贫瘠恶土中生长出的思想之花——遇罗克与《出身论》

The Flower of Thought That Blossomed in a Barren Wasteland: Yu Luoke and “On Class Origins”

作者:胡平

By Hu Ping

The English translation follows below.

距今整整59年前,正是1966年文革爆发不久后的“红八月”,一副“老子英雄儿好汉,老子反动儿混蛋”的对联横行一时。24岁的北京学徒工遇罗克写下长文《出身论》,向中共实行多年的阶级路线也即出身歧视政策,发起了最有力的挑战,在那个至暗的时代,发出了争取平等与人权的最强音。一个“黑五类”家庭出身的青年,用自己的思想和文字,竟然在当时造成了震动全国的效应。这是中共建政以来没有先例的。1968年1月,遇罗克被捕入狱。1970年3月5日,遇罗克被中共当局以“现行反革命”的罪名杀害,年仅27岁。

中共自1949年夺取政权后,就对它定义的阶级敌人(这个定义后来还不断扩大)实行严酷的镇压与剥夺,同时也对这些阶级敌人的子女实行种种歧视。按说,随着时间流逝,政权稳固,这种歧视应该逐渐弱化,但事实是,在进入1960年代后,中共对阶级敌人子女的歧视反而变得更严重。这一来是因为毛泽东在1962年提出“千万不要忘记阶级斗争”;第二个“拿不上台面”的原因,据我作为亲历者的感受,是因为我们那一代青少年和“红二代”是同一代人,大家都面临着升学、就业和社会地位的竞争。而“老革命们”发现,他们的子女在学习成绩等各个方面的表现都差强人意。共产党不好公开搞特权,于是祭出“阶级路线”这把尺子,把家庭出身当作首要评判标准,这就使得红二代在竞争中稳操胜券,中间家庭出身的子女倍受排挤,“阶级敌人”的子女则沦为最大的牺牲品。

现在的年轻人恐怕很难想象,在毛时代,出身歧视是何等的普遍,何等的严重,以及何等的荒谬。文革前,黑五类(地主、富农、反革命分子、坏分子、右派分子)子女就备受压抑。在贯彻阶级路线的名义下,黑五类子女更是处处遭受排挤,什么好事都轮不上——出身不好就是低人一等。

文革的爆发,更把这一切推向极端。1966年“红八月”,以红二代为主体的红卫兵在毛泽东的支持下登上政治舞台。红卫兵大力宣扬“无产阶级路线”,提出按家庭出身划分红五类(工人、贫农、革命干部、革命军人、革命烈士)和黑五类——后扩大为黑七类(增加了资本家和走资派)。

“老子英雄儿好汉,老子反动儿混蛋”的对联从而传遍全国,公然把出身黑五类的同学当作批判斗争的对象而百般羞辱打击,不少地方都有黑五类学生被打伤打死或被逼自杀。北京大兴县发生了持续5天的针对黑五类及其子女和亲属的大屠杀,杀死了地富及其子女和亲属共325人,最大的80岁,最小的才38天,有22户人家被杀绝。

但不久之后,因为毛泽东发动文革的目的是整“党内走资本主义道路的当权派”,因此红卫兵攻击黑五类子女有“转移斗争大方向”之嫌;又因为不少红二代自己的父母被批斗,他们对运动有抵触,变成了“保爹保妈派”,更不为伟大领袖所喜。1966年10月,中央文革小组组长陈伯达作报告,其中专门提到前述对联,批评这副对联是鼓吹“反动的血统论”。随着全国对这幅对联的批判,黑五类青年顿有解放之感。

1

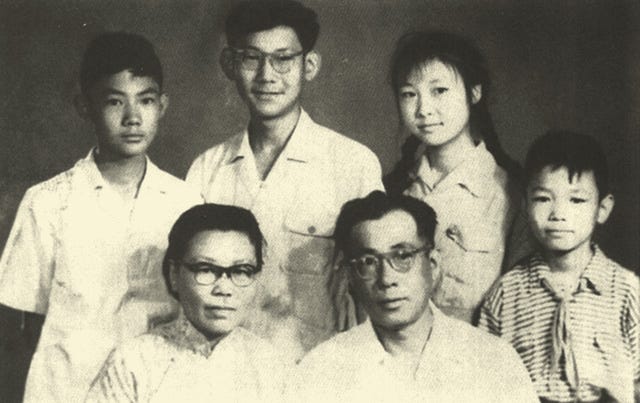

遇罗克1942年出生于北京,父母都曾经到日本留学。父亲遇崇基是工程师,母亲王秋琳是私营工厂厂长,父母都在1957年被打成右派分子。遇罗克品学兼优,于1960年参加高考,因为家庭出身未被录取。1962年,他又考了一次,仍然未被录取。遇罗克勤奋自学,关心天下大事,在1966年“红八月”最猖獗的时候,酝酿写作《出身论》。

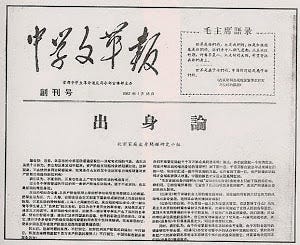

1966年10月,遇罗克的弟弟遇罗文和遇罗勉在广州把《出身论》油印了几百份到处散发。北京四中的高二学生牟志京在“红八月”最猖獗的时候就反对前述对联,读到《出身论》后如获至宝,立刻和遇家兄弟合作,创办了铅印小报《中学文革报》,创刊号出版于1967年1月18日,用整整三个版面全文发表了《出身论》,作者没有署名遇罗克,而是“北京家庭出身问题研究小组”。

