纪录片《上访》:信访悖论之下,卑微的个体如何与国家相处

Documenting the Life of Petitioners: How Individuals Navigate State Bureaucracy Amidst the Paradox of China’s Petitioning System

作者:荒原

By Huang Yuan

The English translation follows below.

上访一度是中国特殊而引人注目的社会现象。了解上访制度和上访者经历的最佳影像资料,要属纪录片《上访》。

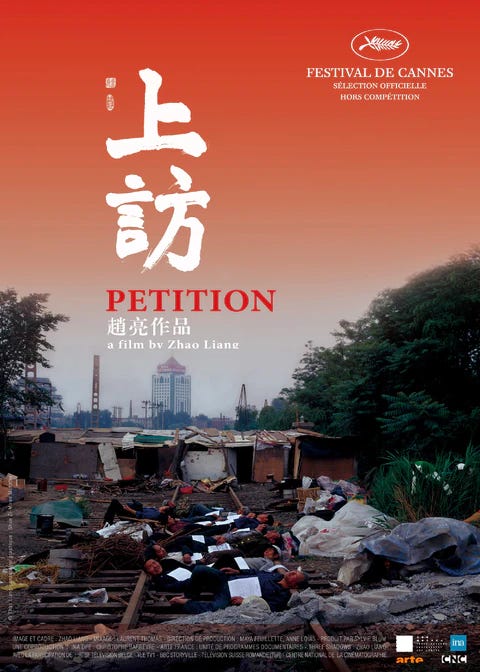

《上访》是独立导演赵亮的作品。该片有两个版本,国际版长约两个小时,曾入选海外的多个电影节。另一个国内版长达五个多小时。国内版由《众生》、《母女》、《北京南站》三部分组成。2009年,在宋庄举行的第六届中国纪录片交流周中,两个版本各放映了一次。赵亮也获得了中国独立纪录片电影节的“独立精神奖”。

《众生》串联起上访者的不同故事,他们因不同的原因聚集在北京南站幸福路周围的“上访村”。导演赵亮在片中力图全景式地展现上访人群的经历,解释什么是上访,人们为何要上访,以及如何上访。

《北京南站》将镜头对准奥运会之前面临被改造的上访村。在这里,访民们基本是十几、二十个人同处狭窄一室,上下铺相连。有些人则在窝棚里、桥洞下居住,天热时还会睡马路边或广场上。他们到菜市场捡菜叶,就馒头吃。有的人靠捡垃圾、卖地图或乞讨为生,以最低消费解决衣食住行。另外,面对时不时就可能出现的截访人员,他们保持着高度警惕,行李常是半打包状态,以防当局突然驱逐,抓人或强拆掉他们的“住所”。

上访者之所以聚集在这里,主要是由于中共中央办公厅和国务院办公厅、全国人大常委会办公厅、及最高人民法院的接待室都在附近。上访村有不少是长达十年甚至数十年的上访老户,有的人几乎把一生的时间都消耗在了这里。

按照中国官方的说法,上访是有中国特色社会主义的一项制度。1951年,中共颁布《关于处理人民来信和接见人民工作的决定》,这算是信访制度的开始。也就是对那些正常的司法渠道解决不了的问题,留下一个所谓民意上达的口子。但后来中国政治运动不断,实际上法律制度处于废弃状态。一直到1978年,文革结束,“改革开放”启动,那些曾经在文革中被打倒而饱受痛苦的中共高层当权者,也认为国家不能没有法律制度,所以着手恢复检察院、司法部,以及律师行业。1982年,国家通过《党政机关信访工作条例(草案)》,以突击性解决文革的遗留问题,就如官媒报道,“信访工作迎来了新时期”。而在那个时期,由于当时中共领导人胡耀邦的推动,从“反右”到“文革”等政治运动中的很多冤假错案,也确实通过信访得到了解决。

