《炎黄春秋》杂志:一个体制边缘俱乐部的兴衰浮沉

Yanhuang Chunqiu Magazine: The Rise and Fall of a Magazine on the Margins of China's Political System

作者:海星

By Hai Xing

The English translation follows below.

一报《南方周末》,一刊《炎黄春秋》,曾几何时,这一南一北两大媒体,是中国改革开放年代的舆论重镇。可以说,他们曾经的光荣与梦想,实际上代表了改革开放年代的光荣与梦想;而他们后来的衰败乃至沉寂,也意味着这个时代的黯然落幕。

对这两家媒体来说,曾经,推动改革开放、推动中国的和平转型是它们共同的使命,但它们各自的定位、风格又不同。如果说南方周末主要从新闻专业主义的定位出发,来履行媒体之为社会公器的天职,那么《炎黄春秋》的政治性更强。现在终于可以说,它实际上不只是一家媒体,更是一个体制边缘的政治俱乐部。

政治元老们“去组织”的组织化尝试

正如毛泽东早年所言,“党外无党帝王思想,党内无派千奇百怪。”一个超大体量的执政党,政治和思想上的分化是必然的,但共产党作为高度中央集权的执政党,又绝不允许任何分化,任何公开的分化都会被认为是分裂党,都属于莫逆之罪。这种情况下,政党的分化就只能转为地下。

《炎黄春秋》就是这种党内分化的产物。幸逢改革开放时代,国内大气候相对宽松,不仅党内的不同声音能够有机会浮出水面,而且这些持不同声音的党内人士还可以有某种形式的自发集结,只是,这种集结不可表现为公开的组织化,也不能有任何明确的组织形式。

那么,不妨就用媒体及同仁刊物的形式。这就有了《炎黄春秋》。

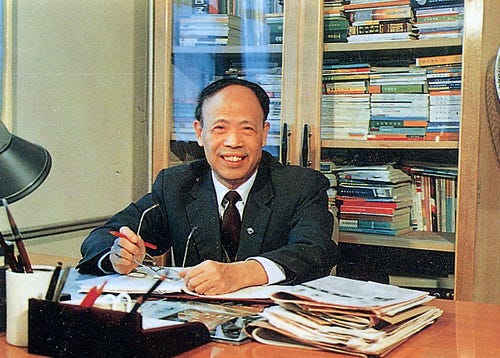

《炎黄春秋》公开的创始人和操盘人,是曾任国家新闻出版署署长的正部级高官杜导正。但实际上,杜主要是出头人,如果把《炎黄春秋》比喻成一个大企业,杜这位总裁之外,背后其实有个隐形的元老院。元老院的成员,绝大多数都是离退休的党内大佬。

最重要的人物是萧克。萧克是中共党内顶级元老,他是黄埔军校第四期毕业,曾参与南昌起义。25岁出任红八军军长,27岁出任红六军团军团长,其资历不在林彪、彭德怀之下。萧克因为跟毛泽东个人的紧张关系,中共建政后没能评上元帅,只评了个区区上将。但其德高望重,为党内军内公认。尤其是长期的边缘化,让他有足够空间冷静观察和反思,对体制有清醒的认识。

萧克不是一个人在战斗,中共党内有一批像他这样对体制有清醒认识的大佬,统称“两头真”老干部。所谓“两头真”,意思是他们早年怀着理想投身中共,以推翻国民党一党专政、建立民主新中国为奋斗目标,但中共建政后,他们也被裹挟,离初心越走越远。文革的十年浩劫让他们大梦初醒,重又走上了争取自由民主的道路。“何时宪政大开张”,这是曾任毛泽东兼职秘书的党内元老李锐的名言,也是这些“两头真”老干部共同的心声。

正是这批“两头真”老干部,构成了《炎黄春秋》隐形的元老院。萧克、李锐之外,参与创始的人还包括前国防部长张爱萍,前副总理田纪云,前人大副委员长、知名社会学家费孝通,以及张闻天曾经的秘书何方,前新华社副社长李普,前中国社会科学院副院长李慎之等。他们多数属于胡耀邦、赵紫阳两任总书记的旧部,在胡赵分别失势之后,他们成了胡赵思想遗产的主要守护者。

正是以他们为中心,残存的党内改革派、民主派聚集起来,开始形成某种力量。《炎黄春秋》某种程度上既是他们的机关刊物,也是他们合法聚集的平台,也可以说是一个俱乐部。

这不是政治组织,不属于政党或政派,但它又不是完全的无组织,而是一种非常接近临界点的组织化。在中国,任何媒体都必须有官方机构主管,《炎黄春秋》也不例外,为此,萧克于1991年5月专门创办了“中华炎黄文化研究会”,并出任首任会长,《炎黄春秋》即挂靠该会。该会其实就是一个明确的组织,只是不以政治而是以文化之名出现。也就是说,为了能够组织起来,萧克等一批“两头真”老干部,把自己的政治影响力和改革开放时代特有的灰色空间,用到了极致。

