当我们谈论“敏感”时,我们在谈论什么?——从《政治中国》看中国政治

What We Talk About When We Talk About “Sensitivity”: Chinese Politics Through the Lens of Political China

作者:甘玟

By Gan Min

The English translation follows below.

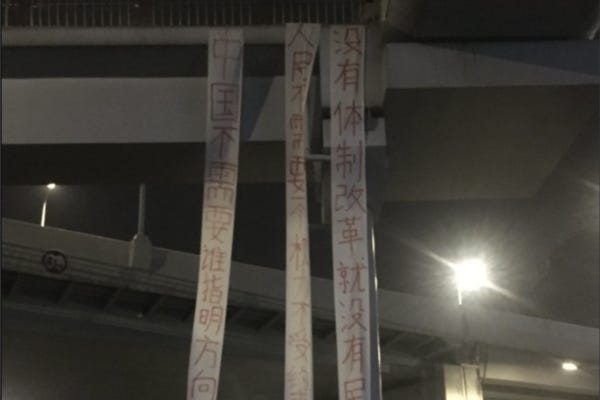

2025年4月15日,四川青年梅世林在成都的一座人行天桥上挂出三条抗议标语。这三条标语写道:“没有体制改革就没有民族复兴”、“人民不需要一个权力不受约束、责任不可追问的政党”、“中国不需要谁指明方向,民主才是方向”。标语在天桥上悬挂三小时,但梅世林随后失联,据报道已被中国官方刑事拘留。

在当下的中国,贴出这种标语,需要远超常人的勇气。但仔细读来,这三句抗议标语的主张和价值观——政治体制改革、制约权力、民主——没有一个违反任何中国的法律,反而都是中国共产党承认、支持的。所以,中国人有必要替梅世林发声,并质问官方:一个中国人说出这三句话,凭什么就要被抓捕?

在梅世林的标语中,“体制改革”——也就是“政治体制改革”,恐怕是中国人曾经很耳熟,如今却很陌生的一个概念。政治体制改革作为八十年代中国共产党的改革目标之一,为什么逐渐沦为“敏感词”,直到今天成为中国政治语境中的禁忌?

在改革开放年代,政治体制改革经常与经济体制改革一并提起,但是多年来,论述政治体制改革的文章和著作则少之又少。出版于1998年的《政治中国:面向新体制选择的时代》,正是一部稀有的、曾正式出版并聚焦于中国政治体制改革的书。因为有关政治体制改革方面的文章少之又少,《政治中国》得以在近400页内收纳了截至九十年代末,几乎所有在中国发表过的对政治体制改革进行论述的文章。

《政治中国》收录的四十篇文章,有两位编者董郁玉和施滨海(笔名“斯人”)的贡献,也来自有着不同背景和观点的作者,其中既有共产党的元老(朱厚泽、李锐),也有体制内的笔杆子(如王沪宁),还有众多著名的学者和媒体人,如江平、龚祥瑞、刘军宁、李曙光、蔡定剑、何清涟、俞可平、秦晖、黄钟。

书中收录的文章,对政治体制改革所包含的宪政、民主、法治、基本权利等“普世价值”有着较为完整、深入的阐述,也为读者呈现出了九十年代末中国知识界对普世价值的认知水平和研究水准。

虽然书中的每篇文章都分别曾在中国公开发表,但是《政治中国》把它们聚集到一起后,却很快成为禁书。就连出版该书的今日中国出版社也因此受到连累,不久后在官方的压力下停止运营。这是因为,在中国,论述政治体制改革的文章,即使能够单独发表在期刊和报纸上,也只是存在于官方语言体系的边缘。一旦聚集,这些文章就好像五个手指攥到了一起,形成了一股足以冲击主流的力量。

政治体制改革在中国虽然曾一度有讨论的空间,但是即使在九十年代,此书编者也深知这个题材的“敏感性”。而与“敏感性”并存的,是政治体制改革对中国人、中国政治和中国未来的重要性。在《政治中国》的序中,被誉为“中国法学界的良心”的江平教授写道:

“政治体制改革的确敏感。但是,所谓‘敏感’能否构成不进行政治体制改革的理由?能否构成缓行政治体制改革的理由?如果政治体制中的诸多弊端能够因其本身的‘敏感’而消弭的话,那么,改革无疑就是多余的了。然而,事情明摆着,政治体制中的实际问题怎么可能会在无所作为中得到解决呢!”