但在那之后,信访并没有成为一个社会瞩目的焦点。

1990年代之后,尤其是新世纪的前十年,中国经济高速发展,各种社会矛盾层出不穷,群体性事件时有爆发。尤其是城市化进程中,各省普遍的“强拆”行为,以及食品安全、环境污染等问题,在地方上都难以得到解决,一个重要的原因是中国没有独立的司法。原本应通过法律来处理的问题,由于司法腐败,以及人们对法律的不信任,最终还是要回到“信访”这个由政府官员主导的路径上来。

对访民来说,绕开地方政府,直接到北京,要求中央解决问题,或许有一种深层的社会心理:传统上,人们倾向认为,皇帝是好的,他只是被贪官蒙蔽,而皇帝派来的“钦差大臣”,有可能就是一个清正廉洁的官员,而他能帮助人民讨回公平和正义。“越级上访”,也就是到北京去找最高一级的政府,有时就成了访民的一种执念。

另外一个背景是,2000年以后,互联网在中国迅猛发展,媒体、知识分子对公共事件积极发声,维权运动方兴未艾,整个社会的言论环境相对宽松。访跨省进京的访民,是一个重要的维权力量,也暂时还没有被纳入官方的打击对象。

上述这些,都是纪录片《上访》拍摄的背景。据赵亮导演在媒体访谈中介绍,1996年,他结束了在北京电影学院的进修课程,在北京停留的那段时间,无意中发现了上访村的存在,从那以后,他就把镜头对准了北京南站这片访民聚集的区域。而且,这一拍就是10多年,一直到2006年上访村因为北京奥运场馆建设的原因而被彻底拆除。

《上访》的拍摄跨度,注定它恰好记录了中国经济高速发展、各种社会问题大爆发的时期,各地上访民众的众生相。也间接反映出,信访这个所谓“表达民意”的制度设计,在中国的现实中已经破产,而成为一个荒谬的存在。

在赵亮的镜头里,每天,访民早早怀着希望出门,晚上总是失望而回。就像一名上访者所说,“你还没领着表,排到你那儿已下班了,(只得明天再来),好不容易领到,就像圣旨似的……交上去心里嘴上都祈祷啊,领导啊,你可给我好好开封信,能叫下边给我解决,辛辛苦苦,等开了信,拿回(地方)去,又成废纸了。”

在中国,信访问题常涉及多个部门,导致复杂的“信访综合症”,由于信访部门并不具有解决问题的实际权力,加上信访机构庞杂,统领,各机构推来推去,上访者如同无头苍蝇,来回跑动,问题却始终解决。

2005年开始,信访量成为考核地方政府的核心指标。换言之,一个地方如果有人到本地或北京上访,就关系到当地政府的工作成绩,说明他们的无能,是要受到上级批评甚至惩处的。然而,各地政府并不能解决因司法腐败、征地拆迁、医疗事故或交通事故处理不公,甚至只是邻里矛盾带来的大量上访问题。所谓越级上访一直在频繁发生。虽然通过信访被解决的问题,少之又少,但没有其它维权路径的民众,依然把上访当作最后一根救命稻草。

《众生》中,经营煤矿的河南私营老板罗宏全,在当地受到不公待遇后,到北京上访,随后被当地警方以莫须有的罪名全国通缉。在他常年上访之下,地方政府也承认他有理,但却拒绝承担法律责任和给他恢复名誉。

中央希望众多问题解决在基层,地方却无力解决,在一个压力型体制下,为维稳和规避问责,地方政府则常采取所谓“劫访”(使用暴力拦截上访人,包括指使黑社会打击报复,甚至跟当地或上级信访部门勾结,通风报信,半路截走)手段,从北京劫持上访者回到地方。有时甚至用诬陷、罚款、拘留、劳教、判刑、连坐等手段压制上访者,致使矛盾不断激发,问题积累发酵,对上访者造成持续伤害,形成恶性循环。

群众知道地方政府怕上访,所以遇到问题,就优先考虑上访。民众越是激烈上访,地方政府越是采取更为严厉的办法来对付。上访过程中遭受的不公或打击,甚至超越最初上访的初衷,成为访民继续和持续上访的催化剂。罗宏全就是这样。如同《上访愁》所唱,“自从我走上了上访路,从此我就没有回头。”

