八十年代的一束思想之光:《青年论坛》与胡耀邦的交错命运

An Intellectual Beacon of the 1980s: The Intertwined Fates of Youth Forum and Hu Yaobang

作者:笑蜀

By Xiao Shu

The English translation follows below.

1980年代的中国,武汉的《青年论坛》是一份与上海《世界经济导报》齐名的思想杂志,二者被并称为“一报一刊”。它们都积极探讨自由、民主议题,触及当时敏感的政治神经,为中国人的自由思想启蒙起到了不可估量的巨大作用。但二者都命途多舛——《世界经济导报》在1989年“六四”事件后被全面停刊;《青年论坛》则在仅仅创办四年之后,就在1987年的“反自由化运动”中被迫停刊。八十年代的一道思想之光,就此熄灭。

时隔30余年后,当年《青年论坛》的主编李明华出版了《八十年代的一束思想之光——〈青年论坛〉纪事》一书,以亲历者之眼,见证、记录了这束制度裂缝中的思想之光如何被点燃,以及这场体制内外“共谋”的思想实验如何被迫停摆。与此同时,原中共中央总书记胡耀邦之子胡德平与《青年论坛》的密切关联,也开始被更多人知晓。

夹缝中的呼吸:“真理标准”大讨论带来的思想地震

1976年毛泽东去世,文化大革命旋即结束,但紧接着的1977年2月,“两个凡是”(指“凡是毛主席作出的决策,我们都坚决维护;凡是毛主席的指示,我们都始终不渝地遵循”)的发布,又一度让中国社会陷入迷惘与恐惧,对毛的历史评价成了当时中国政治禁忌的最后一道堤坝。但正是在这道堤坝的震颤中,思想解放的暗潮开始涌动。

《〈青年论坛〉纪事》一书的作者李明华,回忆了当时中国社会的思想背景。他认为,真正的思想解放并非凭空迸发,而源于制度结构的自我松动。1978年的十一届三中全会、“真理标准大讨论”,以及1981年《关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议》,犹如一场场地震,在中国的政治中心撕开一道道裂缝,那些自由思想的火焰,才得以从裂缝中喷薄而出。

在这一场场思想地震中,“真理标准”的大讨论,最具象征性与冲击力。这场邓小平支持下的大讨论,既是学理辩论,也是制度博弈,突破了“两个凡是”的话语禁锢,给出答案——“实践是检验真理的唯一标准”。

但与此同时,这场讨论注定并不会真正触动权力结构本身——思想的开放因此呈现出双重性:一方面,它为知识分子提供了重新发现“人”的合法性窗口;另一方面,它依旧依赖最高权力的庇护,而缺乏制度性保障。于是,思想解放的空间带有了一种“权力赐予”的性质——它不是公共政治的自然生成,而是危机治理中的副产品。

这种微妙局面直接塑造了八十年代思想生态的独特节奏:自由的空气弥漫,但随时可能消散;思想的边界扩张,但始终处于试探之中。就如李明华回忆中所说,这是一种“节拍政治”——开放与收紧交替出现,形成一种非线性的制度律动。事实上,在1980年代初到中期,思想界与社会文化领域得以呈现短暂的繁荣,从“文学热”到“文化热”,再到各类青年刊物的兴起,都与这种结构性裂缝密切相关。

