我与林昭(上篇): “她走上了夏瑜的道路” (顾雁回忆录选登)

“She Chose a Martyr’s Path”: Lin Zhao and Me (Part 1) (Selected Excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoirs)

顾 雁 口述/修订

艾晓明 撰稿/整理

Narrated & revised by Gu Yan

Written & compiled by Ai Xiaoming

The English translation follows below.

编者按:

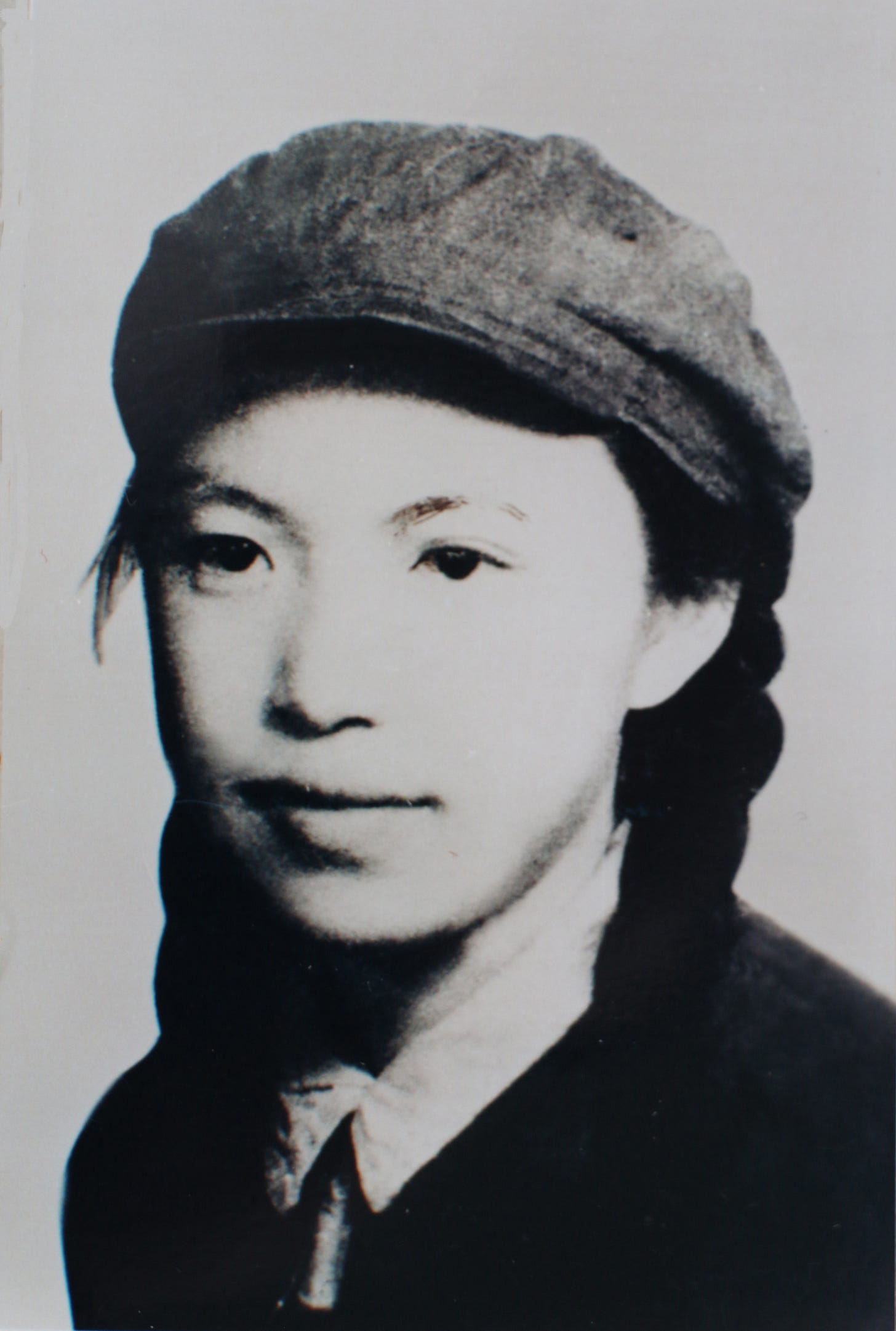

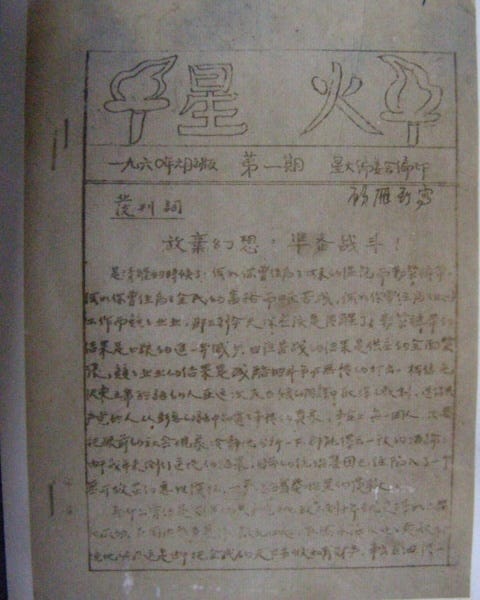

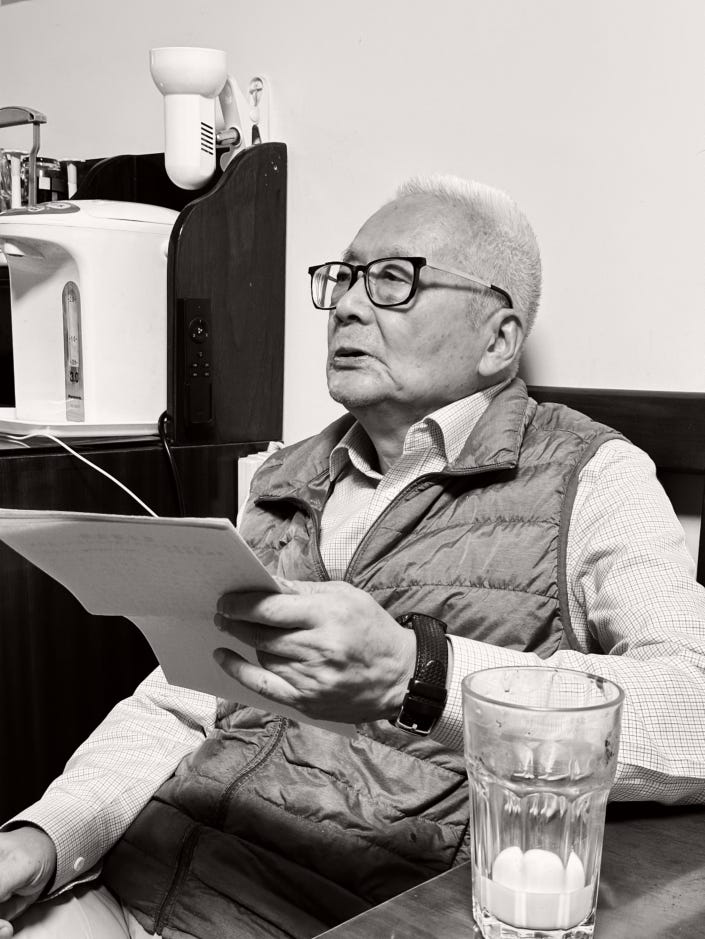

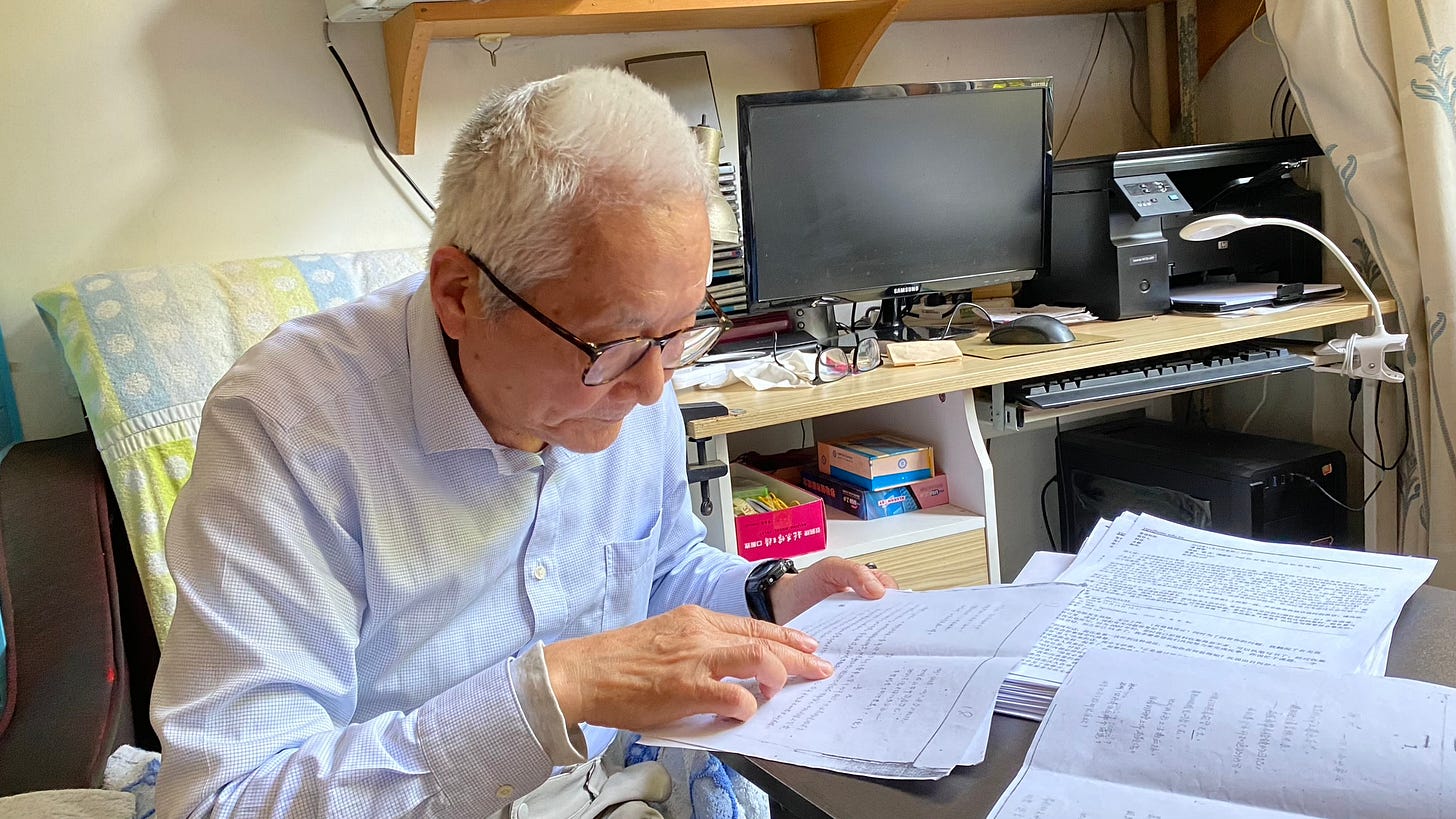

大饥荒时期地下刊物《星火》的创刊人顾雁教授,于2025年8月23日度过了他的九十岁生日。顾雁一生坎坷,1960年因“星火案”在上海被捕,与林昭、梁炎武同案,1965年被判处17年徒刑,后到青海服刑,1980年平反后到兰州大学任教,与顾淑贤结为伉俪。顾雁于2001年从中国科技大学退休,是理论物理研究专家,著有《量子混沌》一书,现居合肥。

顾雁在北京大学物理系读书时,与长他三岁的林昭(中文系新闻学专业学生)并不相识。1959年《星火》在天水秘密创刊前,顾雁曾亲手刻印林昭的长诗《海鸥》,在朋友们之间散发,并将她的另一首诗刊发在《星火》第一期上。1960年他回上海探亲期间,与林昭见面,后频繁往来三、四个月,两人之间产生情愫,往来信件数十封,后顾雁、林昭先后被捕。林昭取保候审,重被收监后遭遇非人折磨,于1968年4月29日惨遭杀害。

本文是艾晓明教授编撰整理的《顾雁回忆录》之一部分,分上、下两篇。耄耋之年的顾雁在其中详细回顾了自己与林昭的交往,以及林昭与《星火》的关系等。这是自《星火》诞生66年以来,作为创始者的顾雁首次以第一人称,对自己一生经历,以及“星火往事”的一次全面回顾。其中他与林昭之间的情感、囚禁中听闻她已牺牲的“悲痛惭愧”,都感人至深。作为亲历者和见证者,顾雁的回忆,也有极高的历史价值。

中国民间档案馆得以首次刊发,深感荣幸。

另外,关于本文题目——夏瑜是鲁迅笔下的革命者,原型为秋瑾。林昭被杀害后,正在青海服刑的顾雁得知消息,悲痛不已,在和家人通信中,因高压审查而无法表达心情,只能暗示说“她走上了夏瑜的道路”。

前记:

到2025年4月29日,林昭遇难已经五十七周年。二十六年前,林昭的闺蜜倪竞雄就曾约我写一篇纪念林昭的文章,一直没有成文。这些年里,我接受过胡杰、傅国涌、吴明卫、江雪的采访,回复过胡杰、依娃、谭蝉雪关于林昭的来信,都是围绕着同一个话题——我与《星火》、与林昭的关系。

我与林昭分别于1960年秋天,此后作为同案,同时被起诉、判决。我活下来了,林昭遇难,一起创办《星火》的难友张春元牺牲。我们相识时都才二十多岁。耄耋之年,写下这段记忆,是幸存者的责任,也是我的夙愿。