这在《母女》中也有呈现,母亲看到官媒上报道了自己痛恨的当地官员,更坚定了其继续上访的决心。“哪怕剩一口气,我都告。”她说,“反正这一生已经完了。”

影片中还反映了一种“销号”行为。一些地方官员试图用公款贿赂上级(中央)的信访部门销号,也就是注销已登记的群众来访,或拒绝登记来访,这样就不会影响到自己的政绩。这也导致上访者把地方和中央的信访部门视为共谋,反而激发他们更坚决地告下去。

信访带来的绝望情绪,让一些访民的行为更加激烈,包括到天安门、驻华领馆等政治敏感地区“非正常上访”,甚至采取跳河、自焚等激烈手段。《众生》中的一幕让人印象深刻:一个上访者在天安门广场发传单,很快就遭到抓捕。

一些研究表明,在中国的社会背景下,信访制度被赋予了双重冲突的使命,既要充当“减压阀”(化解矛盾),又要担任“压力表”(监控基层)。但因为权力来源于上级,地方官员首先要对上负责,以求自保——这就必然凌驾于“减压阀”的功能,不能“让人民群众满意”。也正因此,基层政府的行为必然是扭曲的,陷入“越维稳越不稳”的循环。正如《上访》中,维权律师任华所说的,“信访口实际上不但不能解决问题,还像一堵墙一样把这个问题给堵住了,没有解决,拖延着,让问题更复杂。”

中国社会科学院学者于建嵘为了做信访制度调查,曾住进上访村一个多月,他的调查结果显示,通过信访解决问题的比例只有千分之二,也就是1000个访民中仅有两人解决了问题。因为先天不足,信访制度只能成为显示政府“重视民意”的装饰品和门面。

上访村核心地带名为“幸福路”。但事实上,这里是一个苦难的集中展示地。当民众一旦开始上访,基本都会丢掉工作,甚至不断失去自由,被监视,影响家人子女。上访者的故事,往往从一个人的苦难,变成了一个家庭的悲剧。

影片结尾,北京即将迎来举世瞩目的奥运会,国家看上去喜庆洋溢,被遮蔽的卑微哀伤的上访者,则无人知晓。上访村被彻底拆除,访民们连仅有的生活用品没抢出就被驱散。上访村没有了,但上访者的故事并没结束,他们被迫搬至更远的地方,慢慢再聚集成新的上访村。但可以确定的是,近年来随着中国社会的管控越加严酷,严防民众的聚集与抗议,《上访》中的那些场景已经很难在中国再现。从这个意义上,赵亮导演的作品,留下了一段难以复刻的样本——记录下卑微的上访者,如何面对强大的国家,不轻言放弃,但却搭上了自己的正常人生。

除了《上访》,导演赵亮还曾拍摄过记录圆明园强拆艺术村的《告别圆明园》、《罪与罚》、《在江边》等纪录片。他说过,自己的作品大都关注的是个体与国家机器之间的关系。对时时弥漫在片中的荒诞感,他曾在访谈中说过,并不是他主动去捕捉这种荒诞性,“而是整个社会都充斥着各种各样的矛盾、荒诞,不需要我去刻意寻找。”他也说过,拍《上访》,是出于一种使命感,觉得自己应该在这样的一个时代里,记录下个人和社会现实的交锋。

如今中国官方宣称已建成网上信访信息系统,“网上受理,网下办理”。而且因为严格的规定,上访可能被以扰乱治安秩序而治罪,甚至可能影响到子女上学、就业等,至少到北京上访的人已相应减少。但上访的本质并没有改变。信访悖论的根源其实还在于中国依然缺乏宪政、民主,以及真正的法治。纪录片《上访》,就呈现了在这样一个结构性困境里,个体与国家机器的关系,以及人们卑微而倔强的反抗。

本期推荐档案:

Documenting the Life of Petitioners: How Individuals Navigate the State Bureaucracy Amidst the Paradox of China’s Petitioning System

By Huang Yuan

Petitioning was once a unique and notable social phenomenon in China. One of the best sources for understanding China’s petitioning system and the experiences of petitioners is the documentary Petition.