“敏感”的本义,指人体神经对某些外界刺激的反应很快,甚至过激。但中国政治话语中的“敏感”,脱不开“禁忌”的意味,也带着一种贬义的色彩。然而,“敏感”并不等同“不好”,即使是在中国,在《政治中国》出版的那个年代,体制内外,会说政治体制改革“敏感”,但几乎没人会说政治体制改革“不好”。

正因为政治体制改革是个好东西,共产党才会把它确立为改革的目标。八十年代主动提出政治体制改革的背景,是毛时代的种种灾难。在中国的语境下,政治体制改革是共产党主导的积极改良,不是要削弱共产党的领导地位,也绝不是外部力量带来的“颜色革命”。

正如《政治中国》收录的现任中央政治局委员王沪宁于1997年在人民日报发表的文章中所说:“政治体制改革是社会主义制度的自我完善,不是要改变社会主义的根本制度,而是要改革那些不适应社会生产力发展和人民要求的具体制度和体制。”这种防止重蹈毛时代覆辙的自我完善,明明是为了让共产党更稳定、更长久地执政,怎么就成了一个“敏感”的话题?

政治体制改革“敏感”的真正原因,是因为中国民众与现有体制以及该体制下的既得利益者,有着某种难以化解的根本性利益冲突。《政治中国》中收录的编者之一董郁玉的文章,对此有所洞见:

“在政治体制上所做的任何变动,都不可避免地影响到已经从现体制取得相对稳定收益的人的利益。问题的复杂性也正在于此。在中国,政治体制改革是一个自上而下的过程,因此,对政治体制改革的设计,对未来政治制度的安排,对政治体制改革进程的总体把握等,都要由在现体制中取得实际收益的人来作出决定,而这样的决定往往需要他们自己在某些方面和某种程度上首先作出一定的牺牲。”

可见,所谓的“敏感”,其实是中国现行体制下那些既得利益者的过激反应。既得利益者们不仅害怕政治体制改革造成自身利益的损失,也非常担心政治体制改革会撼动一党专制的根基。

而《政治中国》的编者,以及江平教授和书中文章的大多数作者们,都清楚政治体制改革的“敏感”,却选择毫不回避地讨论民主、宪政、法治、权利,展现了中国知识界应有的脊梁。

不过,《政治中国》的编者们恐怕没有想到,他们出书时的最坏设想,竟不幸一语成谶:“作为编者,我们希望此书的出版能够为政治体制改革讨论的空间拓展作些有益的铺垫。如果不是这样,甚或出现相反的结局,那么,这绝非仅仅意味着编者个人的不幸……”

本书的两位编者长期活跃在中国知识界,但都遭遇不幸。施滨海先生于2018年在一场意外中逝世,而董郁玉先生,则由于长期呼吁宪政改革因言获罪,2022年被中国政府在毫无证据的情况下污蔑为间谍,至今身陷囹圄。

为《政治中国》贡献文字的几位作者,包括江平、李锐、朱厚泽、蔡定剑,已经去世,没有能够看到中国实现民主、法治、宪政的那一天。蔡定剑教授英年早逝,他留下的一句名言“宪政民主是我们这一代人的使命”,也不知能否在他同辈们的有生之年成为现实。

中国政局陷入的困境以及中国民众在此困境下遭遇的不幸,至今早已有目共睹。说到底,这种不幸的缘由,正是执政党及其具体的既得利益者们拒绝为改革放弃自身利益。不过,或许能理解的是,在权力的夹持之下,他们的自身利益太过庞大。他们的权力至高无上,高于法律,大过党章,而他们的财富则是天文数字。可以说,这个自称“为人民服务”的权力精英阶层,才是中国真正的“主人”。

如果既得利益者们根本不会选择牺牲自身的利益,那么政治体制改革是否只是理论性的存在?如果政治体制改革在改革开放以来的四十多年都没有在共产党的领导下发生,那么我们有什么理由相信,同样的掌权者们在可预见的未来,能够主动变革?

