党文化在中国的定型时刻:延安整风与一套精神控制术的诞生

The Lasting Legacy of Mao’s Yan’an Rectification: The Creation of a Culture of Control

作者:海闻

By Hai Wen

The English translation follows below.

回望中国近百年来的政治历程,不难发现一个基本事实——一种并非源于中国本土,而是从苏联移植过来的党文化,深刻地影响了当代中国的各个方面。

在中国,党文化不仅是一种政治控制的技术,更是一种对全体国人历史记忆与精神世界的深度规训。如果从1949年算起,这种控制与规训至今已延续了70余年。而党文化在中国完成定型的关键一步,就是1942年的延安整风运动。可以说,创作于1948年的著名反乌托邦小说《1984》中的党国雏形,在延安整风中已经铸就,后来的一切,不过是放大而已。

今日的世界,“去苏维埃化”已成为大趋势之一。很多前苏联国家,尤其乌克兰,一直在为去苏维埃化、回归人类主流文明而苦苦奋斗。在对乌克兰寄于深刻同情的同时,中国人其实也应该反观自身——很大程度上,尤其政治文化上,中国仍然主要是一个苏式国家,苏联体制,尤其是布尔什维克党文化的拖累,一直是中国政治社会转型的重大阻力。

中国的布尔什维克党文化,包含但不限于高度集权、领袖崇拜、驯服工具、路线斗争与残酷打击等要素,形成一个环环相扣的内循环系统。从延安整风起,无论是后来五十年代初的全盘苏化,还是当下所谓的“马克思主义中国化”,万变不离其宗,背后都有党文化的身影。中共党内虽偶有自由主义或民主社会主义的涌动,最终都难以撼动布尔什维克式的政治文化底盘。