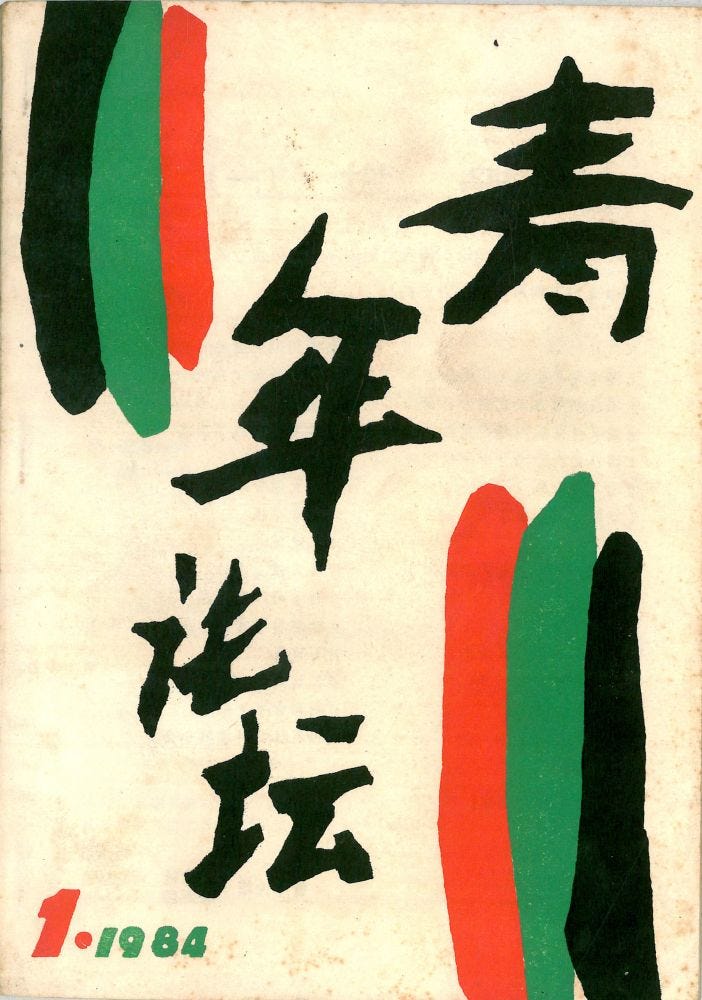

正是在这一背景下,《青年论坛》以“夹缝的产物”姿态登场。1984年8月,《青年论坛》在武汉创刊,由湖北省社会科学院领导,为双月刊,同年11月发布了创刊号。从彼时起,到1987年被迫关闭,《青年论坛》共出版14期,其中有8期的主题都是“自由”。第一期的重磅文章之一就是胡德平的《为自由鸣炮》。文章发表后,被官方媒体集体转载,轰动一时。1986年的7月号、9月号,则连续发表胡平的《论言论自由》,后又发表闵琦的《出版自由与马克思》,以及召开“首都各界人士座谈《论言论自由》”的讨论会。

虽然自创刊以来就倡导自由,但《青年论坛》毕竟是在夹缝中生存,在杂志选题上往往要在政治禁忌的边缘上“走钢丝”。例如1983年中共发起“清除精神污染运动”后,武汉学界已感受到高压气氛,刚刚创刊的《青年论坛》也难以避免地受到影响。为此,李明华与几位同仁选择了“曲线保全”的策略:并不正面反击“清污运动”,而是通过发表“青年成长”、“大学生思考”等中性议题,为青年人的思想保留一丝呼吸空间。

1986年底,当“反自由化”的政治风潮骤然袭来,《青年论坛》再一次陷入存亡困境。刊物原计划推出一个专题,讨论“青年与未来的责任”,部分作者试图在其中嵌入对“政治体制改革”的呼吁。但在风云突变的背景下,这期被迫撤换为相对安全的“青年文学与审美”主题,刊头也增加了“与党的整党精神保持一致”的字样。这种自我审查与策略性妥协,揭示出思想解放如何被迫依附于时局节奏:一旦裂缝关闭,空间立即塌陷。

正是这些个案,让我们得以窥见1980年代思想解放的真实样貌:它既非浪漫化的自由冲动,也非彻底体制外的异议实践,而是一种在权力夹缝中不断调适的制度实验。青年论坛的编辑们并不天真,他们深知“自由的气候”随时可能中止,因此不断在文字、版面与话语之间寻找弹性余地。这种“有限自由”与“被动妥协”的叠加,恰恰构成了八十年代思想解放的核心张力。

这种“夹缝中的呼吸”之所以可能,还与胡耀邦密切相关。1983年“清污”期间,胡耀邦在上海讲话中直言“不要随便给青年扣帽子”,为文化界与青年刊物撑起了一把防护伞;1985年,他在中央会议上批评中宣部的思想钳制,要求“对青年多一点宽厚宽松”,直接影响了新的中宣部部长朱厚泽上任后的一系列松绑政策。李明华回忆,当时《青年论坛》编辑部流传一句话:“只要胡书记在,北京的风不会全部吹到武汉来。”这种庇护感或许带有某种幻觉,却反应了他们当时真实的心理依赖——一种寄托于“最高保护者”的信任。

