《孤岛》和《一切都会有的》:在独立纪录片中看见中国的自闭症人群

Lonely Island and We Will Have Everything: Seeing China’s Autistic Community in Independent Documentaries

作者:包勉

By Bao Mian

The English translation follows below.

2022年,中国残联为自闭症“正名”,在《关于宣传报道中残疾人及残疾人工作有关称谓的通知》中,公布了10条关于残疾人及残疾人工作的规范称谓。其中第七条指出,自闭症的统一标准称呼为“孤独症”。

“孤独”在中文的语境里比“自闭”的指涉宽泛,“孤独症”因其语义所含的普遍性更容易唤起人们的情感,但也因此消除了自闭症群体在当代社会所处的特殊情境,及支持和理解他们所需要的额外努力。“自闭”本来是从英文单词“autism”翻译而来——词源希腊语“autós”,即指向自我——因此更为贴切。

在中国社会,自闭症群体和其他神经多元人群(包括智力障碍、脑瘫、唐氏综合征等疾病)往往被当作一种与“正常人”不一样的物种,社会人与他们保持跟“不同物种”一样的距离,避免交集和互动。我们在中国的中小学里看不到他们——中国对融合教育这一概念的接受和引进还在起步阶段,而成年人更没有可能在工作空间遇到他们。

这种隐身,也体现在数据中。据中国卫健委2022年统计,中国0至6岁“儿童孤独症”患病率约为0.7%。不过,因诊断体系、认知普及程度和地区医疗资源差异,实际患病率可能远高于0.7%。在韩国和日本,自闭症的确诊率要比中国要高出好几倍。

当神经多元人士出现在公共话语里时,则往往和经过情绪化渲染的悲剧连接在一起,例如:“2018年12月,广西一名自闭症男孩第五次从家里跑出去,被发现时已经溺亡在荒地的沟渠内。”“2018年8月,安徽一位父亲杀害自己12岁的脑瘫女儿,原因是‘实在承受不住了’”——这样极端的叙事切断了公众对神经多元人群的理解——人们只是在新闻里“听说”他们,不需要看到、理解,更不用说与之相处、共存,结果就是难以将他们当作跟自己一样的人来对待。

