从《我向总理说实话》到《工厂》:城乡二元体制下的集体创伤

From I Speak the Truth to the Premier to “Factory”: Collective Trauma Under China’s Urban-Rural Divide

作者:阳玉

By Yang Yu

The English translation follows below.

近年来,关于农民、农民工及其二代、小镇青年的话题,在中国青年亚文化社区——如Z世代的精神家园Bilibili,吸引了大量的创作者,成为说唱、鬼畜(一种影音混剪形式)、二次元创作的热门之一。最具代表性的,要属去年“河南说唱之神”的重磅单曲《工厂》,以及今年6月开始在B站大火的“亚细亚旷世奇才”的《莫愁乡》。

这两首歌讲述的都是在农村与城市之间流转的年轻一代的集体性创伤。衰败的乡村,污染严重的环境,对故乡“我没有热爱这里,我只是出生在这个地方”的感情,想要离开故土去城市寻找更好生活,以及对城乡差异中人们不公命运的含蓄质疑。可以说,这两首歌精准表达了一代乡镇青年的情感和经历,由此而刺痛了无数人的心,还在B站上激起了层出不穷的二次创作。而几乎每首歌的评论区,都成了千禧年到Z世代的乡镇青年——不管是留在村里的,或是进城打工的,以及考上大学离开村庄的人的哭墙。似乎因为这两首歌的存在,他们经历的伤痛终于有了出口、有了形态。

但今天听《工厂》和《莫愁乡》、为自己的创伤寻找体认和共鸣的Z世代农村青年,可能很难知道,20多年前的中国,曾经有一本叫《我向总理说实话》的书,以充分的数据和来自现实的第一手观察和分析,揭示了中国社会扎心的一面:农民在中国的现实体制安排下,确实是作为“二等公民”的存在——就如学者杜润生所说的,中国农民始终没有得到自己的国民待遇。借助于2000年前后中国社会关于“三农”(农民、农村、农业)问题的广泛讨论,这本书曾经让中国不公平的城乡二元体制之弊真实地呈现在世人面前。

乡村何以成为进城青年自卑感的来源?

2000年中国官方人口的统计数据显示,中国居住在乡村的人口有80739万人,占总人口的63.91%,而2025年人口数据信息显示,乡村人口为46478万人,占总人口的33%——这说明,近20多年来,又有30%的人口从农村转移到了城市。而这些人大部分都是2000年前后出生、现在是劳动主力的青年。

这些人在农村出生,后来又以农民工或大学生的身份进入城市,他们在城市化浪潮中长大,已经成了所谓“城里人”,但又永远无法和在城市出生的人一样。乡村是他们难言的隐痛、抛不开的包袱、自卑感的来源,以及区别于真正的“城里人”的身份标记。

二十多年过去了,农村青年成为了城里人,什么变了,什么没变?为什么在中国,农村出生地、农村户口,以前是,现在依旧是社会公认的、根深蒂固的一个人主要的身份标记?为什么“凤凰男”这种带有明显歧视意味的标签到现在都在中国社会如此有效地通行?为什么直到2021年,一个农村的中学生,在公开演讲中表达的励志话语是:“我就是一只来自乡下的土猪,也要立志去拱了大城市里的白菜!”?为什么《工厂》和《莫愁乡》会火?为什么有那么多人在评论区里哭泣?

只要你在中国生活,就知道中国社会对农民的情感充满悖论。主流话语对农民,以及与之相随的苦难、贫穷、忍耐和劳动一直予以赞美,但现实却是没有城里人想成为农民,也没有农民想让自己的后代成为农民。农村孩子的人生目标,依然是脱离农村,最好永不回来。即使那些已进入城市,受了良好教育并找到工作的人,农村出身这个标签依然可能相随他们一生,“凤凰男”、“凤凰女”的说法始终提醒着他们的低人一等。

为什么会这样?是哪里出了问题?20多年前的中国,在媒体和思想界,那一场深入和广泛的讨论——“三农问题大讨论”中,对今日乡镇青年感受的创伤与不公正感的根源——中国城乡二元体制的存在,就提出了深入的质疑与追问。