但这种“庇护效应”本身便是脆弱的。胡耀邦虽身居总书记,却始终受制于元老政治的掣肘,他的开放姿态未能制度化,只能以个人意志维持。在这种背景下,《青年论坛》的生存状态恰恰体现了一种悖论:思想自由的空间建立在体制内开明者的支撑上,而一旦这支撑动摇,整个思想生态便瞬间坍塌。1987年1月胡耀邦被迫辞职后,《青年论坛》便被迫关闭,当时的文化热潮也接连受挫,正是这一悖论鲜明的注脚。

体制内外“共谋”的缝隙:胡德平与《青年论坛》的存续逻辑

如果说胡耀邦在北京的“宽厚宽松”姿态为思想界提供了象征性庇护,那么胡德平1984年4月之南下武汉,则是这种庇护的具象化。李明华在回忆中反复提到,若没有胡德平的到来,《青年论坛》很可能在1984年创刊之前就即胎死腹中。

胡德平的身份极为特殊:一方面,他是胡耀邦之子,以中组部、团中央下派巡视员的身份来武汉,带着体制内的合法性光环;另一方面,他又有知识人的文化认同,长期从事学术研究,性格宽厚,愿意与青年平等交流。这双重身份,使他天然成为体制内改革派与青年知识群体之间的“桥梁性人物”。

在武汉的日子里,胡德平不仅以巡视员的名义出席青联活动,还多次到《青年论坛》编辑部与青年作者对话。他对刊物的定位有一句意味深长的话:“青年人写的文章,不必句句符合文件精神,但一定要写出自己的真心话。”这话成了编者们的“定心丸”。在当时的政治氛围下,能得到这样一句“半公开”的承认,几乎等同于一张保护令。

更具体的是,在创办资金、行政批文与审稿风波上,胡德平也屡次出手斡旋。1985年初,《青年论坛》因经费告急面临停刊,他通过青联(指中华全国青年联合会)渠道为刊物争取到一笔“青年工作专项资金”。同年,一篇涉及政治改革的文章被上级宣传部门要求撤稿,他以巡视员身份出面协调,最终使文章得以保留在内部发行本中。这些插曲表明,《青年论坛》的存在从来不是“自发的自由”,而是仰仗体制有力人物的持续掩护。

然而,这种掩护恰恰揭示了制度裂缝的吊诡性:它既制造了短暂的思想空间,也凸显了空间的极端脆弱。正因《青年论坛》从未获得制度化身份,它的一切合法性都依赖于人际网络与个别保护者。一旦胡德平调离,刊物立即失去屏障。1987年胡耀邦下台后,这种依附更是顷刻间瓦解,最终导致杂志停刊。

此处不得不提的是,除了体制内政治人物对《青年论坛》的保护外,当时中国思想界老一辈著名学人的介入,也为这份刊物注入了精神上的合法性与文化上的承认。李明华在回忆录第三章《前辈的肩膀》中写到,青年人创办刊物,若没有“精神支点”,极易沦为稚嫩的自我表达;而正是李泽厚、章开沅、董辅礽等著名学者的公开寄语与默默支持,使得《青年论坛》不只是青年自娱的平台,而成为八十年代思想公共性的缩影。

“接通”却难以“转换”:知识实验的制度困境

1980年代,各种青年刊物如雨后春笋,与其它刊物不同,《青年论坛》不满足于纯粹的思想抒情或文化随笔,而是试图在学术性和理论性上有所突破。

李明华回忆,刊物在1984至1986年间陆续刊发了多篇译介和理论探讨文章,力图在体制允许的边界内推动知识更新。青年编辑们从国外期刊和港台出版物中择取论文,翻译有关“后实证主义”(postpositivism)、“人本马克思主义”(humanist Marxism)乃至“现代化理论”的片段,尝试将其转化为中国语境下的学术话语。