政治体制改革,说到底是一种自上而下的、保守的、由既得利益者掌控生杀大权的改革。这种改革最大的优势是和平,因为它本质上不是革命,而是改良,不是权力的更替,而是既得利益者对划分蛋糕规则的调整。相比之下,自下而上的变革,则很极有可能会让社会各个阶层的人——包括高高在上的既得利益者们——付出更高昂的代价。

这也是曾经呼吁政治体制改革的自由派学者们当时普遍的认识。如今,随着那个曾经还可以讨论问题的时期结束,在当政者开起历史倒车的当下,普通人每时每刻都在为现有制度的不公付出着代价。也许,当非既得利益的群体越发不能承受改革停滞的代价时,既得利益者也会失去这种“自上而下”改良的机会。而《政治中国》的编者和作者们,恐怕在当时还没有预料到会有失去政治体制改革这个选项的那一天。

无论中国的未来是自上而下的改良,还是自下而上的变革,如果要想实现民主、宪政、法治、自由,建立更好的政治制度,众人的努力是必不可少的。《政治中国》的两位编者在近三十年前写下的后记里,也有给今天的我们的寄语:

“怎么可以想像,仅靠几十个大脑的思考,仅靠几十支笔的写作,仅靠几十张嘴的呼号,就可以成就中国的政治体制改革!退一万步说,如果中国的政治体制改革真的能够在众人漠视的缄默中成功的话,那么,那些身处这一过程却无所事事的人们,是否会觉得有愧于这一成就、有愧于这个时代呢?”

漠视缄默的后果,我们今天已经十分清楚。所以,我们需要更多个大脑的思考,更多支笔的写作,以及更多张嘴的呼号,才有可能促成变革,才能让前辈们对改革的探究与思索没有白费,才能确保梅世林、彭立发等勇者发出的呐喊,能够回响在中国的土地上。

本期档案推荐:

What We Talk About When We Talk About “Sensitivity”: Chinese Politics Through the Lens of Political China

By Gan Min

On April 15, 2025, Mei Shilin, a young man from Sichuan, displayed three protest banners on a pedestrian overpass in Chengdu. These banners read: “No national rejuvenation without political system reform,” “The people do not need a political party with unchecked power and no accountability,” and “China does not need anyone to point the way; democracy is the direction.” The banners were hung for three hours, but Mei Shilin subsequently disappeared and has reportedly been criminally detained by Chinese authorities.

Displaying such banners in contemporary China requires extraordinary courage. Yet, upon closer inspection, the claims and values expressed in these three protest slogans—political system reform, checks on power, and democracy—do not violate any Chinese laws. On the contrary, they are all concepts acknowledged and supported by the Chinese Communist Party. Therefore, it’s imperative for Chinese people to speak out for Mei Shilin and demand an answer from the authorities: what is the legal and moral basis for arresting a Chinese citizen for uttering these three sentences?

Among Mei Shilin’s slogans, “political system reform” is perhaps a concept that was once familiar to Chinese people but is now largely alien. Political system reform was one of the Chinese Communist Party’s reform goals in the 1980s. Why has it gradually become a sensitive word and a taboo in China’s political discourse?

During the era of reform and opening up, political system reform was often mentioned alongside economic system reform. However, over the years, articles and works discussing political system reform have been exceedingly rare. Political China: Towards an Era of Choices for a New System, published in 1998, is one such rare book that was officially published and focuses on China’s political system reform. Because articles on political system reform were so scarce, Political China was able to collect almost all articles on political system reform published in China up to the late 1990s within its nearly 400 pages.