研究会问世仅两月,《炎黄春秋》即告创刊。此时,距离1989年天安门事件仅过去两年,中共正大举“反和平演变”,极左派极其猖獗,国内政治气候极其严酷,邓小平也还没有进行所谓的南巡。在这关头创办《炎黄春秋》,聚集改革力量,可见萧克等人的勇气智慧。

虽然《炎黄春秋》的创始人都是体制内高官,但杂志本身不属于体制内,它没有编制,人员全是聘用制;没有财政拨款或任何其他官费,费用都来自读者订阅;也没有官方提供的办公场地,都来自市场租赁;属于典型的市场化媒体,带有强烈的民间色彩。跟官方的联系,主要是创始人的身份以及因创始人的个人影响而拥有的官方特批的公开刊号。就此而言,《炎黄春秋》实际上处于一个亦官亦民的灰色地带。居于这样的体制内外结合部,一方面对体制内发言,影响体制内人士尤其体制内高层,另一方面对体制外的广大公众发言,影响社会。这正是创始人的初衷。

后来的历史证明,他们实现了自己的初衷,并与身处广州的南方周末形成某种微妙呼应。分处南北的一报一刊千里共舞,曾经持续为中国的改革开放鼓与呼。

常识的火种:从历史反思到自由启蒙

《炎黄春秋》对当代中国思想史作出了独特贡献,从以下几点可见。

首先是还原历史真相,尤其党史、国史的真相。这也是杂志创始人萧克的初衷。亲历者宋文茂回忆,萧多次这样强调:“历史就是历史,不能人为地歪曲事实。真理只有一个,是不能以某种政治上的需要来改变的。”“历史的事实是最大的权威。”“搞历史研究的同志必须求实存真,不能作违心之论。”

可以说,在中国的言论环境下,《炎黄春秋》最大限度贯彻了这些原则。

《炎黄春秋》虽然政治性极强,但主要表现形态还是一份文史刊物,自许“以主要篇幅记述重要的历史人物和重大历史事件”。而所涉重要历史人物和重大历史事件,大多数属于官史刻意掩饰甚至完全回避的敏感题材。如《延安时期的“特产”贸易》(2013年8月期,作者洪振快)一文,此处所谓“特产”即鸦片产业,这一段关于延安时期鸦片产业的历史,就是官史讳莫如深的一个黑洞。

从共产党建政之初到八十年代所谓“严打”,数十年的中国苦难史,《炎黄春秋》都没有回避,镇反、反右、文革等是其常规题材。此外,杂志也频频聚焦于一般媒体噤若寒蝉的其它高风险题材。

比如,披露土改真相的篇章有:《董时进致信毛泽东谈土改》、《土改中的蔡家崖的“斗牛大会”》、《晋綏土改中的酷刑》。

又比如对大饥荒真相的逼问。这方面《炎黄春秋》用心最多,可谓不遗余力。仅从2010年前后的一些文章标题,即可见一斑:《曾希圣是如何掩盖大饥荒的》;《大跃进中山东的两次饥荒》;《彭水县大饥荒人口非正常死亡报告》;《地方志中的广西饿死人事件》;《地方志中大饥荒死亡数字;一个生产队的死亡档案》;《大饥荒中农民的反应》;《驳饿死三千万是谣言》等等。

关键在于,这些文章往往出自权威人士或者亲历者手笔,极具可信度。而像这些颇具影响的重头文章,20多年下来,可谓不绝如缕,篇轶浩繁。

《炎黄春秋》的另一个贡献是思想启蒙,主要是对常识的普及,对自由、民主、法治等普世价值的启蒙。

如果说八十年代的主题是人道主义,那时人们刚刚走出宗教矇昧,人的觉醒,人的解放成为普遍渴望。九十年代的主题则是自由主义,正是从九十年代开始,自由主义在中国浮出水面。而《炎黄春秋》的灵魂人物之一李慎之,就是九十年代中国自由主义的扛旗人,他是一个风向标,代表一大批痛定思痛的“两头真”老干部,集体转向自由主义。自由、民主、法治等普世价值,由此构成《炎黄春秋》的底层逻辑。普及现代文明,普及常识,成了这份杂志的历史使命。

为此,《炎黄春秋》做出了持久的努力。从2010年前后的文章标题,即可见一斑:《论表达权与言论自由》;《重提如何保障宪法规定的出版自由》;《新闻自由在中国的命运》;《欧美征税权演变与政治文明》;《美国的党争》;《宪政民主应成为基本共识》等等,本文文末有更多列举。

《炎黄春秋》对中国当代思想传播的另一个贡献,是冒当时之大不韪,公开呼吁重新评价胡耀邦、赵紫阳。2005年11月,胡耀邦诞辰90周年,为配合纪念活动及胡之女李恒(满妹)的著作出版,《炎黄春秋》特意安排了“我们心中的胡耀邦”专题,请田纪云、李锐等多位党内元老发声。这与中国青年报《冰点》周刊同期发表的“我心中之耀邦”一文,彼此呼应,而令当局大怒,双双遭中宣部批评。该期杂志并被短暂封禁,后始复售。那之后,《炎黄春秋》冒着巨大阻力,依然频频发表赞颂胡耀邦的重磅文章。