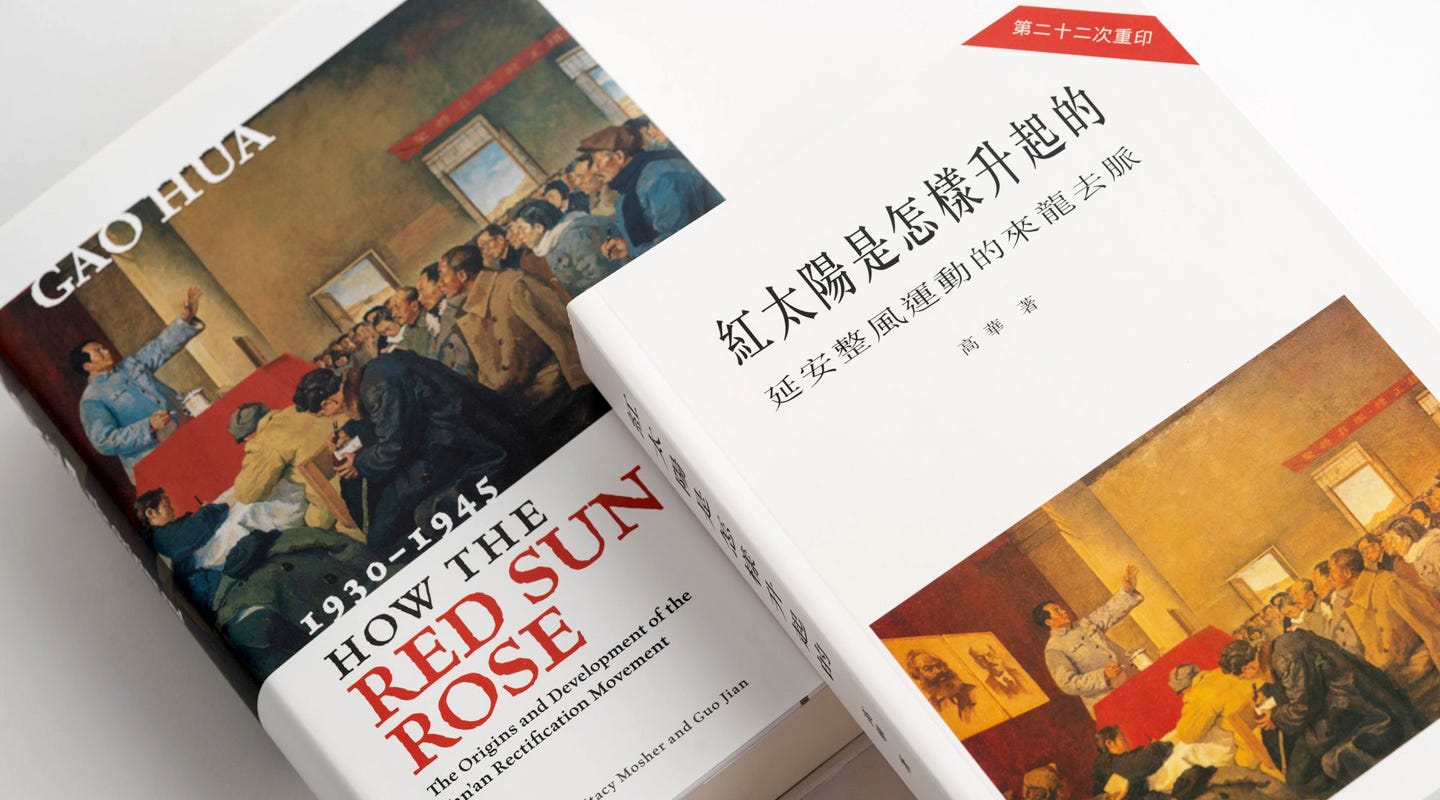

接下来,我们将重点依据何方先生的《党史笔记:从遵义会议到延安整风》(以下简称《党史笔记》),及高华先生的《红太阳是怎样升起的:延安整风运动的来龙去脉》(以下简称《红太阳》)这两部党史名著,深入剖析,开始于上个世纪四十年代的延安整风,如何成为影响中国至今的布尔什维克党文化的铸造工场。

1. 布尔什维克党文化与“一把手拍板”

在中共的主流叙事中,毛泽东于1940年代在延安发起的大规模整风运动,常被表述为一场以“反教条主义”和“反宗派主义”为目标的自我净化运动,其基调往往倾向于描绘某种回归——党组织终于挣脱共产国际外来理论的桎梏,重返“实事求是”的本土精神轨道。

但是,通过《党史笔记》和《红太阳》两部著作提供的证据链,我们可以深入勘察,并看到更逼近历史本质的图景:通过延安整风,中共一方面在人事层面清算了王明等所谓的“莫斯科代理人”,同时又将莫斯科的政治逻辑深植于制度之中,为高度集权的一元化体制,以及党文化的锻造,开启了方便之门。

延安整风实际上是一场权力重组,毛泽东对此心知肚明:谁占用了通往莫斯科的解释通道与联络系统,谁便握有定义“正统”的权柄。《红太阳》揭示,毛泽东应对王明的核心策略,便是切断王明与莫斯科的直接联系,形成“除毛之外,任何人不得染指”的封闭体系。自此,共产国际的权威不再构成对毛的外在约束,而转为其独占性的政治资源。

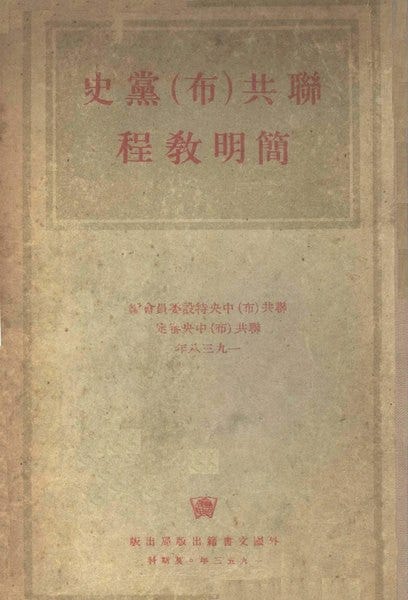

《党史笔记》一书中能看到:延安整风时期,毛在清算王明、博古的第三国际中国路线的同时,也反复公开宣誓对共产国际的忠诚;干部的学习材料里充斥着斯大林与季米特洛夫的圣旨,并以《联共(布)党史简明教程》作为核心读本。王若水曾一针见血:毛批判的只是追随斯大林的王明个人,对斯大林却比王明更忠诚,更加刻意维护斯大林的教主地位,同时宣称要以联共为范例,实现中共自身的“布尔什维克化”。批判锋芒指向“代理人”,但教义“母本”仍被奉为至高圭臬——共产国际的神圣性在体系层面得以完整存续乃至强化。