Petition, a film by independent director Zhao Liang, has two versions: the international version is about two hours long and has been selected for several film festivals, while the domestic version is over five hours. The domestic version is composed of three parts: The Masses, Mother and Daughter, and Beijing South Railway Station. In 2009, at the 6th China Documentary Film Week in Songzhuang, both versions were screened. Zhao Liang also received the “Independent Spirit Award” at the China Independent Documentary Film Festival.

The Masses connects the different stories of petitioners who, for various reasons, gather in the “petition village” around Beijing’s South Station and Xingfu (Happiness) Road. In the film, Zhao attempts to present a panoramic view of the petitioners’ experiences, explaining what petitioning was, why people did it, and how they went about it.

Beijing South Railway Station focuses on the petition village facing redevelopment before the Olympic Games. Here, petitioners typically lived in cramped rooms with 10 to 20 people, sleeping on connected bunk beds. Some lived in shacks or under bridges, even sleeping on the streets or in squares during the summer. They scavenged for discarded vegetables at markets to eat with steamed buns. Others survived by collecting trash, selling maps, or begging, getting by with the lowest possible expenses for food, clothing, and shelter. Furthermore, they remained highly vigilant against the ever-present petition interceptors, keeping their belongings half-packed in case of a sudden government eviction, arrest, or demolition of their temporary homes.

Petitioners gathered primarily because the reception offices for the General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, the General Office of the State Council, the General Office of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, and the Supreme People’s Court were all nearby. Many of the villagers were veteran petitioners who had been petitioning for over a decade, with some spending almost their entire lives there.

According to the Chinese government, the petitioning system is a socialist institution with Chinese characteristics. In 1951, the Communist Party issued the “Decision on Handling People’s Letters and Receiving People’s Work,” which is considered the origin of the petitioning system. It was meant to be an outlet for public opinion for issues that could not be resolved through regular judicial channels. However, a series of political campaigns followed, and the legal system was effectively abandoned. It was not until 1978, after the Cultural Revolution ended and Reform and Opening Up began, that some high-level Communist Party officials who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution also believed that the country could not function without a legal system. They began to restore the procuratorates, the Ministry of Justice, and the legal profession. In 1982, the state passed the “Regulations on Petitioning Work for Party and Government Organs (Draft)” to address the lingering issues from the Cultural Revolution. As state media put it, “petitioning ushered in a new era.” During that period, driven by then-leader Hu Yaobang, many miscarriages of justice from political campaigns like the Anti-Rightist Campaign and the Cultural Revolution were resolved through the petitioning system.

But immediately after that, petitioning did not become a major focus of public attention.

After the 1990s, especially in the first decade of the new century, China’s economy developed rapidly, leading to a surge in social conflicts and frequent outbreaks of mass incidents. Issues like widespread forced demolitions during urbanization, food safety, and environmental pollution were difficult to resolve locally. A key reason for these lasting conflicts was the lack of an independent judiciary. Problems that should have been handled through the legal system were instead funneled back into the petitioning system, which is led by government officials, due to judicial corruption and public mistrust of the law.

For petitioners, bypassing local governments and going directly to Beijing to seek a resolution from the central government may be rooted in a deep-seated social psychology: traditionally, people tend to believe the emperor is good but is misled by corrupt officials, and an imperial envoy sent by the emperor could be an honest official who can help people achieve fairness and justice. “Skip-level petitioning”—going to Beijing to petition the highest level of government—sometimes becomes an obsession for petitioners.

Another contributing factor was the rapid development of the Internet in China in the early 2000s. The Chinese media and intellectuals were actively speaking out on public issues, and the movement to defend rights was on the rise, creating a relatively open environment for speech. Petitioners traveling across provinces to Beijing were a significant force for rights protection and had not yet become a target for official crackdown.

