should do.” Yet, the reality is that only a very small number of people actually did what everyone should have done. In the book’s appendix, Liu Qian, a researcher at the Henan Academy of Social Sciences, mentioned in an article that many people knew about the AIDS epidemic at the time, especially local government employees, but they were indifferent.

Liu’s article records a village doctor saying, “It was confirmed in 1999 that many people had AIDS, but we weren’t allowed to talk about it. Now it’s public in the village because it can’t be hidden, but it’s still not public to the outside world. I’m a village doctor, a government employee, so I have to be consistent with the government. Otherwise, the cadres will criticize me and say that if I don’t want to do it, I can just go home!”

In contrast, when faced with the choice between speaking out and remaining silent, Gao always chose the humane way. She said in an interview, “Because you are human, a human being should protect human interests.” Between humanity and an authoritarian system, she chose humanity, thereby placing herself in opposition to the system. It was this respect for human existence that made her not only a whistleblower but also a long-term adversary of the system, using her own resources to help countless patients and orphans.

While Gao’s efforts couldn’t change the system—the Chinese government’s concealment of the initial SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks was nearly identical to the official attitude toward the AIDS epidemic—she showed us how a brave and sincere person, under immense systemic pressure, can still choose the power of humanity and do the right thing. This power belonged not only to Gao but also to others who quietly worked for AIDS patients and orphans. Their continuous efforts salvaged some dignity for the dead, ensuring they didn’t perish silently without anyone knowing about their suffering.

The book recounts that in 2007, when Gao was awarded the Global Women’s Leadership Award by the U.S. organization Vital Voices, the Chinese government initially tried to prevent her from traveling to the U.S. to accept it. It was only after Hillary Clinton personally intervened that the Chinese government relented. After Gao returned, local authorities intensified their surveillance and even pressured her family to silence her, which is why she left for the U.S. in 2009.

In her later years, amidst illness and loneliness, Gao still thought of the AIDS orphans and the dying patients she had seen. In conversations with Lin, she would get emotional and cry every time she mentioned the victims.

Through Rain and Mist is unique because its oral history format preserves a wealth of personal emotions and inner monologues. This detailed emotional record provides readers with a deeper understanding of Gao—her sense of justice stemmed from the classical texts she read as a child, including teachings like “to be unmoved by riches and honors, to be unswayed by poverty and meanness, and to be unbent by force and power.” Even in her later years, she could still recite classics like the Book of Songs and the Mencius. This shows that her life philosophy of “taking the world as one’s own responsibility” was formed early on. Her unyielding character remained unchanged in her old age, a striking contrast to her frail body.

The book also documents Gao’s relationship with her family, a topic rarely discussed in her other works. According to Gao’s oral accounts, reveals that during the Cultural Revolution, because she would not submit to the persecution of the Red Guards due to her family background as landowners, her 13-year-old son, Guo Chufei, was falsely accused of being a “counter-revolutionary” and imprisoned for three years, becoming the youngest political prisoner in Henan Province. After her retirement, when she dedicated herself to AIDS prevention, the government placed immense pressure on her children to silence her, which significantly affected their lives and strained their familial bond. During her interviews, the author was able to document the emotional interactions between Gao and her children when her daughter came to care for her and her son visited.

One particularly memorable scene in the book is Gao’s 90th birthday celebration. Lin and a friend prepared a birthday cake for her. Although she had long been afflicted with illness, Gao showed good spirits on that day. She had dedicated her life to others, and the joy of that day seemed to truly belong to her. These details make Gao’s later life more vivid, making readers feel as if they are sitting by her bedside, listening to her tell her stories. As she said, these stories, including the tragedies, needed to be told as her contribution to later generations.

Recommended archive:

Lin Shiyu: Through Rain and Mist: The Oral History of Gao Yaojie

Related archives (all by Gao Yaojie):

The Soul of Gao Yaojie: A Memoir (English version available for purchase online)

Gao Yaojie’s Recollections and Reflections

Gao Yaojie Remembering the Past

Ten Thousand Letters: Gao Yaojie's Observations on the Living Conditions of AIDS and STD Patients