1942年的延安高干会,更将“布尔什维克化”落实为组织化。《党史笔记》记载,毛在西北局高干会上发表长达两日的长篇报告,题为《斯大林论布尔什维克化十二条》。更早之前,毛已明确提出要建设一个“思想上政治上组织上完全巩固的布尔什维克化的中国共产党”。当“布尔什维克化”被明确为组织建设的目标,整风便从思想讨论转向组织整顿,即转向权力再分配。

延安整风运动的高潮阶段,见证了权力再分配的完成,以及一元化领导即个人集权的落地。《党史笔记》详述,为使毛的领导“更加灵活自如”,1943年5月21日,中央政治局决定成立中央总学习委员会,由毛负总责、康生辅助,自成独立系统,直接统辖各下级分学委。鉴于整风被确立为“压倒一切的中心工作”,并实行“首长负责”制,总学委一度几乎可以号令一切。这已远超单纯的学习管理范畴,而是掌控了组织运行的关键闸门:谁可进入核心圈层,谁被排斥在外;何时暂停日常运转,何时转入正常——这些皆是实现高度集权的关键节点。

《党史笔记》记载,1943年3月20日,政治局会议通过改组书记处的决议,推举毛为政治局及书记处主席,并明文赋予“主席有最后决定之权”。这标志着“一把手拍板”的正式确立。至此,中共的一元化领导体制作为制度成果正式落地。

2. 无声的驯化:党文化的日常生成

如果说经过延安整风,毛成功实现了权力转移,并形成了彻底的个人集权,那么接下来需要追问:这种集权如何渗入日常政治生活的毛细血管?彻底的个人集权不可能仅凭一纸文告便得永固,真正使其成为无声的惯习、内化为个体本能的,乃是一套精巧而持续的精神控制术。

《党史笔记》详细记载了延安整风的一系列制度安排,比如要求党员反复撰写自我反省笔记和思想自传,并通过中央抽阅来挑选典型。这不仅是思想教育,更是一种典型的内殖民:它把个体的内心世界变成了组织可随时检阅的档案,把思想的秘密转化为权力的可控资源。正如高华在《红太阳》中所揭示的,这种做法的最终目的,是在党内塑造一种对领袖个人绝对忠诚、对路线斗争无条件服从的文化氛围。

个人崇拜在此并非简单的偶像化现象,而是通过日常实践进入组织肌理。在延安整风的过程中,对毛个人的神化不再仅仅停留于宣传层面,而是通过一系列“学习—表态—再学习”的循环,把对领袖的崇拜内化为一种组织习惯。正如《党史笔记》所示,整个党组织逐渐从一个多元思潮并存的革命群体,转变为一个对特定权威和官方路线绝对服从的同质化群体。

另外,在行动层面,党开始通过所谓“抢救运动”,展开残酷斗争的哲学,用恐惧实现党员的臣服。《党史笔记》详细描绘了抢救运动如何在延安展开。所谓“抢救失足者”的行动,名义上是为了清除党内的内奸和特务,实际上演变为大规模的逼供和内控。高华在《红太阳》一书中揭示了这一过程的本质:通过不断制造新的敌人来巩固内部的忠诚,通过对嫌疑分子的无端指控来强化对权威的依附。

《党史笔记》记载了大量关于抢救运动中逼供信的细节:许多党员在极端压力下被迫承认自己是特务,并牵连出更多的嫌疑人。这把党内生活推入一种几乎人人自危的状态:人人都可能因无端指控而被推向审查的风口浪尖,人人都必须在公开的批评与自我批评中反复校准自己的语言、态度与记忆。组织通过这种方式不仅清除了所谓异己,更在党员心中深深植入对权力的畏惧,使恐惧成为一种隐形纪律。

可以说,抢救运动不仅是延安整风的一个环节,更是布尔什维克党文化在中国生根发芽的标志性时刻。

3. 党文化的宪章:延安文艺座谈会和《简明教程》

如果说延安整风的组织技术与抢救运动共同塑造了党文化的“权力肌理”,那么《联共(布)党史简明教程》的引入,以及延安文艺座谈会的召开,则为这套党文化打造了更为坚固的宪章。

《红太阳》深刻揭示了《简明教程》在延安时期的影响。这部由斯大林主导编写的党史教程,不仅是对苏联党史的官方诠释,更成为中共重塑自身历史记忆的范本。在整风时期,学习《简明教程》成为全党范围的规定动作,意味着党的历史被重新书写,正确与错误的界限由最高权威加以确立,任何偏离这套历史叙事的声音都被视为异端和潜在的危险。