《出身论》一问世,立刻在社会上引起强烈反响。此后,《中学文革报》又出版了6期,每期都有署名“北京家庭出身问题研究小组”也即遇罗克的大块文章。《中学文革报》在街头出售时,因买报的人太多,以至于要排长队,还要限量;来自全国各地的读者来信多到让邮递员无法递送,只好由遇罗文每天蹬着三轮车去邮局取。在小报与纪念章的交易市场上,《中学文革报》最珍贵,一份原来只卖两分钱的报卖到两元钱一份。在很多城市,都有人抄写张贴或翻印。

文革爆发那年,我就读于成都十九中,是高中66届,也就是1966年毕业。我的家庭属于黑五类,所以我对出身歧视的感受非常深。譬如1963年我初中毕业考高中,考试成绩在全市名列前茅,可是我报考的成都几个重点中学都不收我。我被分配到离家很远、教学质量在全市倒数一二的学校。在我准备考大学时,一位长者对我说:“以你的成绩,全国没有一个大学考不上;以你的家庭出身,全国没有一个大学会收你。”

1966年8月,那副对联也传到了成都。十九中的红卫兵组织了一场所谓阶级路线辩论会,实际上是批斗会。不少出身黑五类的同学被叫起来当众“承认自己是混蛋”。三天半的辩论会有差不多三天的时间是批判我。我对阶级路线有很多思考,所以一次又一次地上台发言,反驳对联。这次辩论会给我的巨大压力,永生难忘。

1967年2月初,我在一位外校同学的宿舍里,读到了载有《出身论》的《中学文革报》。感觉不像是在读别人的文章,而像是在读自己的思想。我饱受出身歧视之苦,有过和文章作者相似的经历和思考。我第一次发现在阶级路线的问题上还有别人和我想的完全一样,而且表述得那样严谨、清晰、深入与精辟。接下来,我和同学们商量,办起了一份小报——那是成都市中学生的第一份铅印小报,转载了署名“北京家庭出身问题研究小组”的文章。

2

《出身论》开篇第一句话写道:“家庭出身问题是长期以来严重的问题。”就是这样一句平实的陈述,遇罗克便把批评的锋芒不只局限于文革初期的那副对联,而且直截了当地指向当时的阶级路线。顺便一提,自陈伯达批判对联是血统论后,很多人也称其为血统论。但从理论上讲,对联的内容并不是血统论,因为它强调的不是先天的生物性遗传,而是强调后天的社会影响。在展开批评时,遇罗克先从分析对联入手,指出社会对一个人的影响大于家庭影响,这就驳倒了“老子反动儿混蛋”的“基本如此”。

接下来,作者着重讨论了“重在表现”问题,指出家庭出身和本人的阶级成份完全不是一回事,写道:“请问:出身不好,表现好,是不是可以抹杀人家的成绩?出身好,表现不好,是不是可以掩饰人家的缺点?出身不好,表现不好,是不是要罪加一等?出身好,表现好,是不是要夸大优点?难道这样做是有道理的吗?”

作者进一步指出:“既看出身,也看表现”,实际上不免要滑到“只看出身,不看表现”的泥坑里去。出身多么容易看,要看表现是何等麻烦;一般人图省事,也是图保险,自然倾向于重出身,轻表现,或者干脆只看出身,不看表现。

另外,针对把出身歧视说成是“考验”人的革命高调,作者反驳道:“收起你的考验吧……忘记了马克思的话吗?‘要求不幸者是完美无缺的’,那是多么不道德!”《出身论》还反驳了如下一种观点——“你们的爸爸压迫过我们的爸爸,所以我们现在对你们不客气!”这种观点极少见之于公开的文字,可却是许多出身歧视论者心照不宣的深层意识。作者特意挑明,从而把对方置于尴尬的境地。最后,文章号召“受压抑最深的青年”,“一切受反动势力迫害的革命青年”起来战斗,“胜利必将属于你们”。

《出身论》文辞风格清新文雅,在当年那种环境下堪称奇迹。和昔日名噪一时的各种雄文大作相比,仅从文风着眼,《出身论》也是鹤立鸡群。那时盛行的文风是浮夸、霸道、粗率、武断,唯《出身论》出淤泥而不染,朴素、平和、细致、缜密。

《出身论》的署名是“北京家庭出身问题研究小组”,既不是什么兵团、公社、战斗队、战斗组,也不叫“革命”、“造反”、“东方红”、“井冈山”,在当时别具一格。《出身论》的精彩之处不仅在于它的论点,更在于它的论证。文革中多的是以论点尖锐大胆著称的文章,遗憾的是,这些文章的论证大都粗疏单薄,乏善可陈。《出身论》则不然,它论证有力,且逻辑严谨,措辞准确,不但支持了作者的论点,也给读者更广泛的联想和启示。