The forty articles included in Political China feature contributions from its two editors, Dong Yuyu and Shi Binhai (pseudonym “Siren”), as well as authors with diverse backgrounds and viewpoints. These include veteran Communist Party members (Zhu Houze, Li Rui), party insiders (such as Wang Huning), and numerous renowned scholars and media professionals, including Jiang Ping, Gong Xiangrui, Liu Junning, Li Shuguang, Cai Dingjian, He Qinglian, Yu Keping, Qin Hui, and Huang Zhong.

The articles in the book provide a relatively comprehensive and in-depth exposition of the universal values encompassed by political system reform, such as constitutionalism, democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental rights. They also demonstrate the level of understanding of the Chinese intellectual community regarding universal values in the late 1990s.

Although each article in the book had been previously published in China, Political China quickly became a banned book for simply compiling these articles. Even the publisher, Today China Publishing House, was implicated in the ban and later ceased operations under official pressure. This is because articles discussing political system reform, even if they could be published individually in journals and newspapers, only existed at the fringes of China’s official discourse. Once gathered, these articles were like five fingers forming a fist, creating a force strong enough to challenge the mainstream.

While political system reform once had room for discussion in China, even in the 1990s, the book’s editors were well aware of the sensitivity of this topic. Coexisting with this sensitivity was the importance of political system reform for the Chinese people, Chinese politics, and China’s future. In the preface to Political China, Professor Jiang Ping, hailed as “the conscience of the Chinese legal community,” wrote:

“Political system reform is indeed sensitive. But can ‘sensitivity’ constitute a reason not to undertake political system reform? Can it constitute a reason to delay political system reform? If the many drawbacks in the political system could disappear because of their ‘sensitivity,’ then reform would undoubtedly be superfluous. However, it is clear that actual problems in the political system cannot possibly be resolved through inaction!”

The original meaning of “sensitive” refers to the quick, even excessive, response of the human nervous system to certain external stimuli. But in China’s political discourse, “sensitive” carries the connotation of “taboo” and a derogatory nuance. However, “sensitive” does not equate to “bad.” Even in China, during the era when this book was published, people within and outside the system would say political system reform was “sensitive,” but almost no one would say political system reform was “bad.”

Precisely because political system reform is a good thing, the Communist Party established it as a goal of reform. The background for proactively proposing political system reform in the 1980s was the various disasters of the Mao era. In the Chinese context, political system reform is a positive improvement led by the Communist Party. It is not meant to weaken the Communist Party’s leadership, and it’s by no means a “color revolution” brought about by external forces.

As Wang Huning, a current member of the Politburo, stated in an article published in the People’s Daily in 1997 and included in Political China: “Political system reform is the self-improvement of the socialist system, not to change the fundamental socialist system, but to reform those specific systems and mechanisms that do not adapt to the development of social productive forces and the demands of the people.” This self-improvement, which aims to prevent a repeat of the Mao era’s mistakes, was clearly intended to ensure the Communist Party’s more stable and long-lasting governance. So how did it become a sensitive topic?

The real reason for the sensitivity of political system reform is the fundamental conflict of interests between the Chinese public and the existing system and its vested interests. An article in Political China by Dong Yuyu, who is one of the editors of the book, offers some insight into this conflict:

“Any change made to the political system will inevitably affect the interests of those who have already gained relatively stable benefits from the current system. The complexity of the problem lies precisely here. In China, political system reform is a top-down process. Therefore, the design of political system reform, the arrangement of future political institutions, and the overall grasp of the political system reform process must all be decided by those who have gained actual benefits from the current system, and such decisions often require them to make certain sacrifices in some aspects and to some extent first.”

It’s clear that the so-called “sensitivity” is actually the overreaction of those vested interests under China’s current system. For the powerful political elites, political system reform might cause them to lose their vested interests. On a deeper level, there is also the fear that political system reform would shake the very foundation of one-party rule.