我认识林昭,缘起于林昭的诗《海鸥——不自由毋宁死》,我们的案情与《星火》相关,后来的命运一度交织在一起。

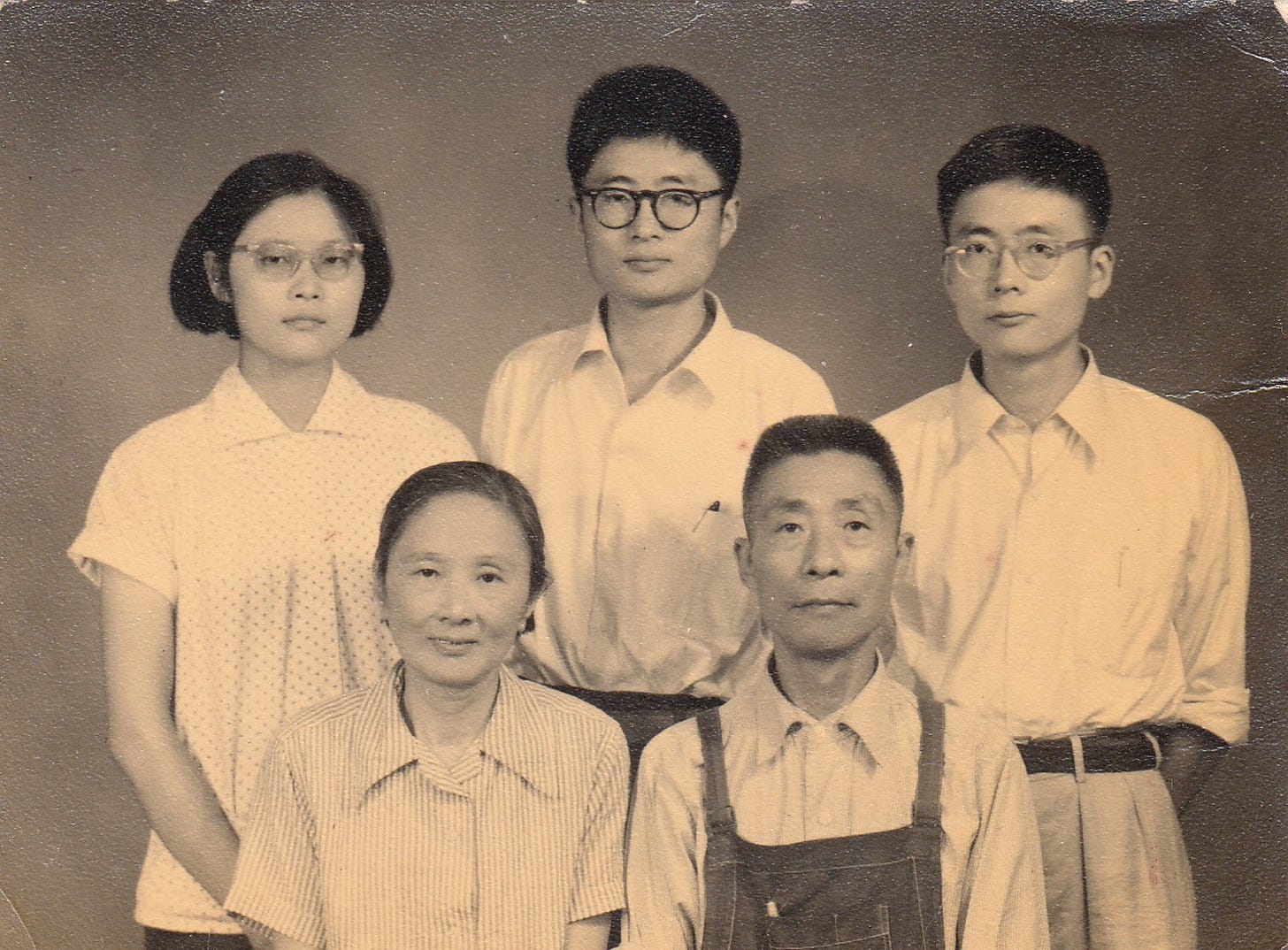

我大哥顾鸿和妹妹顾麋也因为我与林昭受到牵连,他们在“文革”中,几乎陷入灭顶之灾。

很多研究林昭和《星火》案的人,都把林昭看作《星火》的创办人之一,这不符合事实。林昭与我和张春元,的确有思想共鸣。我和她的私谊,更是终生难忘。但我未曾加入校友、同龄人对林昭的回忆里,也是因为我对一些事情,有不同的看法。倒是我妹妹顾麋还写过一篇纪念文章,是我妹夫李惠康代为执笔的。

还有一件触动我的事,是北大校友张元勋在回忆中写到的经历。1966年5月6日,林昭在北大中文系的同学张元勋去提篮桥监狱探视林昭。见面时林昭对他说:“我随时都会被杀,相信历史总会有一天人们会说到今天的苦难!希望你把今天的苦难告诉给未来的人们!并希望你把我的文稿、信件搜集整理成三个专集:诗歌集题名《自由颂》,散文集题名《过去的生活》,书信集题名《情书一束》。”

林昭写给我的信,至少有三十封以上。在她短暂的一生中,给我写的信,应该是最多的。如果要编《情书一束》,需要从我们的案卷里,将当年搜走的信件提取出来。我希望将来上海市静安区法院的档案开放,我能收回我和林昭之间的全部书信。

一、我刻印了林昭的《海鸥》

与林昭见面之前,我先读到了她的诗稿《海鸥——不自由毋宁死》(以下简称《海鸥》),印象中大概是在1959年的4月或5月,张春元在狱中交代的是暑假期间,即7月、8月,也有可能我记得不准确。

诗稿是通过孙和传来的,孙和是上海人,他妹妹孙复是林昭的同班同学。张春元从孙和手里拿到了这首诗,他传给我看;我那时已经在天水二中教物理了。读到这首诗,受到诗中那种正气的感染,也很喜欢。我说:“我们把这首诗刻印下来。”为什么要刻印?也是因为想分享给几位好友。我在钢板上刻好蜡纸,在马跑泉的拖拉机站印了若干份。张春元是站长,他一个人一个办公室,油印工具都是他办公室的。

半个世纪后,谭蝉雪在天水终于找到《星火》案卷,其中就有这首诗。谭蝉雪拿到以后与我核对,她问我:“案卷中的《海鸥》是不是林昭的笔迹?”

我说:“这是我的笔迹。”她说:“这是案卷里的材料,怎么可能是你的笔迹?”我说:“这本身就是油印的,原始的诗稿在张春元那里。”看到复印件上的字迹,我马上就认出来了,因为是我排的版,我刻的。

为《海鸥》写《跋》的作者,署名鲁凡。谭蝉雪问我:“鲁凡是谁?”我告诉她,是张春元用的笔名,他当时跟我讲:“鲁迅已走,把走之底去掉,就成了凡字。”张春元《跋》的文字也是学鲁迅笔法,他交给我《海鸥》这首诗的时候,已经写了《跋》。

张春元肯定了《海鸥》诗中那种“头可断志不可屈”的精神,同时他也认为“不自由毋宁死”的号召是“显得浮夸了”。他觉得,不应该沉浸在伤感的情绪里,而应该依靠集体的力量去行动。为了保护林昭,规避风险,他有意将落款时间写为1949年五四前夜,并说明:“诗的作者系一青年学生,有志于文艺事业,曾于两年前学生运动高潮中,因误会被当局逮捕,后下落不明。”这些说法,都是为了转移视线。

我将《海鸥》印好后,张春元发给了在天水一起劳动考察的右派同学,具体是哪些人,我就不清楚了。最初,林昭的诗和《星火》没有直接的关系,因为《星火》的创刊是后来的事情。

【根据张春元狱中交代文字:1959年9月,孙和至西宁归来后,经孙复的介绍,孙和开始与原在人民大学工作的林昭通信,并收到林昭寄来的长诗《海鸥》。同年9月至10月,在天水东泉拖拉机站,以张春元为主油印了几篇文章,计有《论粮食问题》《毛主席给全国农村党员干部的一封信》《海鸥》《替曹操翻案幕后》等。艾晓明注。】

林昭还有一首诗,《普罗米修士受难的一日》,那首不是我刻的。这两首诗中,我先读到了《海鸥》。

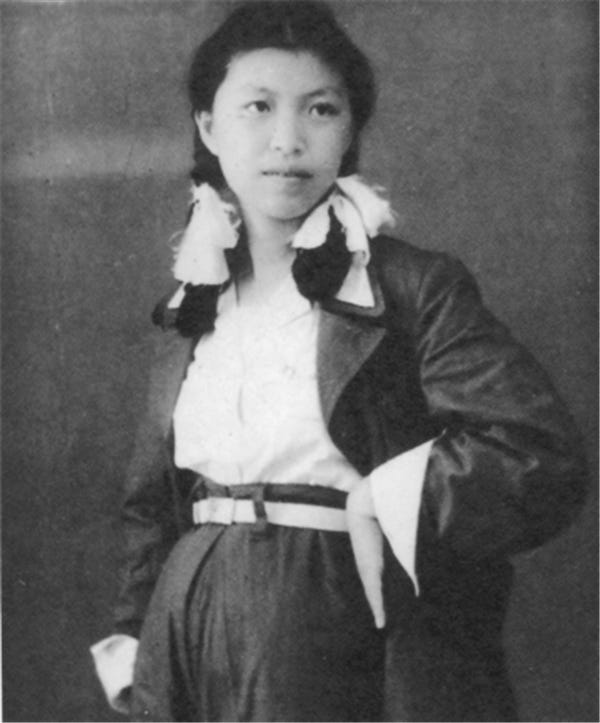

在北大,我比林昭早入学两年,我是1952级,她是1954级。林昭是调干生,有工作经历,年龄也比我大两三岁。在北大时我还不认识她,但知道她是个有名的人物。我后来跟林昭讲,我那时要碰到你,你看也不会看我一眼。你看她在北大拍的照片多神气,就是这样一个人,谁都瞧不起。

印完《海鸥》不久,张春元要去上海出差。他跟我商量,说他要去找林昭。张春元从孙和那里拿到林昭的地址,直接去了茂名南路的159弄11号,并把我们刻印的《海鸥》和《跋》带给了林昭。

可能两人谈得投机,思想有共鸣,林昭主动把近期写的诗给了张春元。诗是写在浅蓝色信笺纸上,整页的信笺纸被裁成了八分之一大小,数页装订在一起,可以直接放入口袋。这个小册子外观精致,林昭的笔迹秀丽,给我留下极深的印象。

这首长诗就是《普罗米修士受难的一日》,林昭借用希腊的神话故事,表达了“我不入地狱谁入地狱”的牺牲精神。我想,她也许是要告诉我们,她并不像我们想象中的那样消极。

1959年11月,我、张春元、苗庆久和胡晓愚四人在北道埠的一个旅社里聚会,商议创办《星火》。我说,把普罗米修斯这首诗收进去。原稿应该是由苗庆久带回了武山,他当时主动提出,刻印《星火》的事由他负责。

1959年12月,决定刻印《星火》后,我们这群人就兵分两路了。这时的离散并非是有明确的行动计划,主要还是现实所迫,各人有对自己出路的考虑。苗庆久、胡晓愚分别留在武山和天水,我回到了上海。谭蝉雪已经回到广西,张春元也准备回河南。

因此可以说,林昭并没有参与筹划和创办《星火》。她与《星火》这个刊物的关系,主要就是这两首诗。而这两首诗,也不是她主动要求我们刻印出来,而是我们自己做主印出来的。所以林昭被捕以后,她还说我“侵犯”她的版权嘛。的确,我刻印《海鸥》时,和她连面也没见过,当然也不可能征求她的同意。

【林昭:“在分局,很早,承办员就问到过我关于顾雁印了‘海鸥’的事。我叫先不知道,只好由着生米煮成熟饭,若早知道,决不同意!——不用说别的,就作为原作者,我也有不同意的权利,‘海鸥’有些叛徒情绪,但也不过是叛徒情绪罢了,不值得一印,不能给别人多少东西。”——《个人思想历程的回顾与检查》(1961年10月14日),以下林昭相关引文,均出自林昭在上海市第二看守所写下的这篇文章。】

有关林昭、张春元和我共同创办《星火》的说法,流传甚广,但不是事实。2003年,倪竞雄寄给我一份《林昭年表》,我看到这个说法后,曾通过倪竞雄转了一封信给编者,要求更正。然而我的信如石沉大海,没有得到任何回音。其后我发现,在《走近林昭》(2007年,明报出版社)附录的《林昭年表》中,编者仍坚持此说。

回顾这段历史,应该说,林昭没有直接参与《星火》的具体策划,但她的两首诗对我和张春元的思想认识,对《星火》的诞生有直接的影响。至少,这使我们俩都认识到,在中国的土地上,确实还有一些青年朋友,他们愿意为改变不合理的现实而牺牲。

二、“‘两只脚’来找你了”

1959年底,我以养病的名义回到上海。住在我家的老房子“德星堂”里,用“顾羽”这个假名字报上了户口。

临走时张春元告诉我,见到林昭时用暗语,这是他与林昭约定的,听到这个暗语便知道是我,具体的暗语是什么,我现在记不起来了。

因为读过林昭的诗,我对林昭是非常尊敬的。1960年1月初,我就是怀着这种心情来到茂名南路159弄的二楼,敲响了她的家门。

林昭开的门,她知道是我后,便让我去附近的复兴公园等她。这是我和她的第一次见面,我带去了刚印出来的《星火》第一期,其中刊有她那首长诗《普罗米修士受难的一日》。离开天水时,我从胡晓愚那里拿到五份《星火》,一份给了我的北大同学梁炎武——此时他也被打成右派,另一份给了林昭。余下的三份,后来被静安分局搜走了。

几天后,林昭来信,约我到中山公园会面。这次她带来一本吕思勉的《中国近代政治思想史》,她说自己正在读这本书,写得很好,借给我读一下。这天在公园里,她向我讲了些民国年间的名人轶事,也说了她本人的大致情况,却只字未提我带给她的《星火》。我也未敢径直询问。

从这时起,到我当年10月18日被捕,我们有九个月的交往。在林昭家里,我有个外号叫“两只脚”。林昭妈妈应该是见过我的,林昭没有正式地介绍我。我找林昭,她出来后,我们就一起下楼了。我比林昭高,她妈妈在后面,就看见我的两只脚。因为这个印象,我去后,她就问林昭:“是不是两只脚又来找你了?”