然而,很快就从北京传来消息。1967年4月14日,中央文革小组成员戚本禹在接见首都中学红代会代表时发表讲话,批评《出身论》是大毒草。戚本禹说:“《出身论》是让人们不要阶级成份,否认阶级观点,用一种客观主义的观点、资产阶级的观点攻击社会主义,它实际上是宣扬彭真那一套,煽动青年反党。”

此前,我一直坚信,《出身论》是正确的,是符合毛泽东思想的,无懈可击。读到戚本禹的讲话,我既反感又恐惧。戚本禹说“《出身论》是让人们不要阶级成份”,这一望而知就是在混淆家庭出身与本人阶级成份的区别,而这种区别《出身论》早就讲得一清二楚。在戚本禹的讲话中,唯一令我困惑的是“客观主义”这个哲学概念。过去我们被教育说主观主义不对,怎么客观主义也不对呢?我很快就明白了这句话的弦外之音。戚本禹是间接地宣告:“我们共产党就是不会对我们的子女和黑五类的子女一视同仁,我们就是拒绝公平,我们就是要歧视你们黑五类子女。你不服吗?你不满吗?那就是反党反社会主义!”如前所说,从理论上讲,对联并不是血统论。但实际上,共产党的阶级路线就是血统论:对“敌人”的子女搞株连,给自家的孩子以特权。

1968年1月5日,当时正在撰写《工资论》的遇罗克被抄家和逮捕。此后两年中经过80多次“预审”,遇罗克被指控:“一九六三年以来,遇犯散布大量反动言论,书写数万字的反动信件、诗词和日记,恶毒地诬蔑诽谤无产阶级司令部;在无产阶级文化大革命中书写反动文章十余篇,印发全国各地,大造反革命舆论;还网罗本市与外地的反坏分子十余人,阴谋进行暗杀活动(这一条当然是无中生有——笔者注),妄图颠覆无产阶级专政。遇犯在押期间,反革命气焰仍很嚣张。”

1970年1月31日,中共中央发出《关于打击反革命破坏活动的指示》。3月5日,在北京市工人体育场召开的公判大会上,遇罗克被以现行反革命罪宣判死刑,立即执行 ,随后遭枪决,尚未满28岁。

3

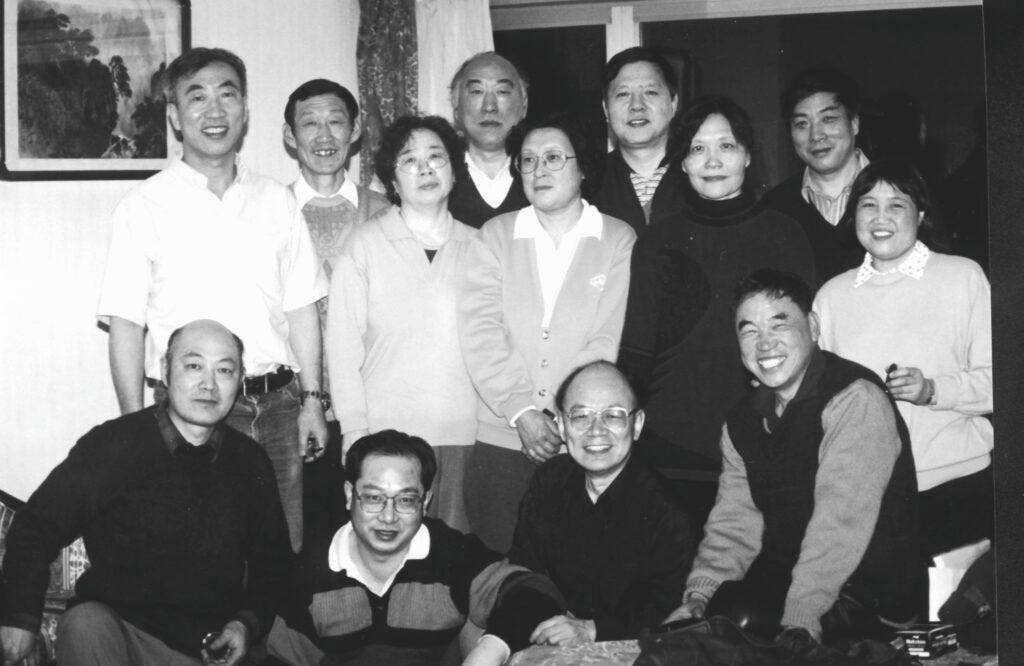

1976年9月9日,毛泽东死,10月6日,四人帮被抓。1978至1979年,北京兴起民主墙运动。民间刊物《四五论坛》、《今天》和《沃土》等率先发文纪念遇罗克。1979年11月,北京市中级人民法院下文为遇罗克平反。第二年夏天,官方刊物《新时期》和《光明日报》发表了关于遇罗克的长篇报导,称遇罗克为“逆风恶浪中的雄鹰”、“思想解放的先驱”、“划破夜幕的陨星”。

我始终相信,遇罗克被杀害,是因为他那非凡的勇气和智慧以及造成的巨大影响,引起了专制者发自内心的恐慌。那么是谁下令杀害遇罗克?作为研究者,本人多年来都在寻找答案。据友人Y君说,吴德(时任北京市革委会主任)之子曾亲口告诉他,是周恩来下令杀害遇罗克的。周恩来说:“这样的人不杀,杀谁?”