中国的“城乡二元体制”多年来备受诟病。这一体制基于1949年后中共实施的计划经济体制,其核心是城乡户籍制度,国家明确将居民分为农业人口和非农业人口,把城市与农村人为分割开来,资源配置向城市绝对倾斜,城市人口相对农村人口,也拥有各种特权与福利——这一切导致乡村成为城市的附属,农民成为“二等公民”,在经济、文化各方面,城乡之间都有巨大的壁垒。

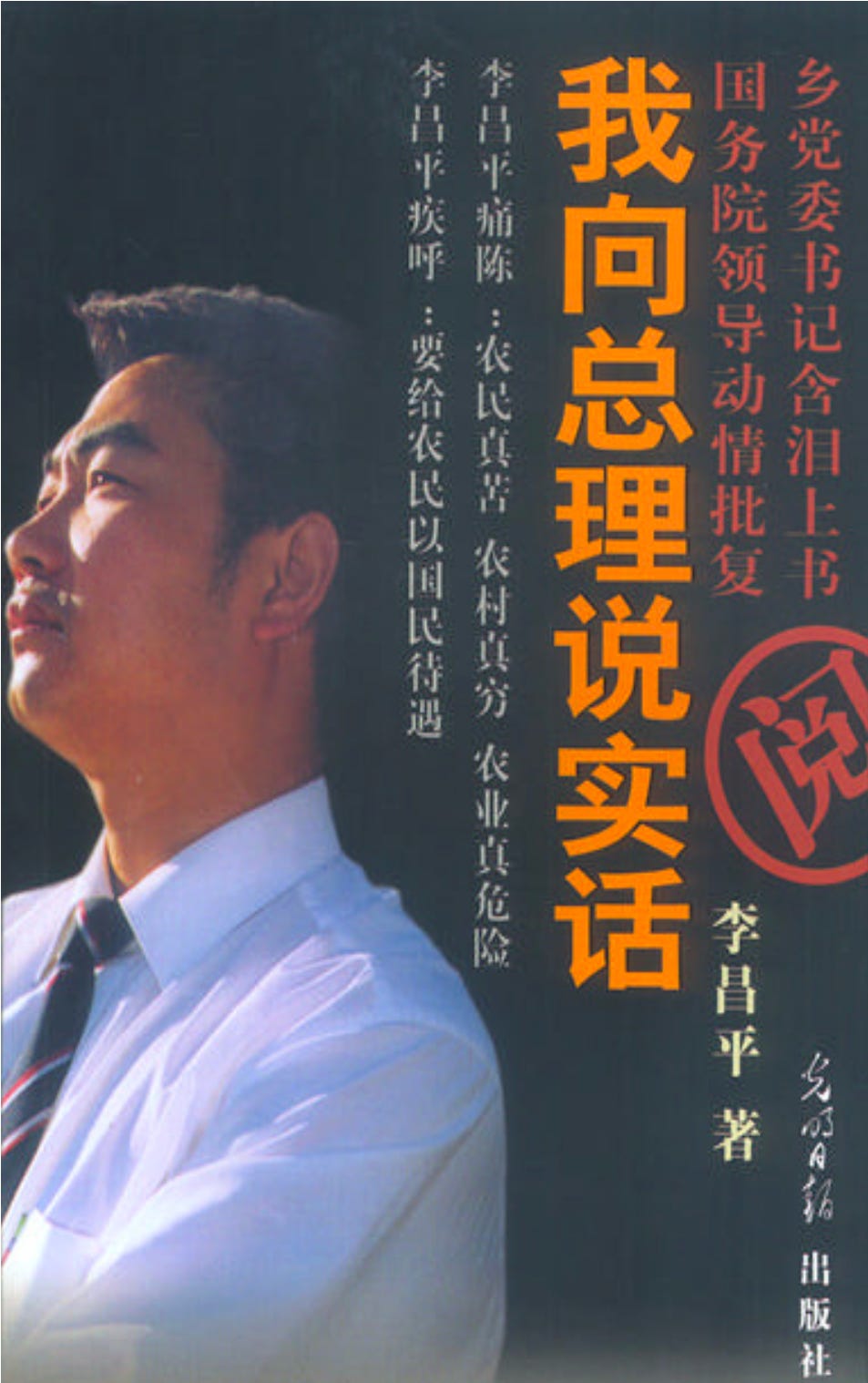

2002年由光明日报出版社首次出版,2009年再版的一本书——李昌平的《我向总理说实话》,就代表着这样的质疑与追问。李昌平——这位农村出生的乡镇党委书记的经历记录,为中国的农村叙事提供了一种难能可贵的真实。而且,这种真实既关于农村个体生存经验,更基于制度性的现实反思。

李昌平出生于湖北省监利县周河乡洪湖边的一个小渔村,后从中南财经大学经济学硕士毕业。1983年1月到2000年9月期间,他担任乡镇党委书记、县农村工作部副部长等职,几乎经历了1978年改革开放后的农村改革全过程。2000年3月,他致信当时的总理朱镕基,论述农村基层政治经济制度的弊端以及解决办法,引起中央对农村问题的关注,而他本人也因为这一封信带来的影响,最终难以在官场待下去,后辞去监利县棋盘乡党委书记的职务,南下成为一名打工者。

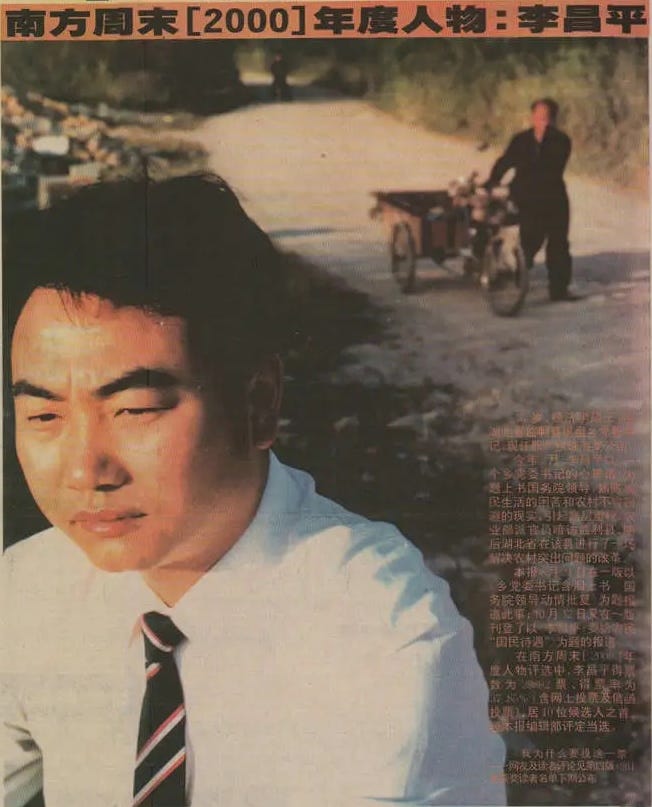