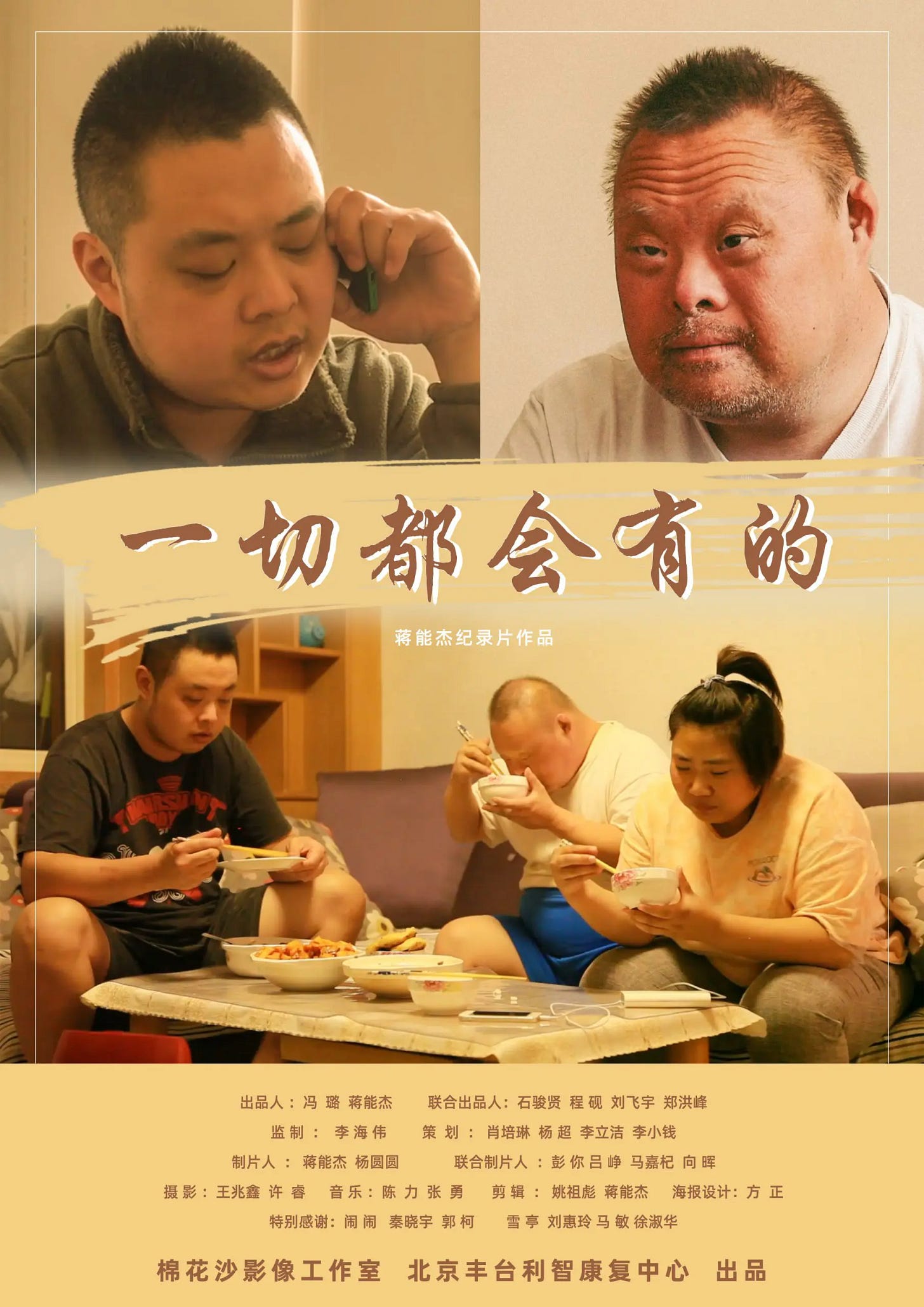

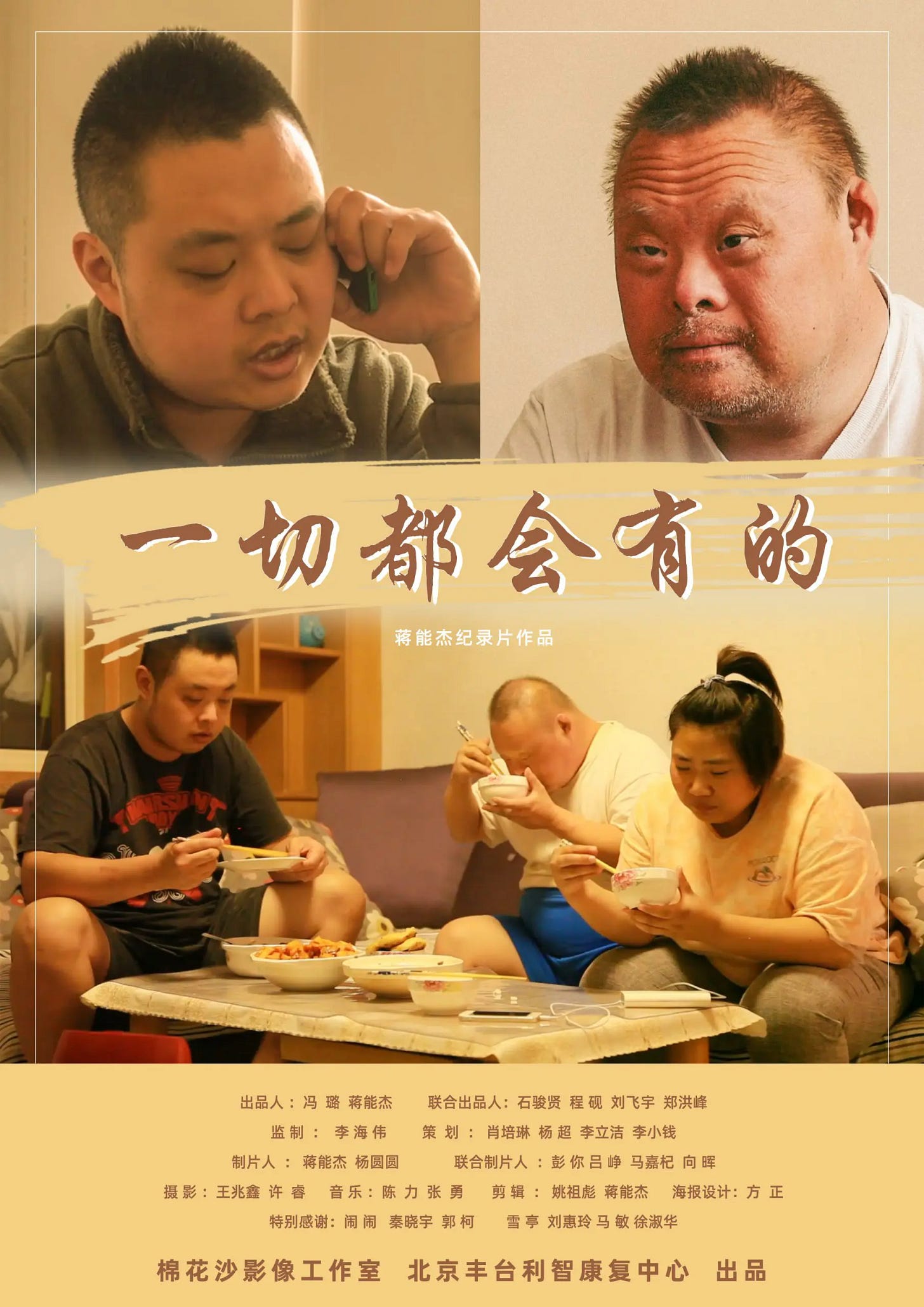

帮助我们看到他们的,是两部关注中国自闭症群体的独立纪录片——海伟的《孤岛》(2014)和蒋能杰的《一切都会有的》(2020)。

海伟的纪录片《孤岛》是中国大陆首部自闭症题材的纪录片。本片制作历时五年,导演海伟跟拍记录了上海四个自闭症少年和家人的生活——除了故事的主体之外,影片也嵌入了参与到这个现实的其他社会行动者,包括自闭症教育机构、公益组织和医院。在中国的公共表达空间里,《孤岛》第一次呈现了处在自闭症谱系不同位置人群的生存现状——具有基本言语能力和日常生活能力,在母亲的陪伴和督促下学习乐器的少年周舒亦;即将从特殊教育专业院校毕业进入社会,在社工的帮助下找工作的施超毅;从同一机构毕业刚开始在社区图书馆工作的肖竞晡;以及有自残倾向,语言和自理能力在四人中最低,并由单亲母亲抚养的菲菲。

人们更容易相信,以及市面上更流行的是关于神经多元人群的天才儿童叙事,比如被叫做音乐神童的舟舟。人们宁愿相信“上帝在给你关了一扇门的时候,一定给你开了一扇窗”,但自闭症群体的现实并不是这样,很多个体的心智可能永远停留在少儿时期。时间带来的改变,并不常见——就如《孤岛》中菲菲妈妈在经历很多次崩溃后,对导演说:“海伟,你知道最难的是什么吗?是你知道明天醒来不会有任何改变。”影片开头呈现出的自闭症群体及其家庭面临的困境,比如菲菲的自残,经过了治疗和挣扎,在结尾并没有得到解决——自闭症群体和家人所处的,是一个将来被悬置的现实。

作为中国大陆第一部目光聚焦于自闭症人群的纪录片,《孤岛》获得了2014年度凤凰纪录片大奖“人文关怀奖”。导演海伟曾为新华社记者,从2010年开始创作独立纪录片,对自闭症群体的跟踪拍摄已经超过十年,至今已制作完成三部自闭症题材的纪录片——《孤岛》、《末路同行》和《简单的心》。