作为那个时代的亲历者,我个人认为这很有可能。首先,遇罗克的《出身论》影响遍及全国,对遇罗克的定案决不是北京市一级就能拍板的,很可能涉及中共最高层。1967年4月,戚本禹点名批判《出身论》,遇罗克1968年1月被捕,先是判15年监禁,后来突然又改成死刑,但并没有立刻执行,一直到1970年3月才被枪杀。从整个过程来看,具体主管部门好像没有准主意,抓不抓,判不判,怎么判,执不执行,好像都不是由他们做主,而是由更高层的大人物直接干预的结果。

下令杀害遇罗克的大人物不会是林彪、四人帮一伙。否则,当后来遇罗克在全国范围内被公开平反,还通过《光明日报》正面歌颂时,这早就揭露出来了。那时候,凡是能推到林彪、四人帮头上的坏事,一定会推到他们头上,哪里还会替他们遮掩?唯有下令杀害遇罗克的大人物属于中共在文革后、甚至在今天都必须维护其“崇高”声誉和“光辉”形象的,当局才会始终讳莫如深。

4

今天的年轻人,也许因为对那个时代的陌生,而不能对遇罗克和他的《出身论》给予充分的评价。

确实,《出身论》一文中,遇罗克频频引用了毛泽东语录,同时把所谓刘邓路线作为批判的箭靶。但如果把它放在当时的语境里,这并不一定表明作者的思想局限,而可能出于其斗争策略。要理解一部作品,我们务必要考虑到它当时的语境,以及作者论辩的对手、试图说服的对象——启蒙者必须善于因人施教。

今天的我们,或许不难以所谓更纯粹的人权观、平等观写出一篇似乎更彻底的《出身论》,但倘若把这样的文章放在当时的历史背景下,又有多少人能理解、能接受,并公开站出来支持拥护,从而形成一股不容忽视的抗争力量呢?也就是说,今天的我们要为当年的中国另写一篇《出身论》,只怕不可能比遇罗克写得更高明。可以说,遇罗克不仅拥有思想和勇气,而且还富有政治智慧。我并不是说他的思想没有局限性,而是惊讶和敬佩于在当年那样贫瘠恶劣的土地上,能生长出如此灿烂夺目的思想之花。你要知道当年的世界有多矮小,才能知道遇罗克的形象有多高大。

1968年秋,学校开始“清理阶级队伍”,我被工宣队、军宣队编入“学习班”受审查挨批判,那时给我加上了大大小小的许多问题。事后我才得知,我这次被清理就和当初办小报转载遇罗克的文章大有关联。只是他们查不出我和那个北京的“反革命组织”有什么联系,所以没有定下更严重的罪名。

1970年初夏,我在四川农村插队当知青时,一位朋友告诉我,《出身论》的作者遇罗克被当局以“现行反革命”的罪名杀害。我异常悲愤,从此记住了这个名字。

1978年秋,我考入北京大学,入学不久就参加了民主墙运动,成为民刊《沃土》之一员。我从若干新朋友,特别是民主墙的朋友那里知道了关于遇罗克的很多故事。1980年暑假,我探亲回到成都家中。这天,母亲拿出她收存的那份登有介绍遇罗克事迹的《光明日报》对我说:“要是你那时候在北京,恐怕也和他是一样的命运。”

那一年年底,在北京大学举行的自由竞选活动中,一批中文系同学向竞选者提出一份问答表,其中一个问题是“你现在最敬佩谁”,我毫不犹豫地写下“遇罗克”。

5

遇罗克既是那个时代的思想家,也是一个殉道者。他的道德勇气令人崇敬。

在监狱里,遇罗克受过多种折磨,但始终不屈服。和遇罗克一道关过死囚牢的张郎郎事后回忆道:在牢房中,大家都愁眉苦脸,遇罗克却始终笑眯眯的。当他们被狱方宣布关进死刑号时,所有人都被震惊了,脑子一片空白,甚至不是害怕,不是失常,而是一种愕然。唯有遇罗克像往日一般镇静,在向狱方大声说话时还带着微笑。

张郎郎说,遇罗克始终保持这种状态,一直到1970年3月5日被拉走枪毙,他的情绪一直非常稳定。在一次提审中,遇罗克依然以嘲弄的态度来对付,狱方使出最后一招,对遇罗克说,你想想还有什么最后的话想和家人说 ——这就是暗示要判遇罗克极刑了。狱方以为遇罗克会乱了方寸,但遇罗克只是静静地说:“我想要一支牙膏。”

遇罗克在1966年8月26日的日记里写道: “我想,假若我挨斗,我一定记住两件事:一、死不低头;二、开始坚强最后还坚强。”那时,他还没有发表《出身论》,可见他早就对可能遭遇的打击有充分的精神准备。在入狱前,遇罗克曾写过一首诗《赠友人》:

攻读健泳手足情,

遗业艰难赖众英。

未必清明牲壮鬼,

乾坤特重我头轻。

临刑的日子,张郎郎问遇罗克:“你为一篇《出身论》去死,值得吗?”遇罗克毫不犹豫地回答:“值得!”