惊心的中国农村现实与基层政治生态

2000年10月,李昌平在媒体发表文章呼吁“给农民以同等国民待遇”,12月,他当选《南方周末》2000年年度人物——当年同在选列的人有著名导演王家卫、作家张平、中国加入世贸组织的谈判代表龙永图,联想集团CEO柳传志,前女足运动员孙雯等人。《我向总理说实话》一书因为影响力巨大,催生了2000年代初的中央农业改革措施,以及最终在2005年被全国人大审议通过的“废止千年农业税”的草案。

书中摘录的网友对李昌平当选2000年《南方周末》年度人物的评论,很能说明李能当选的原因:

“奥运冠军是我们需要的,娱乐是我们需要的,科技进步是我们需要的,财富更是百姓追求的,但是和这一切相比,一个健康、公正、自信而且充满理性的社会,才是培育这一切生长的乐土。”

这精准表达了中国人的心声——长久的城乡不公,必须得到改变,农民不应该是这个国家的二等公民。

《我向总理说实话》一书,主要论述的是农村现实问题,但李昌平作为一名基层干部,直接处于农民、农村和官僚政治系统之间,其对乡镇问题的一手经验,也非常难得地展现了中国基层政治生态的肌理。他的视角和经验,切实说明了为什么腐败是一个专制政治系统里必然会出现的问题;而农民的生活,甚至于生命,怎样被现行的政治经济制度规定、剥削、定义;农民在现实和政治经济系统层面,又究竟被如何区别对待?