党文化不再只是政治行动的圭臬,更成为思想与艺术的最高尺度与最大禁忌:它规定什么可以被赞美、被讲述、被传播,也规定什么必须被排斥、被压制、被消失。从世俗领域到宗教领域,党文化如水银泻地,覆盖一切,不留一丝缝隙。

正是在此背景下,延安文艺座谈会成了党文化的又一座里程碑。在座谈会上,毛泽东明确提出文艺必须服务于政治、服务于党的需要,文艺创作不再是独立的精神探索,而是彻底沦为路线斗争和阶级斗争的工具。《党史笔记》对此有生动描述:座谈会不仅确立了文艺的政治从属性,更通过批判所谓的“小资产阶级人道主义”等观念,将文艺领域的多元空间彻底压缩,使得创作者必须在党的意识形态框架内进行自我约束。

在此过程中,《简明教程》和延安文艺座谈会共同构成了党文化的“宪章”:它不仅规范了历史的书写,也规范了文化的想象边界。从此之后,党文化不仅是一种政治实践的规则,更成为思想的牢笼,党文化得以从组织结构扩展到文化结构,从而在更深层次上巩固了其在中国政治文化中的主导地位。

4. 望向将来:党文化何时方能去除?

沿着延安整风的脉络回溯,推敲《党史笔记》与《红太阳》所呈现的种种细节,不能不承认,我们所看到的不仅是一段运动史,更是一种政治文化的生成史:布尔什维克党文化如何在中国的语境中被移植、改造、定型,并最终固化为体制的本能与文化的底色。而要理解当代中国的政治文化,就无法绕过这一源头。

不得不说,直到今天,苏联体制,尤其是布尔什维克党文化的拖累,一直是中国政治社会转型的重大阻力。去苏维埃化、去布尔什维克化,至今仍是中国人不能推卸的时代使命。

在此意义上,今天对党文化,尤其布尔什维克化的反思,既是对历史的追溯,更是对未来的召唤:召唤一种新的政治常识,允许复杂、容忍差异、承认灰度、珍视人的自由与尊严;召唤一种新的公共伦理,不再以持续制造内部敌人来强化同质性,而以正当程序生成制度信任;召唤一种新的文化气质,不再把思想与艺术降格为政治工具,而让它们重新承担人文天职。可以说,唯有去苏维埃化的深层转向真正发生,中国的政治文化才可能获得一次真正意义上的再生。

本期推荐档案:

The Lasting Legacy of Mao’s Yan’an Rectification: The Creation of a Culture of Control

By Hai Wen

Looking back at China’s political trajectory over the past century, one fundamental fact is inescapable: a Party culture—not indigenous to China but transplanted from Soviet Russia—has profoundly shaped every facet of contemporary Chinese life.

In China, Party culture is more than a technique of political control; it is a profound disciplining of the nation’s historical memory and spiritual landscape. Since 1949, this control and indoctrination have persisted for over seventy years. The decisive step in finalizing this Party culture was the Yan’an Rectification Movement of 1942. One could argue that the prototype of the party-state depicted in the famous 1948 dystopian novel 1984 was already forged in Yan’an; everything that followed has merely been an amplification of that original model.

In the world today, de-Sovietization has become a major global trend. Many former Soviet states, most notably Ukraine, have struggled to de-Sovietize. While the Chinese people may feel deep sympathy for Ukraine, to a large extent—particularly regarding political culture—China remains a Soviet-style state. The dead weight of the Soviet system, and specifically the drag of Bolshevik Party culture, remains a primary obstacle to China’s political and social transformation.

China’s Bolshevik Party culture encompasses, but is not limited to, elements such as extreme centralization, a cult of personality, intra-Party struggles, and ruthless purges. Together, these form a self-reinforcing, closed-loop system. From the Yan’an Rectification onward—whether through the total Sovietization of the early 1950s or the current era’s so-called “Sinicization of Marxism”—the essence has remained unchanged. Though ripples of liberalism or democratic socialism have occasionally emerged within the Chinese Communist Party, they have never managed to shake the Bolshevik foundations of the political culture.

Drawing primarily on two seminal works of Party history—He Fang’s Notes on the History of the Chinese Communist Party: From the Zun’yi Conference to the Yan’an Rectification Movement (hereafter Notes) and Gao Hua’s How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan’an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945, (hereafter Red Sun)—we will analyze how the Yan’an Rectification of the 1940s served as the foundry for the Bolshevik Party culture that continues to dominate China today.