在中国,有关前中共书记赵紫阳的话题,比胡耀邦的话题更为敏感,属于绝对红线,但《炎黄春秋》也要碰。2007年7月,前副总理田纪云在该杂志杂志发表重磅文章:《国务院大院的记忆》,对赵紫阳作了正面描述,称赞赵在担任国务院总理时倡导节俭、反对铺张浪费。当局禁止此文上网,同时禁止其他媒体转载。《炎黄春秋》没有停止,纪念赵的文章陆续又有发表。此举在大陆媒体界可谓绝无仅有。

个人认为,《炎黄春秋》之呼吁重新评价胡赵,主要目的并不在胡赵个人毁誉。《炎黄春秋》元老院的政治老人,无疑对胡赵深怀感情,但其冒险重新评价胡赵,主要还是基于政治考量而非仅仅怀旧,还是属意胡赵遗产,即胡赵代表的体制内改良主义路线。

由此延伸可知《炎黄春秋》的重要理念之一,即主张胡赵路线,实际上是要在当时主流的政治选择而外,试图给出新的政治选择,为中国的和平转型敞开新的可能性。

《炎黄春秋》的老人们推崇胡赵,但没有停留于胡赵,而是有很大发展。这表现为两点。第一是明确主张告别斯大林模式和所谓特色社会主义,向北欧社会民主党学习,于是有了2007年第2期,中国人民大学前副校长谢韬的重磅政论:《民主社会主义模式与中国前途》。文章认为马克思主义的最高成果是民主社会主义,民主社会主义寄托着人类的希望,只有民主社会主义才能救中国。此文一出,惊动中国思想界。第二是明确主张宪政社会主义。2011至2013年,《炎黄春秋》发表了多篇同一主题的政论。包括萧功秦《我看宪政社会主义》、何炼成《宪政社会主义要伸张民权》、童之伟《八二宪法与宪政》等。

在中国,关于宪政的讨论,比较有规模的出现于2008年,原本局限于法学界。《炎黄春秋》的高调参与,将宪政这一颇为敏感的议题,以及不同思想派别之间的争论,推送到大众面前,使其公共化,客观上在中国传播了民主宪政的思想。参与争论的,有强大官方背景的“反宪政派”,以及自由派知识分子为主体的欧美宪政派,还有主张在现有体制下推进宪政的“社会主义宪政”派,也即‘承认或不挑战中共长期执政的宪法正当性,以宪法逐项列举的方式明确党权范围,同时通过立法具体规范党权行使程序。”

在这场论战中,《炎黄春秋》站在社宪派(主张宪政社会主义)一边,反映了其体制内改良主义的基本立场。因为论争中向体制内外普及了宪政常识,引起当局高度紧张。2013年4月,风云突变,高层出面干预,宪政问题在中国的媒体上从此成为禁区,不再有讨论空间。

像这样主动介入意识形态的论战,在《炎黄春秋》其实不是第一次。2008年汶川地震后,全国范围批判普世价值,《炎黄春秋》却旗帜鲜明地支持普世价值,2009年5月发表了文化部元老高占祥的文章:《普世价值不可一概否定》,如此顶风而上,当局亦无可奈何。

《炎黄春秋》另一个重大贡献,是不懈地呼吁以宪政民主为方向的政治体制改革。仅作者不完全统计,从2001年到2016年《炎黄春秋》最后被关闭,呼吁宪政民主,呼吁政治体制改革的文章,就有五、六十篇。而在25年的存在历史中,《炎黄春秋》的此类文章更是洋洋大观。可惜,这样的努力并没有能够改变什么。当一个国家开起倒车,呐喊者也无能为力。

在这些相关文章中,最值得说道的,是2013年1月《炎黄春秋》的编辑部文章:《宪政是政治体制改革的共识》,强调政改是一场“维宪运动”,明显呼应稍前《南方周末》新年献词:《中国梦 宪政梦》。而正是这篇新年献词,引发了轰动中外的南周新年献词事件。《炎黄春秋》在此关键时刻挺身而出,声援南周同仁的同时,鲜明地亮出自己的旗帜。是为大勇。

还值得说道的是,那些文章的作者,很多都是当时中国知识界的泰斗,中国法学四老,除了重行而不重言的大律师张思之,其他三老,如郭道晖、李步云、江平,悉数出现在作者名单上,其时已年过八十的郭道晖先生更是连篇累牍,可见其执着,也可见其赤子之心。