但海伟的作品并不广为人知——这跟拍摄题材有关——关于苦难和黑暗的叙事、及对于社会边缘群体的关注,在中国这样的信息管控背景下,难有广泛传播的空间。这也跟独立纪录片在中国的传播境况,以及民间公益组织在当代中国的存在方式息息相关——而这些因素常常是互相交叉的。

《孤岛》完成后从未在中国正式公映过,也未在流媒体平台(如优酷、爱奇艺)上线,即便是在独立纪录片主要的传播平台(比如纪录片爱好者社区豆瓣和Bilibili私人账号),也只是短暂出现过片源或片段,现实的放映渠道有限。因此,该片多通过学术或公益渠道传播,比如独立纪录片节、学术研讨会(高校自闭症主题讲座)和公益机构(关注自闭症的公益组织和家长互助组织的小型放映会)。《孤岛》最近一次的公开放映大概是在2024年7月,由上海独立文化策展机构——书本映像文化艺术工作室和上海闵行区吴泾慧灵社区助残服务中心合作举办。

这次放映中,主持人这样表述独立纪录片的社会性参与:“无论如何,我们身上的黑暗都会一直存在,用影像记录那些在黑暗更深处挣扎的同胞的生存状况,就是可以被称之为‘公益’的道德责任。”独立纪录片的眼睛常常看到的是光明旁边的黑暗,主流周围的“噪音”(香港录像艺术团体“录影力量”始创成员郑智雄语)——这是它的社会伦理性所在:对不和谐的、看不到出路、处于弱势、失语的、黑暗的表述,以及对人所处的不同现实的呈现——提供使得人理解人的渠道。

这种理解有别于共鸣,它有时候不仅是温暖的、强烈的情感上的共振,而且也是一种需要学习的知识,是一种平静的智性上的要求,如韩国作家金爱烂所说,“是像肌肉一样需要一直保持、训练的‘感觉’,是一种学习和训练。”

这样的理解,是从个人的角度促使人思考,如何建立一个可以容纳不同人的环境——对自闭症的理解,最终是对人的理解,关于人应该如何对待另一个人。在一个高度集权化的社会里,这种理解尤为稀缺,因为一个权力集中的系统往往要去除杂音、泯灭个性,用一致的话语统一所有人的社会性,这导致人们常常忘记,怎样把人当作人来对待。

在这样的背景里,另一位纪录片导演蒋能杰通过作品《一切都会有的》,提供了一种理解和共处的示范。这部影片聚焦于成年自闭症人群(片中的“心智障碍者”),且强调了一种社工的视角。纪录片在疫情前开始拍摄,疫情期间制作完成,导演用两年的时间,在北京一家关注、帮助成年自闭症人群的公益机构——北京市丰台区利智自主生活服务中心,追踪拍摄了成年自闭症群体和周遭人群的生活。

纪录片缘起于蒋能杰本人和利智自主生活服务中心负责人冯璐的早期交流和合作——或许正是因为这样的缘起,本片特别突出了社工在成年自闭症群体生活里的参与方式和理念,以及他们所面临的困境——这让本片在除了呈现现实以外,具有了另一层公众教育意义。某种层面上,每个人都可以通过本片里社工传达的方式和理念对待自闭症人群——归根到底,这种理念和方式,阐释了如何尊重他人——片中的社工提供了一种具体的、现实上的示范。

在当下的中国,相关的公共专业机构和服务设施少之又少——自闭症人群在儿童青少年时期的生活,主要或几乎全部由家庭构成,而当父母年老不具备抚养能力或去世后,他们中的很多人就彻底失去了生活的支撑网络——因为他们一直以来的生活都缺乏家庭以外的社会性。

很多家长最担心的是他们去世后孩子怎么生存——当下的中国除了残联补贴外,对这样的人群基本上完全没有任何机构性支持——政府对自闭症的干预规范发行于2022年,其主要承担机构为乡镇卫生院、社区卫生服务中心和妇幼保健站,而非针对自闭症教育或障碍人群的专门机构。规范中也未提到关于成年自闭症人群的任何支持方式。无论是哪个层面——政府、教育、公众意识,中国社会对自闭症人群的了解都处在起步阶段,自闭症人群在官方文件——即制度性的认识里,被归入残疾人群体,这本身就是非常粗糙和并不有益的命名和认识方式。