他的书还涉及这些议题:城乡二元制度在城市和乡村如何运转;外出打工的人要交多少钱,才能拿到城市居留证;农民一亩地的平均收入有多少,地方粮站怎么规定粮价;农民每亩地要交多少土地承包费,人头费(书中所说的“出生在集镇,就不要人头负担,出生在农村就年年交人头费几百元”);农业税、屠宰税、宅基地使用费、结婚登记费、准生证费、外出打工费等等。这些名目众多的税费有多少钱?占农民收入多少?而农民又常常遭遇怎样的暴力征收?

在中国的城乡二元体制之下,农民到底承担了什么?

关于暴力,本书还涉及收容遣送制度下的农民工如何迁徙,外出打工的农民工在遣送站为什么会被虐待,甚至致死(2003年的孙志刚事件并不是个例),农村信用社的贷款政策实际如何操作,乡镇干部怎样雇佣地方黑帮流民暴力收税——以及那些因交不起税而自杀的人究竟有多少。事实上,这些遭受虐待或自杀的人数,从来就没有被记录下来。农民承受的苦难总是被一笔勾销,不仅不被记录,也缺乏任何反思——农民头顶那“自然而然”的权力究竟从何而来?这本书中,不仅有对农村现实的描摹,更可贵的,也透露着这样的疑问。

顾名思义,书的题目来自于李昌平给时任总理朱镕基的信,书中讲了很多李昌平自己的经历——如他小时候的饥荒时期,曾亲眼看到四岁的妹妹被老鼠咬死。除了在农村的所见所感,他还记录了“写信”的整个经过,以及他和农村问题专家的谈话和接受采访的访谈内容,还有他本人对于农村问题的整体性论述。因为李昌平本人的经济学背景,他在农村经历、观察的写实记录中注入了罕有的制度性分析——包括随处可见的经济数据举例和研究——于是在他的记录里,农村苦难的“理应如此”,“自然而然”得以被打破,得以被研究,得以被实实在在地看到——1978年实行家庭联产承包责任制后,改革开放中的农村和农民到底经历了什么?他的疑问如下:

为什么“1997年后,农民收入增幅连续四年下降,不到4%,普通农民人均收入增长是个负数,出现种粮亏本的局面”?

为什么农民进城打工,不仅要交城市里的各种费用,还要交农民户口的人头负担?

为什么城市的水电路基础设施由国家包办,而农村的基础设施是农民自己出钱出力?

农民在中国政治系统和经济政策中,在城乡二元制中,到底承担了什么?

为什么农民作为公民,却不被赋予平等的公民权力,甚至被限制迁徙的自由?“为什么他们就不能享受现代文明那些物质和精神的愉悦”(书中引语)?

中国农村问题专家杜润生在给本书写的导言中说道:

“李昌平不是第一个提出‘三农’问题的人,但以一个乡党委书记身份,系统提出、用数据说话、用切身经历讲话的,他是第一个。他告诉我们:除了在走向繁荣文明的北京、上海、广州、深圳等地方看到的中国,还有另外一个中国是乡土中国。”

与李昌平在本书收录的文章《给农民以同等国民待遇》中呼吁的一样,杜润生在序中倡导,解决三农问题涉及中国深层的政治经济体制问题。第一步应该是给农民以国民待遇,还农民以基本权利——因为对农民的论述,不仅关于农民,更关于中国建立公民社会的基础。