在那九个月里,我和林昭见面十多次,书信来往不下数十封。她从未与我谈及对《星火》的评价。她没有问过我是如何成为右派的,我也未问过她有关《红楼》与《广场》之事。在后来的会面中,她甚至从不主动谈及严肃的政治和思想理论问题。我曾多次向她提到我和张春元计划中的活动,我不是在乡下印东西吗?我希望她能出些主意甚至参与进来,我感觉,林昭都有意回避了。

张春元来上海也直接找过她,希望她加入我们的行动。那么她对张春元是怎么表态的,我不清楚。张春元讲过,他也看得出来,林昭不太想加入我们这一伙。我觉得这很自然:你们两个人她倒是认识,你们后面还有一大批人,她完全不认识。我明确地意识到,她想和我们的团体活动保持距离。这无疑使我对她有些失望,但我也完全能理解。

大概是1960年3月,张春元到上海来,把我和林昭叫去,我们俩都去了。张春元说今天我请客,我们去的是上海绿杨村酒家,在南京西路上。它的扬州菜非常有名,有高价售出的小笼包子。张春元请客,为什么呢?他是正式地告诉我们,他和谭蝉雪结婚了。我感觉林昭对张春元是很倾慕的,张春元请我们吃饭,也是正式地讲明他和谭蝉雪的关系。吃完饭以后,我们一起到当时的碧柳湖公园划船。那天,林昭也喝了酒,他们喝的是白酒,林昭喝醉了。我不会喝酒,没有陪他们喝。

我还记得,1960年初,张春元在去广西接谭蝉雪回河南之前,他突然来到上海。他说,他要做结扎手术,已经有了两个侄儿,不想要孩子了,不要给谭蝉雪添麻烦。他真的去做了这个手术,在上海的中山医院。这个人就是这样的,他做好了破釜沉舟的准备。

那时候,我也有些灰心,张春元把心思都放在谭蝉雪偷渡那里,林昭对《星火》也保持着距离。我感到,她跟我想象的那个人不一样。张春元曾经说过开一次会,大家来定下组织纲领。因为我在上海,和林昭联系方便,便让我联系林昭。题目都定好了,请林昭写反右对知识分子的政策,我写《论寡头政治》,分析政治体制问题。我跟他们说,不要找林昭了,她不想弄这个事情。在我的印象中,林昭的兴趣都在文学方面。既然她不回应我,我也不跟她谈政治了。

三、别梦苏州

林昭在上海时,一般都是她给我来信,约我到公园去见面,大概一两个礼拜她来一封信。记得有一次见面,她说新蚕豆刚上市,她母亲托我在黑桥乡下买上几斤。我与乡下的邻居从不来往,不知道该去哪里买。她见我无回音,在下一次见面时就说,已经托别人买到了。我知道她对此很不高兴,但我心里想,她迟早会知道我是什么样的人。

我给她的《星火》,她藏在一个抽屉的厢肚里。老式的抽屉,抽出来以后,里面还有一点空间,只有把抽屉全部抽出来,才能看见藏在最里边的东西。那一年的端午节前夕,她们家大扫除,她母亲发现了藏在里面的《星火》。林昭和我一样,划右派后的处分是劳动考察,因身体不好被母亲从北京接回上海。她母亲得知我们这种思想倾向,马上禁止她再和我来往。

在此之前林昭还跟我讲,她母亲对我印象不错。发现《星火》后就改变了态度,母亲不许她继续留在上海,她要林昭去苏州居住。林昭去苏州前,约我在襄阳公园见面,与我告别。她还转述了母亲对《星火》的评价,大意是说,《星火》“是一些不懂事的年轻人对当局发泄不满之举”。她给了我她在苏州的地址,我一看,上面写着:苏州乔司空巷十五号许萍。我不知许萍是谁,她说是她自己。这应该是化名,用了她母亲的姓。但林昭去苏州后,不仅没有与我断绝往来,而且来信更多,写得更长了。她就是那样的性格,你不让交往我偏要交往。她一个礼拜来两三封信,我一封回信还没有寄出,她的下一封信就到了。她约我到苏州去,她也从苏州到上海来看我。

1960年5月底,林昭回苏州,到10月份我被捕,我们密集通信和见面就是在这段时间。在上海的时候,林昭的来信不到两行字,主要是写在什么地方、什么时间碰头。到了苏州就完全不一样了,每封信长得不得了,一写五、六张纸,这位老兄实在笔头会写。

她也从苏州到上海来,那一次我们真正是像男女朋友date(约会的意思,编者注)一样。她一早做了好多点心,带了菜,约我到火车站去接她。接了她以后,我们到虹口公园,吃好饭,我再送她回苏州。

我到苏州去过三四次,林昭趁母亲不在家的时候就约我去。我们先在观前街一个庙前见面,然后她说要回家去换衣服,记得是到虎丘还是什么地方去玩,要乘长途车。她领我到了她家,叫我在院子里等,她进去换衣服。这是一个独立的院子,我没有看到其他人,所以也不知是她们一家人住还是与别人合住。

我随她在苏州那些巷子到处转,苏州那些私家花园很多,她熟得很。路上碰到人,一会儿跟这个打招呼,一会儿跟那个打招呼。吃饭、看戏,到哪里去,反正听她指挥。

在苏州逛街,我看到有人在地摊上卖旧书。我过去看,有不少外文书。其中有一本是法文原版的数学名著,好多数学书里都引用过它。那些书的主人去了哪里呢?也许跟我们的命运一样吧。我喜欢这些书,林昭还帮我与摆书摊的人还价,但那时候我没有钱,也买不了。在兰大读研究生时,每月还有六十块钱,反右以后就取消了。从天水逃回上海,生活上还需要父母接济,口袋里就是哥哥妹妹给的十块钱。苏州虽然离上海很近,车票也要四五块钱,我去后还要住旅馆,都需要花费。

那年我25岁,从没有交过女朋友。林昭是28岁,伶牙俐齿的,道理都在她嘴里。反正,她想对你好的时候,也是很好,很可爱的。后来她的信也写得越来越大胆了,我意识到一种可能性。但在上海时,我请她去我家,她也不去。所以我也不是很确定,她心里对我到底是怎么想的。

我们在一起的时候,百分之九十九,都是她在讲话,我只是听。关于政治笑话、小道消息,还有北大的事情,她知道的多得很。

有一次她跟我讲到她的父亲,她父亲,是在劳改还是劳教吧?她说,她不久前去看她父亲,坐了船。不知是不是在白茅岭农场。

【林昭的父亲彭国彦1955年9月被捕,初判徒刑7年,他不服上诉。1956年苏州市中级人民法院判决:“其历史身份已在反动党团登记时基本交代,偷听‘美国之音’是非法的,但念其在解放后不久,又未大肆传播,此外无其他罪行足以惩罚,撤销原判,教育释放”。1957年反右运动后以“历史反革命”罪被判管制5年。因与许宪民离婚,长期无工作,以典贷、跟人做佛事过日,被安排到一街道小厂做敲工,月发16元。】

1960年6月2日,谭蝉雪在偷渡途中被抓。偷渡之前谭蝉雪来我家时,我介绍她认识了我的北大同学梁炎武,也说好了,她在广州时,如有需要,可以联系梁炎武。谭蝉雪在看守所被关押期间,她真的给梁炎武写了信。梁炎武接信后,设法通知了张春元。因为传递了信息,梁炎武被牵连进我们这个案子。

梁炎武和我在北大同学四年,人品正直,我们关系很好。毕业后他留在北大任教,结果也打成右派,送到工厂劳动考察。1960年4月,他辞职回到广州的家中。

梁炎武的父亲是广州中山医学院的著名教授,他的几个姐姐都是医学院毕业的,只有他学了物理。

张春元得到梁炎武的信后,立即去开平,准备营救谭蝉雪。以前他都是先到上海,但这次他没有先来与我商量,直接过去了。他用了假身份,被看出破绽。7月15日,张春元也被捕了。

我是从梁炎武那里知道张春元被抓的,那时梁炎武的一个姐姐刚好要从广州回到上海,梁知道事情严重,立即托她带信给我告知此事。信由他姐姐带到上海,他写信给我,让我到她姐姐家里去。我去后,他姐姐把梁炎武的那封信给我,里面就讲,谭蝉雪已经出事,张春元也被抓起来了。

张春元被捕,他是怎么通知了梁炎武呢?这个我就不清楚了。也许他和张春元在广州见过面,他们之前是否有约定,后来我没有细问。

总之,得知张春元被捕了,我感到情况不妙,想到的第一件事就是告诉林昭。我没有苗庆久的地址,跟苗庆久从来不联系的,所以我没法告诉苗庆久。

我直接去了苏州,到苏州时我觉得,背后可能已有人在监视。

在苏州一见到林昭,我就跟她讲:今后我们不要来往了。你把我的信全部烧掉,因为我要一出事情,我们之间写了那么多信,肯定要受连累。

她一听就火得很,好像我无缘无故要跟她分手。她也不跟我说怎么办,她似乎不相信事态会发展到如此严重的程度,远在广东开平的偷渡案,怎么会影响到她和我。她心里可能想的是:你说不来往就不来往啊!

临走时,我要她不要送我。她在我的背包里,塞了一份东西,我也不知道什么东西。上火车了,打开一看,是她最近写的一篇文学评论,关于白居易的《琵琶行》。我知道她的意思呀,什么分手啊,不要轻易放弃。

这就是我们最后一别,我都没有机会和她说清楚,并不是我真的要和她分手。我也不知道,她到底烧掉我的信没有。

四、信义

我在乡下住的老房子很大,比我们现在住的房子高多了。每一间房都有隔板(天花板),隔板中有一块是可以打开的,把这个板抬起来,上面就像阁楼一样,有很大的空间,而且很暗。我在阁楼里藏了很多东西,有油印机、印好了的张春元文稿、林昭的全部来信……所有要紧的东西,我都藏在里面了。

这些事情,还有我对被抓捕的预感,我一点也没有告诉过家里。

从苏州回来以后,我还在翻译法文小说。那段时间,译完了梅里美一个短篇《马铁奥·法尔哥尼》,其中讲的是科西嘉岛上一家人的故事。这家人中的父亲在当地声誉很好,还是一个神枪手。他有一个独生子,大概十来岁。一个逃犯为躲避追捕,拿出5个法郎给这个小孩,自己藏到了他家的干草堆里。而官兵随即赶来,要求小孩指认逃犯的去处。小孩开始时拒绝了,可是,当官长拿出一只银质挂表时,他终于忍不住了。为了得到挂表,他指出了逃犯的藏身之处。这时,他的父亲回来,被捕者对着马铁奥的家门唾骂道:“奸贼的家!”

他的父亲背上枪,叫小孩跟他走,走到山里,只听见砰的一枪,他把自己的儿子处决了。

你可能会觉得这样的父亲很没人性,但这里突出了一个信义的主题,有人就是把信义看得比生命更重要的。

1960年10月,我刚好翻完这篇,准备拿给傅雷看的。我推测现在这篇译稿应该还在我的案卷中。

苏州别过,林昭不再来信了。她的信没法寄到我在乡下黑桥的住处,这里邮差可以来,但是地址很复杂,老房子没有门牌号码。所以我和林昭约定,若是来信,寄到我在西康路的家里。

所有来信,我都是到西康路家中去取的。妈妈知道,我妹妹也知道;她们看到苏州一封信寄来,不久又一封信寄来,信都放在底楼厨房的灶台上,信封写着我的名字,字迹很秀丽,她们就问我是谁。

我说是林昭,北大的一个同学,中文系的,人在苏州。所以她们都知道林昭,知道我们在通信。

我从黑桥可以寄信,但要回去收信。那时也没有电话,只有回到上海,才知道她是不是来信了。我经常回去,从黑桥到西康路。至少每周一次,甚至更多。如果想看看林昭来信没有,我就回去了。那时只有信件交流这一个方式。

所以家里人知道得很清楚,经常来信的人就是林昭。张春元来信也是寄到上海家里的。那天来黑桥抓我的同时,警方也派人去了西康路的家中搜查。公安人员还问了三楼住在阁楼的一个邻居,他是一个单身老头,我不清楚他的情况,平时见面也是很客气的。但警方搜查时问邻居,顾雁平时有什么异常表现?他跟警方汇报,说我在三楼的晒台上烧过一次信。

确实,我接到梁炎武的信就烧掉了。张春元的信、其他人的信、我在上海收到的所有同学的信,全部烧掉了。只有林昭的信,我下不了手。她写信很用脑筋,信封信纸,都很讲究。就是这样一个人,她把写信当作工作来做的,非常认真。所以我就觉得她有那个意思,我原来给她写信称兄的,后来就改称姐。结果她又发火了,好像我在瞎想。我也火得很,她又像什么都没有发生一样。有一次在苏州,我们走到一处院子,她跟我说,这个院子清静,很好。如果能在这里买一处房子过晚年,也是挺好的。

那个老头所住的三楼阁楼,对面是个晒台,在亭子间上面。我烧东西就在那个晒台上,他讲我烧东西,所以静安分局知道了。

审讯的时候他们就问:“你烧的是什么东西?”

