中国走线客的背后:压力、断裂与个体选择

The Life Stories of China’s “Line-Walkers”—Pressures, Fractures, and Individual Choices

作者:林世钰

By Lin Shiyu

The English translation follows below.

二者似乎存在于平行宇宙中——2021年7月1日,中共中央总书记、中国国家主席习近平在北京宣告:“在中华大地上全面建成了小康社会”,会场上一片掌声;与之相对应,一个颇为尴尬的数据随即而来:2022年,从中国“走线(Walk the line)”(通常指通过中南美洲穿过美墨边境)到美国寻求庇护并滞留的人数,从前一年的342人,飙升到了1947人。2023年,这个数字超过了2.4万人,超过了过去十年穿越美国南部国境而被拘留的中国人总和。到2024年,这个数字还在增长。

生活在一个看上去如此繁荣昌盛的国家,为什么一些中国人愿意放弃肉眼可见的“幸福生活”,冒着命悬一线的风险,奔赴一个陌生的国家和不可知的未来?2022年,当身在纽约的我,第一次知道中国走线客的故事时,内心就升腾起这个大大的疑问。

1

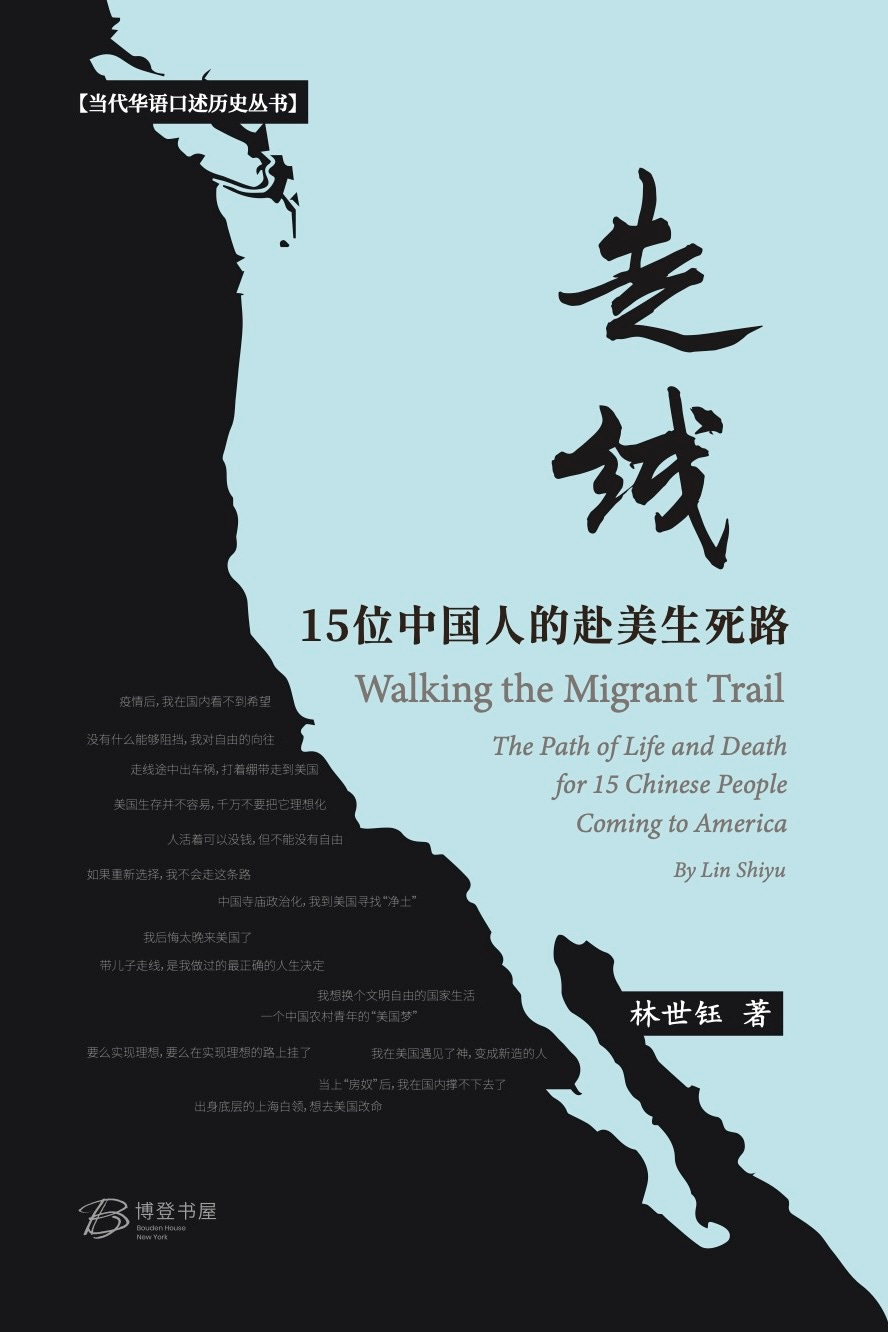

出于一个前媒体人的职业惯性,从2023年9月开始,我采访了19名走线客。并在两年后,出版了《走线:15位中国人的赴美生死路》一书。

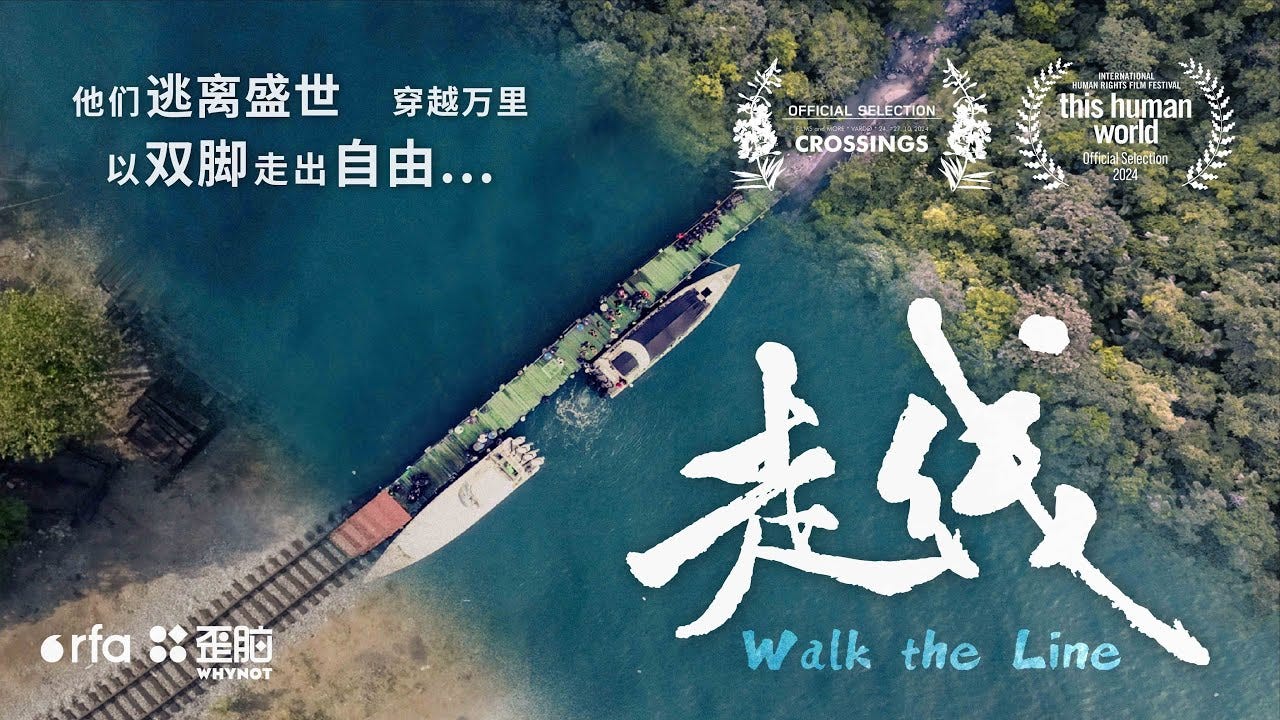

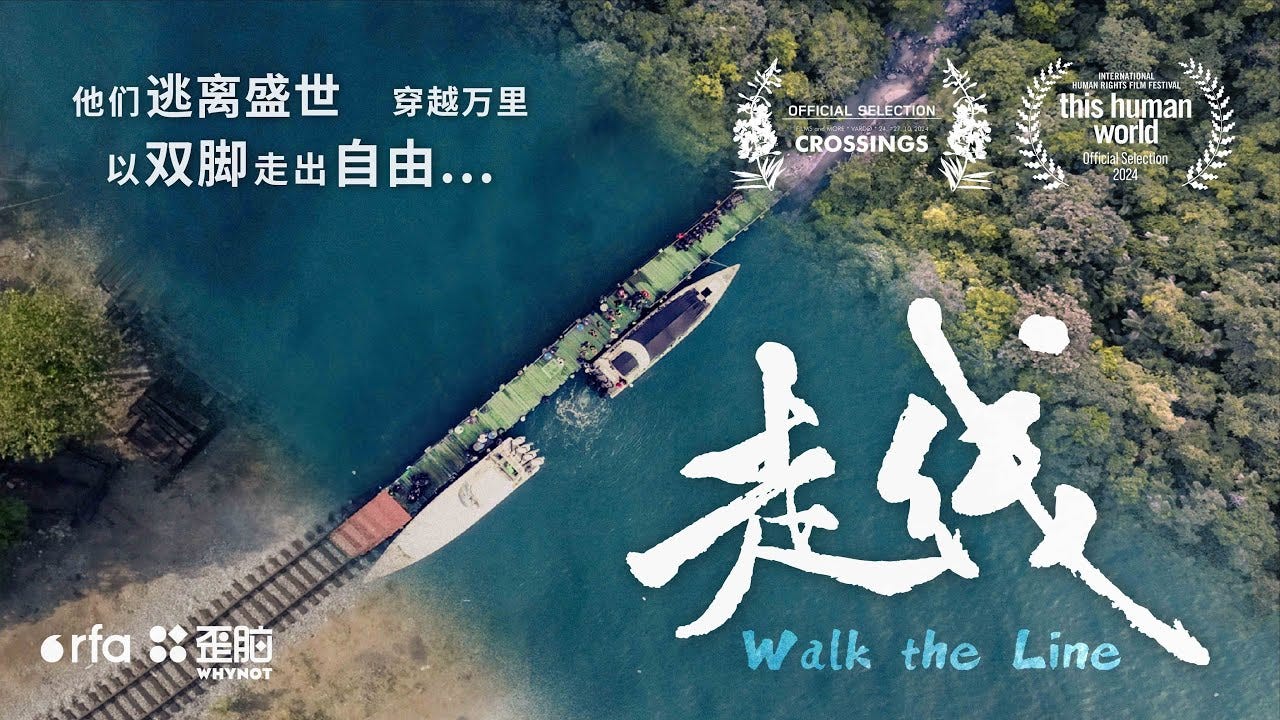

走线是一个跨文化、跨国境的复杂议题,涉及人权、社会正义、移民政策、文化冲突、中美关系、人类命运等各个范畴。此前,包括美国之音、自由亚洲电台、《纽约时报》、《华盛顿邮报》、BBC在内的主流媒体都报道过走线这一现象。其中,自由亚洲电台旗下的青年华语网络平台歪脑(WhyNot)就制作了深度纪录片《走线》(Walk the Line),记录了中国人走线的艰难历程。

作为一个习惯文字表达的前记者,我试图用深度访谈这个长焦镜的方式,聚焦15位中国走线客在中美两国的命运沉浮和生活辗转,呈现故土离散、文化冲突、身份悬浮等与政治学、社会学与人类学相关的内涵。在采访过程中,我努力爬梳走线客的命运主线——是什么推动他们一步步做出这种破釜沉舟的选择?我也在寻找那个改变他们命运的节点——那根压垮他们的最后一根稻草,究竟是什么?最后,我把他们出走的动因归结为三个词汇:food(食物);freedom(自由);follow(追随)。