正视系统性歧视的现实 ,看到真实的农村和真实的人

作为一个普通公民,李昌平给朱镕基的信,因为是写给国家总理,其实也反映了当时中国民间的政治改革诉求。这封信到达了朱镕基手里后,引发了一系列来自上层的对李昌平的查访。李在信的末尾曾说:

“我确认自己无罪,确认自己有承受说实话的风险和资本,才敢把这封给总理的信发出去。一个人讲真话真的不容易,是一个非常痛苦的过程。讲真话竟像下地狱一样。”

正如李本人预料的,事件结尾是,李因为来自更为直接的上层政治压力,离任乡党委书记,从此没有再踏入政界。随着李的离职,他所向往的那些改革也并未有效进行,但因为他所说的实话,今天的人们,才能在主流国家叙事之外,看到改革开放时期的农民,依然在受到了怎样的制度性侵害,而对农民歧视的制度性来源到底在哪里——农村不是天然就应该贫困,农民就应该没有权利,而是这个国家的制度设计让他们被如此对待。

如果一个国家的制度没有平等地对待人,那这个社会的个体,很快会内化这种制度性歧视——而个体对这种内化的歧视常常缺乏自我意识,渗透到社会交往、认知的方方面面,具有根深蒂固的普遍性,于是,结构性歧视构成这个社会人人都生活在其中的现实。

人们需要《活着》,需要《许三观卖血记》,需要对苦难的讲述,也需要分析,需要宏观的认识,需要历史和记忆。上海大学说唱社团对农民工讨债的戏谑和侮辱,不是个例,是人对社会系统性歧视的内化。当人们对上海大学说唱团体在互联网上热烈地口诛笔伐的时候,并没有意识到自己本身也是这个歧视系统中的一部分。

如果我们无法系统性地认识城乡二元制的实践方式,及其对当代中国社会整体认知的造就,那不论如何热烈、积极地批评上海大学的说唱团体都没有什么意义。《工厂》的表达其来有自,新的并不新,旧的也并不旧——20年过去了,李昌平给朱镕基说的实话,听到的人并不多。从《工厂》这首歌曲带来的巨大共鸣就知道,李昌平在25年前关注到的农民境遇的不公,今天依旧在现实中延续。

《工厂》下的哭墙,有人听到吗?当几亿人的记忆和他们被系统性剥削和歧视的经历,依然被官方媒体上浩浩荡荡地赞美农民的语言覆盖、抹去,我们怎样才能看到真实的农村,真实的人?或许,是时候重读李昌平的这本书了。

本期推荐档案:

相关资料:

From I Speak the Truth to the Premier to “Factory”: Collective Trauma Under China’s Urban-Rural Divide

By Yang Yu

In recent years, topics concerning rural residents, migrant workers and their children, and small-town youth have garnered significant attention within China’s subculture youth communities, particularly the video platform Bilibili, a virtual home for Gen Z. These subjects have inspired numerous creators, becoming popular themes for rap music, kichiku (a type of audio-visual remixing), and anime creations. Two prime examples include “Factory” by Henan Rap God, which gained immense popularity last year and remains a top-five creator on Bilibili, and “No More Worries, My Hometown” by Asian World-Class Prodigy, which has been a major hit on Bilibili since June of this year.

Both rap songs narrate the collective trauma experienced by a young generation navigating life between the rural and the urban. They depict decaying villages, heavily polluted environments, and a sense of detachment from their hometowns, captured by a famous line from “Factory”: “I don’t love it here; I was just born in this place.” The songs convey a desire to leave their hometowns for better urban opportunities, implicitly questioning the unfair destinies arising from the urban-rural divide. These works precisely articulate the emotions and experiences of a generation of small-town youth, profoundly resonating with countless individuals and sparking a wave of secondary creations on Bilibili. The comment sections of almost every song have transformed into a wailing wall for China’s small-town youth, ranging from millennials to Gen Z, whether they remained in their villages, moved to cities for work, or left for university. It seems that through these songs, their previously unacknowledged pain finally found an outlet and took on a tangible form.