你问有什么用处啊?我烧也烧掉了!我讲什么就是什么,这硬碰硬的事情。我是烧掉了,但是烧了哪些?你要问我怎么问得出来?不可能的事情。他也知道我在瞎讲,只能问问就算了。

我把所有其他的信都烧了,不要连累别人呀!就是林昭的信我不舍得烧,我跟她讲我烧掉了,其实全部留下了。张春元、梁炎武、徐诚的信......全都没有留,我给张春元的信,他也一封都不留。就是林昭的信,我全部都藏在阁楼上。至于她烧了我的信没有,我也不知道,很可能也没有烧;因为她是不相信会发生意外的。

所以,审讯的人清清楚楚,她和我的交往,我们之间上海至苏州的来去时间,哪一天发生了什么样的事情,到什么地方会面。你跟顾雁在干什么,信里都写了。所以,审讯的人从来不问,我跟林昭到底有什么交往。

如果不抄我的家,也不会跟她扯上关系。结果,把我的家一抄,她的信就全部被抄走了。何况,《星火》里又有她的诗。这就把她卷到案子里来了。

单从这些信来讲,我想,林昭的信应该是帮了她的。办案人肯定要问她,什么时候跟顾雁来往?这些情况通信里都有,我去了几次,她来了几次......信中完全没有写政治上的事情。我们策划的那些行动,跟她根本不搭界的。她跟武山的人和事也不搭界,谭蝉雪和她碰过一次面,其他的人她都不认识。

五、“抓坏人”

他们不是马上抓我的,至少已经跟踪了我半个月。估计我到苏州去,他们就已经知道了。我有时要从黑桥去周浦镇,买点肉或者生活用品,回头一看,后边好像有个人跟着。我在路上,碰到一个远房亲戚,他还跟我打招呼。后来这个亲戚也被调查了,问他到底跟我讲了些什么。

对,我跟林昭打好招呼了,我的东西都藏好了,我也做好了被抓的思想准备。我知道他们要来抓了,不可能逃啊,往哪儿逃?

我还是一个人住在乡下,我家在一座院子的西边,东边是我叔叔他们家,但他们人都不在,房子是空的。突然一个亲戚来跟我说,队里要租一间房子,公社大队里下来的人。我说这房子不是我的,是我叔父的。

后来那边就搬进来一个租客,是个北方人,因为农村人的口音一听就听得出来。我心里就有点怀疑了,我也知道自己是逃不掉的,人家早就在我对面租了房子,就在一个院子里,每天监视我的一举一动。

1960年10月18日早晨,大概8点左右,我已经吃过早饭。大队书记先来,他一看我在家,跟着就又进来四五个人。来人马上把我反绑起来,铐子也铐上了。我对他们说:“我就是一个学生,你们这样,算什么呢?”而我心里明白,这个结局终于来了。

有个人算不错的,他从墙上拿下我的一件皮的大衣说:“披上!”

10月下旬,天气已经有点冷了。我的手是反铐的,无法穿衣,他把那件皮外套披在我身上。我离开了位于瓦屑镇黑桥我的家,还要走一段路到名为六灶港的河边,那里有机器船开往周浦镇。每天只有一班,9点钟上船,上船后就只有两个人留下来押送我了,其他几个人没上船,他们回去搜查我的住处。

我在黑桥家里还养着鸭子、鸡什么的,都在门外。我还种了好多菜,种了南瓜。

船到周浦镇要上岸,上岸后还要走一段路才到长途公共汽车站。时间接近中午,经过镇里小街时,我披着衣服,手反绑着,后边跟了一大群小孩,他们都在喊:“抓坏人!抓坏人!”

长途车发车也不定时,上车前,押送我的可能先跟司机讲好了,让我第一个上车。上去以后,我到最后一排的位置上坐好,这两个人坐在我边上,车上至少还有二三十个乘客。

从周浦到上海要过江,那时候没有隧道,也没有桥。长途车先开到黄浦江边的周家渡,其他乘客统统下去了,这两个人也不急着下车。我看到有一部吉普车停在那边,他们打个招呼,吉普车开过来。我下了公交,上了吉普车,那两个人也上来了。我还听见他们在车上说说笑笑,因为那时全国的饥荒已波及上海,所以交谈的主题是今天晚饭吃什么。他们问司机,司机也有两个人。

吉普车再渡江,至少要一刻钟。车到了江对面,就直接开到静安分局门口。到达时天色已晚,他们把我押进了审讯室,那里他们早就准备好了,让我坐在小凳子上。

印象中进去以后,可能把我的手铐打开了。一个审讯员坐在我对面,两个大汉站在两旁,审讯大概都是这样。审讯员看上去很年轻,大概从学校刚刚毕业不久,文质彬彬的。

他们怎么问我,那么我就怎么回答,我知道会是这么回事。

从早晨抓了我,一路押送过来,我中饭没有吃,晚饭也没有吃。在审讯室里了审了一个晚上,他们有夜宵的,我说我肚子饿了,后来给了我一个馒头。我说我要水喝,有人倒水给我喝了。

审我的人换班,我就一直坐在里边,连续地受审。他们脸板起来的,我早就准备好了吧,肯定是这副样子。我想好了,你们怎么审,我就怎么答。

问了哪些问题,现在也记不得了。反正我一点都不慌的,开了饭店还怕大肚子来吃饭啊,对不对?早就预料到了,你们要判几年就判几年。

我基本上都是照实讲的,既然我来了,我干了嘛,我承认。但我没有讲发起《星火》的过程,没有讲要寄发《论人民公社》给几省市党政领导人,这些事情当然不讲了。他们问我别的,我就回答吧。

大概在晚上八九点钟以后,突然一个人进来,他跟审讯的人一说,他们马上高兴得不得了。我明白了,肯定是我藏的东西都被搜出来了。我家里有个很长很大的梯子靠在墙边,估计他们一看起疑了:怎么这里还有个梯子的?

六、我听见林昭进来的

林昭跟我一样,先被关到静安分局的看守所,在我被抓的六天之后。我知道她也进来了,女犯进出都要走过我们被关押的监房,因为女监在走道的最里边。

静安分局的原址是解放前有钱人家的一栋花园别墅,一般只有两到三层,但别墅都有地下室,看守所的监房就设在地下室里。

【由上海市公安局静安分局使用的南京西路1550号住宅,原为已故旧上海房地产巨商程谨轩的遗产。该花园住宅占地8500平方米,门前坐有两只石狮子,分列左右两旁。园中建造了一幢八角型式的庭院,高三层楼,中间有大理石的阔型楼梯,庭院后面又建有四层十六间楼房,其中二、三层与庭院相通。】

我们进来时是从地面往下走,楼梯下来先进一道大铁门,眼前是一个走道。走道一边是一排监房,有铁栅门关着。房间一大半在地下,里面没有窗。在与铁栅门相对的那堵墙上边和天花板之间有一条透气窗,里面钉着铁条。从铁条的空档里望出去就是外边的路面。我一看就知道,我们是在地下室里了,就那么一条很窄的透气窗,室内一天到晚都开着灯。

这个看守所到底有多少间监房,我不清楚,他们也不会让你看。我被押进一个房间,铁门啪的关上。我脚伸进去,里面都是人。大概有二三十个人,我就在马桶边上坐下了。

此时已经是10月19日的早晨,监房里的人都端端正正地坐着。

晚上睡觉,监舍里有地板,睡觉都是地铺。别的犯人有被子,我没有。不过几十个人挤在一个小间里,倒也不觉得冷。隔了两三天后,他们通知了我父母,家人把被子送进来了。

那些犯人,各式各样的人,进进出出,一下子这个人放掉了,然后又进来新的人,监房里乱得很。

几天以后,林昭来了。他们提审时要叫名字的,我听见外面有人喊:林昭!接着听见有脚步声从我们监房的门口走过。在静安分局的看守所关了两个月,那确实苦,白天基本上动也不能动。很小的房间,最多的时候关了四五十个人。隔几个小时可以放风一次,其实也就是排好队,在监房里哗啦哗啦走一圈。以后我就知道了,上海市的看守所,有市所与区所之分。后者属区公安分局管辖,规模小,只收容临时在押人员,而流动性大。我和林昭第一次被关进去的静安分局看守所,就属于区所。后来“文革”期间,我妹妹被关进虹口分局看守所,它也是区所。

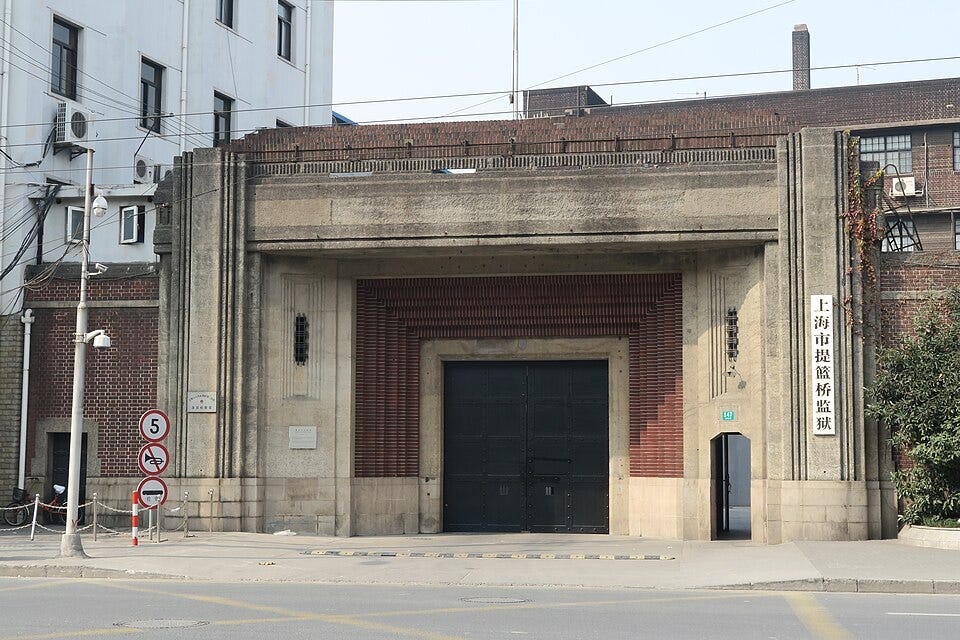

林昭和我不久被关进上海市的第二看守所,林昭再次入狱则被关进上海市第一看守所,这两个所都属于属市公安局管辖。市所的规模大,可收容长期在押人员。其中,第一看守所在南市,三十年代就有了,是租界外中国地带的看守所。第二看守所在思南路,是法租界的看守所(俗称“法国监狱”)。

我在静安分局看守所,被关了大概两个多月,1960年底,我被转到思南路的第二看守所。后来我知道,林昭第一次被捕后的轨迹与我相同。现在来看,这意味着我们的案件被认为案情重大,短时间里不可能释放。事实上,从起诉到判决都五年。虽然我、林昭和梁炎武,我们三个北大校友的名字在同一张起诉书上,但无论是转运期间,还是开庭判决,我和林昭都没有再见过面。而在静安分局看守所时,我也没有见到梁炎武,只是到二所后,一次在放风时我见到梁炎武,那时才知道,他也被抓来上海了。

七、在第二看守所

转到思南路的法国监牢,即第二看守所,那里的条件就好多了,比后来在提篮桥的条件都好。二所的楼层都是通风透气的,有很大的玻璃窗。每个房间里住的人也不多,挤的时候四个人,稍微空点的时候三个人,一般是两个人,但不会让一个人一间。四个人一睡下就肩碰肩了,房间很小,其长度在四人躺下后刚好放一个马桶。早上起来,每个人都要按标准叠好被子(即做内务),白天被子不能打开。管理严格的时候也不让你用被子垫着坐,我们一天天长时间地坐在地上,非常辛苦。地上太硬,我拿几件衣服打成一个包当垫子坐。看守走过来看到就吼:喂!垫子拿掉!