在我看来,food可以泛指广义上的经济生活。中国疫情三年严苛的清零政策,导致中国经济江河日下,小企业主破产,房地产市场崩盘,百业凋零,民生凋敝。经济上的巨大压力是大部分受访者选择走线离开中国最主要的原因。

比如我采访的刘成,一个在广州开挖掘机的小伙子,贷款买了两套房子,变成“房奴”(指背巨额房屋贷款的人)。新冠疫情后,中国房地产行业崩盘,他收入陡降,无法支撑现有生活。不得已,夫妻两人走线到美国。“如果还待在国内,我估计早就自杀了。”他告诉我。

在我采访的人中,只有少数人是为了freedom(自由)而走线到美国。过去十几年,中国加强对意识形态的控制,言论空间日益缩紧,公民社会几近消亡,一些维权人士、异见人士和宗教人士受到打压。这对部分觉醒者来说,是很难忍受的一段“历史垃圾时间”。他们中的一些人,为了追求民主自由,走线来到美国。

我采访的两个年轻人,就属于这种情况。其中一个叫Steven Lau的90后,来美国前在物流行业工作,月收入多达2万到4万人民币。一次偶然的机会,他翻墙(通过使用VPN穿越防火墙)看到了土改、反右、文革、八九六四等在国内被长期遮蔽的历史,想与亲人和朋友分享,却发现这些是政治禁忌。他为了追寻历史真相,走线到了美国。

还有一些人认为走线是一种社会风潮,是一件很酷的事情,所以follow(追随)别人,他们大多都是随大流的心态。但这些人由于没有足够的思想准备,无法忍受美国生活的艰辛,后来大部分都返回了中国。

2

在采访和写作中,我希望摒弃那些传统的成功学式的移民叙事方法,呈现这15位受访者在美国的真实生活状态。这些受访者的人生,以及他们的美国梦各有不同——有人因错过早年的最佳出国时机而感到后悔;有人在走线途中遭遇了车祸却坚持前行;有人很快适应了美国生活,认为“美国不是天堂,但最接近天堂”;有人则后悔来美国,因为“在美国谋生,并没有想象中容易”,“如果重新选择,不会走这条路”;有人则选择了默默回国。

这些走线客冒着生命危险进入美国的时候,往往并不知道自己接下来要面对什么。他们即将面对的不止是美国光鲜的A面——世界第一强国的显赫地位、购买力强劲的美元、相对安全的食品药品和尊重孩子个性的教育体系;同时亦有阴暗的B面——僵化的移民体系、冷酷的政客、两极分化的政治、部分反智的乌合之众、昂贵的医疗等等……特别是川普再次上台后,随着对移民充满敌意的政策屡屡出台,他们的生存困境也日益加剧。本书中的一些受访者,为了躲避ICE(美国联邦移民与海关执法局)的抓捕,已经换了好几份工作,终日生活在惶恐之中。

我想告诉读者的是一个基本的现实:对很多人来说,抵达美国并不等于到达幸福的终点。相反,它可能是艰难生活的开端,身份困境、法律风险、谋生艰难和精神孤独仍在延续。这对潜在移民者具有现实警示意义,也避免他们将危险的路径浪漫化。

写作此书时,我努力让宏大的移民议题重新回到人本身的尺度上。一直以来,走线客掉进两种文化的罅隙中,面目模糊。在美国的公共语境中,走线客往往被简化为数字、政策问题或道德争议对象,一些美国政客动辄将非法移民作为攫取权力或攻击对手的棋子,将此议题政治化、党派化,鲜有人把他们当作活生生的人,从人的角度关注他们、研究他们。

我和走线客来美路径虽然殊异,但我们有一个共同身份——外来者,这使我在某种程度上容易与之共情。所以写作此书时,我不想预设任何立场,只想把他们还原为有情感、有温度的个人,恢复他们作为丈夫、父亲、儿子或者妻子、母亲、女儿的身份。让模糊的面孔被清晰呈现,让沉默的故事被听见。这样,读者可以从对与错、合法与非法的二元思维中跳脱出来,转向更深层次的对人的境况的思考——他们的人生究竟经历了什么,为什么如此选择?