遇罗克一案最后获得平反,中国固然走出了历史上最黑暗的时代,但并没有进入光明的时代。血统论即出身歧视虽然有所缓和,但并没有消除。一方面,我们还能看到权力的私相授受,“老子革命儿接班”,“还是自家的孩子靠得住”;另一方面,当局在迫害异议人士之余,也常常对亲属子女有所株连,体现出中国的人权状况仍然存在严重的问题。

2009年清明节,遇罗克雕像在北京通州宋庄美术馆落成。雕像正面镌刻着遇罗克的话:“任何通过个人努力所达不到的权力,我们一概不承认。”雕像底座上镌刻着北岛1980年献给遇罗克的诗句:“我并不是英雄,在没有英雄的年代里,我只想做一个人”。

在狱中,遇罗克给难友留下一句人生感言:“何为不朽?不朽在于引起后人的共鸣。”古人曰:人生三不朽,立德立言立功。遇罗克不朽。

作者胡平,《北京之春》荣誉主编。

本期推荐档案:

The Flower of Thought That Blossomed in a Barren Wasteland: Yu Luoke and “On Class Origins”

By Hu Ping

Exactly 59 years ago, in the “Red August” that followed the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, a couplet was everywhere in China: “If a father is a hero, then his son is a true man; if a father is a reactionary, then his son is a bastard.” Yu Luoke, a 24-year-old apprentice in Beijing, wrote a long article titled “On Class Origins” (also known in English as “On Family Background”). It was the most powerful challenge to the Chinese Communist Party’s long-standing policy of discrimination against people–including their children–who belonged to certain classes in society that the party defined as its enemies.

In that darkest of times, Yu raised a powerful voice for equality and human rights, shaking the entire country in a way not seen since the founding of the People’s Republic of China nearly two decades earlier. In January 1968, Yu was arrested and imprisoned. On March 5, 1970, the authorities executed him as a “counter-revolutionary,” at the age of 27.

Yu’s impact was all the more remarkable because he had been into a family belonging to one of the “five black categories” (heiwulei) of defined class enemies: landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, rightists, and a catch-all group known as bad elements. One might assume this discrimination would weaken as time passed and the authorities’ power became more secure. However, in the 1960s, discrimination against the children of class enemies actually grew more severe. This was partly because Mao Zedong, in 1962, called on everyone to “never forget class struggle.”

Another unofficial reason, as I recall from that time, was that my generation of young people and the “second-generation reds”—children of early communist revolutionaries and party members—were all competing for university admissions, jobs, and social status. The old revolutionaries discovered that their children’s academic performance and other abilities were disappointing. The Communist Party didn’t want to appear to be granting open privileges, so it used class differentiation—the “class line”—as a tool, making family background the primary criterion for evaluation. This ensured that the second-generation reds would win the competition. Children from ordinary families were sidelined, and the children of class enemies became the biggest victims.

It’s probably hard for young people today to imagine how widespread, serious, and absurd class-origin discrimination was during the Mao era. Before the Cultural Revolution, children from families belonging to the five black categories were already oppressed. Under the pretext of upholding the class line, these children were marginalized everywhere and were denied any good opportunities. A bad family background meant you were an inferior person.

The Cultural Revolution pushed this oppression to an extreme. In the Red August of 1966, with Mao Zedong’s support, Red Guards—primarily composed of second-generation reds—took the political stage. They aggressively promoted the “proletarian line,” proposing a division of people into “five red categories” (workers, poor peasants, revolutionary cadres, revolutionary soldiers, and revolutionary martyrs) and “five black categories” based on family background. The black categories were later expanded to seven, adding “capitalists” and “capitalist roaders.”

The couplet—“If a father is a hero, then his son is a true man; if a father is a reactionary, then his son is a bastard”—spread nationwide. It was used to openly criticize and humiliate classmates from families of the five black categories. In many places, students from these families were beaten, killed, or forced to commit suicide. In Daxing County, Beijing, a five-day massacre of families of the five black categories and their relatives occurred, resulting in 325 deaths. The oldest victim was 80, the youngest only 38 days old, and 22 families were completely wiped out.

However, things soon changed. Mao’s purpose for the Cultural Revolution was to attack “capitalist roaders in power within the Party,” so the Red Guards’ attacks on the children of the five black categories were seen as a distraction. Also, because many Red Guards’ own parents were being persecuted, they became resistant to the movement and were labeled the “dads-and-moms-protection faction,” which didn’t please Mao. In October 1966, Chen Boda, the head of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, gave a speech in which he specifically mentioned the couplet, criticizing it as promoting a “reactionary theory of bloodline.” As criticism of the couplet emerged nationwide, youths belonging to the five black categories felt liberated.

1

Yu Luoke was born in Beijing in 1942. Both of his parents had studied in Japan. His father Yu Chongji was an engineer, and his mother Wang Qiulin was a private factory manager. Both were labeled “rightists” in 1957. Yu was an excellent student, but he was not admitted to college after taking the entrance exam in 1960 due to his family background. He tried again in 1962 and was still not accepted. Yu continued to study diligently on his own and paid close attention to national affairs. He began writing “On Class Origins” during the peak of the couplet’s popularity in the “Red August” of 1966.