四个犯人,就一直坐在地铺边上。一看有人过来了,也互相告知是谁来了。我们给他们几个主管起了外号,一个叫巡洋舰,一个主力舰,还有一个外号叫“活动政府”,因为那时他们训话,口口声声都是是“人民政府”。

有时候,看守沿着铁栅门偷偷地过来,窥视我们在干什么。一般情形下,他们走对面的那条走廊。这整栋楼的结构跟船舱差不多,中间是房子,外边有个套子,沿套墙一圈也有走廊,它与监房外的走廊之间是铁丝网,两个走廊间用木板的通道相连接,所以从四楼走廊上可以直接看到底楼。晚上看守大多都是从对面通道走,因为安全一点。你想,万一沿着我们这边走,里边的人手伸出来扒一下......大概是这个考虑。

从我们囚室对面的窗户望出去,可以看到广慈医院。它是上海最早的传染病医院,那边有很大的青草地,可以看到里边也有人接见,在一个小亭子里,病人的家属送东西进来。

我想到我的父亲母亲、哥哥妹妹,他们都不知道我为什么被抓进来,我也无法告诉他们。父母肯定忧心如焚,哥哥妹妹,必然也会受到我的连累。每念及此,内心隐痛,但也无可奈何。

不知什么原因,二所的犯人经常被调换房间。从三楼换到四楼,四楼换到五楼,我就这样待了四年多。进去不久后得到一个好消息,可以写送物单了,也就是说,可以让家人送东西进来,每个月一次。这个做法叫“接济”,但不能和家人见面,就像广慈医院的传染病人一样。家里人把东西交给管理员,管理员再交给我。林昭在二所的环境,应该与我是一样的。

八、林昭写了《思想历程》

隔了半个世纪,我才从谭蝉雪找到的案卷资料中,了解到林昭第一次被捕后的思想经历。林昭是1960年10月24日被捕,转到二所后,关到1962年3月5日保外就医。

1961年10月14日,她写了一篇《个人思想历程的回顾与检查》(以下简称《思想历程》)。谭蝉雪在复印件的第一页上注明了,这份资料来自《甘肃省天水市公安局执行股预审卷宗》张春元卷。

这种思想总结之类的东西,当然都要写的,我也写过。在静安分局的看守所里没怎么写,它那边就是要你坦白交代,给你一张纸,交代了以后按手印,走个简单的程序,不会叫你写长篇大论。监房里没有桌子,也没有床铺,白天坐在地上,晚上睡在地上,各人用自己的被子,一半垫一半盖。

转到二所后,这里是地板,但也没有桌子。长篇交代都是在二所写的,因为关押的时间太长,交代来交代去也就是那么多事。交代完了,就叫你写认识,他给你笔和纸。有可能还是把我叫到办公室里去,到外边的桌子上写。

从林昭这份《思想历程》的内容来看,我相信它的真实性,确实是林昭写的。但在复印件上再度复印的纸件相当模糊,我只能根据谭蝉雪后来编辑到《林昭文集》里的文本来看林昭的观点。在复印件和整理稿中,我看到大量使用了省略号,这让我想到,会不会是办案人员从上海抄来,自己加的省略号?因为犯人写交代是不可能用省略号的。因为没有看到原件,这个问题留给你们去研究。此外,我还认为,办案人员来上海,主要是要了解我的交代。林昭的这份《思想历程》,他们只是附带抄一下而已。林昭的这份检查,可以证明前面我的观点:林昭与《星火》案,与我们这群人,在思想上有很多共鸣;我和张春元,都是她很重要的朋友。但她对于我们想要采取的行动,一方面是了解有限,另一方面也的确不想介入。如我上面所说,是若即若离的。简单地说,根本就不应该抓她,她跟这个《星火》案没有太多关系。如果我要反省的话,甚至可以说,是我害了她。如果我没有刻印《海鸥》,如果我没有和她走得那么近,如果我没有保留她给我的三十多封信,很可能,她不至于因为《星火》案被抓。

在这篇检查中有几处提到我的名字:

第一次提到我,她说,她通过我,了解了北大和兰大反右以来的一般情况,有了共同的思想基础:

“顾雁他们本来早已邀我上西北玩儿一回去,我苦于没法脱身,也怕引起注意。以后他也身体不佳回南了,这便很巧。通过接触,很快沟通了、交流了北大与兰大反右以来的一般情况。”

但是谈到这一点后,她认为,应该“独立存在、独立作战”,不斤斤计较什么组织不组织。她说我其实也是明白这一点的,我在前面已经讲过,林昭与我们没有组织联系,这份文字再次证明了这一点。这时她第二次提到我的名字:

“对着顾雁我没很强调这一点,一来因为暂时尚无强调的实际需要,二来,他也是北大出身的,总还有相当强烈的“北大观念”、不烦十分强调。”

第三次提到我的名字是说《海鸥》,可见当时在查抄到我刻印的《海鸥》后,静安分局最初提审林昭,这首诗是关注重点。但林昭对此也不在乎,刻印非她本意,诗原本就是私下里人手相传的。她不介意朋友传阅,但她很明确地表示,没有必要刻印散发。我从这里看到,她对我是很有点火的。由于我的刻印,她的诗从地下写作变成了公开写作,她认为这不是相得益彰而是相反,作者和读者都受其害。她是这么写的:

“在京时我曾手抄以传阅和赠送过,那个,另一回事,那还勉强可以算在合法的范围里,至多你来批判我这诗便是了。一到印刷,虽是油印,亦总有点哗众取宠、惊世骇俗。一副像煞有介事之态,其实又没啥了不起,‘鞋子不着落个样,月亮里点灯空挂名’,我不为也。否则,当年还曾参与地下党的散发、翻印宣传品等活动。我又不是没有半套,就说印东西,除了一听油墨少不得外,其他什么不用,使图钉把刻好的蜡纸往桌面上一钉,不照样印出来?有何难哉!不过没有着手进行耳。”

我看她这段话里有几层意思,主要就是为自己辩护。也就是说,第一,她不知情。第二,若是知道,她也不会同意。她用了很不以为然的语气来贬低我们刻印《海鸥》的意义,把我们的行为说得好像是很没有意思的事情,一副“哗众取宠”“煞有介事之态”。总之就是:这有什么了不起呢?这种事情我以前早就搞过的,比你们还要高明得多呢,不过是我不做罢了。

她为什么不做呢?她接下来就说,因为印秘密宣传品,印的人是冒险,读的人同样是冒险。还有就是,你到底有什么新东西给别人看呢?如果是些尽人皆知的道理,也并不值得去印。

我看到这些地方,我就想到,当年我们准备将张春元的《论人民公社》刻印出来,传递到高层干部手里。这在林昭看来,似乎就是老生常谈,根本没有什么价值。而且我们还误解她了,以为她是怕,但她并不是怕——我不参与,是因为不值得,“不值得便不干”。她就是这么写的:“可我这种主张曾受到误解,使得我相当生气——已经走到了这么一步,难不成我还惜此一身么?”

那么,林昭的这些话,到底是她的心里话,还是为了减罪而避重就轻呢?

我觉得,这两种成分都存在。既然是根据办案方的要求来写,而且是写检查,在认识上写些符合大形势的套话,都是可以理解的。但林昭对我们行为的否定,我看了以后是不认同的。

此外,从这份检查里,还可以看出一个逻辑,那就是林昭保外就医离开二所后,为什么又会再次入狱。

那么关键在哪里呢?我觉得是林昭对形势判断错了。不仅是她,我当时也有误判。还有就是,我有一个现实的考虑,我要活着出来。而林昭为了理想,她是不顾一切的。这和她的思想、经历和个性有关系。在这些方面,我和她是有差异的。

如今来回想我的青年时代,对照林昭的思想历程,对这种差异能看得更明显。当我们俩在一起时,处在那种朦胧的情感状态,我前面说过,彼此很少谈那些政治话题。你想想,我将《星火》送给她时,里面那么多抨击时弊的文章,她当然了解我们的思想倾向。我写的《发刊词》,她还不明白我对现实的态度吗?这都是心照不宣的,不用重复。我们在一起,讲的都是些日常生活的话题。

现在来看,我们卷入政治的程度,也是不一样的。

从家庭来说,我的父母都属无党派;虽然我的姨父姨母也是共产党的资深干部,但我们受父亲影响是主要的,对执政党、政党政治,保持了一定的距离。我跟你讲过嘛,斯大林死的时候,要我们戴黑袖套,我们就不肯戴。而林昭那时写了《斯大林鼓舞我们永远前进》一诗,里面有这样的句子“哪怕是失去了自己的父母/也不会比今天更使我们痛心!”林昭的家庭政治色彩比较浓,她自己在中学时代就参加过共产党的地下工作,她的老同学证明她在中学里加入了共产党。在《思想历程》里,她也表明,她是“未解放前就积极参与地下党所领导之学生运动、且曾一度有组织关系的人”。后来据说是因为她没有服从命令撤离苏州,失去了党籍。她在《思想历程》里表白说:

“但我既然曾在红色恐怖的年代里追随了党,以青少年的纯真热情呈献给党,则从个人本位出发来说,对于党的一切作为:美政或暴政,在政治上都应义不容辞地担负全部责任。”

而我从中学时代就希望投身物理研究,我对政治不感兴趣,更不想搞政治。1980年2月,我和梁炎武都在上海,等待案件复查,9日,我们一起去苏州,参加为林昭母亲召开的追悼会。在车上,我第一次遇到倪竞雄,她知道我是林昭的同案就问我:“你搞物理学的,怎么也来搞政治?”我说:“不是我要搞政治,而是政治来搞我啊。”

还有,林昭也有一定的城府,不是我在初读《海鸥》时所想象的那样,是一个单纯的诗人。她比我的社会经验丰富,有更多的阅历。她参加过土改,在报社工作将近两年。我则是从学校到学校,从本科到研究生。如果不是到天水劳动考察,社会经验就更有限。她对政治的很多思考,我还没有机会深入了解。

为什么被捕前,我们曾经走得那么近,一度感觉像男女朋友一样呢?应该是我们共有北大情怀,又都因为反右遭到重创,心意彼此相通。我们同样被断送了专业前程,都是在混乱中回到上海。我们命运未卜,思想上离经叛道,欣赏彼此的才智。只不过,这种倾慕的情愫正在萌生,就被这场政治围捕阻断了。

到我们被抓进去后,我完全没有想到,林昭后来会遭到那么惨烈的虐待,以至于牺牲生命。我是一进去就准备好了,我不抱什么希望,随便你们判几年;反正已经在你们手里了,你们说怎么办就怎么办。不管你用什么办法,我就守住我的一套。我的想法是承受一切考验,我要活着出去。

但是林昭后来的变化,和她在《思想历程》里写的就完全不一样了。我觉得她没有预料到,我那时也不可能知道,狱方会把她放出去。而且,放她还另有目的,那就是要找到“大哥”。林昭觉得自己是清醒和自觉的,她哪能知道背后的罗织和拿她做钓饵的预谋呢?她是真诚地相信党的路线已经改变,已经在革新了,这是她在《思想历程》里写到的。

我无法确认,她写这个思想检查时,是不是已经得到了某种暗示或者保外就医的承诺,就是说很快会放她出去。也许有这样一种可能,她以为写了检查,这个案子就过去了,不仅会放她,也会放我们这些人。她明确表了态,拥护党的路线;她以为事情就这样过去了。

但我读了《思想历程》,一个强烈感受是,她不应该把我们做的事情看得毫无价值。你本应该倒过来强调:他们的批判是有意义的,虽然我没有参加,但他们是正义的——你应该这样做的。

而她在文中把我们讲得那样幼稚,做的事情毫无意义。不管怎样,我们是认认真真,冒了风险去做的。林昭却居高临下,把我们讲成那个样子。

你可能会说,林昭贬低我们,也是想为我们开脱,让警方认为,这些人也并没有干什么大不了的事情。我觉得,林昭并不是这样玩世不恭,她的检查里,很多内容、包括她的思想转变,只有她写得出来,不是一般的套话,而是有相当的真实性。我能感觉到,她对我也是很火的:你们搞这些根本不像样的东西,把我拖了进来。

(未完待续)

“She Chose a Martyr’s Path”: Lin Zhao and Me (Part 1) (Selected Excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoirs)

Narrated & revised by Gu Yan

Written & compiled by Ai Xiaoming

Editor’s Note:

Professor Gu Yan, a founder of the influential underground journal Spark during the Great Famine, celebrated his 90th birthday on August 23, 2025. In 1960, he was arrested in Shanghai for his involvement in the Spark case along with the poet Lin Zhao and a friend, Liang Yanwu. Gu Yan was sentenced to 17 years in prison in 1965 and served his time in Qinghai. After his rehabilitation in 1980, Gu Yan began teaching at Lanzhou University as a theoretical physicist. He retired in 2001 and now lives in Hefei.

Although they both attended Peking University, Gu Yan was a physics student and did not know Lin Zhao, who was three years his senior and a journalism student in the Chinese department. Before secretly launching Spark in the northwestern city of Tianshui in 1959, Gu Yan personally inscribed Lin Zhao’s long poem “The Seagull” onto a mimeograph stencil, printed it, and shared it with friends. He also published another of her poems in the first issue of Spark. In 1960, while visiting family in Shanghai, he met Lin Zhao. Over the next three to four months, they corresponded frequently, developing a deep affection for each other and exchanging dozens of letters. Gu Yan and Lin Zhao were subsequently arrested. Lin Zhao was later released on bail but, after being re-imprisoned, she was tortured and executed on April 29, 1968.

This article, presented in two parts, is an excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoir, compiled by Professor Ai Xiaoming. Here, Gu Yan offers a detailed, first-person account of his relationship with Lin Zhao and her connection to Spark. For the first time in 66 years, Gu Yan, one of the journal’s founders, provides a comprehensive look back at his life and the events of the Spark case. His deep affection for Lin Zhao and the “grief and shame” he felt upon hearing of her sacrifice while he was still in prison are profoundly moving. As a direct participant and witness, Gu Yan’s memoir holds immense historical value.

The China Unofficial Archives is honored to be the first to publish this work, which sheds light on the creation of one of the most important underground magazines in the history of the People’s Republic and commemorates Lin Zhao, an important intellectual who gave her life in her fight against tyranny.

The Chinese title of this article (“She walked the path of Xia Yu”) refers to a revolutionary character from a Lu Xun short story, based on the real-life revolutionary and martyr Qiu Jin. After Lin Zhao’s execution, the grief-stricken Gu Yan, who was still serving his sentence in Qinghai, was unable to express his feelings openly in letters to his family due to strict censorship. Instead, he could only hint at the tragedy by saying that Lin Zhao “walked the path of Xia Yu.”