所有这些——制度性的空缺、支撑资源的贫瘠,以及公众意识的匮乏——都转嫁到了民间社群机构和公益组织身上。公益组织在对少数边缘群体的关注上常常走在社会前沿,引领着公众意识的改变,和政府的机构性支持——这导致很多人对公益组织有救世主一般的认识(这部分也归因于公众所熟悉的“感动中国”式的英雄主义叙事),也让很多人觉得公益是一种普通人无力实践的社会活动。

但独立纪录片从一个非公益组织行动者的角度,展示了所谓公益最基本的面向——使得公众可以看到平时在社会中被边缘化、被隐藏的暗面,并增加理解——正如《一切都会有的》的豆瓣评论所说:“有时候我们觉得自己并没有做什么,但是我们一个表情,一个眼神,甚至在某个特殊时刻的沉默,都可以成为杀人的刀。”

蒋能杰在《一切都会有的》采访里提到,他有一次在拍摄中陪一位心智障碍者及其母亲一起去肯德基。人比较多,母亲在排队。这位心智障碍者特别喜欢喝可乐,等不及了,就拿起身边桌上的可乐喝,接着就和这杯可乐的主人发生了言语冲突,这位母亲发现时,赶紧过来道歉解释。周围有些人避开了,也有些人在围观。最后,这位顾客还是觉得自己被冒犯了,报警处理。导演说:“我在想,这位母亲回家后是怎样的心情,以后再带孩子出门,得承担多大的压力和勇气。”

我们常常对于“不一样”充满了天然的恐惧,也因此,难以把“不一样”的人(不管是哪种层面的)当作所谓普通人来对待。这部纪录片里除了自闭症群体以外的“主角”——利智自主生活中心的社工们,从一个普通人的角度提供了一种具体的理解和共处的方式。片中记录下一个社工因为用棍棒威胁一位自闭症人而被开除。在那之后,服务中心的指导员杨超说:“我们都知道人与人相处最基本的是互相尊重,这适用于所有人。”

片中的“心青年”(利智中心对障碍者的称呼),需要一直学习,学习做饭,学习表达自己。然而,最主要学会的,是“熟悉尊重他人与被人尊重的感觉”(豆瓣评论)——跟所有人一样,需要感觉到被尊重,才能学会尊重。

利智中心的主要负责人冯璐在演讲中说道:“我们对他们做的不是‘赋权’,权力是天生的,不是我们赋予他们的。”片中社工在心青年情绪激动、有暴力倾向时的具体操作和言语方式给普通人提供了一种示范:杨超在一个心青年拿着砖头要砸玻璃的时候,没有着急向前制止他,而是问他要不要一起来算钱,看看他旅行的钱是不是攒够了,以此来提醒他砸坏东西需要赔钱,在他放下砖头后又帮他一起反思他的情绪经历。

蒋能杰在《脆弱世界》播客的采访中说到,公益纪录片导演有时候像调查记者。不同于阅读新闻报道的是,观看纪录片产生的是一种更为个体的经验和连接,是一种无法被缩写成新闻头条的、需要身心感知的叙事。区别于调查报道,公益纪录片同时嵌入了导演的主体性——属于个人的视角和另类的表达。纪录片也直接作用于个体,作用于每个观看影片的人,而非直接诉求于政府——如果有一个人看了这两部影片而有了一点对自闭症的理解,那也许那位因为儿子喝了别桌的可乐被报警的母亲身上的痛苦会稍微减轻一点点。

而这种理解,不只是情感上的一时共鸣,还是认知上的长期训练。《一起都会有的》弹幕评论心青年刘浩“好可爱啊”、“好萌啊”。可作为一个四十多岁的成年人,不处于这些“可爱”瞬间的他在现实世界遇到的可能就是被报警,被强制驯服。