厄运降临 :停刊是不可阻挡的宿命

如此定位,注定了《炎黄春秋》的命运。厄运之来,是迟早的事。

2008年之前,《炎黄春秋》的运行大体上还算平静。原因一是当时国内的政治环境相对宽松,二是一批政治老人都还在,尤其是萧克还在。最高当局纵有百般不快,也不得不忍。2008年10月24日,萧克将军去世,《炎黄春秋》的命运马上开始逆转。当年11月,文化部高层人士即出面劝社长杜导正退休,被拒。2009年5月22日起,《炎黄春秋》网站开始无法访问,直至5月31日才恢复正常。2013年1月4日9时左右,《炎黄春秋》网站更是被直接关闭。2014年9月10日,中共高层直接出面,强行改变杂志的主管单位。

与此同时,对《炎黄春秋》有组织的网暴也拔地而起。2015年,《国防参考》杂志刊发中国社科院马院研究员龚云的文章:《起底〈炎黄春秋〉》,指控《炎黄春秋》打着合法旗帜,假借客观公正之名,“对普通民众特别是离退休干部具有很大迷惑性和欺骗性”。文章还称,《炎黄春秋》“抹黑毛泽东,抹黑英烈,虚无历史,实际上是把新中国的历史颠倒过去,为把中国拉回资本主义做舆论准备”;此文在同年6月3日被解放军报的微博转载并引发激烈争议。这一切当然不是空穴来风,实际上都是舆论铺垫。

2016年7月,《炎黄春秋》杂志终于被官方全面接管。二十五年的历史到此画上句号。但相信其光荣与梦想不会就此终结,而会一直照耀后人,照亮自由事业的未竟之路。

(作者海星:居住于中国大陆。历史研究者,新闻从业者。)

本期推荐档案:

《炎黄春秋》——中国民间档案馆已收藏《炎黄春秋》在被官方接管前的全部期刊,欢迎读者们浏览、下载、收藏!

本文提及并推荐的炎黄春秋文章篇目:

关于普世价值:

《论表达权与言论自由》(2011-1 郭道晖);《建国前党对新闻自由的说法与做法》(2012-8 孙旭培);《重提如何保障宪法规定的出版自由》(2013-2 吴江);《新闻自由在中国的命运》(2013-4 孙旭培);《苏俄的新闻审查》(2013-5 李玉贞);《马克思捍卫新闻出版自由》(2014-9 安立志);《欧美征税权演变与政治文明》(2014-6 王建勋);《宪政审查的世界经验》(2012-9 张千帆);《瑞典违宪审查实践及启示》(2013-12 高锋);《民国的公民教育》(2012-4 毕苑);《美国的党争》(2012-5 董郁玉);《美国政治是金钱政治吗》(2014-9 张海平);《什么是法治》(2013-12 魏耀荣);《转型成功依赖公民社会成长》(2013-5 贾西津);《反思国有经济强国论》(2014-7 曹正汉);《宪法序言及其效力争议》(2013-6 张千帆);《百年宪政认识误区》(2013-5 王建勋);《美国宪法精神探求》(2013-3 张千帆);《党在法下——八二宪法的关键原则》(2013-4 黄钟);《蒋经国与台湾政治转型》(2013-3 王轶群);《台湾百年民主路》(2012-7 杭之);《西班牙民主转型之路》(2014-12 魏兴荣);《“非法之法”与公民抵抗权》(2013-2 郭道晖);《财税改革必须保障纳税人的权利》(2013-9 李炜光);《建设完备型税收国家》(2014-8 姚轩鸽);《自由是社会主义的核心价值》(2014-2 李光远);《宪政民主应成为基本共识》(2012-6 张千帆);《公民做什么》(2014-1 吴思)

呼吁宪政民主与政治体制改革:

《一定要解决好民主化问题》(2011-7 何方);《执政党必须在宪法和法律的范围内活动》(2011-7 郭道晖);《言论自由关系到党的兴衰》(2011-7 王海光);《还权于民、让利于民才能保障民生》(2011-7 张曙光);《守卫我党的政治伦理底线》(2011-7 周瑞金);《走出伪民主误区》(2011-10 许良英);《政治体制改革躲不开绕不过》(2011-11 虞崇胜);《实现由革命党到宪政党的演进》(2011-11 郭道晖);《上下互动,促进政治体制改革——本刊座谈会摘要》(2012-5);《“八二宪法”的回顾与展望》(2012-9 李步云);《政治体制改革应该中步前进了》(2012-9 杜导正);《依法治国依宪执政》(2012-12 洪振快整理);《规范执政党与人大的关系》(2012-12 郭道晖);《从党治走向法治》(2012-12李步云);《司法改革应向世界主流看》(2012-12 江平);《党内民主破局可从“三落实”入手》(2012-12 任剑涛);《政治体制改革是经济持续增长的前提》(2012-12 陈志武);《宪政是政治体制改革的共识》(2013-1 本刊编辑部);《四项基本原则有两个版本》(2013-2 刘山鹰);《宪法是政治体制改革的旗帜》(2013-3 高锴);《1988年深圳特区的政改方案》(2013-6 徐建);《法治要有几个大突破》(2013-9 李步云);《落实宪法贵在一个“诚”字》(2013-9 杜导正);《宪法的形成和落实有阶段性》(2013-9 吴思);《法治要有几个大的突破》(2013-9 李步云);《树立宪法权威必须追究违宪行为》(2013-9 郭道晖);《推进民主重在完善人大制度》(2013-9 蒋劲松);《人大代表制度要改进》(2013-9 蔡霞);《市场经济需要宪政》(2013-9 张维迎);《习仲勋建议制定〈不同意见保护法〉》(2013-12 高锴);《解放思想再出发》(2014-1 本刊编辑部);《建设自由社会的法治国》(2014.3 郭道晖);《1946年的宪政方案》(2014.3 刘山鹰);《冲破阻力,做全面改革的促进派——本刊新春联谊会发言摘要》(2014-4);《法治的关键是政体》(2014-6 艾永明);《政党执政模式决定党政关系》(2014-6 应克复);《政改要有开放的政治文化心态》(2014-6 韩云川);《司法中立,改善党的领导的关键》(2014-9 童之伟);《依宪治国是执政的基本守则》(2014-10 郭道晖);《邓小平与〈党和国家领导制度的改革〉》(2014-10 吴伟);《著名学者座谈四中全会决定,“权力入笼,必先”权利出笼“》(2014-12 郭道晖);《法治国家的标准与建设思路》(2014-12 李步云);《重大改革于法有据与新问题〈(2014-12 江平);《改革要从司法突破》(2014-12 何兵);《领导干部干预案件的问题如何解决》(2014-12 刘仁文);《向法治中国迈进》(2015-1 本刊编辑部);《依宪执政五人谈——依法治国与保护不同意见》(2015-8 江平);《党和国家领导制度的改革》(2015-8 邓小平);《我为何建议重发邓小平“8.18”讲话》(2015-8 李锐);《大刀阔斧推进法治——田纪云忆乔石》;《良法 良知良序》(2015-8 张千帆);《民主是绕不过的坎》(2014-12 张千帆);《邓小平“8·18”讲话的现实意义》(2015-10 陈剑);《政权的合法性系于民心向背》(2015-10 皇甫欣平);《宪法应为人民所掌握》(2016-1 郭道晖);《从人治到法治的历程》(2016-6 郭道晖)

Yanhuang Chunqiu Magazine: The Rise and Fall of a Magazine on the Margins of China's Political System

By Hai Xing

One newspaper, Southern Weekly, and one magazine, Yanhuang Chunqiu—these two major media outlets, one based in southern China and one based in northern China, were once central pillars of public discourse in the era of China’s reform and opening-up. One could say that their past glory and aspirations actually embodied the glory and aspirations of the reform era itself; their subsequent decline and eventual silence signified the fading of that era.

For these two media outlets, promoting reform and peaceful transition in China was once a shared mission, though their positioning and styles were different. If Southern Weekly primarily approached its mission from the standpoint of journalistic professionalism, fulfilling the media’s role as a public instrument, then Yanhuang Chunqiu was more politically oriented. Now, we can finally say that it was not merely a media outlet, but rather a political club situated on the margins of China’s political system.

An Attempt at Organizing Without Formal Organization by Political Elders

As Mao Zedong once said, “No parties outside the Party is imperial thinking; no factions within the Party is sheer fantasy.” For an extraordinarily large ruling party, political and ideological divisions are inevitable; but the Chinese Communist Party, as a highly centralized ruling party, does not permit any such division—any open divergence is regarded as party-splitting and a grievous offense. In this context, any internal division within the party can only go underground.

The magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu was a product of this kind of intra-party division. It arose during the era of reform and opening up, when the domestic atmosphere was relatively relaxed—not only could differing voices within the Party surface, but these dissenting voices could even spontaneously congregate in some form; however, such a collection could not be presented as open organization, nor could they take on any clearly defined organizational form. So then, why not use the form of a media outlet or a peer-edited journal? Thus came the magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu.

The publicly acknowledged founder and operator of Yanhuang Chunqiu was Du Daozheng, a minister-level official who once headed China’s General Administration of Press and Publication. But in reality, Du was mainly the public face; behind Du stood an invisible council of elders, whose members were mostly retired senior figures from within the Party.

Among them, the most important figure was Xiao Ke. Xiao Ke was a top-level Party elder; he graduated from the fourth class of the Whampoa Military Academy and participated in the Nanchang Uprising. At 25, he became commander of the Red Eighth Army; at 27, he led the Red Sixth Army Corps—his credentials were no less than those of Lin Biao or Peng Dehuai. Due to personal tensions with Mao Zedong, Xiao Ke was not granted the title of Marshal after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, but was given only the rank of General. However, he was highly respected and widely recognized within both the Party and the military. His long marginalization gave him the space to calmly observe and reflect, resulting in a clear understanding of the system.