Foreword

This past April 29 marked the fifty-seventh anniversary of Lin Zhao’s death. Twenty-six years ago, Lin Zhao’s close friend Ni Jingxiong asked me to write an article in her memory, but I never finished it. Over the years, I’ve been interviewed by Hu Jie, Fu Guoyong, Wu Mingwei, and Jiang Xue, and I’ve responded to letters from Hu Jie, Yi Wa, and Tan Chanxue about Lin Zhao. The topic has always been the same: my relationship with the Spark journal and with Lin Zhao.

Lin Zhao and I parted ways in the autumn of 1960. Later, as co-defendants in the Spark case, we were indicted and sentenced at the same time. I survived, but Lin Zhao became a martyr, and so did our friend Zhang Chunyuan, who co-founded Spark with me. We were in our twenties when we met. Now in my twilight years, writing down these memories is both the responsibility of a survivor and my long-held wish.

My acquaintance with Lin Zhao began with her poem, “The Seagull: Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death.” Our cases were related to Spark, and our fates were once intertwined.

My eldest brother Gu Hong and my younger sister Gu Mi were also implicated because of my relationship with Lin Zhao, and they were nearly killed during the Cultural Revolution.

Many who study Lin Zhao and the Spark case consider her one of the founders of the journal, although this is not accurate. Lin Zhao did share ideological common ground with me and Zhang Chunyuan. My personal friendship with her is even more unforgettable. I haven’t joined in the reminiscences of Lin Zhao by my fellow alumni and peers because I have different views on some matters. My sister Gu Mi, on the other hand, did write a memorial article, which was ghostwritten by my brother-in-law, Li Huikang.

Another thing that moved me was an experience recounted by Peking University alumnus Zhang Yuanxun. On May 6, 1966, Zhang, a classmate of Lin Zhao’s from the Chinese literature department at Peking University, visited her at Tilanqiao Prison. During their meeting, Lin Zhao told him, “I could be killed at any moment. I believe there will come a day when history will speak of today’s suffering! I hope you will tell future generations about the suffering of today! And I hope you will collect and organize my manuscripts and letters into three special collections: a poetry collection titled Ode to Freedom, a prose collection titled Past Life, and a collection of letters titled A Bouquet of Love Letters.”

Lin Zhao wrote at least thirty letters to me. In her short life, she probably wrote more letters to me than to anyone else. To compile A Bouquet of Love Letters, we would need to retrieve the letters that were confiscated from our case files back then. I hope that when the archives of the Jing’an District Court in Shanghai are made public in the future, I will be able to retrieve all the letters between Lin Zhao and me.

1. I Engraved and Printed Lin Zhao’s Poem, “The Seagull”

Before I met Lin Zhao, I first read a draft of her poem, “The Seagull: Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death” (hereafter, “The Seagull”). I recall it being around April or May of 1959, although Zhang Chunyuan’s prison testimony mentions the summer break—July or August—so my memory might be inaccurate.

The poem was passed to us by Sun He, a Shanghai native whose sister, Sun Fu, was Lin Zhao’s classmate. Zhang Chunyuan obtained the poem from Sun He and showed it to me. At the time, I was teaching physics at Tianshui No. 2 Middle School. I was so moved and impressed by the poem’s integrity that I loved it. “Let’s engrave and print this poem,” I suggested. I wanted to print it to share it with a few close friends. I engraved the stencil on a steel plate and printed several copies at the Ma Paoquan tractor station. Zhang Chunyuan was the station master and had his own office, which contained all the mimeograph equipment.

Half a century later, Tan Chanxue found the case file for the Spark case in Tianshui, and the poem was among the documents. When she obtained it, she asked me, “Is the handwriting on ’The Seagull’ in the file Lin Zhao’s?”

“That’s my handwriting,” I replied. She was surprised: “It’s a case file document; how could it be yours?” “It’s a mimeographed copy,” I explained. “The original manuscript was with Zhang Chunyuan.” When I saw the handwriting on the photocopy, I immediately recognized it because it was my typesetting and my engraving.

The author of the postscript for “The Seagull” was signed “Lu Fan.” When Tan Chanxue asked who that was, I told her it was a pseudonym Zhang Chunyuan used. He told me, “Lu Xun has passed away; if you remove the ‘walk’ radical (辶), you get the character ‘fan’ (凡).” Zhang Chunyuan’s writing style in the postscript also imitated Lu Xun’s. When he gave me “The Seagull,” he had already written the postscript.

Zhang Chunyuan appreciated the poem’s spirit—the idea that “one’s head may be severed, but one’s will cannot be bent"—but he also felt that the slogan “Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death” “seemed exaggerated.” He believed one shouldn’t dwell on sadness but should act with collective strength. To protect Lin Zhao and avoid risk, he intentionally dated the postscript to the eve of May 4, 1949, and wrote that “the author is a young student with aspirations in literature and art, who was mistakenly arrested by the authorities during the student movement a couple of years ago and whose whereabouts have since been unknown.” These statements were all intended to divert suspicion.

After I printed “The Seagull,” Zhang Chunyuan distributed copies to our Rightist classmates who were undergoing re-education through labor in Tianshui. I’m not sure exactly who they were. Initially, Lin Zhao’s poem had no direct connection to Spark, as the journal’s founding came later.

[Note by Ai Xiaoming: According to Zhang Chunyuan’s prison testimony: In September 1959, after returning from Xining, Sun He began corresponding with Lin Zhao, who had worked at Renmin University, through his sister Sun Fu’s introduction. He then received the long poem “The Seagull” from Lin Zhao.

From September to October of the same year, at the Dongquan Tractor Station in Tianshui, Zhang Chunyuan and others mimeographed several articles, including “On the Grain Problem,” “Chairman Mao’s Letter to Party Members and Cadres in Rural Areas Nationwide,” “The Seagull,” and “Behind the Scenes of Rehabilitating Cao Cao.”]

Lin Zhao had another poem, “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion,” which I did not engrave. Of the two poems, I read “The Seagull” first.

I started at Peking University two years before Lin Zhao; I was in the entering class of 1952, and she was in the entering class of 1954. Lin Zhao was a transfer student from a work unit with previous work experience, so she was two or three years older than me. I didn’t know her at the time, but I knew she was a well-known figure. I later told her that if I had met her back then, she wouldn’t have even looked at me. Look at the photos of her at Peking University—she looked so proud, like the kind of person who looked down on everyone.

Shortly after I printed “The Seagull,” Zhang Chunyuan had to go to Shanghai on a business trip. He told me he was going to look for Lin Zhao. Zhang Chunyuan got Lin Zhao’s address from Sun He and went directly to No. 11, Lane 159 on Maoming South Road. He brought the mimeographed copies of “The Seagull” and the postscript to Lin Zhao.

They likely had a great conversation and found common ground. Lin Zhao then voluntarily gave Zhang Chunyuan a poem she had recently written. It was written on light blue stationery, with each sheet trimmed to one-eighth of its original size and several pages bound together, small enough to fit into a pocket. This small booklet was exquisitely made, and Lin Zhao’s handwriting was elegant, leaving a deep impression on me.

This long poem was “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion.” Lin Zhao used the Greek myth to express a spirit of self-sacrifice, as if to say, “If I don’t enter hell, who will?” I thought she was telling us that she wasn’t as passive as we might have imagined.

In November 1959, Zhang Chunyuan, Miao Qingjiu, Hu Xiaoyu, and I gathered at a guesthouse in Beidaobu to discuss founding Spark. I suggested we include the Prometheus poem. The original manuscript was likely taken back to Wushan by Miao Qingjiu, who had volunteered to be in charge of engraving and printing Spark.

In December 1959, after we decided to print Spark, our group split up. This wasn’t due to a clear plan of action but was mainly due to practical reasons, with everyone considering their own future. Miao Qingjiu and Hu Xiaoyu stayed in Wushan and Tianshui, respectively, while I returned to Shanghai. Tan Chanxue had already gone back to Guangxi, and Zhang Chunyuan was preparing to return to Henan.

Therefore, it can be said that Lin Zhao was not involved in the planning or founding of Spark. Her connection to the journal was mainly through these two poems. And she didn’t ask us to print them; we decided to do it ourselves. That’s why, after her arrest, Lin Zhao said I “infringed” on her copyright. Indeed, when I engraved “The Seagull,” I had never even met her, so it was impossible to ask for her consent.

[Lin Zhao wrote: “At the police sub-bureau, the case officer asked me about Gu Yan printing ‘The Seagull.’ I told him I didn’t know about it beforehand. I had no choice but to let the matter stand. If I had known earlier, I would have absolutely refused! I have the right to refuse as the original author. ‘The Seagull’ has a certain rebellious sentiment, but it’s nothing more than that—it’s not worth printing; it can’t give much to others.” From “A Review and Examination of My Personal Ideological Journey” (October 14, 1961). Subsequent quotes from Lin Zhao are all from this article she wrote at the Shanghai No. 2 Detention Center.]

The claim that Lin Zhao, Zhang Chunyuan, and I jointly founded Spark is widely circulated but is not true. In 2003, Ni Jingxiong sent me a “Chronology of Lin Zhao,” and when I saw that statement, I wrote a letter to the editor through Ni Jingxiong, requesting a correction. However, my letter was like a stone sinking into the sea, with no reply. I later discovered that in the appendix of the book A Closer Look at Lin Zhao (2007, Ming Pao Publications), the editor still insisted on this claim.

Looking back at this history, it’s clear that Lin Zhao did not directly participate in the specific planning of Spark, but her two poems had a direct influence on the ideological understanding of Zhang Chunyuan and me and contributed to the birth of Spark. At the very least, they made us both realize that there were indeed some young people in China who were willing to make sacrifices to change an unjust reality.

2. “‘The Two Feet’ Is Here to See You”

At the end of 1959, I returned to Shanghai under the pretext of recuperating from an illness. I lived in my family’s old house, “De Xing Tang,” and registered my residency using the pseudonym Gu Yu.

When I was leaving, Zhang Chunyuan told me to use a secret code when I met Lin Zhao. This was a phrase he and Lin Zhao had agreed upon, so she would know it was me. I can’t remember the exact phrase now.

I felt a great deal of respect for Lin Zhao from having read her poems. It was with this feeling that I arrived at her home on the second floor of Lane 159 on Maoming South Road in early January 1960 and knocked on her door.

Lin Zhao opened the door. When she realized who I was, she asked me to wait for her at the nearby Fuxing Park. This was our first meeting. I brought the first issue of Spark, which had just been printed and included her long poem, “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion.” Before I left Tianshui, I had gotten five copies of Spark from Hu Xiaoyu. I gave one to my Peking University classmate, Liang Yanwu—who had also been labeled a Rightist—and another to Lin Zhao. The remaining three copies were later confiscated by the Jing’an police sub-bureau.

A few days later, Lin Zhao wrote to me, asking to meet at Zhongshan Park. This time, she brought a copy of Lü Simian’s A History of Modern Chinese Political Thought. She told me she was reading it and that it was an excellent book, so she lent it to me. That day at the park, she told me some anecdotes about famous people from the Republican era and shared a little about her own life, but she didn’t mention Spark at all. I didn’t dare ask about it directly.

From that day until my arrest on October 18 of that year, we had a relationship for nine months. In Lin Zhao’s home, I had a nickname: “The Two Feet.” Lin Zhao’s mother must have seen me, but Lin Zhao never formally introduced me. Whenever I went to see Lin Zhao, she would come out, and we would go downstairs together. I was taller than Lin Zhao, and her mother, seeing my two feet behind me as we went down the stairs, would ask her: “Did ‘The Two Feet’ come looking for you again?”

During those nine months, Lin Zhao and I met over a dozen times and exchanged dozens of letters. She never mentioned her opinion of Spark. She never asked how I became a Rightist, and I never asked her about the Red Chamber (Honglou) or The Plaza (Guangchang) journals. In our later meetings, she never raised any serious political or theoretical issues. I had mentioned my and Zhang Chunyuan’s planned activities to her many times. I was printing things in the countryside, so I hoped she could offer some ideas or even get involved, but I felt that Lin Zhao intentionally avoided these topics.

Zhang Chunyuan also came to Shanghai to see her directly, hoping she would join our cause. I’m not sure what she said to him, but Zhang Chunyuan told me he could tell that Lin Zhao was reluctant to join our group. I thought this was natural: she knew the two of us, but she didn’t know the large group of people behind us. I clearly realized she wanted to keep a distance from our group’s activities. This undoubtedly disappointed me, but I also completely understood.

Around March 1960, Zhang Chunyuan came to Shanghai and invited Lin Zhao and me to join him for a meal. We went to the Lu Yang Cun Restaurant on Nanjing West Road, a famous restaurant known for its Yangzhou cuisine and expensive steamed buns. Why did Zhang Chunyuan treat us? He wanted to officially tell us that he and Tan Chanxue were married. I felt that Lin Zhao admired Zhang Chunyuan very much, and his treating us to this meal was a way of making his relationship with Tan Chanxue official. After we ate, we went to the former Biliuhu Park to go boating. Lin Zhao drank some liquor that day and became drunk. I don’t drink, so I didn’t join them.

I also remember that in early 1960, before Zhang Chunyuan went to Guangxi to pick up Tan Chanxue and bring her back to Henan, he suddenly came to Shanghai. He said he was going to have a vasectomy because he already had two nephews and didn’t want to have children, so he wouldn’t bother Tan Chanxue. He had the surgery at Zhongshan Hospital in Shanghai. He was that kind of person—he was determined to not look back in his pursuit of ideals.