所以说,理解不是要看到自闭症群体的“天真无邪”,而是要懂得当他们不“可爱”的时候,当他们因为情绪无法沟通而暴躁甚至趋向暴力时,如何关爱,如何尊重。

(本文作者曾从事自闭症儿童教育工作。)

本期推荐档案:

《孤岛》(导演:海伟)(片源请见民间档案馆影片介绍中的互联网档案馆链接)

《一切都会有的》(导演:蒋能杰)(片源请见民间档案馆影片介绍中的互联网档案馆链接)

Lonely Island and We Will Have Everything: Seeing China’s Autistic Community in Independent Documentaries

By Bao Mian

In 2022, the China Disabled Persons’ Federation standardized the terminology for autism. In an official document, it released ten standardized terms for use concerning people with disabilities. Specifically, Article 7 of the notice pointed out that the official, standardized term for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is “loneliness disorder” (gūdúzhèng).

Loneliness is a term that more easily evokes public sympathy, even though the more accurate term is zìbì (“self-enclosed”, coming from the Greek root of autism, autós, which means “self”). Although well-meaning, the terminological differences highlight the problems that people with autism have in Chinese society—pitied but also with their problems inadvertently downplayed and turned into merely a kind of loneliness.

The overall effect in Chinese society is that the autistic community and other neurodivergent individuals (including those with intellectual disabilities, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, etc.) are often treated as a distinct species from “normal people.” Consequently, the general public maintains a distance from them, avoiding interactions and engagement. We do not see them in China’s primary and secondary schools—the adoption and introduction of the concept of inclusive education are still in the early stages in China—and it is even less likely for adults to encounter them in the workplace.

This erasure extends to statistics as well. According to 2022 statistics from China’s National Health Commission, the prevalence of “childhood autism” among children aged zero to six in China is approximately 0.7%. However, due to differences in diagnostic systems, public awareness, and regional medical resources, the actual prevalence may be much higher than 0.7%. In other East Asian countries, such as South Korea and Japan, for example, the rate is several times higher.

When they do appear in public discourse, neurodivergent individuals are typically associated with sensationalized headlines. For example: “In December 2018, an autistic boy in Guangxi ran away from home for the fifth time and was found drowned in a ditch.” “In August 2018, a father in Anhui murdered his 12-year-old daughter with cerebral palsy, stating that ‘he simply couldn’t bear it anymore.’” Such extreme narratives prevent the public from truly understanding neurodivergent individuals. People merely hear about them in the news; they feel no need to see them, understand them, much less coexist with them.

Two independent documentaries that help us see this community are Hai Wei’s Lonely Island (2014) and Jiang Nengjie’s We Will Have Everything (2020), both of which focus on the autistic community in China.

Hai Wei’s documentary Lonely Island is the first film in Mainland China to focus on autism. The film took five years to produce, with director Hai Wei tracking the lives of four autistic adolescents and their families in Shanghai. Beyond the main subjects, the film also incorporates other social actors, including autism education institutions, non-profit organizations, and hospitals.

Lonely Island was the first film in China’s public sphere to present the lives of people at various points on the autism spectrum: Zhou Shuyi, an adolescent with basic verbal and living skills who practices a musical instrument with his mother’s accompaniment and supervision; Shi Chaoyi, who is about to graduate from a special education college and enter society, seeking work with the help of social workers; Xiao Jingbu, who recently graduated from the same institution and started working in a community library; and Feifei, who has self-harming tendencies, possesses the lowest verbal and self-care abilities among the four protagonists, and is raised by a single mother.

The narratives people more readily believe, and that are more popular in the market, are those about neurodivergent prodigies, such as Zhou Zhou, a man with cerebral palsy who later became a musical conductor. People prefer to believe that “God must open a window when he closes a door for you,” but the reality for autistic patients is often quite different; many patients’ mental capacity may remain permanently at childhood.

