《软埋》:以文学切入土改历史的禁区

The CCP’s Original Sin: Why a Historical Novel About Land Reform Resonates Today

By Ian Johnson

作者:张彦

The English original follows below.

本文原文为英文。

如果在当下回望,1949年中共建政初期的那一段历史似乎已变得遥远。与今天中国面临的问题相比——最高领导人任期制的取消、对公民社会的打压、日益收紧的思想控制、以及对新冠疫情起源这样重大事件的避而不谈相比,发生在上世纪中叶的事情也许令人遗憾,但似乎已有点无关紧要。

但事实是,发生在当时的土地改革运动至今还发挥着深远的影响。这是一场充斥着暴力、残忍、以及私刑与暴民统治的运动,二十世纪40年代末和50年代初,中共利用这场运动,将中国社会的大部分地区掌控在自己手中。

土地改革对中共如此重要,使得其至今仍是一个终极禁忌,也是这个政权不能被讨论的“原罪”。几十年来,甚至像文化大革命这样的社会大动荡,也在某种程度上可以被批评,但作为共产党夺取政权的基础,土地改革一直是批评的禁区。在官方的叙述中,它被描绘成一场将土地分给贫困农民,使得“耕者有其田”,并为他们带来幸福生活的运动。

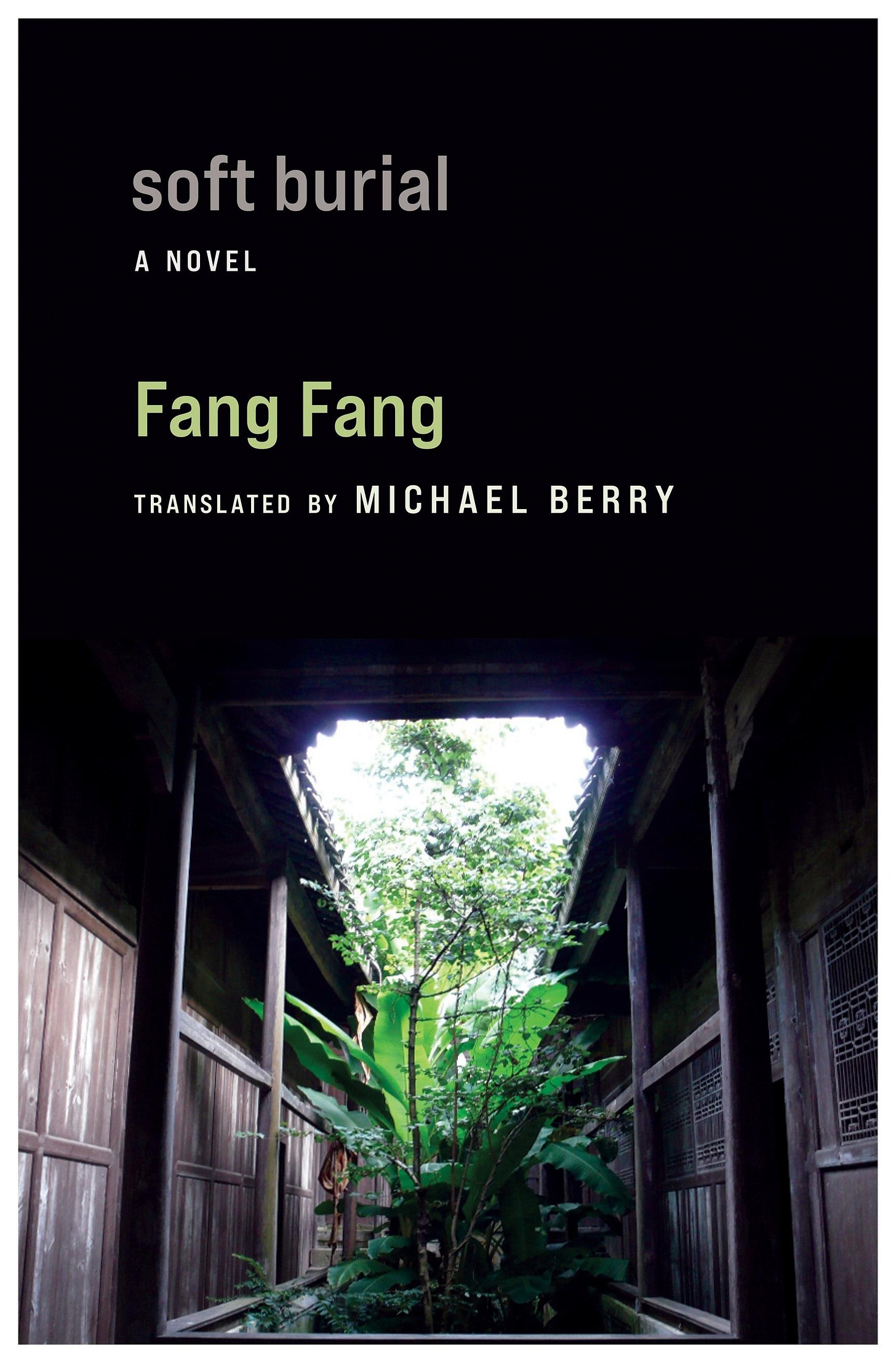

正是在这样的背景下,方方出版于2016年的小说《软埋》就显得尤为重要。事实上,在人民文学出版社首次出版这部小说之前,中国那些独立的历史研究者们,已研究了土地改革多年。但70岁的方方,作为中国最著名的作家之一,作品的影响力显然更大。《软埋》出版后,获得了2017年的路遥文学奖(以作家路遥命名),并引起了广泛讨论,直到遭遇中国极左人士的反击,并最终被官方查禁。

《软埋》一书的标题源于一种“不用棺材来安葬死者”的民间现象。根据中国传统,只有因为灾难发生,匆忙中来不及厚葬死者,才会出现这种特殊的状况。而当时正是土地改革作为“革命”手段横扫中国的时候,中国农村正在遭遇天翻地覆的变化。