1. Bolshevik Party Culture: The Supreme Leader Has the Final Say

In the Chinese Communist Party’s mainstream narrative, the mass Rectification Movement launched by Mao Zedong in the 1940s is often portrayed as a self-purification campaign aimed at what was called “anti-dogmatism” and “anti-sectarianism.” The tone suggests that the Party finally broke free from the shackles of foreign Comintern theory to return to a native path based more on the pragmatic idea of “seeking truth from facts.”

However, the evidence provided by Notes and Red Sun allows us to peer deeper into the historical reality. Through the Yan’an Rectification, the Chinese Communist Party purged people alleged to have been agents of Moscow, such as the Moscow-trained senior party leader Wang Ming, at the personnel level while simultaneously embedding Moscow’s political logic deep within the institutional framework. This paved the way for a highly centralized system and the forging of a permanent Party culture.

The Yan’an Rectification was, in essence, a restructuring of power. Mao understood perfectly that whoever controlled the channels of communication and interpretation with Moscow held the power to define orthodoxy. Red Sun reveals that Mao’s core strategy for dealing with Wang Ming was to sever Wang’s direct link to Moscow, creating a closed system where no one but Mao could access that authority. Consequently, the Comintern’s power ceased to be an external constraint on Mao and instead became his exclusive political capital.

In Notes, we see that while Mao was liquidating the Comintern’s Chinese line (represented by Wang Ming and Bo Gu), he simultaneously and repeatedly pledged his public loyalty to the Comintern. Cadre study materials were saturated with the decrees of Stalin and Dimitrov, with The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course serving as the core text. As Wang Ruoshui incisively noted: Mao did not criticize Stalin; he only criticized Wang Ming for following him. Mao was actually more loyal to Stalin than Wang Ming was, more deliberate in upholding Stalin’s status as a secular pope, and more committed to using the Soviet Party as the blueprint for the Chinese Communist Party’s own Bolshevization.

The 1942 Yan’an High-Ranking Cadres’ Conference translated “Bolshevization” into organizational reality. Notes records that Mao delivered a two-day report titled Stalin on the Twelve Conditions for Bolshevization. Even earlier, Mao had explicitly called for a “Bolshevized Chinese Communist Party that is completely consolidated ideologically, politically, and organizationally.” Once Bolshevization became the organizational goal, rectification shifted from intellectual debate to organizational overhaul—which is to say, the redistribution of power.

The climax of the Rectification Movement saw the completion of this power shift and the institutionalization of one-man leadership. Notes explains that to allow Mao’s leadership to be “more flexible and unconstrained,” the Politburo established the Central General Study Committee in May 1943. Led by Mao and assisted by Kang Sheng, this committee operated as an independent system with direct authority over all subordinate committees. Since rectification was deemed the “overriding central task,” the General Study Committee effectively held sway over everything. This went far beyond mere education; it controlled the vital gates of the organization—determining who entered the inner circle, who was purged, and when normal operations would cease or resume.

According to Notes, on March 20, 1943, the Politburo passed a resolution to reorganize the Secretariat, electing Mao as Chairman of both the Politburo and the Secretariat. Critically, the resolution explicitly stated that “the Chairman has the power of final decision.” This established that the supreme leader has the final say and signaled the official implementation of the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership system.

2. Silent Domestication: The Daily Evolution of Party Culture

If the Yan’an Rectification allowed Mao to centralize power, the next question is: how did this centralization seep into the very capillaries of daily political life? Absolute personal rule cannot be sustained by decrees alone; what truly transformed it into a silent habit—an internalized instinct—was a sophisticated and continuous technique of spiritual control.

Notes details a series of institutional mechanisms used during the Rectification, such as requiring members to write repetitive “self-reflection notes” and ideological autobiographies, which were then sampled by the leadership. This was more than education; it was a form of “internal colonization.” It transformed the individual’s inner world into a searchable archive for the organization, turning private thoughts into a resource for power. As Gao Hua illustrates in Red Sun, the ultimate goal was to foster a culture of absolute loyalty to the leader and unconditional submission to the Party line.

Personality cults were not merely a matter of propaganda; they were woven into the organizational fabric. Through a constant cycle of “study—taking a stand—restudy,” the worship of the leader was internalized as an organizational reflex. As Notes demonstrates, the Party evolved from a revolutionary group containing diverse ideas into a homogenized entity defined by absolute obedience to a single authority.