这种努力在当时具有先锋性。比如,《青年论坛》专门设立“国外思想动态”专栏,介绍哈贝马斯的“交往理性”、托夫勒的《第三次浪潮》,以及西方社会学关于“风险社会”的初步讨论。在武汉这样一座非政治中心城市,青年学人能接触到这些理论并公开发表,足见当时思想解放所带来的真实震荡。青年作者在文章中热切地追问:科学与人文能否重新整合?现代化是否必然伴随价值的失落?这些讨论,折射出他们试图将西方社会科学与中国转型经验“接通”的雄心。

然而,李明华也坦言,这种“接通”往往止步于译介和介绍。由于政治氛围限制,文章往往必须以“学习国外先进经验”和“为社会主义现代化服务”作为掩护,否则很难通过审查。结果是,原本可能引发深度反思的问题,只能以政策化的口吻“软着陆”。这种处理方式,使得“接通”与“转换”之间始终存在一道无法跨越的断层:知识被接通了,但制度并未被触动。

这一落差在几次具体事件中体现尤为明显。1985年,《青年论坛》编辑部曾计划翻译并连载一组西方政治学关于“分权制衡”的研究,但在报批过程中被明确要求删除涉及“多党制”和“议会监督”的内容,最后仅保留了关于“地方治理”的部分。青年编辑们无奈地笑称:“分权只剩下分工,制衡成了协调。”这种调侃背后,其实是深深的制度挫败感——他们知道知识的锋芒被钝化,而刊物也只能在自我阉割中求得存续。

另一例子是“经济体制改革”专题。当时青年作者试图引入西方经济学中的“市场效率”概念,讨论价格双轨制的弊端。但最终成稿时必须加入“社会主义优越性”的保证条款,以免触碰“姓社姓资”的意识形态警戒线。于是,一篇本可成为制度批判的文章,最后变成了“对政策的理论支持”。这种尴尬,正好映射出《青年论坛》的处境:它渴望推动思想的深度转换,却被迫成为体制合法性的学理附庸。

悖论下崩塌:胡耀邦的中道实验

如果说《青年论坛》代表的是体制边缘的知识试验田,那么胡耀邦则是来自体制核心圈的民间思想实验支持者。两者之间,恰恰构成了八十年代中国改革政治的“双重中道”:前者在思想上开掘空间,后者在制度上搭建支撑。但正是在这两条中道的交汇处,悖论开始显现。

胡耀邦晚年的政治轨迹,算是一部“中道”实验史。自1978年起,他以出人意料的速度完成了历史性转身:从“文革”中被整肃的边缘人物,成为拨乱反正的中坚力量。他的改革姿态不同于邓小平的战略务实主义,也有别于陈云的守成谨慎,而是一种颇具理想主义色彩的制度更新逻辑。他强调“解放思想”、“实事求是”,坚信通过宽松的政治氛围、鼓励青年参政和知识界发声,能够托举起体制的自我更新。

然而,悖论也随之而来,胡耀邦既是思想解放的保护伞,又是体制秩序的守护者。他一方面推动平反冤假错案,重启学术讨论,支持青年刊物的思想探索;另一方面,他又必须在集体领导的格局下为这些“越界”行为承担责任。当《青年论坛》以及其他青年思想社团不断试探边界时,胡耀邦既不愿打压,又无法公开庇护,只能以“宽容监督”的模糊策略处理。这种姿态,使他成为青年一代的精神支点,却也在高层政治中累积风险。

1986年底,当学潮兴起,青年知识分子和学生提出更多制度化诉求时,胡耀邦选择以温和姿态应对,他强调要倾听青年意见,提出“批评并不可怕”。但这一立场遭到保守派强烈攻击,甚至被指责为“放纵自由化”。最终,1987年初,他在舆论与政治的双重压力下被迫辞职。青年人普遍感到“背后靠山倒了”,而体制内部则松了一口气。胡耀邦的下台,标志着他中道实验的一次重大坍塌:他既没有成功转化青年力量为制度合力,也没有在党内守成力量中获得持久支撑。

本质上,胡耀邦对知识界和青年的保护,是依赖个人权威和政治地位来为他们遮风挡雨。然而,缺乏制度化的保障,这种托举只能是短期的、个体性的。一旦个人的政治资源耗尽,整个知识网络便失去依托。换言之,胡耀邦以个人道德与政治勇气,填补了制度未能提供的空间;但正因如此,他的倒台便意味着八十年代思想空间的塌陷——青年群体和体制改革力量在胡耀邦身上汇合,却也在他倒台的那一刻共同陷入困局。