在共产党的历史上,旨在让“耕者有其田”的政策曾得到广泛支持,也在所谓“解放区”很大程度上以温和的方式推进。当时的中国,约80%以上的人生活在农村,许多人没有土地,大量土地掌握在少数人手中,农民普遍贫困。这项政策早期在共产党控制的地方实行的时候,地主被允许自愿将土地转让给佃农。一些情况下,边区政府也发行债券,从地主手中和平购买土地,再重新分配给无地农民。

在中共的话语体系中,中国农村被称为“封建社会”,农民被称为“农奴”,使人联想到农奴的悲惨处境,但现实大相径庭。在《软埋》故事发生的四川东部,地主其实平均只拥有2.4亩土地,大多数人与雇工一起下地干活。共产党所称的“地主”往往也是普通农民,只是比邻居多一点地,稍微富裕一些,并不是中共宣传中那种贪婪的魔鬼。

在土地改革这一领域,转折点出现在1947年,当时中国内战的形势正转向有利于共产党的一方。这使得它得以抛弃温和的土地改革政策,指示地方党政干部推动农村暴力革命。(见尾注1。)党政干部们煽动村民“诉苦”,激起对地主的愤怒和仇恨。1949年夺取政权后,共产党加大了压力,将这场运动与针对所谓“反革命分子”的运动结合在一起。

这导致了中华人民共和国第一次大规模的暴力运动。据独立的中国历史研究者估计,多达200万地主被杀害,有的人是全家被杀。(见尾注2。)幸存者则遭到殴打、折磨、被强奸等厄运,并在接下来的30年里都成为政治贱民——被剥夺了工作、晋升或上大学的机会。此后每一次运动,包括1966-76年的“文化大革命”,这些人都是“斗争对象”——这给数千万人带来了难以言状的痛苦。

1950年代,随着党的权力没有了制衡,中国农村陷入了更大的危机。在给予农民土地后不久,共产党又将土地收归国有,建立了人民公社,并实施了导致大饥荒的系列政策,据一些学者的研究,1959年开始的大饥荒造成多达4500万人死亡。(见尾注3。)

即使在今天,中国农民也只拥有土地使用权,而不拥有土地,这剥夺了他们拥有资产的权利,对如何使用土地,他们只能听从党的要求。在后来长达20年的城市化运动中,那些被征地的农民,又不得不放弃土地,只为获得在城市的一套房子,以及微薄的社保金。换句话说,今天中国农村长期存在的问题,大部分根源于当时的土改运动。