3

为什么选择口述实录这种纯客观的叙事方式?因为我不想给出自己的价值裁决,而是把判断权交给读者:在生存、安全、尊严与规则之间,人究竟如何选择,能走多远?它提供的不是结论,而是一组难以被忽视的经验事实。这些事实提醒研究者:任何关于移民治理、风险控制或制度设计的讨论,若无法回应这些处于制度边缘的具体人生,理论本身也将失去现实解释力。

正如美国加州大学洛杉矶分校人类学教授杰森·德莱昂在其新作《移民路上的生与死:美墨边境人类学实录》序言中所说,“唯有听见他们的声音和看到他们的脸,才能感受到他们是活生生的人。唯有将他们还原为‘人’,我们才能认真讨论如何解决美国千疮百孔的移民制度。”

最近,美国ICE肆意抓捕非法移民,明尼苏达州甚至发生两起ICE枪杀美国公民事件,导致民众强烈抗议。这再次引发了人们对美国移民制度的深度思考:如何建立有效的社会对话机制,对移民政策进行调整和改进,平衡非法移民的合法权益和国家安全之间的矛盾,使非法移民群体不致成为政治冲突的牺牲品?

在采访写作中,我把采访重点转向走线客们“离开中国的那个节点”,也就是,他们“为什么非走不可”?这些中国走线客离开原生国家,穿越危险的南美洲和中美洲,面对随时可能发生的暴力、疾病和死亡,而到达一个语言、文化和社会体系与原生国家迥异的国度,这种把自己置于死地而后生的勇气,其背后的动因反映了当代中国社会的深刻变化,彰显了所谓繁荣中国的另一面。

这是一个结构性问题,而不只是个人命运。15位中国人为什么做出走线选择,不单因为经济困境、个人冲动,他们基本上都谈及的一个原因是——“在中国看不到希望”。这背后有制度、阶层流动受阻、家庭责任、代际焦虑,以及全球移民体系本身的残酷性。我试图让读者知道,走线不是少数人的极端行为,而是多重社会结构挤压下的结果,它真实呈现了中国社会贫富差距扩大、折叠化的现状。

在我看来,每个走线者犹如一片片拼图,通过这些拼图,我们大致可以拼凑出一幅当下中国的真实图像,观察到中国民众真实的生活光景——他们究竟是强国富民,还是盛世蝼蚁?

可以说,本书更接近一部当代中国社会的切片,而不仅是美国移民故事。作为本书作者,我冀望这本没有任何畅销书特质的书未来具有档案价值——如果人们回看这一时期,中国社会的压力、断裂与个体选择,都可以在这些人物故事中找到线索。

本期推荐档案:

《歪脑》杂志:《走线》纪录片

The Life Stories of China’s “Line-Walkers”—Pressures, Fractures, and Individual Choices

By Lin Shiyu

Two realities seem to exist in parallel universes. On July 1, 2021, Xi Jinping declared in Beijing: “We have built a moderately prosperous society in all respects on the land of China,” a statement met with thunderous applause. Conversely, a rather inconvenient statistic soon emerged: in 2022, the number of people from China who “walked the line” (referring to entering the United States via the southern border after traveling through Central and South America) to seek asylum and remain in the U.S. soared from 342 the previous year to 1,947. In 2023, this number exceeded 24,000, surpassing the total number of Chinese nationals detained while crossing the southern U.S. border over the entire preceding decade. In 2024, the numbers were still significant.

Living in a country that appears so prosperous and flourishing, why are some Chinese people willing to risk their lives and rush toward a foreign country and an unknowable future? In 2022, when I was living in New York and first learned the stories of these Chinese “line-walkers,” this question took root in my heart.

1

Driven by the professional instincts as a former journalist, I began interviewing 19 line-walkers in September 2023. Two years later, I published the book Walking the Migrant Trail: The Path of Life and Death for 15 Chinese People Coming to America.