回望八十年代,《青年论坛》与胡耀邦的政治实践宛如一组互文的寓言:一个代表体制外的思想实验,一个代表体制内的政治改革。二者看似处于不同空间,却在“中道”坐标上遥相呼应——都试图在激进与保守的两极之间,开辟一条温和、建设性的第三条道路。但这种尝试,最终显现出相似的困境。

今天回望,胡耀邦与《青年论坛》的交错命运,作为历史留下的一道未解方程,也可视作“未竟的中道”的历史寓言:它是一条不断被尝试、却始终未能制度化的道路,其价值不在于已实现的成就,而在于不断出现的可能性。正如胡耀邦倒台后,仍有后来者继承他的精神;正如《青年论坛》停刊后,其成员散落各地,至今仍在不同领域延续着八十年代的启蒙遗产。

未来可能的变革与再生,不应再仅仅寄望于个人的庇护或一代人的激情,而必须形成一套可复制、可持续的制度结构。在当下的全球政治语境中,回望八十年代的“未竟中道”,不仅是对胡耀邦和《青年论坛》的历史追忆,更是对今天整整一代人的启发。

(本文刊发时有删节。)

本期推荐档案:

《青年论坛》(中国民间档案馆已收藏全14期)

《八十年代的一束思想之光——〈青年论坛〉纪事》(壹嘉出版网站)

An Intellectual Beacon of the 1980s: The Intertwined Fates of Youth Forum and Hu Yaobang

By Xiao Shu

In the 1980s, Wuhan’s Youth Forum was an influential intellectual magazine, on par with Shanghai’s World Economic Herald. The two were collectively known as “the one newspaper and one magazine.” Both actively explored themes of freedom and democracy, touching on politically sensitive issues and playing a significant role in the intellectual enlightenment of the Chinese people. Their fates were equally unfortunate: World Economic Herald was completely shut down due to the 1989 pro-democracy protests, while Youth Forum was forced to cease publication during the 1987 Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaign. With their closure, two intellectual beacons of the eighties were extinguished.

More than 30 years later, Li Minghua, the former editor-in-chief of Youth Forum, published An Intellectual Beacon of the 1980s: A Chronicle of Youth Forum. His book offers a firsthand account documenting how Youth Forum survived within the crevices of China’s political system and how this collaboration between people both inside and outside the system was forced to a halt. At the same time, the close association between Hu Deping, the son of former General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Hu Yaobang, and Youth Forum began to be more widely known.

The Ideological Earthquake of the “Criterion of Truth” Debate

Following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 and the end of the Cultural Revolution, Chinese society once again plunged into confusion and fear in February 1977 with the issuance of the “Two Whatevers,” an official line upholding all of Mao’s past decisions and instructions. At that time, the historical evaluation of Mao remained politically taboo. However, it was within this environment that a tide of intellectual liberation began to stir.

In A Chronicle of Youth Forum, Li Minghua reflects on the ideological climate of the time. He argues that genuine intellectual liberation didn’t emerge from a vacuum but from the system’s own loosening structure. The Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee and the “Criterion of Truth” debate in 1978, along with the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party” in 1981, were like a series of earthquakes that created cracks in China’s political center, allowing the flames of free thought to burst forth.

Among these events, the “Criterion of Truth” debate was the most symbolic and impactful. This debate, supported by Deng Xiaoping, was both a scholarly discussion and an institutional power play. It broke through the verbal shackles of the “Two Whatevers” by asserting that “practice is the sole criterion for testing truth.”

However, this debate was never intended to truly challenge the power structure. The resulting intellectual openness had a dual nature: while it provided a legitimate window for intellectuals to rediscover the concept of the individual, it also remained dependent on the highest authority’s protection, lacking any institutional guarantees. The space for intellectual liberation thus became a gift bestowed by power—not a natural development of public politics, but a byproduct of crisis management.

This delicate situation shaped the unique rhythm of China’s intellectual life in the 1980s. The air of freedom was present but could disperse at any moment. The boundaries of thought expanded but were constantly being tested. As Li Minghua recalls, there was a nonlinear institutional rhythm of alternating openness and tightening. In fact, the brief flourishing of intellectual and cultural spheres in the early to mid-1980s, from the “literary craze” to the “cultural craze” and the rise of various youth publications, was directly linked to these structural cracks.