These factors form the backdrop for the documentary Petition. According to director Zhao Liang in media interviews, in 1996, after finishing his studies at the Beijing Film Academy, he happened upon the existence of the petition village during his time in Beijing. From then on, he focused on the area where petitioners gathered near Beijing South Railway Station. He continued to film for more than 10 years, until the petition village was completely demolished in 2006 to make way for Beijing’s Olympic venues.

The filming span of Petition means it captured a period of rapid economic growth and a massive explosion of social problems in China, showing a cross-section of petitioners from all over the country. It also indirectly reflects how the petitioning system, supposedly designed to express public opinion, has failed and become an absurd institution.

In Zhao Liang’s lens, every day, petitioners leave with hope in the morning and return disappointed in the evening. As one petitioner says, “You have not even gotten a form yet, and by the time your turn comes, they are already off work, so you have to come back tomorrow. When you finally get one, it is like an imperial edict. You pray silently and out loud when you hand it in, ‘Please, cadre, give me a good letter so the local government will solve my problem.’ After all that hard work, you take the letter back [to your locality], and it becomes a useless piece of paper again.”

In China, petitioning issues often involve multiple departments, leading to a complex “petitioning syndrome.” Since petitioning departments lack the actual power to resolve problems, and the system is vast and disorganized, petitioners are often pushed from one agency to another, running around while their issues remain unresolved.

Starting in 2005, the number of petitions became a core metric for evaluating local governments. In other words, if someone petitioned locally or in Beijing, it would reflect negatively on the local government’s performance, signaling their incompetence and leading to criticism or even punishment from superiors. However, local governments were unable to resolve the large number of issues stemming from judicial corruption, land expropriation, forced demolition, unfair handling of medical or traffic accidents, or even simple disputes between neighbors. The so-called skip-level petitioning continued to occur frequently. Even though very few problems were resolved through the system, people with no other way to defend their rights still saw petitioning as a last resort.

In The Masses, Luo Hongquan, a private coal mine owner from Henan Province who suffered injustice locally, goes to Beijing to petition, only to be placed on a nationwide wanted list by his hometown’s local police under fabricated charges. After years of petitioning, the local government eventually admitted he was in the right but refused to take legal responsibility or restore his reputation.

While the central government wanted problems solved at the local level, local governments were often powerless to do so. Under a pressure-driven system, to maintain stability and avoid accountability, local governments often resorted to tactics of interception—using violence to stop petitioners, including hiring gangsters, or even colluding with local or higher-level petitioning departments to get tips and intercept petitioners on their way back from Beijing. Sometimes they used false accusations, fines, detention, re-education through labor, sentencing, and collective punishment to suppress petitioners, which only exacerbated conflicts and intensified problems. This created a vicious cycle and caused unending harm to petitioners.

The public knows local governments fear petitions, so when they encounter a problem, they prioritize petitioning. The more intense the petitions, the more severe the methods local governments use to deal with them. The injustices or crackdowns suffered during the petitioning process often become a catalyst for petitioners to continue their fight, even surpassing the original reason for their petition. Luo Hongquan’s story is a prime example. As the song “Petitioner’s Sorrow” from the film says, “Since I embarked on the petitioning path, I have never looked back.”

This is also shown in Mother and Daughter, where the mother sees a local official she despises being reported on by state media, which strengthens her resolve to continue petitioning. “Even if I am on my last breath, I’ll still sue,” she says. “My life is already over anyway."

The film also shows a practice of writing off cases. Some local officials try to bribe higher-level (usually central) petitioning departments with public funds to write off petitions—canceling registered visits or refusing to register them at all—so their performance is not affected. This leads petitioners to see local and central petitioning departments as co-conspirators, which only strengthens their determination to continue their fight.

The despair caused by the petitioning system drives some petitioners to more extreme actions, including “abnormal petitioning” in politically sensitive areas like Tiananmen Square or foreign embassies, and even resorting to drastic measures like jumping into rivers or self-immolation. One scene in The Masses is particularly memorable: a petitioner distributes leaflets in Tiananmen Square and is quickly arrested.