“Walking the line” is a complex cross-cultural and trans-national issue involving human rights, social justice, immigration policy, cultural conflict, U.S.-China relations, and the shared fate of humanity. Previously, mainstream media outlets including Voice of America, Radio Free Asia, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and BBC have reported on this phenomenon. Among them, WHYNOT, a youth-oriented Chinese-language platform under RFA, produced an in-depth documentary titled Walk the Line, which recorded the arduous journey of these Chinese migrants.

As a former journalist accustomed to the written word, I attempted to use long interviews as a “telephoto lens” to focus on the shifting fortunes and struggles of 15 Chinese line-walkers in both China and the United States. My goal was to present the deeper implications of diaspora, cultural conflict, and identity suspension as they relate to political science, sociology, and anthropology. During the interview process, I strove to trace the primary thread of their fates—what exactly pushed them to make such a desperate choice? I was also searching for the specific turning point in their lives—the final straw that ultimately led to the decision to migrate. In the end, I summarized their motives for leaving into three words: food, freedom, and follow.

In my view, “food” serves as a broad metaphor for economic life. The three years of China’s strict “Zero-COVID” policy caused the economy to plummet, leading to the bankruptcy of small business owners, the collapse of the real estate market, the decline of all industries, and the desolation of the people’s livelihoods. This immense economic pressure was the primary reason for most interviewees’ decision to walk the line and leave China.

For example, I interviewed Liu Cheng, a young man who operated an excavator in Guangzhou. He had taken out loans to buy two houses, turning himself into what Chinese people call a “house slave” (a term for those burdened by massive mortgages). After the pandemic, the Chinese real estate industry collapsed and his income dropped sharply, leaving him unable to maintain his life. Out of necessity, he and his wife walked the line to the United States. “If I were still back home, I would have committed suicide long ago,” he told me.

Among those I interviewed, only a small number walked the line to the United States for the sake of “freedom.” Over the past decade or so, China has tightened its ideological control, the space for free speech has steadily shrunk, and civil society has nearly vanished; many human rights activists, dissidents, and religious figures have been suppressed. For many, this period of time is unbearable. Some of them walked the line to the United States in pursuit of democracy and liberty.

Two young people I interviewed fit this description. One, a man born in the 1990s named Steven Lau, worked in the logistics industry before coming to the U.S., earning a high monthly income of 20,000 to 40,000 yuan. By chance, he used a VPN to bypass China’s Great Firewall and discovered historical events long obscured within the country, such as the Land Reform, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, the Cultural Revolution, and the June 4th massacre of 1989. He wanted to share these truths with his family and friends but discovered that doing so was a political taboo. To pursue historical truth, he walked the line to the United States.

There are also those who believe that walking the line is a social trend or a cool thing to do, so they “follow” others; most of these individuals possess a go-with-the-flow mentality. However, because they lacked sufficient mental preparation and could not endure the hardships of life in the United States, most of them eventually returned to China.

2

In my interviewing and writing, I hoped to move away from traditional, success-oriented immigrant narratives to truthfully present the actual living conditions of these 15 interviewees in the United States. Their lives and their versions of the American Dream are all different—some regret missing the best opportunity to go abroad in their younger years; some survived car accidents during the journey yet insisted on moving forward; some adapted quickly to American life, believing that “America is not heaven, but it is the closest thing to it”; others regret coming to America because “making a living here is not as easy as I imagined” and “if I could choose again, I wouldn’t take this path”; and some chose to return to China quietly.

When these line-walkers risked their lives to enter the United States, they often had no idea what they would face next. They were about to encounter not just the glamorous side of America—its status as the world’s leading power, the strong purchasing power of the U.S. dollar, relatively safe food and medicine, and an education system that respects a child’s individuality—but also its dark side, which includes a rigid immigration system, unsympathetic politicians, political polarization, anti-intellectual mobs, and expensive healthcare. Particularly after Trump’s return to office, policies have become increasingly hostile toward immigrants, pushing their struggle for survival to the extreme. Some interviewees in this book have already cycled through several jobs to evade arrest by ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), living in constant fear.

What I want to convey to readers is a fundamental reality: for many, arriving in the United States is not the end goal of happiness; on the contrary, it may be the start of a difficult life where identity crises, legal risks, financial hardships, and spiritual loneliness persist. This serves as a practical warning to potential immigrants and prevents the romanticization of such a dangerous path.