This was the context in which Youth Forum emerged as a product of the cracks. The bi-monthly magazine, led by the Hubei Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, was founded in Wuhan in August 1984. From its inaugural issue in November 1984 until its forced closure in 1987, Youth Forum published 14 issues, eight of which focused on the theme of freedom. One of the most important articles in the inaugural issue, “A Salute to Freedom” by Hu Deping, caused a sensation and was widely reprinted by official media. In its July and September 1986 issues, the magazine published Hu Ping’s long essay “On Freedom of Speech.” Following this, it published Min Qi’s “Freedom of the Press and Marx” and held a symposium called “Discussions with People from All Walks of Life in the Capital on ‘On Freedom of Speech.’”

Although the magazine advocated for freedom from its inception, Youth Forum had to survive by walking a tightrope on the edge of political taboos when selecting topics. For example, after the Communist Party launched the “Campaign to Eliminate Spiritual Pollution” in 1983, academics in Wuhan felt an atmosphere of high pressure, and the newly founded Youth Forum was not immune. In response, Li Minghua and his colleagues chose an indirect strategy. Instead of directly challenging the campaign, they published neutral topics like “Youth Development” and “University Student Thoughts,” preserving a sliver of breathing room for young people.

In late 1986, when the political tide of anti-bourgeois liberalization suddenly surged, Youth Forum again faced a crisis. The magazine had planned a special issue discussing “Youth and Future Responsibility,” with some authors attempting to include a call for political system reform. However, with the rapidly changing political climate, the issue was replaced with the safer theme of “Youth Literature and Aesthetics,” and the magazine’s masthead added the words: “In line with the Party’s rectification spirit.” This act of self-censorship and strategic compromise reveals how intellectual liberation was forced to align with the political rhythm: once the cracks closed, the space immediately collapsed.

These examples offer a glimpse into the true nature of intellectual liberation in the 1980s. It was neither a romanticized burst of freedom nor an act of dissidence outside the system. Instead, it was an institutional experiment that constantly adapted within the cracks of power. The editors of Youth Forum were not naive. They understood that the climate of freedom could end at any moment, so they constantly sought flexibility in their words, layout, and discourse. This combination of limited freedom and passive compromise constituted the core tension of intellectual liberation in the 1980s.

This breathing in the cracks was made possible largely because of Hu Yaobang. During the 1983 “Anti-Spiritual Pollution” campaign, Hu Yaobang said in a speech in Shanghai, “Don’t arbitrarily put labels on young people,” which provided a protective umbrella for cultural and youth publications. In 1985, he criticized the ideological control of the Central Propaganda Department at a central meeting, demanding “a little more tolerance for young people,” which directly influenced a series of liberalizing policies after the new propaganda minister, Zhu Houze, took office. Li Minghua recalls a saying that circulated among the magazine’s editors: “As long as Secretary Hu is here, the winds from Beijing won’t completely blow to Wuhan.” This sense of security, while perhaps an illusion, reflected their psychological dependence on a supreme protector.

However, this patronage was inherently fragile. Although Hu Yaobang was the General Secretary, he was always constrained by the politics of the Party elders. His open stance was never institutionalized and could only be maintained by his personal will. The survival of Youth Forum thus embodied a paradox: the space for intellectual freedom was built on the support of an enlightened figure within the system, and once this support wavered, the entire intellectual ecosystem instantly collapsed. After Hu Yaobang was forced to resign in January 1987, Youth Forum shut down, and the cultural tide of the 1980s began to recede.

The Survival Logic of Hu Deping and Youth Forum

If Hu Yaobang in Beijing provided symbolic protection for the intellectual community, then Hu Deping’s visit to Wuhan in April 1984 was the concrete manifestation of that protection. In his account, Li Minghua repeatedly mentions that without Hu Deping’s visit, Youth Forum likely would have been stillborn before it was founded in 1984.