这个政治背景构成了《软埋》的基础。小说以当下为背景,讲述了武汉一位寡居的老妇人的故事。她在年轻的时候,大约1950年左右,被人发现昏迷在河岸上,差一点溺水身亡。当她醒来时,患上了失忆症。她受过一定教育——能识别经典小说和神话故事的情节,但救了她的和蔼医生建议她假装失忆。医生告诉她,假装文盲和无知才是她最好的保护。

几年后,这位医生丧偶,他们两人结婚,并生了一个儿子。丈夫去世后,她不得不独自抚养孩子。中国改革开放后,儿子去南方工作,发了财,然后回到武汉。他买了一栋豪华别墅,让母亲搬进去,并计划把妻子和孩子也接过来。

然而,这个本应是幸福的结局,却触动了这位老妇人。财富、繁荣——这一切对她来说反而充满危险,她陷入了昏迷。

小说在两个层面上展开:一个层面是老妇人的内心之旅,她进入了中国神话中的十八层地狱,每一层都揭示着她人生的一个阶段,并从她在河岸被发现的那一刻倒叙。她看到自己抱着一个婴儿在一艘船上,船翻了,孩子淹死了,她被卷入水下。接着她看到自己作为地主儿子的妻子,全家被迫自杀,仆人也随主人死去,而她的父母也被杀死,只因为他们是“地主”。

另一个故事脉络是儿子逐渐开始了解家族的过去。他的父亲给他留下一个箱子,并嘱咐他只有在父母都去世后才能打开。而此时,母亲昏迷不醒,他打开了箱子,在里面发现了日记。日记显示他的父亲也出生在地主家庭,但为了逃避迫害而隐藏了自己的背景。

后来,儿子和一位老朋友一起旅行,这位朋友现在是一名学者,正带领一个学生团队绘制四川东部老宅院的清单。这些老宅曾属于过去的地主与乡绅,但如今已经衰朽。儿子开始拼凑出他家族被压抑的创伤记忆。

作为一部文学作品,这部小说有其缺陷——故事情节几乎完美同步,每一个遗留问题都得到了解决。年轻人不仅巧合地前往了母亲出生的同一个地方,还找到了母亲曾经住过的老宅,以及她逃去河边的秘密隧道。就如书中一个人物惊呼的,“这听起来像一部电视剧!”

尽管如此,这依然是一部引人入胜的小说,方方驾驭多线索故事情节的能力令人印象深刻。当然,这并不奇怪,她本来就是中国最知名的作家之一,她过去就创作了大量以武汉工人家庭为背景的故事。

在中国之外,方方最出名的作品是《武汉日记》。这本书记录了五年前武汉封城的情况,那次封锁最初控制了病毒的传播,但也为中国此后多年日益专断、残酷和无效的“清零”封锁政策埋下了伏笔。

《软埋》一书也挑战了西方许多人对中国的刻板印象。很多人以为中国是一个专制的黑洞,但现实是,尽管压力重重,这个国家仍然拥有广泛的独立作家、思想家和电影人——其中一些人处于社会边缘,但也有一些人,像方方一样,在体制内坚守自己的良知与专业操守。

事实上,《软埋》就是根据谭松教授挖掘的一个真实故事改编的,他多年来一直在研究四川的土地改革。也有其他人从土改时期寻找线索,以解释中国当下正在发生的一切。去年,独立电影制作人王小帅发布了一部关于土地改革的电影《沃土》,这部电影就将当下农村的贫困,直接与当年的土改联系了起来。

但另一方面,在中国,土地改革仍然是一个禁忌话题。2021年,中国国家互联网信息办公室发布了一份需要被禁止的“历史虚无主义”谣言清单,共有十条,其中一条就是“重新审视土地改革”。政府希望人们对过去失忆,但像《软埋》这样的作品表明,尽管困难重重,那些过去的历史,还是正在被人们不断地重新挖掘出来。

尾注:

1. 李放春, 《“地主窝”里的清算风波——兼谈北方土改中的“民主”与“坏干部”问题》,爱思想网,2009年2月4日:https://web.archive.org/web/20221202185703/https://www.aisixiang.com/data/24580.html.

2. 土地改革导致二百万人死亡,参见 Tan Song cited Brian DeMare, Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 161–162.

3. 四千五百万人死亡,参见 Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–1962 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011).