However, many Gen Z rural youths who listen to “Factory” and “No More Worries, My Hometown” today might be unaware that over two decades ago, a book titled I Speak the Truth to the Premier revealed similar truths about Chinese society. This book, supported by extensive data and firsthand observations, revealed how rural residents were effectively treated as second-class citizens under China’s existing institutional arrangements. As the scholar Du Runsheng noted, Chinese rural residents have consistently been denied the rights and treatment afforded to other citizens. Through widespread societal discussions around the year 2000 concerning the “three rural issues”—rural residents, countryside, and agriculture—this book starkly presented the flaws of China’s unjust urban-rural dual system to the public.

Why Is the Countryside a Source of Inferiority for Young Urban Migrants?

Official Chinese population statistics from 2000 indicated that 807.39 million people lived in rural areas, comprising 63.91% of China’s total population. By 2025, rural population data shows this figure dropping to 464.78 million, or 33% of China’s total population. This significant shift reveals that over the past two decades, another 30% of China’s population has moved from rural to urban areas. The majority of these young migrants were born around 2000 and now constitute the majority of China’s labor force.

These young migrants, born in the countryside, moved to cities as workers or university students. They grew up amidst the wave of urbanization and have become city dwellers, yet they can never truly be on par with those born in cities. The countryside remains an unspoken source of pain, an inescapable burden, a stigma of inferiority, and a defining characteristic that distinguishes them from true urbanites.

Twenty years have passed. Rural youth have become urban residents. What has changed, and what has not? Why do a rural birthplace and rural hukou (Chinese household registration) remain deeply ingrained and socially recognized primary identity markers in China? Why is the clearly discriminatory label “Phoenix Man,” which refers to a rural-born man making it in the city but hoping to advance by marrying a city girl, still so prevalent in Chinese society? Why, as recently as 2021, did a rural high school student’s motivational public speech declare, “I am just a pig from the countryside, but I am determined to pig out on the cabbages in the big cities!”? Why did “Factory” and “No More Worries, My Hometown” become so popular? Why were so many people weeping in the comment sections?

Anyone living in China probably understands the paradoxical emotions Chinese society holds toward rural residents, especially peasants. While mainstream discourse consistently praises peasants for their suffering, poverty, endurance, and labor, the reality is that no city dweller aspires to be a peasant, nor does any peasant wish for their children to follow their own path. The life goal for rural children remains to leave the countryside, ideally never to return. Even those who have moved to cities, received a good education, and found employment may find their rural background a lifelong label, with epithets like “Phoenix Man” and “Phoenix Woman” constantly reminding them of their perceived lower status.

Why does this persist? Where did things go wrong? Two decades ago in China, the discussions on the “three rural issues” in media and intellectual circles questioned and explored the root causes of the trauma and injustice felt by today’s small-town youth: the existence of China’s urban-rural dual system.

A pivotal book representing this inquiry was Li Changping’s I Speak the Truth to the Premier, first published in 2002 by Guangming Daily Press and reprinted in 2009. Li Changping, a rural-born township Communist Party secretary, offered a rare and authentic narrative of China’s rural realities. This authenticity stemmed from not only individual rural experiences but also a profound reflection on institutional realities.

Born in a small fishing village by Honghu Lake in Zhouhe Township, Jianli County, Hubei Province, Li Changping later earned a master’s degree in economics from Zhongnan University of Economics and Law. From January 1983 to September 2000, he served in various roles, including township party secretary and deputy head of the county’s rural work department, witnessing nearly the entire rural reform process following the reform and opening up in 1978. In March 2000, he wrote to then-Premier Zhu Rongji, outlining the flaws of the rural political and economic system and proposing solutions. This letter drew central government attention to rural issues. However, the fallout from his letter ultimately made it difficult for him to continue his government career, leading him to resign as party secretary of the Qiupan Township Party Committee in Jianli County and move to Shenzhen to become a migrant worker.