Hu Deping’s identity was unique. On one hand, as Hu Yaobang’s son, he came to Wuhan as an inspector from the Central Organization Department and the Communist Youth League, carrying the legitimacy of the system. On the other hand, he had the cultural identity of an intellectual, having long been engaged in academic research. His tolerant nature made him willing to engage in open dialogue with young people. This dual identity naturally made him a bridge between reformists within the system and the young intellectual community.

During his time in Wuhan, Hu Deping not only attended youth league activities as an inspector but also visited the Youth Forum editorial office multiple times to talk with young authors. About the magazine’s purpose, he said: “The articles written by young people don’t have to strictly follow the spirit of official documents sentence by sentence, but they must express their genuine thoughts.” This statement became a source of reassurance for the editors. In the political climate of the time, receiving such approval was almost equivalent to a protective order.

More specifically, Hu Deping repeatedly intervened in matters of funding, administrative approval, and manuscript review. In early 1985, when Youth Forum faced closure due to a lack of funds, he used his connections with the All-China Youth Federation to secure a “special fund for youth work.” The same year, when a propaganda department demanded the withdrawal of an article on political reform, he intervened as an inspector, and the article was ultimately kept in the internally distributed version. These incidents show that the existence of Youth Forum was never a result of spontaneity and freedom but rather depended on the ongoing protection of influential figures within the system.

However, this protection also highlights the paradox of the cracks within the institutions: It created a temporary intellectual space but also exposed the extreme fragility of that space. Since Youth Forum never achieved institutionalized status, its legitimacy depended entirely on personal connections and individual protectors. Once Hu Deping was transferred, the magazine immediately lost its shield. After Hu Yaobang’s fall from power in 1987, this dependence instantly crumbled, ultimately leading to the magazine’s closure.

It is also worth noting that in addition to the protection from political figures, the involvement of prominent, senior Chinese academics at the time also provided the magazine with spiritual legitimacy and cultural recognition. In the third chapter of A Chronicle of Youth Forum, “On the Shoulders of Elders,” Li Minghua wrote that if a publication founded by young people lacks “spiritual support,” it can easily devolve into immature self-expression. It was the public messages and quiet support of renowned scholars like Li Zehou, Zhang Kaiyuan, and Dong Fureng that elevated Youth Forum from a platform for youthful self-expression to a microcosm of the intellectual public sphere in the eighties.

The Institutional Predicament of Intellectual Experiments

In the 1980s, various youth publications emerged, but Youth Forum stood out by not being content with mere intellectual lyricism or cultural essays. Instead, it sought to make breakthroughs in scholarship and theory.

Li Minghua recalls that between 1984 and 1986, the magazine published numerous translations and theoretical articles, attempting to promote intellectual renewal within the system’s acceptable boundaries. The young editors selected papers from foreign as well as Hong Kong and Taiwanese publications, translating fragments on topics such as postpositivism, humanist Marxism, and modernization theory. They tried to transform these concepts into academic discourse within the Chinese context.

This effort was pioneering at the time. For example, Youth Forum established a special column called “Foreign Intellectual Trends,” which introduced Habermas’s communicative rationality, Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave, and preliminary discussions in Western sociology about concepts such as the risk society. In a city like Wuhan, which was not a political center, the fact that young scholars could access and publicly publish these theories shows the impact of intellectual liberation at the time. The young authors passionately asked questions in their articles: Can science and the humanities be reintegrated? Does modernization inevitably lead to a loss of values? These discussions reflected their ambition to connect Western social sciences with China’s transformational experience.

However, Li Minghua also admitted that this connection often stopped at mere translation and introduction. Due to the restrictive political climate, articles had to be disguised as “learning from advanced foreign experiences” or “serving socialist modernization” to avoid censorship. As a result, questions that could have sparked deep reflection landed softly with policy-oriented language. This approach created a persistent gap between connecting and transforming: knowledge became connected, but the system remained untouched.

This gap was particularly evident in several specific incidents. In 1985, the Youth Forum editorial office planned to translate and serialize a series of Western political science studies on separation of powers as well as checks and balances. However, during the approval process, they were explicitly required to delete content related to multiparty systems and parliamentary oversight. Ultimately, only the parts about local governance were retained. The young editors jokingly remarked, “Separation of powers is now just a division of labor, and checks and balances have become mere coordination.” Behind this sarcasm was a deep sense of institutional frustration—they knew the intellectual edge had been blunted and that the magazine could only survive through self-censorship.