At that time, I was also a bit discouraged. Zhang Chunyuan was preoccupied with Tan Chanxue’s plan to flee the country, and Lin Zhao was keeping her distance from Spark. I felt that she was different from the person I had imagined. Zhang Chunyuan once suggested we hold a meeting to set the organization’s charter. Since I was in Shanghai and had an easy way to contact her, he asked me to reach out to Lin Zhao. We had even decided on the topics: Lin Zhao would write about the policy toward intellectuals after the Anti-Rightist Movement, and I would write “On Oligarchy,” analyzing the political system. I told them not to bother contacting Lin Zhao anymore; she wasn’t interested in this work. My impression was that Lin Zhao’s interests were primarily literary. Since she didn’t respond to me, I stopped talking about politics with her.

3. Dreamy Farewell in Suzhou

While Lin Zhao was in Shanghai, she usually wrote to me, arranging to meet at a park. She would send a letter about once every two weeks. I remember one time she mentioned that fresh fava beans were in season, and her mother had asked her to get a few pounds from the countryside in Heiqiao. I didn’t have any contact with people in the countryside and didn’t know where to buy them. When I didn’t respond, she told me at our next meeting that she had already asked someone else to get them. I knew she was unhappy about it, but I thought to myself that she would eventually learn what kind of person I was.

She hid the copy of Spark I gave her in the deep compartment of a drawer. Old-style drawers had a small space at the back that was only visible if you pulled the drawer all the way out. On the eve of the Dragon Boat Festival that year, her family was doing a major cleaning, and her mother found the copy of Spark. Lin Zhao and I had both been sentenced to labor re-education after being labeled as Rightists, but her mother had brought her back to Shanghai from Beijing because of her poor health. After her mother discovered our political leanings, she immediately forbade her from seeing me again.

Before that incident, Lin Zhao had told me that her mother had a good impression of me. After finding Spark, her mother changed her attitude and wouldn’t allow her to stay in Shanghai. She wanted Lin Zhao to move to Suzhou. Before leaving for Suzhou, Lin Zhao asked to meet me at Xiangyang Park to say goodbye. She also relayed her mother’s opinion of Spark, which was that it was “an act of venting dissatisfaction with the authorities by some immature young people.” She gave me her address in Suzhou, and I saw that it was written as: 15 Qiaosikong Lane, Suzhou, Xu Ping. I asked her who Xu Ping was, and she said it was her. It was a pseudonym using her mother’s surname. However, after Lin Zhao went to Suzhou, she not only didn’t stop communicating with me but also wrote more frequently and penned longer letters. That was her personality—if you told her not to do something, she would do it even more. She would send two or three letters a week; I would get the next one before I had even mailed my reply to the previous one. She invited me to visit her in Suzhou, and she also came to see me in Shanghai.

From the end of May 1960, when Lin Zhao returned to Suzhou, until my arrest in October, we communicated and met frequently. In Shanghai, Lin Zhao’s letters were usually less than two lines long, mostly just stating a time and place to meet. In Suzhou, it was completely different; every letter was incredibly long, spanning five or six pages. She was indeed an excellent writer.

She also came to Shanghai from Suzhou. On one occasion, we truly acted like a dating couple. She woke up early and made a lot of snacks and dishes, and she asked me to meet her at the train station. After I picked her up, we went to Hongkou Park to eat, and then I saw her off on the train back to Suzhou.

I visited Suzhou three or four times, and Lin Zhao would invite me whenever her mother wasn’t home. We would first meet at a temple on Guanqian Street, and then she would say she needed to go home to change clothes. I remember we were going to Tiger Hill (Huqiu) or some other place and had to take a long-distance bus. She took me to her house and asked me to wait in the courtyard while she went in to change. It was a private courtyard, and I didn’t see anyone else, so I don’t know if it was just her family or if they shared it with others.

I followed her as she walked through the alleys of Suzhou. She knew all the private gardens and was very familiar with the area. She greeted people all along the way. Wherever we went, going out for a meal or seeing a play, I just followed her lead.

While strolling through Suzhou, I saw someone selling old books on a street stall. I went over and saw many foreign language books. One was an original French edition of a famous math book that had been cited in many other math books. Where had the owners of these books gone? Maybe they shared a fate similar to ours. I loved these books, and Lin Zhao even helped me haggle with the bookseller, but I had no money back then. When I was a graduate student at Lanzhou University, I had a monthly stipend of sixty yuan, but that was canceled after the Anti-Rightist Movement. After escaping to Shanghai from Tianshui, I had to rely on my parents for financial support and only had ten yuan given to me by my brother and sister in my pocket. Even though Suzhou was very close to Shanghai, the train ticket cost four or five yuan, and I also had to pay for a hotel, so it was a significant expense.

I was 25 years old at the time and had never had a girlfriend. Lin Zhao was 28, and she was so eloquent; she always had a clever way of putting things. When she wanted to be nice to you, she was very kind and endearing. Her letters also became more and more daring, and I became aware of a certain possibility. But when we were in Shanghai, I invited her to my house, and she wouldn’t come. So I wasn’t really sure what she thought of me.

When we were together, she did 99 percent of the talking, and I just listened. She knew a lot about political jokes, rumors, and what was happening at Peking University.

One time she mentioned her father. He was in a labor camp or a re-education camp. She said she had visited him recently by taking a boat. I wondered if he was at the Baimaoling farm.

[Lin Zhao’s father, Peng Guoyan, was arrested in September 1955 and initially sentenced to seven years in prison. He appealed the sentence. In 1956, the Suzhou Intermediate People’s Court ruled: “His historical identity was mostly disclosed when he registered with the reactionary party and group. Eavesdropping on ’Voice of America’ is illegal, but given that it happened shortly after liberation and that he did not widely disseminate information, and there are no other crimes sufficient to punish him, the original sentence is revoked, and he is to be released for education.” After the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement, he was sentenced to five years of public surveillance for “historical counter-revolutionary” crimes. After divorcing Xu Xianmin, he was unemployed for a long time and made a living by taking out loans and performing Buddhist rituals for people. He was then assigned to a small street factory as a metalworker, earning 16 yuan a month.]

On June 2, 1960, Tan Chanxue was arrested while attempting to flee the country. Before her attempt, when Tan Chanxue came to my house, I introduced her to my Peking University classmate Liang Yanwu and told her she could contact him if she needed help when she was in Guangzhou. While Tan Chanxue was detained, she actually wrote to Liang Yanwu. After receiving the letter, Liang Yanwu managed to inform Zhang Chunyuan. Because he passed on the information, Liang Yanwu was implicated in our case.

Liang Yanwu and I were classmates at Peking University for four years. He was a man of integrity, and we had a good relationship. After graduation, he stayed to teach at Peking University, but he was labeled a Rightist and sent to a factory for labor re-education. In April 1960, he resigned and returned to his home in Guangzhou.

Liang Yanwu’s father was a famous professor at Guangzhou Zhongshan Medical College, and his older sisters all graduated from medical school. He was the only one who studied physics.

After Zhang Chunyuan received the letter from Liang Yanwu, he immediately went to Kaiping to try to rescue Tan Chanxue. He usually came to Shanghai first, but this time he went directly without consulting me. He used a fake identity, but it was discovered. On July 15, Zhang Chunyuan was also arrested.

I learned of Zhang Chunyuan’s arrest from Liang Yanwu. At the time, one of Liang Yanwu’s sisters was returning to Shanghai from Guangzhou. Liang knew the situation was serious and immediately asked her to carry a letter to me informing me of the matter. His sister brought the letter to Shanghai, where he wrote to me and asked me to go to her house. When I went, she gave me Liang Yanwu’s letter, which said that Tan Chanxue had run into trouble and Zhang Chunyuan had also been arrested.

I don’t know how Zhang Chunyuan informed Liang Yanwu of his arrest. Maybe they had met in Guangzhou, or perhaps they had an agreement. I never asked for details later.

In any case, when I found out Zhang Chunyuan was arrested, I knew the situation was bad, and the first thing I thought of was to tell Lin Zhao. I didn’t have Miao Qingjiu’s address and never communicated with him, so I couldn’t tell him.

I went straight to Suzhou, and when I arrived, I felt like someone might have been watching me.

When I saw Lin Zhao in Suzhou, I told her, “Let’s not contact each other anymore. Please burn all my letters, because if something happens to me, you’ll be implicated because we wrote so many letters to each other."

She was furious, as if I wanted to break up with her for no reason. She didn’t tell me what she was going to do about it. She seemed unable to believe that the situation would become so serious, that a smuggling case far away in Kaiping, Guangdong, could affect her and me. She was probably thinking, “You say we shouldn’t be in touch, and that’s it?”

As I was leaving, I told her not to see me off. She stuffed something into my backpack. I didn’t know what it was. When I got on the train, I opened it and saw that it was a literary review she had recently written about Bai Juyi’s poem “The Pipa Song.” I understood her meaning: that we shouldn’t break up or give up so easily.

That was the last time we saw each other. I never had a chance to explain to her that I didn’t really want to cut ties with her. I also never found out if she burned my letters.

4. Trust and Integrity

My old house in the countryside was very large. The ceiling was much taller than the one we live in now. Each room had a ceiling, and one part of the ceiling could be opened. When you lifted the board, there was a large, dark attic space. I hid many things there, including a mimeograph machine, printed manuscripts by Zhang Chunyuan, all of Lin Zhao’s letters... I hid all the important things there.

I never told my family about any of this, or about my premonition that I would be arrested.

After I returned from Suzhou, I was still translating a French novel. During that time, I finished a short story by Prosper Mérimée called “Mateo Falcone,” which is about a family on the island of Corsica. The father, Mateo, was a well-respected man and an expert marksman. He had a young son, about ten years old. A fugitive, trying to escape capture, gave the boy five francs and hid in their hayrick. Soldiers soon arrived and demanded the boy tell them where the fugitive was. The boy initially refused, but when the captain offered him a silver pocket watch, he finally gave in. To get the watch, he pointed out the fugitive’s hiding place. When his father returned, the captured man spat at Mateo’s door and cursed, “The home of a traitor!”

His father shouldered his rifle and told his son to follow him into the mountains. A single gunshot was heard, and he executed his own son.

You might think such a father is inhumane, but the story highlights the theme of trust and integrity, and how some people value it more than life itself.

I had just finished translating this story in October 1960 and was preparing to show it to Fu Lei. I assume this translation manuscript is still in my case file.

After our goodbyes in Suzhou, Lin Zhao stopped writing. Her letters couldn’t be delivered to my residence in Heiqiao in the countryside. A postman could come, but the address was complicated and the old house had no street number. Thus, Lin Zhao and I agreed that if she were to write, she would send the letters to my home on Xikang Road.

I always picked up all her letters from my home on Xikang Road. My mother and sister knew about it. They saw one letter arrive from Suzhou, and then another soon after. The letters were left on the kitchen counter on the ground floor. The envelopes had my name on them in very delicate, beautiful handwriting. They asked me who it was.

I told them it was Lin Zhao, a classmate from Peking University, from the Chinese department, and that she was in Suzhou. So they all knew who Lin Zhao was and that we were corresponding.

I could send letters from Heiqiao, but I had to go back to Shanghai to receive them. There were no phones back then, so I only knew if she had written when I went back to Shanghai. I went back often, from Heiqiao to Xikang Road, at least once a week, sometimes more. If I wanted to see if a letter from Lin Zhao had arrived, I would go back. Letters were the only way to communicate.

So, my family was very clear that the person who wrote to me often was Lin Zhao. Zhang Chunyuan’s letters were also sent to my home in Shanghai. On the day they arrested me in Heiqiao, the police also sent people to search my house on Xikang Road. The police officers also questioned a neighbor who lived in the attic on the third floor, a single old man. I didn’t know him well, but we were always polite to each other. During the search, the police asked the neighbor if Gu Yan had any unusual behavior. He reported to the police that I had burned letters on the third-floor balcony.

It’s true that I burned the letters I received from Liang Yanwu. I burned all the letters from Zhang Chunyuan, from other people, and all the letters from classmates I received in Shanghai. Only Lin Zhao’s letters—I couldn’t bring myself to destroy them. She put a lot of thought into her writing. The envelopes and stationery were very particular. She was the kind of person who treated letter writing as a serious task. That’s why I thought she might have feelings for me. I used to address her as “older brother” in my letters, but later changed it to “older sister.” As a result, she got angry again, as if I was overthinking things. I was also furious, but then she acted as if nothing had happened. Once in Suzhou, we walked to a courtyard, and she told me that it was quiet and lovely. It would be nice to buy a house here and spend our later years.

The old man’s third-floor attic was opposite a balcony, which was above the pavilion room. That’s where I burned things. He told them I was burning things, which is how the Jing’an police sub-bureau found out.

During my interrogation, they asked: “What did you burn?”

What good does it do to ask? I burned them already! It had to be whatever I said it was! I burned them, but which ones? How do you expect to get the answer out of me? It’s impossible. He knew I was lying and could only move on.

I burned all the other letters so as not to implicate anyone else! Only Lin Zhao’s letters I couldn’t bear to burn. I told her I had burned them, but in reality, I kept them all. The letters from Zhang Chunyuan, Liang Yanwu, and Xu Cheng, I didn’t keep any. Zhang Chunyuan didn’t keep any of my letters either. Only Lin Zhao’s letters, all of them, I hid in the attic. As for whether she burned my letters, I don’t know, but it’s very likely she didn’t; because she didn’t believe anything bad would happen.

Therefore, the interrogators were very clear about my relationship with her, the dates of our trips between Shanghai and Suzhou, what happened on which day, and where we met. “What were you and Gu Yan doing? It was all written in the letters.” Thus, the interrogators never asked me what kind of relationship I had with Lin Zhao.

If they hadn’t searched my house, she would not have been implicated. But as a result of the search, all her letters were taken. On top of that, the journal Spark also contained her poems. This is what drew her into the case.