本期推荐档案:

方方:《软埋》

英文翻译版出版社链接:http://cup.columbia.edu/book/soft-burial/9780231214995

The CCP’s Original Sin: Why a Historical Novel About Land Reform Resonates Today

By Ian Johnson

Seen from today’s perspective, the early years of the PRC can seem like ancient history. Compared to problems facing people today—the end of term limits on top leaders, attacks on civil society organizations, ever-tightening ideological control, the refusal to discuss the origins of the COVID pandemic—events from the middle of the last century might be regrettable but irrelevant.

And yet one campaign from that era continues to reverberate today: land reform—a violent, aggressive campaign of torture, murder, and mob rule that the Communist Party used in the late 1940s and early 1950s to bring huge swaths of Chinese society to heel.

Its importance has made it the ultimate taboo, the regime’s original sin that can never be discussed. Over the decades it has been possible to criticize some upheavals, even major ones such as the Cultural Revolution. But land reform is so fundamental to how the party took power that it remains off limits to criticism, portrayed solely as a benevolent campaign that brought fairness and prosperity to China’s long-suffering farmers.

This context is what makes Fang Fang’s 2016 novel, Soft Burial, so important. Independent historians had been exploring land reform for years before Fang Fang’s novel was first published by the People’s Literature Publishing House. But Fang Fang is one of her country’s best-known novelists, a 70-year-old member of the literary establishment. After Soft Burial was published, it won the Lu Yao literary prize (named after the writer Wang Weiguo, who went by the penname Lu Yao) and was widely discussed, until a left-wing backlash prompted censors to ban it.

The novel’s title comes from the practice of burying someone without a coffin, which in traditional China would only be done in haste, usually after a disaster. This is exactly what befell rural China when land reform became a tool for social revolution.

Initially the idea of returning land to the tiller enjoyed broad support and was largely carried out moderately. About 80 percent of Chinese lived in the countryside and many lacked land while some had huge landholdings. Poverty was endemic. Early on, landowners were allowed to voluntarily transfer land to tenant farmers. In other cases, the party issued bonds, used the proceeds to buy out landowners, and then redistributed the land.

The party followed this policy because more radical efforts that had been tried earlier had proven unpopular. In Communist Party jargon, rural China was called “feudal,” and farmers were labeled “peasants,” conjuring up serf-like conditions. The reality was far different. In the eastern part of Sichuan, where Soft Burial takes place, landholders owned on average just 2.4 mu (Chinese acre) of land and most worked the fields alongside hired hands. The people that the party called “landlords” were relatively normal farmers who were only a bit wealthier than their neighbors, rather than the rapacious monsters of Chinese Communist Party propaganda.

Eventually, however, the party dropped moderate policies as it tried to push totalitarian control over the country. The land-owning gentry had been the backbone of traditional Chinese society and a bulwark against radicalism. It was this educated class that built schools, roads, managed temples, and raised militias to fight bandits. If the party was to radically restructure Chinese political, economic, and cultural life, this class had to be destroyed and replaced with a new bureaucratic caste of Communist Party officials.

The turning point came in 1947, when the tide in China’s civil war was turning in the party’s favor. That allowed it to jettison moderation and instruct local party activists to promote violent rural revolution. (See endnote 1.) Party officials urged villagers to “speak bitterness,” whipping up anger and hatred against landowners. After taking power on Oct. 1, 1949, the party ramped up the pressure, twinning the campaign with one against people it called “counter-revolutionaries.”

The result was the first mass campaign of violence in the People’s Republic. Independent Chinese historians estimate that up to 2 million landowners were killed, including entire families. (See endnote 2.) Survivors were beaten, tortured, raped, and became a class of formal outcasts for the next thirty years—denied jobs, promotions, or higher education. Each successive campaign, including the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, further attacked these people, causing unspeakable misery for tens of millions.

With no brakes on the party’s power, rural China plunged into ever-greater crises. Soon after giving the farmers land, the party expropriated it in the mid-1950s to create communes and implement policies that led to the Great Famine, which killed up to 45 million. (See endnote 3.)

Even today, farmers only have land-use rights but do not own their land, depriving them of capital and subjecting them to party directives on how to use the land. During the party’s two-decade-long push to urbanize China many farmers had to surrender even these meager rights in exchange for an apartment and a welfare check. In other words, rural China's persistent problems are partly rooted in the campaigns from that era.