Furthermore, the Party began utilizing the “Rescue Movement” to implement a philosophy of ruthless struggle, using fear to ensure submission. Notes describes how this movement to “rescue those who have gone astray”—nominally intended to purge spies—devolved into mass forced confessions and psychological terror. Gao Hua reveals the essence of this process: internal loyalty is cemented by the constant manufacture of internal enemies, and dependence on authority is reinforced by the threat of baseless accusation.

Notes records numerous instances of forced confessions during the Rescue Movement, where members under extreme pressure admitted to being spies and implicated others. This created a climate of universal suspicion, where anyone could be targeted and everyone had to constantly recalibrate their speech and memory during public criticism and self-criticism. Through this, the organization did more than purge dissidents; it planted a visceral fear of power in the hearts of its members, making fear an invisible form of discipline.

The Rescue Movement was not just a phase of the Rectification; it was the moment Bolshevik Party culture truly took root in China.

3. The Charter of Party Culture: The Yan’an Forum and the Short Course

If organizational techniques and the Rescue Movement shaped the “power structure” of Party culture, then the introduction of the Short Course on Soviet Party history and the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art provided its “legal charter.”

Red Sun highlights the profound influence of the Short Course. This text, overseen by Stalin, was not just an official history of the Soviet Party; it became the template for the Chinese Communist Party to rewrite its own history. During the Rectification, studying this book became mandatory, ensuring that the Party’s past was reconstructed such that the boundaries of right and wrong were set by the supreme leader. Any deviation was labeled heresy.

Party culture became the ultimate measure—and the ultimate taboo—for thought and art. It dictated what could be praised and what must be suppressed. Like mercury spreading across a floor, it filled every gap of the human experience, from the secular to the spiritual.

In this context, the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art became another milestone. Mao explicitly stated that art must serve politics and the Party’s needs. Creative work was no longer an independent spiritual pursuit but a tool for struggle. Notes describes how the forum not only established the subordination of art to politics but also, by attacking “petty-bourgeois humanitarianism,” crushed the space for intellectual diversity, forcing creators to operate strictly within the Party’s ideological confines.

Together, the Short Course and the Yan’an Forum formed the “charter” of Party culture, regulating not only how history was written but the very limits of the cultural imagination.

4. Looking Forward: When Will Party Culture Be Eradicated?

Tracing the lineage of the Yan’an Rectification through Notes and Red Sun reveals more than just a history of a political movement; it reveals the birth of a political culture. We see how Bolshevik Party culture was transplanted, adapted, and eventually hardened into the instinct of the state. To understand contemporary China, one must understand this origin.

It must be acknowledged that, even today, the drag of the Soviet system—and specifically Bolshevik Party culture—is the primary obstacle to China’s social and political transformation. de-Sovietization and de-Bolshevization remain the unavoidable missions of our era.

In this sense, reflecting on the “Bolshevization” of China is not just about revisiting history; it is a call for the future. It is a call for a new political common sense that accepts complexity, tolerates difference, and treasures human dignity. It is a call for a new public ethics that builds trust through due process rather than the manufacture of enemies. And it is a call for a new cultural spirit that frees thought and art from their role as political tools. Only when this deep de-Sovietization occurs can China’s political culture achieve a true rebirth.

Recommended archives:

Gao Hua: How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan’an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945

He Fang: Notes on the History of the Chinese Communist Party: From the Zun’yi Conference to the Yan’an Rectification Movement (Revised Edition)

“布尔什维克党文化如何在中国的语境中被移植、改造、定型,并最终固化为体制的本能与文化的底色。”我对文章将整风运动理解为主要是苏联影响而非中国本土产物这一点有异议。高华在《红太阳》里多次提到毛对斯的阳奉阴违,对留苏派在权力和思想上的猛烈攻击,以及毛用“马克思主义的中国化”来取代苏联模式。毛的整风运动对中共的影响不是苏联式的,而是中国式的,包括论功行赏、排座次坐江山、帮派文化对内奸的警惕、将宋儒“向内里用力”转为党内清洗、反苏联教条和反智主义,这些都不来自斯大林,不来自“布尔什维克党文化”,而是来自草根中国。否则不能理解鼎革以后中国有名无实的五年计划(毛时代不是计划经济而是领袖指令经济),实为反苏修反教条。