Studies have shown that within China’s social context, the petitioning system is given a dual, conflicting mission: to act as a “pressure-release valve” (diffusing conflicts) and a “pressure gauge” (monitoring the grassroots). But because power flows from the top down, local officials must first be accountable to their superiors to protect themselves—which inevitably takes precedence over the “pressure-release valve” function and fails to “satisfy the people.” Consequently, the behavior of grassroots governments is inherently distorted, caught in a cycle of “the more they try to maintain stability, the more unstable things become.” As the rights lawyer Ren Hua says in Petition, “The petitioning channel actually not only fails to solve problems but also acts like a wall, blocking them off, delaying them, and making them more complicated.”

Yu Jianrong, a scholar at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, once lived in a petition village for over a month to research the petitioning system. His findings showed that the proportion of problems resolved through the system was only 0.2%, meaning only two out of every 1,000 petitioners had their issues resolved. Because of its inherent flaws, the petitioning system can only serve as a decorative facade to show that the government values public opinion.

The core area of the petition village is called “Xingfu Road,” or “Happiness Road.” In reality, it is a hub of concentrated suffering. Once people start petitioning, they usually lose their jobs and may even lose their freedom, be monitored, and have their families and children affected. A petitioner’s story often turns from an individual’s tragedy into a family’s tragedy.

At the end of the film, Beijing is about to host the highly anticipated Olympic Games, and the country appears full of celebration. The humble, grieving petitioners, however, are hidden from view and unknown to the world. The petition village is completely demolished, and petitioners are driven away before they can even grab their meager belongings. The petition village is gone, but the petitioners’ stories are not over. They are forced to move to more distant places, slowly forming new petition villages. However, with the increasingly severe social control in China in recent years, which strictly prevents public gatherings and protests, the scenes in Petition are now difficult to replicate. In this sense, director Zhao Liang’s work leaves behind a record that is difficult to recreate—documenting how humble petitioners, facing a powerful state, refuse to give up but ultimately sacrifice their normal lives.

In addition to Petition, Zhao has also made documentaries such as Farewell to Yuanmingyuan (which documents the forced demolition of an art village), Crime and Punishment, and On the River. Zhao said that most of his works focus on the relationship between individuals and the state machine. Regarding the sense of absurdity that permeates his films, he said in an interview that he does not actively seek it out: “The entire society is filled with all kinds of contradictions and absurdity, so I do not need to deliberately look for it.” He also said that he filmed Petition out of a sense of mission, feeling that he should, in such an era, document the clash between individuals and social reality.

Today, the Chinese government claims it has built an online petitioning information system with “online submission and offline handling.” Moreover, due to strict regulations, petitioning can be criminalized as disturbing public order, and it can even affect the petitioners’ children’s education and employment. Consequently, the number of people petitioning in Beijing has decreased. However, the essence of the petitioning system has not changed. The root of the petitioning paradox lies in China’s continued lack of constitutionalism, democracy, and genuine rule of law. Petition presents the relationship between individuals and the state machine within this structural dilemma, as well as their humble yet stubborn resistance.

Recommended archive:

Thank you, a new film for me. I wish I would have known it to include in my Substack post, see below. Here is quote that floated out:

“Throughout the country’s [China] long history countless emperors have tried to keep the Mandate of Heaven by annihilating those who threatened their rule.” Ezra Vogel

I found this for our viewers as your links are to Chinese only versions:

Petition (2009) Liang Zhao Documentary. Imperfect Plan, May 31, 2024. 2:03:53

Over the course of 12 years (1996-2008), director Zhao Liang follows the "petitioners", who travel from all over China to the nation's capital, Beijing, to make complaints about injustices committed by authorities in their home towns and villages. Most petitioners wait for months or years for their grievances to be heard, while they live in makeshift shelters around the southern railway station of Beijing. All types of cases are represented: mothers of abused young soldiers, farmers thrown off their land, workers from demolished factories, and more. The documentary explores the Sisyphean lives of the petitioners as they contend with the authorities and their own families in their struggle for restitution and survival. At times it was filmed with hidden cameras smuggled into government offices.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTe09EGk6Rs