Change brought about by the passage of time is rare—as Feifei’s mother said to the director after one of many breakdowns in Lonely Island: “Hai Wei, do you know what the hardest part is? It’s knowing that nothing will change when you wake up tomorrow.” The difficulties faced by autistic patients and their families, such as Feifei’s self-harm, presented at the beginning of the film, are not resolved at the end, as people with autism and their families exist in a reality where the future is suspended.

As the first documentary in Mainland China to focus on the autistic community, Lonely Island won the “Humanitarian Award” at the 2014 Phoenix Documentary Awards. Director Hai Wei, a former Xinhua News Agency journalist, began creating independent documentaries in 2010. He has followed the autistic community for over a decade, completing three documentaries on the subject: Lonely Island, The End of the Road, and A Simple Heart.

However, Hai Wei’s work is not widely known. This is partly due to the subject matter—narratives concerning suffering and marginalized social groups face significant barriers to widespread dissemination under China’s censorship regime. It mirrors the challenge for distributing independent Chinese documentaries and the difficulty for survival facing non-profit organizations in China.

After its completion, Lonely Island was never officially screened in China, nor was it available on streaming platforms. Even on the main dissemination channels for independent documentaries, such as Douban and Bilibili, source footage or clips appeared only briefly, and real-world screening channels are limited. Consequently, the film is mostly distributed through academic or non-profit channels, such as independent film festivals, academic seminars (university lectures on autism), and small screenings held by non-profit organizations and parent support groups focused on autism. One of the most recent public screenings of Lonely Island was in July 2024, co-organized by a Shanghai independent cultural curation organization and a local disability assistance service center.

During this screening, the host described the social contribution of independent documentaries: “No matter what, the darkness within us will always exist, and using film to record the lives of our compatriots struggling in the deeper darkness is a moral responsibility that serves the public interest.”

The focus of independent documentaries is often the darkness alongside the light, the noise around the mainstream. This is the source of their social ethics: they articulate the discordant, the hopeless, the vulnerable, the voiceless, and the dark, presenting different human realities—thereby providing a channel for people to understand one another.

This type of understanding differs from mere empathy; it is sometimes not only a warm emotional resonance, but also knowledge and intellectual growth. As the Korean writer Kim Ae-ran suggests, it is a “sense that needs to be maintained and trained like a muscle.” This understanding prompts individuals to consider how to create an inclusive environment that can accommodate diverse people—the understanding of autism is ultimately the understanding of humanity, of how one person should treat another. In a highly centralized society, this type of understanding is particularly scarce because a centralized power system tends to eliminate dissent, suppress individuality, and unify everyone’s social behavior through a single narrative, often leading people to forget how to treat a person as a person.

Against this backdrop, another documentary director, Jiang Nengjie, offers a model of understanding and coexistence through his work, We Will Have Everything. This film focuses on adults with autism and emphasizes the perspective of the social worker. Filming began before the COVID-19 pandemic and concluded during it. The director spent two years tracking the lives of adults with autism and those around them at the Lizhi Autonomous Living Service Center, a non-profit organization in Beijing.

The documentary originated from the collaboration between Jiang Nengjie and Feng Lu, the head of the Lizhi Center. Perhaps because of this connection, the film particularly highlights the social workers’ methods and philosophy of participation in the lives of adults with autism, as well as the challenges they face.

This gives the film an additional layer of public educational significance beyond merely presenting reality. At some level, everyone can apply the methods and philosophies conveyed by the social workers in this film when interacting with autistic people, for this approach explains how to respect others, as the social workers in the film provide a concrete, real-world example.

In China, relevant public professional institutions and services are extremely limited. The lives of autistic individuals during childhood and adolescence are primarily, if not entirely, structured by the family. When parents age and can no longer provide care or pass away, many autistic adults lose their entire support network because their lives have always lacked social engagement outside the home.

Many parents’ greatest fear is how their children will survive after they are gone. Outside of subsidies from the Disabled Persons’ Federation, there is virtually no institutional support for the autistic population. Government intervention standards for autism, issued in 2022, primarily assign responsibility to general community medical centers, not specialized institutions for autism education or people with disabilities. Furthermore, the standards do not mention any support methods for autistic adults. On every level—government, education, public awareness—Chinese society’s understanding of the autistic community is in its initial stages. Autistic people are classified as a disabled group in official, institutional recognition, which is itself a rather crude and unhelpful way of defining and viewing them.