In October 1966, his younger brothers, Yu Luowen and Yu Luomian, mimeographed several hundred copies of “On Class Origins” and distributed them in Guangzhou. Mou Zhijing, a second-year high school student at Beijing No. 4 High School (a prominent school that many second-generation reds attended) who had opposed the couplet during “Red August,” read “On Class Origins” and cherished it. He immediately worked with the Yu brothers to start a printed tabloid called Middle School Cultural Revolution News. The first issue, published on January 18, 1967, printed the full three-page text of “On Class Origins,” crediting it to the “Beijing Research Group on Family Background Issues” instead of Yu Luoke.

The article immediately sparked a strong reaction in Chinese society. Middle School Cultural Revolution News went on to publish six more issues, each containing a long article by Yu Luoke with credits going to the “Beijing Research Group on Family Background Issues.” When the tabloid was sold on the streets, the lines of people waiting to buy it were so long that sales had to be limited. The number of letters from readers across the country was so great that mail carriers couldn’t deliver them all; Yu Luowen had to pick them up from the post office every day with a tricycle. The tabloid became a valuable collectible, with a two-cent copy selling for as much as two yuan. In many cities, people copied, posted, or reprinted it.

I was in the graduating class of 1966 at Chengdu No. 19 Middle School when the Cultural Revolution broke out. My family belonged to one of the five black categories, and I felt the sting of discrimination deeply. For example, when I graduated from middle school in 1963 and took the high school entrance exam, my scores were among the top in the city, but none of the top high schools in Chengdu I applied to accepted me. I was assigned to a school far from home, with one of the lowest teaching standards in the city. When I was preparing for college, an elder told me, “With your scores, you could get into any university in the country; but with your family background, no university will accept you.”

In August 1966, the couplet reached Chengdu. The Red Guards at my school organized a so-called “class line” debate, which was really just a criticism session. Many classmates belonging to the five black categories were called up to publicly admit they were “bastards.” For about three days of the three-and-a-half-day debate, I was the main target of criticism. I had thought a lot about the class line, so I went on stage repeatedly to refute the couplet. The immense pressure of that debate would be unforgettable for the rest of my life.

In early February 1967, in a classmate’s dorm room at another school, I read the issue of Middle School Cultural Revolution News that contained “On Class Origins.” I felt like I was reading my own thoughts. I had suffered greatly from discrimination and had similar experiences and ideas as the author. For the first time, I realized that someone else felt the same way I did about the class line, and had expressed it so precisely, clearly, and profoundly. My classmates and I then decided to start a tabloid—the first printed tabloid for high school students in Chengdu—to reprint the article credited to the “Beijing Research Group on Family Background Issues.”

2

The first sentence of “On Class Origins” reads: “The issue of family background has been a longstanding, serious social problem.” With this simple statement, Yu Luoke’s criticism was aimed not just at the couplet, but directly at the class line. (By the way, after Chen Boda criticized the couplet as a theory of bloodline, many people called it that. But theoretically, the couplet’s content isn’t a theory of bloodline because it emphasizes social influence rather than innate biological inheritance.) In his critique, Yu first analyzed the couplet, pointing out that social influence on a person is greater than family influence, which refuted the idea that “if a father is a reactionary, then his son is a bastard.”

Next, Yu focused on the importance of “performance.” He pointed out that family background and a person’s class status are completely different things, writing, “If I may ask: If a person has a bad background but performs well, can we dismiss their achievements? If a person has a good background but performs poorly, can we excuse their shortcomings? If a person has a bad background and performs poorly, should their sins be compounded? If a person has a good background and performs well, should their virtues be exaggerated? Is it reasonable to do so?”

Yu further pointed out that “looking at both background and performance” inevitably leads to the slippery slope of “only looking at background and not performance.” A person’s background is easy to see, but their performance is not. People naturally favor the easier and safer option, tending to emphasize background over performance, or simply ignoring performance altogether.

Furthermore, in response to the revolutionary rhetoric that framed class discrimination as a test of revolutionary zeal, Yu retorted, “Put away your tests... Have you forgotten Marx’s words? To demand perfection from the unfortunate is immoral!” “On Class Origins” also refuted the view that “your fathers oppressed our fathers, so we will not be kind to you now!” This idea was rarely expressed in public writings, but it was the deep, unspoken belief of many who advocated for class discrimination. Yu deliberately brought it to light, putting his opponents in an awkward position. Finally, “On Class Origins” called on the “most oppressed young people” and “all revolutionary youths persecuted by reactionary forces” to fight, declaring that “victory will surely belong to you.”

The writing style of “On Class Origins” was fresh and elegant. Compared to the popular essays of the time, the article’s style stood out. The prevailing style then was exaggerated, arrogant, coarse, and dogmatic, but “On Class Origins” was not influenced by the grandiose style. It was simple, calm, detailed, and rigorous.

The article’s byline, “Beijing Research Group on Family Background Issues,” was unique, as it wasn’t a “regiment,” a “commune,” or a “combat group,” as was common during the Cultural Revolution, nor did it have a revolutionary name like “Revolution,” “Rebels,” “The East is Red,” or “Jinggangshan.” The brilliance of “On Class Origins” lies not only in its arguments but also in its powerful and well-reasoned logic. Many articles during the Cultural Revolution were known for their daring arguments, but their reasoning was often perfunctory and uninspiring. “On Class Origins” was different; its logical, precise, and powerful arguments not only supported the author’s points but also offered readers a wider perspective and inspiration.