Xiao Ke was not fighting alone. Within the Party there was a group of similarly clear-eyed senior figures who joined the Communist Party with idealistic hopes of overthrowing the Kuomintang’s one-party rule and building a democratic New China. However, they deviated from their idealism after the founding of the People’s Republic. After the Cultural Revolution, which served as a rude awakening, they once again embarked on the path of pursuing freedom and democracy. “When will constitutional governance truly begin?”—this famous line by Party elder Li Rui, once Mao’s personal secretary, encapsulated the shared hope of these Party elders.

It was precisely this group of veteran cadres who constituted the invisible council of elders behind Yanhuang Chunqiu. In addition to Xiao Ke and Li Rui, other founders included former Minister of Defense Zhang Aiping, former Vice Premier Tian Jiyun, former Vice Chairman of the National People’s Congress and renowned sociologist Fei Xiaotong, He Fang (former secretary to Zhang Wentian), former Deputy President of Xinhua News Agency Li Pu, and former Vice President of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Li Shenzhi. Most of them were former subordinates of General Secretaries Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. After Hu and Zhao fell from power, these individuals became the principal custodians of their ideological legacy.

Centered around these figures, the remnants of the reformist and democratic factions within the Party gradually regrouped and began to build influence. In many ways, Yanhuang Chunqiu served both as their house publication and as a legitimate platform for them to gather. One could also call it a kind of club.

This was not a political organization, nor did it belong to any party or faction. But it was not completely unstructured either. In China, all media must be overseen by an official sponsoring body, and Yanhuang Chunqiu was no exception. To meet this requirement, Xiao Ke established the “Chinese Yanhuang Culture Research Association” in May 1991 and became its first president. Yanhuang Chunqiu was officially affiliated with this association. In reality, the association was a formal organization, though it appeared under the banner of culture rather than politics. In other words, to organize themselves, Xiao Ke and the other elders used every ounce of their political capital and the unique gray space afforded by the reform era.

Just two months after the founding of the association, Yanhuang Chunqiu launched its first issue. At that time, only two years had passed since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. The Communist Party was in the midst of a major campaign against “peaceful revolution,” far-left ideologues were rampant, and the domestic political climate was extremely harsh. Deng Xiaoping had not yet undertaken his southern tour, which eventually restarted economic reforms. In such a moment, to establish Yanhuang Chunqiu and rally reformist forces was a testament to the courage and wisdom of Xiao Ke and his peers.

Although the founders of Yanhuang Chunqiu were all high-ranking officials within the system, the magazine itself was not part of the system. It had no formal staffing quotas—its personnel were entirely on contract. It received no state funding or government subsidies; all costs were covered by reader subscriptions. It had no government-provided office space; all premises were rented from the market. It was a quintessentially market-driven publication, with a distinctly grassroots character. Its only official connection lay in the identities of its founders and the special government-approved publication license granted through their personal influence. In this sense, Yanhuang Chunqiu operated in a gray zone—neither fully official nor fully unofficial.

Occupying this liminal space between the system and civil society, it spoke to both realms. On one hand, it communicated with those inside the system, influencing especially those in the upper echelons of power; on the other hand, it addressed the general public outside the system, shaping broader social discourse. This was precisely the magazine’s founding vision.

Later developments would prove that they had realized this vision. Together with Southern Weekly based in Guangzhou, Yanhuang Chunqiu formed a subtle resonance. One newspaper in the south and one magazine in the north—working in tandem across the country—were once an enduring force advocating and rallying support for China’s reform and opening-up.

The Spark of Common Sense: From Historical Reflection to the Enlightenment of Freedom

Yanhuang Chunqiu made several unique contributions to the intellectual history of contemporary China. One such contribution to contemporary Chinese intellectual history was its effort to recover historical truth, especially regarding the history of the Communist Party and the Chinese nation. This mission aligned with founder Xiao Ke’s original intention. According to memoirs by those who worked with him, Xiao repeatedly emphasized that history must not be distorted by political needs: “History is history. It cannot be deliberately twisted. There is only one truth, and it should not be changed to serve political ends.” He believed that historical fact was the highest authority, and that historians must seek truth and speak sincerely.

Given the constraints of China’s speech environment, Yanhuang Chunqiu pursued these principles to the greatest extent possible. Though highly political in essence, the magazine presented itself primarily as a publication of culture and history, with the stated aim of documenting significant historical figures and events. However, the subjects it chose to focus on were often the very topics that official government historiography either downplayed or ignored altogether. For instance, a 2013 article titled “The ‘Specialty Product’ Trade During the Yan’an Period” by Hong Zhenkuai addressed the Communist Party’s opium trade in Yan’an—an aspect of history the state has long refused to acknowledge.

From the founding of the Communist Party’s rule to the so-called “strike hard” campaigns of the 1980s, spanning decades of suffering in China’s history, Yanhuang Chunqiu never shied away from covering these topics. Regular subjects included the suppression of counterrevolutionaries, the Anti-Rightist Campaign, and the Cultural Revolution. In addition, the magazine frequently focused on other high-risk topics that most mainstream Chinese media avoided.