All of these factors—the institutional vacuum, the scarcity of resources, and the lack of public awareness—are transferred onto grassroots community organizations and non-profit groups. Non-profit organizations are often at the forefront of caring for marginalized groups, driving changes in public awareness and lobbying for government institutional support. This can lead to people viewing non-profits as saviors and make many feel that non-profit work is something that ordinary people cannot undertake.

However, public interest documentaries demonstrate the most fundamental aspect of public service: enabling the public to see the marginalized and hidden aspects of society, and fostering understanding—as an online comment on We Will Have Everything says: “Sometimes we feel like we haven’t done anything, but one expression, one look, or even our silence at a special moment, can become a murderous knife.”

In an interview about We Will Have Everything, Jiang Nengjie recalled accompanying an intellectually disabled person and their mother to a KFC during filming. The restaurant was crowded, and the mother was queuing. The person, who loved cola, couldn’t wait, picked up a cup of cola from a nearby table, and drank it, leading to a verbal conflict with the cup’s owner. When the mother noticed, she rushed over to apologize and explain. Some bystanders moved away, while others watched. Ultimately, the customer still felt offended and called the police. The director reflected: “I was thinking, how must this mother have felt when she went home, and how much pressure and courage would be required to take her child out again in the future?”

We often have an inherent fear of difference, which makes it difficult to treat people who are different as ordinary people. The social workers at the Lizhi Center offer a specific approach to understanding and coexistence from the perspective of an ordinary person. The film records one social worker being fired for using a stick to threaten an autistic person. Afterward, the center’s instructor, Yang Chao, said: “We all know that the most basic thing in human interaction is mutual respect; this applies to everyone.”

The autistic adults in the film must continuously learn—cooking, managing their emotions, and expressing themselves. However, the most essential thing they learn is to “become familiar with the feeling of respecting others and being respected,” as an online comment summarized. Like everyone else, they need to feel respected to learn how to be respectful.

Feng Lu, the head of the Lizhi Center, stated in a speech: “What we are doing for them is not ‘empowerment’; power and rights are inherent, not something we grant them.” The documentary provides a model for ordinary people through the specific actions and language used by the social workers when a patient is emotionally agitated or violent: when one autistic youth picked up a brick to try to smash a window, Yang Chao did not rush forward to stop him. Instead, he asked him if he wanted to count his money to see if he had saved enough for his trip, reminding him that he would have to pay for any damage. After the youth put the brick down, Yang Chao helped him reflect on his emotional experience.

Jiang Nengjie noted in an interview on the Vulnerable World podcast that public interest documentary directors are sometimes like investigative journalists. Unlike reading news reports, however, watching a documentary creates a more individual experience and connection, a narrative that requires physical and emotional engagement and cannot be condensed into a headline. Distinct from investigative reporting, public interest documentaries also incorporate the director’s subjectivity—a personal perspective and an alternative expression. Documentaries also directly affect the individual audience, rather than directly appealing to the government. If one person watches these two films and gains even a little more understanding of autism, perhaps the suffering of the mother who had the police called because her son drank someone else’s cola will be slightly eased.

And this understanding is not just temporary emotional resonance, but long-term cognitive training. Online bullet screen comments on We Will Have Everything praise one protagonist Liu Hao as “cute” and “adorable.” Yet as a man in his forties, when he is not in these “cute” moments, Liu may encounter being reported to the police and forcibly subdued.

Therefore, understanding is not about seeing the autistic persons’ innocence. It is about when they are not “adorable,” when they are irritable or even prone to violence due to their difficulty in expressing emotions, we still know how to respect them.

(The author of this article has experience working with autistic children.)

Recommended archives:

Lonely Island (Director: Hai Wei) (available on the Internet Archive with Chinese subtitles)

We Will Have Everything (Director: Jiang Nengjie) (available on the Internet Archive with English and Chinese subtitles)