The editors of Political China, as well as Professor Jiang Ping and most of the authors of the articles in the book, were well aware of the sensitivity of political system reform, yet they discussed democracy, constitutionalism, the rule of law, and rights without self-censorship, demonstrating the integrity of the Chinese intellectual community.

However, the editors of Political China probably did not imagine that their worst fears at the time of publication would unfortunately come true: “As editors, we hope that the publication of this book can lay a useful groundwork for expanding the space for discussion on political system reform. If not, or if the opposite outcome occurs, then this by no means signifies merely the personal misfortune of the editors…”

Both editors of this book have long been active in the Chinese intellectual community, but both have suffered. Shi Binhai passed away in an accident in 2018, while Dong Yuyu, who has long advocated for constitutional reform, was persecuted for his words. In 2022, he was accused by the Chinese government of being a spy without any evidence and remains imprisoned to this day.

Several authors who contributed to Political China, including Jiang Ping, Li Rui, Zhu Houze, and Cai Dingjian, have passed away and did not live to see the day when China achieves democracy, the rule of law, and constitutionalism. Professor Cai Dingjian died young, leaving behind a famous saying: “Constitutional democracy is the mission of our generation.” It remains uncertain whether his dream will become a reality during the lifetime of his contemporaries.

The predicament into which China’s political situation has fallen and the misfortunes suffered by the Chinese people under this predicament have long been evident. Ultimately, the root cause of this misfortune is the ruling party and its specific vested interests’ refusal to sacrifice their own interests for reform. However, perhaps it is understandable that, under the grip of power, their self-interests are enormous. Their power is supreme, above the law, greater than the communist party’s constitution, and their wealth is astronomical. It can be said that this group at the top, which claims to “serve the people,” is the true master of China.

If the vested interests never choose to sacrifice their own interests, then is political system reform merely a theoretical concept? If this top-down political system reform has not occurred under the leadership of the Communist Party in the more than forty years since reform and opening up, what reason do we have to believe the same ruling elites can proactively change in the foreseeable future?

Political system reform, in the final analysis, is a top-down, conservative reform, with the power of life and death controlled by vested interests. The biggest advantage of this type of reform is peace, because it’s essentially not a revolution but an improvement, not a change of power, but an adjustment of the rules of redistribution by vested interests. In contrast, bottom-up change is very likely to cause people from all social strata—including the powerful vested interests—to pay a higher price.

This was also the common understanding of liberal scholars who once advocated for political system reform. Today, with the end of that period when reforms could still be discussed, and with those in power reversing historical progress, ordinary people are constantly paying the price for the injustices of the current system. Perhaps, when non-vested interest groups become increasingly unable to bear the cost of stagnant reform, the vested interests will also lose the opportunity for such top-down reforms. And the editors and authors of Political China, at that time, probably did not anticipate losing the option of political system reform.

Regardless of whether China’s future involves top-down reform or bottom-up change, if it is to achieve democracy, constitutionalism, the rule of law, and freedom, and establish a better political system, collective effort is indispensable. The two editors of Political China left a message for us today in their postscript written nearly thirty years ago:

“How can one imagine that the thinking of only dozens of brains, the writing of only dozens of pens, and the shouts from only dozens of mouths can achieve China’s political system reform? Even if we take a step back, if China’s political system reform could indeed succeed in the silent indifference of the public, then would those who experienced the process but did nothing feel ashamed before this achievement, ashamed before this era?”

We are now acutely aware of the consequences of silent indifference. Therefore, we need the thinking of more brains, the writing of more pens, and the voices of many more people to bring about change, to ensure that the predecessors’ exploration and contemplation of reform were not in vain, and to ensure that the cries of brave individuals like Mei Shilin and Peng Lifa can echo throughout China.

Recommended archive:

要是真到了危急存亡的时刻,这种声音就会在国内合法出现了