While writing this book, I strove to bring the grand narrative of immigration back down to the scale of the individual. For a long time, line-walkers have fallen into the cracks between two cultures, their faces remaining blurred. In American public discourse, they are often simplified into numbers, policy issues, or objects of moral debate. Some American politicians frequently use undocumented immigrants as pawns to seize power or attack opponents. Few people view them as living human beings or study them from a human perspective.

Although the paths that the line-walkers and I took to the United States are different, we share a common identity as outsiders, which allows me to empathize with them to a certain degree. Therefore, in writing this book, I did not want to pre-establish any particular stance; I only wanted to restore the interviewees as emotional, sentient individuals and return to them their identities as husbands, fathers, and sons, or wives, mothers, and daughters. My goal was to bring these blurred faces into focus and let the silent stories be heard. In this way, readers can move beyond the binary thinking of right vs. wrong or legal vs. illegal and turn toward a deeper reflection on the human condition—what did these people experience, and why did they make such a choice?

3

Why did I choose the purely objective narrative style of oral history? Because I do not want to provide my own value judgment; instead, I want to leave that judgment to the reader. Between survival, safety, dignity, and rules, how does a person choose, and how far can they go? This book offers not a conclusion, but a collection of empirical facts that are impossible to ignore. These facts remind researchers that any discussion regarding immigration governance, risk control, or institutional design will lose its real-world explanatory power if it cannot address these specific lives existing at the margins of the system.

As Jason De León, a professor of anthropology at UCLA, wrote in the preface to his book The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail: “You have to hear their voices and see their faces to appreciate them as human beings… Perhaps by humanizing that nebulous mass of humanity that we call the undocumented, we can begin to have a serious conversation about how to fix America’s broken immigration system.”

Recently, ICE has been arresting undocumented immigrants indiscriminately, and two incidents of ICE agents shooting and killing American citizens occurred in Minnesota, sparking intense public protests. This has once again triggered a deep reflection on the U.S. immigration system: how can we establish an effective social dialogue to adjust and improve immigration policies? How do we balance the conflict between the legitimate rights of undocumented immigrants and national security, ensuring that these groups do not become victims of political conflict?

In my writing, I shifted the focus of my interviews to the moment they left China—that is, “why did they feel they absolutely had to leave?” These Chinese migrants left their home country, crossed dangerous parts of South and Central America, and faced the constant threat of violence, disease, and death to reach a country whose language, culture, and social systems are entirely different from their own. The motivation behind this courage to seek life by plunging into death reflects the profound changes in contemporary Chinese society and highlights the other side of the so-called prosperous China.

This is a structural problem, not just a matter of personal fate. The reason these 15 people chose to walk the line was not merely due to economic hardship or personal impulse; nearly all of them mentioned one common reason: “I saw no hope in China.” Behind this lie institutional issues, social immobility, family responsibilities, intergenerational anxiety, and the inherent cruelty of the global immigration system. I want readers to understand that walking the line is not the extreme behavior of a few individuals, but rather the result of pressure from multiple social structures; it is a true reflection of the widening wealth gap and the increasingly stratified nature of Chinese society.

In my view, every line-walker is like a puzzle piece. Through these pieces, we can roughly assemble a true image of China today and observe the actual living conditions of the Chinese people—are they the citizens of a strong and wealthy nation, or merely the afterthoughts of a flourishing age?

One could say that this book is more of a cross-section of contemporary Chinese society than just a collection of American immigrant stories. As the author, I hope this book—which possesses none of the traits of a bestseller—will hold archival value in the future. If people look back at this period, they will find clues to the pressures, fractures, and individual choices of Chinese society within these personal stories.

Recommended archives:

Lin Shiyu: Walking the Migrant Trail: The Path of Life and Death for 15 Chinese People Coming to America

WHYNOT documentary: Walk the Line

Thanks, adventurous work you did and good that someone cared.

Curious, did you survey Michal Yon's work on the immigration stream into the U.S. through Mexico, and he covered the Chinese as well?