However, news from Beijing soon arrived. On April 14, 1967, Qi Benyu, a member of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, gave a speech to representatives of the Beijing Red Guard Congress, criticizing “On Class Origins” as a “big poisonous weed.” Qi Benyu claimed, “‘On Class Origins’ tells people to ignore class status, denies the class viewpoint, and uses an objectivist and bourgeois viewpoint to attack socialism. It is actually promoting Peng Zhen’s ideas and inciting youth to oppose the Party.”

Before this, I had firmly believed that “On Class Origins” was correct and in line with Mao Zedong Thought, completely beyond criticism. Reading Qi Benyu’s speech, I felt both disgust and fear. Qi Benyu said that “‘On Class Origins’ tells people to ignore class status,” which was a clear attempt to distort the distinction between family background and a person’s class status—a distinction the article had already made very clear.

The only part of Qi Benyu’s speech that confused me was the philosophical term “objectivism.” We had been taught that subjectivism was wrong, so why was objectivism also wrong? I soon understood the subtext: Qi Benyu was indirectly declaring: “We Communists will not treat our children and the children of the five black categories equally. We reject fairness. We will discriminate against you, the children of the five black categories. If you don’t accept this, if you are unhappy, you are anti-Party and anti-socialist!” As mentioned before, although the couplet wasn’t theoretically a theory of bloodline, the Communist Party’s class line was exactly that: guilt by association for the children of “enemies” and special privileges for their own children.

On January 5, 1968, Yu Luoke, who was then writing “On Wages”, had his home searched and was arrested. After more than 80 preliminary interrogations over the next two years, the accusation against him read in part: “Since 1963, the criminal Yu has spread a large amount of reactionary rhetoric, written tens of thousands of words of reactionary letters, poems, and diaries, and viciously slandered the proletarian headquarters. In the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, he wrote more than ten reactionary articles, which were printed and distributed nationwide, creating counter-revolutionary public opinion. He also roped in more than a dozen counter-revolutionaries and bad elements from Beijing and other places to plot assassination activities (this was, of course, a fabrication—author’s note) in an attempt to subvert the dictatorship of the proletariat. While in custody, the criminal Yu’s counter-revolutionary arrogance remained very high.”

On January 31, 1970, the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee issued the “Instruction on Cracking Down on Counter-Revolutionary Sabotage Activities.” On March 5, at a public sentencing rally at the Beijing Workers’ Stadium, Yu Luoke was sentenced to death as a “current counter-revolutionary” and immediately executed. He was not yet 28 years old.

3

On September 9, 1976, Mao Zedong died. On October 6, the Gang of Four was arrested. From 1978 to 1979, the Democracy Wall movement emerged in Beijing. Unofficial publications such as April 5th Forum, Today, and Fertile Soil were the first to publish articles commemorating Yu Luoke. In November 1979, the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court issued a document rehabilitating Yu. The following summer, official publications New Era and Guangming Daily published long reports about him, calling him “an eagle against the headwinds and evil waves,” “a pioneer of ideological liberation,” and “a meteor that pierced the night.”

I have always believed that Yu Luoke was killed because his extraordinary courage, wisdom, and enormous influence had caused the dictators to feel genuine panic. So who ordered his killing? As a researcher, I have been searching for the answer for many years. According to a friend, Mr. Y, Wu De’s (then head of the Beijing Revolutionary Committee) son told him personally that it was Zhou Enlai who ordered Yu’s execution. Zhou Enlai reportedly said, “If we don’t kill a person like this, who should we kill?”

As a witness of that era, I think this is very likely. First, “On Class Origins” had a nationwide impact, so the decision in Yu’s case could not have been made at the Beijing municipal level; it most likely involved the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party. In April 1967, Qi Benyu publicly criticized the article. Yu was arrested in January 1968 and initially sentenced to 15 years in prison, but this was suddenly changed to a death sentence. However, he wasn’t executed immediately; he was shot in March 1970. The entire process suggests that the lower government departments were unsure what to do. The decisions of whether to arrest, whether to sentence, how to sentence, and whether to execute seem to have been a result of direct intervention by a higher-level figure.

The high-level figure who ordered the execution would not have been Lin Biao or the Gang of Four. Otherwise, when Yu was later publicly rehabilitated nationwide and celebrated by Guangming Daily, it would have been exposed long ago. At that time, any bad deed that could be blamed on Lin Biao and the Gang of Four would have been attributed to them. There would have been no reason to cover for them. The only reason the authorities have always been so secretive about Yu’s death is that the high-level figure who ordered his execution is someone whose lofty reputation and glorious image the Communist Party had to protect after the Cultural Revolution, and even today.

4

Young people today, perhaps because they are unfamiliar with that era, may not fully appreciate Yu Luoke and his “On Class Origins.”

It is true that in the article, Yu frequently quoted Mao Zedong’s sayings and targeted the so-called Liu-Deng line for criticism. But when viewed in its historical context, this does not necessarily show a limitation in his thinking, but perhaps rather a strategic approach. To understand a work, we must consider its context, its intended audience, and the opponents the author was trying to persuade. An enlightener must be skilled at teaching in a way that people can learn.