Here is from my Substack

MUSEUM OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY BY THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY (CCP) MAO TO XI

Holding Ideologues Aiding and Abetting the CCP Morally Accountable

https://responsiblyfree.substack.com/p/museum-of-crimes-against-humanity

which includes a video by three Chinese Communist Party worshippers, Matthew Ehret, Cynthia Chung and Jeff Brown, which is on my Substack and here is the Youtube

RTF Dialogues: A Journey with Jeff J. Brown Through China's History, Political-economy and Culture

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95f62yJt9O4

And here is the transcript I pulled out which is on this “Petition” theme. At the time I published this Nov 16, 2024 I did not know about Liang Zhao’s documentary.

Here are Brown’s unbelievably sycophantic words:

BROWN 1:13:10 “YEAH YOU KNOW DEMOCRATIC DICTATORSHIP OF THE PEOPLE UH IT'S IT'S JUST AN IT'S AN UNFORTUNATE CHOICE OF WORDS for westerners because it contains this upsetting cognitive dissonance and and and it really bothers really bothers people IT'S ACTUALLY A FROM KARL MARX BUT IN A NUTSHELL IT'S MAO'S BOTTOM UP MASS LINE POLICY MAKING WHERE THEY LISTEN TO THE PEOPLE AND THEN THE MAJORITY RULES ONCE THE MAJORITY DECIDES IT'S LENIN'S DEMOCRATIC CENTRALISM AND LENIN'S DEMOCRATIC CENTRALISM is everybody top to bottom including the minority who didn't get their wish this time NEEDS TO BACK THE PLAN FOR THE GOOD SO YOU JUST FIT IN AND AND AND AND AND SUPPORT UH THE THE DECISION OF THE MAJORITY in the meantime the decision is constantly assessed and reassessed and adjusted for maximum benefit with Mao's you know mass line these poles and surveys to check the zeitgeist (1:14:17) and and again this has ANCIENT ROOTS WHICH I'VE ALREADY EXPLAINED NOW THAT'S THAT'S AT THE AT THE GENERAL LEVEL UH IF SOMEONE HAS A GRIEVANCE THAT HAS NOT BEEN FOR THEM SATISFACTORILY DECIDED THEY SHOULD FIRST GO TO THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND MAKE A WRITTEN CLAIM MAKE A WRITTEN REPORT of what's going on you know there's there's you know sewage you know whatever coming out in our garden or whatever it could be anything you know someone who was illegally who was who they thought was unjustly arrested or it (1:14:58) could be just one of a thousand different things and IF THEY'RE STILL UNHAPPY THEY CAN KEEP TAKING IT UP TO THE COUNTY AND THEN IF THE COUNTY DOES NOT OFFER A SATISFACTORY ADVICE UM UH COUNCIL THEY CAN GO TO THE PROVINCIAL THE PROVINCE THE PROVINCIAL CAPITAL AND EVEN THE NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE LEVELS WITH THE UH WITH THE UH CPP UM UM CC THE EXECUTIVE and then also the national people's going every every time the the um the NPC meets and every time the cppcc meets in beijing there's always a bunch of people who (1:15:45) feel who feel like they have really been badly treated and are looking for relief um but and then for groups who feel wrong this is something that just blows westerners away CHINA HAS THREE TO 500 PUBLIC PROTESTS A DAY ALL OVER THE COUNTRY…BABA BEIJING ACTUALLY LIKES THESE PROTESTS because it exposes bad governance malfeasance corruption and i've seen protests on a number of occasions of myself i mean i've seen them hi you know they're out there they they protest you know and THEY DON'T GET MACED AND GET YOU KNOW PUT IN CYCLONE FENCE CAGES LIKE IN THE UNITED STATES AND ALL AROUND THE WEST THEY DON'T GET WATER CANNONED AND BEATEN UP AND IT'S ALL VERY VERY RESPECTFUL (1:17:19) and that that's why I THINK CHINA'S IS THE MOST PEOPLE DRIVEN DEMOCRACY IN THE WORLD I THINK IT'S THE MOST CONSENSUAL”.