For example, chapters revealing the truth about land reform include: “Dong Shijin’s Letter to Mao Zedong on Land Reform,” “The ‘Bullfighting Spectacle’ at Caijiaya during Land Reform,” and “Torture during the Jin-Sui Land Reform.”

Another example is the persistent inquiry into the truth about the Great Famine. In this area, Yanhuang Chunqiu was especially diligent and relentless. Just looking at some article titles around 2010 gives us a glimpse: “How Zeng Xisheng Covered Up the Great Famine,” “Two Famines in Shandong during the Great Leap Forward,” “Report on Abnormal Deaths during the Great Famine in Pengshui County,” “Starvation Deaths in Guangxi Recorded in Local Chronicles,” “Death Figures in Local Chronicles during the Great Famine: A Production Team’s Death Records,” “Farmers’ Reactions during the Great Famine,” and “Debunking the Argument that 30 Million Starvation Deaths is a Rumor.”

The key point is that these articles were often written by authoritative figures or firsthand witnesses, lending them high credibility. Over more than 20 years, these influential and major articles appeared continuously and abundantly.

Another major contribution of Yanhuang Chunqiu was its role in popularizing basic principles of political liberalism: freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and constitutional governance.

If the 1980s in China were characterized by a renewed interest in humanism—after decades of ideological indoctrination—then the 1990s marked the emergence of liberal thought. One of the magazine’s spiritual leaders, Li Shenzhi, became a key symbol of this liberal turn. A former senior government adviser, Li had once supported the regime but later became a vocal advocate for democracy and universal values. His transformation reflected a broader shift among many Party elders.

From this turn, Yanhuang Chunqiu developed a coherent liberal-democratic ethos. It promoted common sense and civic education. Articles in the early 2010s include: “On Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Speech,” “Revisiting Constitutional Guarantees of Freedom of Publication,” “The Fate of Press Freedom in China,” “Taxation and Political Civilization in the West,” “American Partisanship,” and “Constitutional Democracy Should Be a Basic Consensus.”

The magazine was also one of the few Mainland Chinese publications that openly called for a reassessment of Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang—two former Communist Party leaders who had been ousted for their reformist leanings. In 2005, on the 90th anniversary of Hu Yaobang’s birth, the magazine ran a commemorative issue titled “Hu Yaobang in Our Hearts,” featuring tributes from several Party elders including Tian Jiyun and Li Rui. This echoed a similar article in China Youth Daily, and both pieces were harshly censured by the Central Propaganda Department. That issue of Yanhuang Chunqiu was briefly banned but later allowed to resume publication. Since then, despite the pressure, Yanhuang Chunqiu continued publishing articles praising Hu Yaobang.

Discussions of Zhao Ziyang, the former Premier and General Secretary who opposed the 1989 crackdown, were even more sensitive than the mentions of Hu Yaobang, but the magazine did not shy away. In 2007, Tian Jiyun published an article titled “Memories from the Courtyard of the State Council” in Yanhuang Chunqiu praising Zhao and recalling Zhao’s efforts to promote frugality and combat waste. The article was banned from the internet and other media were prohibited from reprinting it, but Yanhuang Chunqiu continued to publish other articles honoring Zhao in subsequent years—an unprecedented move in the mainland media landscape.

In my view, Yanhuang Chunqiu’s call for a re-evaluation of Hu and Zhao was not primarily driven by concerns for their personal reputations. While the political elders undoubtedly harbored deep affection for Hu and Zhao, their risky re-evaluation was primarily based on political considerations rather than mere nostalgia. They were ultimately interested in preserving the Hu-Zhao legacy—that is, the intra-system reformist line represented by Hu and Zhao.

Extending this, one of Yanhuang Chunqiu’s crucial tenets was its advocacy for the Hu-Zhao legacy. In essence, it sought to offer a new political alternative beyond the prevailing mainstream choices of the time, thereby opening up new possibilities for China’s peaceful transformation.

The elders of Yanhuang Chunqiu revered Hu and Zhao, but they did not stop there; they significantly expanded upon their ideas. First, they explicitly advocated for bidding farewell to the Stalinist model and the so-called “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” instead suggesting learning from Northern European social democratic parties. This led to the powerful political commentary by Xie Tao, former Vice President of Renmin University of China, titled “Democratic Socialism and China’s Future,” published in the second issue of 2007. The article argued that the highest achievement of Marxism is democratic socialism, that democratic socialism embodies the hope of mankind, and that only democratic socialism can save China. Upon its publication, this article caused a stir in Chinese intellectual circles. Second, they explicitly advocated for constitutional socialism. From 2011 to 2013, Yanhuang Chunqiu published several political commentaries on this same theme, including Xiao Gongqin’s “My View on Constitutional Socialism,” He Liancheng’s “Constitutional Socialism Should Promote Civil Rights,” and Tong Zhiwei’s “The 1982 Constitution and Constitutionalism.”