This political story underlies Soft Burial. The novel is based in the present, with the story of an old widower in the central Chinese city of Wuhan whose life seems to be taking a turn for the better. As a very young woman sometime around 1950, she had been found unconscious on the banks of a river, nearly drowned. When she awoke, she was suffering from amnesia. She evidenced some education—she could recognize storylines from a classic novel and mythology—but China was at the beginning of communist rule and so a kindly doctor advised her to hold onto her amnesia. Illiteracy and ignorance, he told her, was her best protection.

After several years the doctor was widowed and the two married. They had a son but the doctor died and the woman had to raise the boy alone. By now the Mao era was over and China was opening up. The son went off to work in China’s southern boomtowns, made good, and returned to Wuhan. He bought an opulent villa and moved his mother in, intending to bring his wife and child.

What should have been a happy end, however, triggers something in the old woman. The wealth, the prosperity—it all seems dangerous to her. She falls into a coma.

The novel continues on two levels: one is the inner journey of the old woman as she travels to the eighteen levels of Chinese hell. Each one reveals a new part of her story, working back chronologically from the time she was discovered on the riverbank. She sees herself on a boat holding a baby, the boat capsizing, the child drowning, and herself being sucked under. Then working back she sees her life as the wife of the son of a landlord, the family’s mass suicide in the face of persecution, the servants dying with them, and her own parents murdered for owning land.

The other storyline is based in the present and concerns her son, who gradually learns about his family’s past. His father has left him a trunk with instructions only to open it when his parents are dead. His mother’s catatonic state leads him to look inside, where he discovers diaries showing how his father had also been born into a landowning family but had hidden his background to escape persecution.

The son later travels with an old friend, now an academic, who is leading a team of students to draw up an inventory of the old villas in the east of Sichuan province. The villas once belonged to the gentry but now are rotting in the mountains. The son begins to piece together his family’s repressed trauma.

As a work of literature, the novel has its flaws. The stories are almost too perfectly synchronized, with every loose end tied up. Not only does the young man coincidentally travel to the same part of the country where his mother was born, but he finds the very villa where his mother once lived, and the secret tunnel to the river that she took to escape. At one point, the story is told to a character in the novel who exclaims “It sounds like a television drama!”

That said, the story is still riveting and Fang’s ability to keep the multiple story lines rolling is impressive. This is little wonder because she is one of China’s best-known writers, who has made Wuhan the site of many of her signature tales about working-class families from the hinterland.

Abroad, she is best-known as the author of Wuhan Diary, an account of the city’s lockdown five years ago, one that initially controlled the virus’s spread but set the stage for years of increasingly arbitrary, cruel, and ineffective lockdowns across China.

Soft Burial challenges some stereotypes that many people have of China. While many say that China is nothing more than an authoritarian black hole, the reality is that the country still has a broad movement of independent writers, thinkers, and filmmakers—some on the fringes of society but some, like Fang Fang, firmly part of the establishment.

Soft Burial, for example, is based on a true story unearthed by Professor Tan Song (谭松), who spent years researching land reform in Sichuan province. Others have also begun to mine this era for clues to China’s current authoritarian malaise. Last year, the independent filmmaker Wang Xiaoshuai released a film on land reform (Above the Dust, or 沃土) that draws a direct line from those events to the impoverishment of rural life today.

Not surprisingly, land reform remains taboo. In 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China issued a list of ten “historically nihilist” rumors that must be banned—one of them, of course, is reconsideration of land reform. The government’s goal is to keep Chinese people in a state of amnesia over the past, but novels like Soft Burial show that the past keeps getting dug up in China.

Endnotes:

1. Li Fangchun 李放春, “Dizhuwo’ li de qingsuan fengbo—jiantan beifang tugaizhong de “minzhu” yu “huai ganbu” wenti, ‘地主窝’里的清算风波——兼谈北方土改中的’民主’与’坏干部’问题,” [The liquidation storm in the “landlord nest”: and talks on “democracy” and “bad comrade” questions in the northern land reform] aisixiang, last modified 4 February 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20221202185703/https://www.aisixiang.com/data/24580.html.

2. 2 million deaths in land reform see Tan Song cited Brian DeMare, Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 161–162.

3. 45 million deaths as per Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–1962 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011).

Recommended archive:

(Publisher URL for the English translation: http://cup.columbia.edu/book/soft-burial/9780231214995)

刚刚读完方方日记,这篇推荐真是太合适了,已经把书加到了清单里,只是不知何时能读完