Another example was the special issue on economic system reform. The young authors attempted to introduce the concept of market efficiency from Western economics to discuss the problems with China’s dual-track pricing system (the coexistence of command economy with market economy). However, the final draft had to include a statement affirming “socialist superiority” to avoid the ideological red line of turning socialism into capitalism. An article that could have been a critique of the system ultimately became a theoretical support for policy. This awkward situation perfectly illustrates the predicament of Youth Forum: it longed to promote a deep transformation of thought but was forced to become a theoretical appendage of the system’s legitimacy.

The Collapse of a Paradox: Hu Yaobang’s Middle Way Experiment

If Youth Forum represented an intellectual testing ground on the periphery of the system, then Hu Yaobang was a supporter of civil intellectual experiments from the system’s core. Together, they constituted the “dual middle way” of China’s reform politics in the 1980s: one creating space for thought, the other building institutional support. Yet, it was at the intersection of these two middle ways that the paradox began to manifest.

Hu Yaobang’s political trajectory in his later years can be seen as a history of a “middle way” experiment. From 1978, he made a remarkable turn, going from a marginalized figure purged during the Cultural Revolution to a key force in the re-establishment of order. His reformist stance differed from Deng Xiaoping’s strategic pragmatism and Chen Yun’s conservative caution. Instead, it was an institutional renewal logic with a strong idealistic flavor. Hu emphasized “liberating the mind” and “seeking truth from facts,” firmly believing that a relaxed political atmosphere, encouraging youth to participate in politics, and allowing the intellectual community to speak out could support the system’s self-renewal.

However, a paradox also emerged. Hu Yaobang was both a protector of intellectual liberation and a guardian of the system’s order. While he promoted the rehabilitation of wrongly accused individuals, restarted academic discussions, and supported the intellectual explorations of youth publications, he also had to take responsibility within the collective leadership for these perceived transgressions against the establishment. As Youth Forum and other young intellectual groups continued to test the boundaries, Hu Yaobang was unwilling to suppress them but also unable to openly protect them. He could only manage the situation with a vague strategy of “tolerant supervision.” This stance made him a spiritual pillar for the younger generation, but it also accumulated risks in high-level politics.

In late 1986, when student protests arose and young intellectuals and students made more institutional demands, Hu Yaobang chose a mild approach, emphasizing the need to listen to young people and stating, “Criticism is not scary.” However, this position was fiercely attacked by conservatives and even accused of “condoning liberalization.” In early 1987, under both public and political pressure, Hu was forced to resign. Young people widely felt that their backer had fallen, while those within the system breathed a sigh of relief. Hu Yaobang’s downfall marked a major collapse of his middle-way experiment: he neither succeeded in transforming youth power into a cohesive institutional force nor gained lasting support from the Party’s conservative forces.

Looking back at the 1980s, the intertwined fates of Youth Forum and Hu Yaobang’s political practice serve as a pair of interwoven parables: one representing an intellectual experiment outside the system, the other a political reform within the system. They seemed to operate in different spheres but were deeply connected by their shared middle way—both sought to carve out a moderate and constructive path between the extremes of radicalism and conservatism. But this attempt ultimately ran into the same predicament.

Today, the intertwined fates of Hu Yaobang and Youth Forum remain an unsolved historical equation, a historical parable of an unfinished middle way. It is a path that was constantly attempted but never institutionalized. Its value lies not in what was achieved but in the possibilities that it presented. Just as there were those who inherited Hu Yaobang’s spirit after his fall, the members of Youth Forum scattered across the country after its closure, continuing the legacy of the enlightenment of the 1980s in various fields.

Any future change and regeneration should no longer rely solely on the protection of individuals or the passion of a single generation but must form a replicable and sustainable institutional structure. In the current global political context, reflecting on the unfinished middle way of the 1980s is not only a historical remembrance of Hu Yaobang and Youth Forum but also a source of inspiration for our generation today.

Recommended archives:

Youth Forum (China Unofficial Archives has collected all 14 issues for public viewing and download)

An Intellectual Beacon of the 1980s: A Chronicle of Youth Forum (Chinese version only; available from 1Plus Publishing)