The Political Landscape of Grassroots China

In October 2000, Li Changping published an article in the media advocating for equal treatment for rural residents as Chinese citizens. In December, Li was named the magazine Southern Weekend’s Person of the Year 2000, beating out notable figures such as director Wong Kar-wai, writer Zhang Ping, China’s WTO negotiation representative Long Yongtu, Lenovo Group CEO Liu Chuanzhi, and female footballer Sun Wen. Due to its significant influence, I Speak the Truth to the Premier spurred agricultural reform measures in the early 2000s, which culminated in the abolition of the millennia-old agricultural tax in China in 2005.

The book includes Internet users’ comments on Li Changping’s selection as Southern Weekend’s Person of the Year in 2000, which illustrate the reasons for his recognition: “Olympic champions are what we need, entertainment is what we need, technological progress is what we need, and wealth is certainly what the people pursue. But compared to all this, a healthy, just, confident, and rational society is the fertile ground for all this to grow.” This statement accurately articulated the aspirations of many Chinese people—that long-standing urban-rural inequality must be addressed, and rural residents should not be treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

While I Speak the Truth to the Premier primarily discusses rural issues, Li Changping’s position as a local cadre, directly situated between rural residents and the bureaucracy, offered a rare firsthand account of the intricate workings of China’s grassroots political ecology. His unique perspective and experiences illustrate why corruption is an inevitable problem within an autocratic political system. He effectively demonstrated how rural residents’ lives, and even their very existence, are regulated, exploited, and defined by the prevailing political and economic system, and precisely how they are systematically subject to second-class treatment.

His book also explored issues such as: how the urban-rural dual system operates in both cities and rural areas; the fees migrant workers must pay for urban residency permits; the average income of rural residents per mu (667 square meters) of land and how local grain stations set grain prices; the amounts rural residents paid in land contract fees per mu and head taxes (as described in the book, “born in a market town, no head tax burden; born in a rural area, pay hundreds of yuan in head tax every year”); and the numerous taxes and fees, including agricultural tax, slaughter tax, homestead usage fees, marriage registration fees, birth permit fees, and migrant worker fees. The book questioned the total amount of these various taxes and fees, their proportion of rural residents’ income, and the frequent violence rural residents faced during their collection. Most of these fees would later be eliminated, in part because of efforts like Li Changping’s.

What Burdens Do Rural Residents Carry Under China’s Urban-Rural Dual System?

Regarding violence, the book also details the experiences of migrant workers under the custody and repatriation system, explaining why they were often abused and even died in repatriation stations (the infamous Sun Zhigang incident in 2003, which ignited an uproar and led to subsequent reforms, was not an isolated case). The book described the practical operations of rural credit cooperative loan policies and how township cadres employed local gangs and vagrants to violently collect taxes, even leading to suicides among those unable to pay. These instances of abuse and suicide, disturbingly, were never officially recorded. The suffering endured by rural residents was frequently dismissed, not only undocumented but also lacking any genuine reflection. The book implicitly asks: where does the seemingly natural and unquestioned authority over rural residents truly originate? Beyond depicting rural realities, the book’s greater value lies in posing this profound question.

As its title suggests, the book’s name is derived from Li Changping’s letter to then-Premier Zhu Rongji. The book includes many of Li Changping’s personal experiences, such as witnessing his four-year-old younger sister being bitten to death by rats during a famine. In addition to his observations and feelings in the countryside, he meticulously documented the entire process of writing the letter, his conversations with rural experts, interview transcripts, and his comprehensive analysis of rural issues. Li Changping’s background in economics allowed him to infuse his realistic accounts of rural experiences and observations with a rare institutional analysis, including numerous examples of economic data and research. This analytical rigor challenged the notion that rural suffering was “rightfully so” or “natural,” enabling it to be examined and truly understood: what exactly did the rural areas and rural residents experience during the reform and opening up period after the implementation of the household contract responsibility system in 1978? His key questions included:

After 1997, why did the percentage increase in rural residents’ income decline for four consecutive years to less than 4%, resulting in negative per capita income growth for ordinary rural residents and losses from grain farming?