Today, we might not find it difficult to write an “On Class Origins” that seems more complete, using concepts of human rights and equality. But if such an article were put into that historical context, how many people would have understood, accepted, and publicly supported it, thus forming a significant force of resistance? In other words, if we were to rewrite “On Class Origins” for China back then, it’s unlikely we could do a better job than Yu did. He was not only courageous and brilliant but also politically shrewd. I am not saying his ideas had no limitations, but I am filled with admiration that such a brilliant flower of thought could grow in such barren and harsh soil. You have to understand how small the world was back then to grasp how great Yu Luoke was.

In the autumn of 1968, the school began “clearing class ranks.” I was put into a “study class” by the Workers’ Propaganda Team and Military Propaganda Team to be interrogated and criticized. I was accused of many things. I later learned that this was closely related to my having started a tabloid to reprint “On Class Origins.” They couldn’t prove a link between me and that “counter-revolutionary organization” in Beijing, so they did not charge me with a more serious crime.

In the early summer of 1970, while I was a sent-down youth in a Sichuan village, a friend told me that the author of “On Class Origins,” Yu Luoke, had been executed by the authorities as a “counter-revolutionary.” I was furious and heartbroken, and I remembered his name forever.

In the autumn of 1978, I was admitted to Peking University and soon participated in the Democracy Wall movement, becoming a member of the unofficial publication Fertile Soil. From new friends, especially those from the Democracy Wall, I learned many stories about Yu Luoke. In the summer of 1980, I went home to Chengdu for a family visit. My mother took out the Guangming Daily she had saved, which reported on Yu Luoke’s deeds, and said to me, “If you had been in Beijing back then, you would probably have had the same fate as him.”

At the end of that year, in a democratic election campaign at Peking University, a group of students from the Chinese literature department gave candidates a questionnaire. One question asked, “Who do you admire the most now?” I wrote down “Yu Luoke” without hesitation.

5

Yu Luoke was both a thinker and a martyr of that era. His moral courage is inspiring.

In prison, Yu endured various forms of torture, but he never gave in. Zhang Langlang, who was in the death row cell with Yu, later recalled that while everyone else in the cell was anxious and worried, Yu always had a smile on his face. When the prison authorities announced they were being moved to death row, everyone was stunned, their minds blank. It wasn’t fear or madness, but a kind of daze. Only Yu remained as calm as ever, even smiling as he spoke loudly to the guards.

Zhang Langlang said that Yu maintained this state until he was taken away to be shot on March 5, 1970. His emotions were incredibly stable. During one interrogation, Yu’s mocking attitude persisted. The guards used a final tactic, telling him to think about what he wanted to say to his family—a clear hint that he was about to be executed. The guards expected Yu to lose his composure, but he just said quietly, “I want a tube of toothpaste.”

In his diary on August 26, 1966, Yu wrote, “I think, if I am ever persecuted, I must remember two things. One: do not bow my head. Two: stay strong from the beginning to the end.” At that time, he had not yet published “On Class Origins,” showing that he was already mentally prepared for the potential consequences. Before his imprisonment, Yu had written a poem titled “To a Friend”:

“Reading, swimming, a brotherhood’s bond;

A cause so tough, on heroes we depend.

The pure and bright may not sacrifice the strong;

The universe weighs, while my head is light.”

On the day of his execution, Zhang Langlang asked him, “Is it worth it to die for writing ‘On Class Origins’?” Yu answered without hesitation: “It is worth it!”

Yu Luoke’s case was eventually rehabilitated. China has moved out of its darkest period, but it has not entered a bright era. The theory of bloodline—class-origin discrimination—has been somewhat alleviated but not eliminated. On one hand, we can still see power being passed down privately, with “the father is a revolutionary and the son is the successor,” and the idea that “one’s own children are the most trustworthy.” On the other hand, while persecuting dissidents, the authorities often implicate their relatives and children, reflecting serious issues with China’s human rights situation.

On the Qingming Festival in 2009, a statue of Yu Luoke was unveiled at the Songzhuang Art Museum in Tongzhou, Beijing. The front is engraved with Yu’s words: “We do not recognize any power that cannot be achieved through personal effort.” The base of the statue is engraved with Bei Dao’s poem dedicated to Yu Luoke in 1980: “I am not a hero. In an age without heroes, I just want to be a person.”

In prison, Yu Luoke left a final reflection for a fellow inmate: “What is immortality? Immortality is to resonate with future generations.” The ancients said: there are three kinds of immortality in life: establishing virtue, establishing words, and establishing achievements. Yu Luoke is immortal.

Hu Ping is the honorary editor-in-chief of Beijing Spring.

Recommended archive:

Yu Luoke: “On Class Origins” (also known as “On Family Background” in English) (English version available)

Thank you so much. I can't tell you how important it is to me to have the opportunity to read this.

It is good to see a few others are coming here and witnessing the Crimes Against Humanity committed by the Chinese Communist Party from Mao to Xi.

And the comment by Leo below is heartening as more need to be made aware of these Crimes.

For a cataloging of some of these Crimes go here and pass it on:

MUSEUM OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY BY THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY (CCP) MAO TO XI

Holding Ideologues Aiding and Abetting the CCP Morally Accountable

https://responsiblyfree.substack.com/p/museum-of-crimes-against-humanity