In China, discussions about constitutionalism emerged on a relatively large scale around 2008, initially confined to the legal community. Yanhuang Chunqiu’s high-profile involvement brought the rather sensitive issue of constitutionalism, and the debates among different ideological factions, to the public, thus popularizing the idea of democratic constitutionalism in China. Participants in the debate included the “anti-constitutionalism faction” with strong official backing, the “European and American constitutionalism faction” primarily composed of liberal intellectuals, and the “socialist constitutionalism” faction. The latter advocated for advancing constitutionalism within the existing system by acknowledging or not challenging the constitutional legitimacy of the Communist Party’s long-term rule, explicitly defining the scope of Party power through itemized listing in the constitution, and simultaneously specifically regulating the exercise procedures of Party power through legislation.

In this debate, Yanhuang Chunqiu sided with the constitutional socialist faction, reflecting its fundamental position of intra-system reformism. Because the debate popularized constitutional common sense both inside and outside the system, it did not initially trigger extreme alarm among the authorities. However, in April 2013, the situation abruptly changed; high-level intervention occurred, and the topic of constitutionalism in Chinese media became a forbidden zone, with no further room for discussion.

This kind of proactive intervention in ideological debates was not a first for Yanhuang Chunqiu. After the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, when universal values were widely criticized nationwide, Yanhuang Chunqiu conspicuously supported universal values, publishing an article by Gao Zhanxiang, an elder of the Ministry of Culture, in May 2009 titled “Universal Values Cannot Be Completely Denied.” Despite such open defiance, the authorities did not react.

Another significant contribution of Yanhuang Chunqiu was its unremitting call for political system reform in the direction of constitutional democracy. Based on incomplete statistics, from 2001 until Yanhuang Chunqiu was finally shut down in 2016, there were fifty to sixty articles advocating for constitutional democracy and political system reform. Over its 25-year history, the magazine published a vast number of such articles. Regrettably, these efforts ultimately failed to bring about change. When a nation begins to regress, even the loudest voices are rendered powerless.

Among these related articles, one of the most noteworthy is Yanhuang Chunqiu’s January 2013 editorial, “Constitutionalism is the Consensus for Political System Reform.” This piece emphasized that political reform is a “movement to uphold the constitution,” clearly echoing Southern Weekly’s New Year editorial, “The Chinese Dream, the Constitutional Dream.” It was this very Southern Weekly editorial that ignited wide debate. Yanhuang Chunqiu bravely stepped forward at this critical moment, not only supporting its Southern Weekly colleagues but also boldly displaying its own convictions. This was an act of great courage.

It is also worth noting that many of the authors of these articles were leading intellectuals of China at the time. Among the “four elders of Chinese jurisprudence,” besides the highly action-oriented but less vocal lawyer Zhang Sizhi, the other three elders—Guo Daohui, Li Buyun, and Jiang Ping—all appeared on the list of authors. Mr. Guo Daohui, who was over eighty at the time, even wrote numerous articles, demonstrating his unwavering dedication.

The Arrival of Misfortune: The Inevitable Fate of Closure

Its distinctive positioning ultimately determined the fate of Yanhuang Chunqiu. Its downfall was merely a matter of time.

Before 2008, Yanhuang Chunqiu generally operated relatively peacefully. This was partly due to the more relaxed domestic political environment at the time and partly because a number of political elders, particularly Xiao Ke, were still alive. Even if the highest authorities were deeply displeased, they had to exercise restraint. On October 24, 2008, General Xiao Ke passed away, and the fortunes of Yanhuang Chunqiu immediately began to reverse. In November of that year, senior officials from the Ministry of Culture advised Director Du Daozheng to retire, but he refused. From May 22, 2009, the Yanhuang Chunqiu website became inaccessible until it resumed normal operation on May 31. On January 4, 2013, around 9 AM, the Yanhuang Chunqiu website was directly shut down. On September 10, 2014, high-level Communist Party officials directly intervened, forcibly changing the magazine’s supervising unit.

Concurrently, an organized online smear campaign against Yanhuang Chunqiu magazine erupted. In 2015, National Defense Reference magazine published an article by Gong Yun, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Marxism Institute, titled “Exposing Yanhuang Chunqiu.” The article accused Yanhuang Chunqiu of operating under a legal banner and using the guise of objectivity and fairness to “greatly mislead and deceive ordinary people, especially retired cadres.” It further claimed that Yanhuang Chunqiu “vilifies Mao Zedong, vilifies heroes, and nihilizes history, effectively overturning the history of New China and preparing public opinion for pulling China back to capitalism.” This article was retweeted by the People’s Liberation Army Daily’s Weibo account on June 3 of the same year, sparking intense controversy. All of this was, of course, a deliberate influence of public opinion.

Finally, in July 2016, Yanhuang Chunqiu was completely taken over by the authorities. Its twenty-five-year history came to an abrupt end. Yet its glory and aspirations do not end there—they continue to illuminate the path ahead, a beacon for the unfinished cause of freedom.

Recommended archives:

Yanhuang Chunqiu (The China Unofficial Archives has collected all issues of Yanhuang Chunqiu from 1991 to 2016. Readers are welcome to read and download the PDFs.)