Why did rural residents entering cities for work have to pay not only various urban fees but also a “head tax” due to their rural hukou? (The hukou is a way of dividing China’s population into urban and rural residents. The classification is hard to switch.)

Why was urban water, electricity, and road infrastructure provided by the state, while rural infrastructure required rural residents to contribute their own money and labor?

What burdens did rural residents truly bear within China’s political system and economic policies, and under the urban-rural dual system?

Why were rural residents, as citizens, not granted equal civil rights and even had their freedom of movement restricted? As quoted in the book: “Why could they not enjoy the material and spiritual pleasures of modern civilization?”

Du Runsheng, a Chinese rural issues expert, stated in his introduction to the book:

“Li Changping was not the first to mention the ‘three rural issues,’ but he was the first to systematically present them as a township party secretary, using data and personal experience. He showed us that beyond the China seen in places like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, which are moving towards prosperity and civilization, there is another China that is the rural China.”

Echoing Li Changping’s call in his essay “Give Rural Residents Equal National Treatment,” which the book includes, Du Runsheng advocated in his preface that resolving the “three rural issues” involves addressing deep-seated problems within China’s political and economic system. The crucial first step, he argued, should be to grant rural residents equal national treatment and restore their fundamental rights, because the discourse on rural residents is not merely about their well-being but about the very foundation of building a civil society in China.

Seeing the Real Countryside and the Real People

Li Changping’s letter to Zhu Rongji reflected the political reform demands of Chinese society at the time. After this letter reached Zhu Rongji, it prompted a series of top-level investigations into Li Changping. At the end of his letter, Li had written:

“I am sure I am not guilty, and I am sure I possess the risk-bearing capacity and resources to speak the truth, which is why I dared to send this letter to the Premier. For a person to speak the truth is truly difficult; it is an extremely painful process. Speaking the truth felt like descending into hell.”

As Li himself anticipated, it all ended with his resignation as township party secretary due to direct political pressure from higher authorities, and he never re-entered politics. With Li’s departure, the reforms he championed were not effectively implemented. However, it is precisely because he spoke the truth that people today can, outside the mainstream national narrative, understand the institutional abuses rural residents continued to face during the reform and opening up period, and precisely where the systemic roots of discrimination against rural residents lie. It highlights that rural poverty and the denial of rural residents’ rights are not natural but rather a consequence of China’s institutional design.

If a country’s system fails to treat people equally, individuals within that society will quickly internalize this systemic discrimination. This internalized discrimination often operates without self-awareness, permeating all aspects of social interaction and cognition, becoming deeply ingrained and pervasive.

People need novels like Yu Hua’s To Live or his Chronicle of a Blood Merchant, which narrate suffering. They also need analysis, a macroscopic understanding, history, and memory. The mocking and insulting rap lyric by a Shanghai University student group last year about migrant workers begging for unpaid wages is not an isolated incident; it exemplifies the internalization of systemic discrimination in Chinese society. Even though many people vehemently condemned the rap lyrics, they often fail to recognize their own participation within this discriminatory system.

If we cannot systematically understand the practical application of the urban-rural dual system and its profound impact on contemporary Chinese society, then our criticism of overt discrimination like the insulting rap lyrics will be futile. The message in “Factory” has deep historical roots; what seems new is not truly new, and what is old is not truly outdated. Twenty years have passed, and the truth Li Changping conveyed to Zhu Rongji was heard by very few. The immense resonance of “Factory” demonstrates that the injustice in rural residents’ plight, which Li Changping highlighted 25 years ago, persists today.

Is anyone listening at the “wailing wall” beneath “Factory”? When the memories of hundreds of millions of people, and their experiences of systemic exploitation and discrimination, are still overwritten and erased by the sweeping, praising language of China’s official media, how can we truly see the real countryside and the real people? Perhaps, it is time for us to reread Li Changping’s book.

Recommended archive:

Li Changping, I Speak the Truth to the Premier

Related materials:

Henan Rap God, “Factory”

Asian World-Class Prodigy, “No More Worries, My Hometown”