Based on these letters alone, I think Lin Zhao’s letters should have helped her. The investigators surely had to ask her, “When did you start associating with Gu Yan?” This information was all in the correspondence—how many times I went, how many times she came. The letters contained absolutely no mention of political matters. The actions we planned had nothing to do with her. She also had no connection to the people and events in Wushan. Tan Chanxue met her once, but she didn’t know any of the others.

5. “Catch the Bad Guy”

They didn’t arrest me right away; they had been following me for at least half a month. I suspect they knew when I went to Suzhou. Sometimes, I would go to Zhoupu Town to buy some meat or other daily necessities, and when I looked back, it seemed like someone was following me. I ran into a distant relative on the road, and he even greeted me. Later, that relative was also investigated and asked what we had talked about.

Yes, I had already arranged everything with Lin Zhao and had hidden my things. I was mentally prepared to be arrested. I knew they were coming to get me. It was impossible to escape. Where could I even run to?

I was still living alone in the countryside. My house was on the west side of a courtyard, and my uncle’s house was on the east, but they weren’t there, so the house was empty. Suddenly, a relative came to me and said that the commune team wanted to rent a room for some people who had come down from the commune’s main branch. I told him the house wasn’t mine; it belonged to my uncle.

Later, a tenant, a Northerner, moved in. I could tell by his accent, which was obviously different from the local country folk. I was a bit suspicious. I also knew I couldn’t escape. They had already rented the house right across from me, in the same courtyard, to monitor my every move.

On the morning of October 18, 1960, at around 8 a.m., I had just finished breakfast. The commune secretary came first. When he saw I was home, four or five more people came in behind him. They immediately tied my hands behind my back and put handcuffs on me. I said to them, “I’m just a student. What do you think you are doing?” But in my heart, I knew this ending had finally come.

One of the men was decent. He took my leather coat from the wall and said, “Put this on!”

It was late October, and the weather was getting a bit cold. My hands were cuffed behind me, so I couldn’t put the coat on. He draped it over my shoulders. I left my home in Heiqiao, Waxie Town, and had to walk a distance to the riverside at a place called Liuzao Port, where a motorboat went to Zhoupu Town. There was only one boat a day, leaving at 9 a.m. Once we got on the boat, only two people stayed to escort me. The others didn’t get on; they went back to search my residence.

I had ducks and chickens at my house in Heiqiao, which were outside the door. I had also planted a lot of vegetables, including pumpkins.

When the boat arrived at Zhoupu Town, we had to get off and walk a bit to the long-distance bus station. It was close to noon. As we walked through the small streets of the town, I had the coat draped over me, my hands tied behind my back, and a large group of children following us, all shouting, “Catch the bad guy! Catch the bad guy!”

The long-distance bus didn’t have a fixed departure time. Before getting on, my escorts probably spoke to the driver and had me board first. I went to the last row and sat down, with the two men sitting next to me. There were at least twenty or thirty other passengers on the bus.

To get from Zhoupu to Shanghai, we had to cross the river. At that time, there were no tunnels or bridges. The bus first drove to Zhoujiadu by the Huangpu River. All the other passengers got off, but the two men with me were not in a hurry. I saw a jeep parked there. They waved, and the jeep came over. I got off the bus and into the jeep, and the two men came with me. I even heard them chatting and laughing in the car. Because the nationwide famine had already affected Shanghai, their conversation was about what to eat for dinner that night. They asked the drivers. There were two drivers.

The jeep crossing the river took at least fifteen minutes. When the car reached the other side, it drove directly to the entrance of the Jing’an police sub-bureau. It was already dark when we arrived. They escorted me into an interrogation room, which was already prepared. They had me sit on a small stool.

From what I remember, they probably unlocked my handcuffs after I went inside. One interrogator sat across from me, with two big men standing on either side, which is how most interrogations worked. The interrogator looked very young, probably just graduated from school, and was well-mannered.

They asked me questions, and I answered them. I knew this was going to happen.

They had arrested me in the morning and escorted me all the way here. I hadn’t had lunch or dinner. I was interrogated all night in the interrogation room. They had a late-night snack. I said I was hungry, and they gave me a steamed bun. I said I wanted water, and someone poured me some.

The interrogators changed shifts, but I just kept sitting there, undergoing continuous interrogation. Their faces were stony. I had already prepared myself for this. I had decided how to answer their questions.

I don’t remember what questions they asked now. Anyway, I wasn’t panicking at all. As the saying goes, if you open a restaurant, you shouldn’t be afraid of big eaters coming to dine. I had already expected this. I thought, “However many years you want to sentence me to, so be it.”

I basically told them the truth. Since I was there, and I had done it, I admitted it. But I didn’t talk about the process of founding Spark, or the plan to mail “On the People’s Commune” to party and government leaders in several provinces and cities. Of course, I didn’t mention those things. When they asked me about other things, I answered.

Around 8 or 9 p.m., someone suddenly came in. He said something to the interrogators, and they immediately became extremely happy. I understood: they must have found the things I had hidden. There was a very long ladder in my house leaning against a wall. I guess they saw it and became suspicious: “Why is there a ladder here?”

6. I Heard Lin Zhao Arrive

Lin Zhao, like me, was first imprisoned at the Jing’an sub-bureau detention center, six days after I was arrested. I knew she had arrived because female inmates had to walk past our cells to get to the women’s cells, which were at the very end of the hallway.

The original location of the Jing’an sub-bureau was a wealthy family’s garden villa from before liberation, typically only two or three stories high. However, these villas always had a basement, and that’s where the detention cells were located.

[The residence at 1550 Nanjing West Road, used by the Jing’an sub-bureau of the Shanghai Municipal Public Security Bureau, was formerly the estate of the late real estate magnate Cheng Jinxuan. The garden covers an area of 8,500 square meters, with two stone lions flanking the entrance. The garden features an octagonal courtyard house, three stories high, with a wide marble staircase in the center. Behind the courtyard, a four-story building with sixteen rooms was constructed, with the second and third floors connected to the courtyard.]

When we entered, we walked down a staircase from the ground floor. After a large iron gate, there was a hallway. One side of the hallway had a row of cells with iron grates. Most of the room was underground, with no windows. There was a narrow ventilation window with iron bars between the top of the wall opposite the grate and the ceiling. Looking out through the bars, you could see the street outside. I immediately knew we were in the basement. With only that narrow ventilation window, the lights were on all day and all night.

I’m not sure how many cells there were; they didn’t let you see. I was pushed into a room, and the iron door clanged shut. I stepped in, and the room was full of people. There were about twenty to thirty people, and I sat down next to the toilet. It was already the morning of October 19, and everyone in the cell was sitting upright.

At night, we slept on the floor. The other inmates had blankets, but I didn’t. However, with dozens of people squeezed into a small room, it didn’t feel cold. After a few days, they notified my parents, and my family sent a blanket.

The inmates were all kinds of people, constantly coming and going. One moment someone was released, and then new people came in. The cell was chaotic.

A few days later, Lin Zhao arrived. When they called someone for interrogation, they would call out their name. I heard someone outside shout, “Lin Zhao!” and then heard footsteps pass by our cell door. The two months I was held at the Jing’an sub-bureau detention center were truly miserable. During the day, you basically couldn’t move. The very small room held up to forty or fifty people at its most crowded. Every few hours, we were allowed out for a bit of recess, which was really just lining up and shuffling around the cell. Later, I learned that Shanghai’s detention centers were divided into municipal and district facilities. The latter, managed by the district public security sub-bureau, were smaller and only held temporary detainees, with a high turnover rate. The Jing’an sub-bureau detention center, where Lin Zhao and I were first held, was one of these district facilities. Later, during the Cultural Revolution, my sister was held at the Hongkou sub-bureau detention center, which was also a district facility.

Lin Zhao and I were soon transferred to Shanghai’s No. 2 Detention Center. When Lin Zhao was arrested later for a second time, she was sent to Shanghai’s No. 1 Detention Center. Both of these facilities were managed by the municipal public security bureau. The municipal centers were larger and could hold long-term detainees. The No. 1 Detention Center was in Nanshi and had existed since the 1930s as a detention center in the Chinese area outside the concessions. The No. 2 Detention Center was on Sinan Road and was the French Concession’s detention center (commonly known as the “French prison”).

I was held at the Jing’an sub-bureau detention center for about two months. At the end of 1960, I was transferred to the No. 2 Detention Center on Sinan Road. I later learned that Lin Zhao’s trajectory after her first arrest was the same as mine. In retrospect, this meant that our cases were considered significant and that we would not be released anytime soon. In fact, it was five years from indictment to sentencing. Although the names of me, Lin Zhao, and Liang Yanwu—three Peking University alumni—were on the same indictment, Lin Zhao and I never saw each other again, neither during transport nor during the trial. And while I was at the Jing’an sub-bureau detention center, I didn’t see Liang Yanwu either. It was only after I was transferred to the No. 2 Detention Center that I saw him during a recess and realized he had also been brought to Shanghai.

7. In the No. 2 Detention Center

When I was transferred to the so-called French prison on Sinan Road, also known as the No. 2 Detention Center, the conditions were much better—even better than those later in Tilanqiao Prison. The floors of the No. 2 Detention Center were well-ventilated, with large glass windows. There weren’t many people in each room; at the most crowded, there were four, sometimes three, but usually two. They never put just one person in a room. With four people, we’d be sleeping shoulder-to-shoulder in the very small room, which was just long enough for us to lie down and fit a toilet at the end. In the morning, everyone had to fold their blankets precisely (a practice called “internal affairs”), and the blankets couldn’t be unfolded during the day. When the guards were strict, we weren’t even allowed to sit on our blankets for comfort. We spent all day sitting on the hard ground, which was very difficult. I used a bundle of clothes as a cushion. A guard would come over and yell, “Hey! Get rid of that cushion!”

The four of us inmates always sat by our bedrolls. If we saw someone coming, we’d tell each other who it was. We gave our main supervisors nicknames: one was called “Cruiser,” another “Battleship,” and another was nicknamed “The Mobile Government,” because in their lectures, they always talked about the “People’s Government.”

Sometimes, the guards would sneak along the iron grates to peek at what we were doing. Usually, they walked on the opposite corridor. The structure of the entire building was like a ship’s cabin: there were rooms in the center, a surrounding hallway, and a wire mesh between that hallway and the cells’ own corridor. Wooden walkways connected the two corridors, so you could see the ground floor from the fourth-floor corridor. Most nights, the guards walked the opposite hallway because it was safer. You see, if they walked along our side, someone inside might be able to reach a hand out and grab them... that was probably their thinking.

From the window opposite our cell, we could see Guangci Hospital. It was Shanghai’s first hospital for infectious diseases. There was a large grassy area there, and we could see people having visits in a small pavilion, with families dropping off things for the patients.

I thought of my parents, my brother, and my sister. They had no idea why I had been arrested, and I couldn’t tell them. My parents must have been extremely worried, and my brother and sister were certainly being implicated because of me. Every time I thought of this, my heart ached, but there was nothing I could do.

For some reason, inmates at the No. 2 Detention Center were often moved between rooms. From the third floor to the fourth, and the fourth to the fifth. I stayed there for more than four years. Shortly after I arrived, I got some good news: we could write requests for deliveries, which meant our families could send things in once a month. This was called “subsistence aid,” but we couldn’t see our families, just like the patients with infectious diseases at Guangci Hospital. Family members would give things to the administrators, who would then pass them on to me. Lin Zhao’s experience at the No. 2 Detention Center should have been the same as mine.

8. Lin Zhao Wrote “My Thought Process”

Half a century later, I learned about Lin Zhao’s intellectual journey after her first arrest from the case files found by Tan Chanxue. Lin Zhao was arrested on October 24, 1960. After being transferred to the No. 2 Detention Center, she was released on medical parole on March 5, 1962. On October 14, 1961, she wrote “A Review and Examination of My Personal Thought Process” (hereafter referred to as “My Thought Process”). On the first page of the photocopy, Tan Chanxue noted that this document came from “Gansu Province Tianshui Public Security Bureau Enforcement Division Pre-Trial File” for Zhang Chunyuan’s case.

Of course, we were all required to write these kinds of ideological summaries. I wrote one too. I didn’t write much at the Jing’an sub-bureau detention center; there, they just wanted you to confess. They gave you a piece of paper, and after you confessed, you pressed your handprint on it and followed a simple procedure. They wouldn’t ask you to write a long treatise. There were no tables or beds in the cell; we sat on the floor during the day and slept on the floor at night. Everyone used their own blanket, half for a pad and half for a cover.

After being transferred to the No. 2 Detention Center, it had a floor, but still no tables. The long confessions were written there because the detention period was so long, and after a while, there was nothing new to confess. Once you were done confessing, they would ask you to write an ideological self-critique, and they’d give you a pen and paper. It’s possible they called me to an office to write at a table there.

Based on the content of Lin Zhao’s “My Thought Process,” I believe it is authentic and was indeed written by her. However, the photocopied document is very blurry. I can only rely on the text that Tan Chanxue later edited and included in The Collected Works of Lin Zhao to understand her views. In the photocopy and the edited draft, I noticed a lot of ellipses, which made me wonder: Did the case workers from Shanghai add them themselves? Because inmates would not use ellipses in a confession. Since I haven’t seen the original document, I’ll leave this question for you to investigate. Also, I believe the case workers who came to Shanghai were mainly there to get my confession. They just copied Lin Zhao’s “My Thought Process” as a side note. Lin Zhao’s self-critique confirms my earlier point: Lin Zhao and I had many ideological commonalities regarding the Spark case, and both Zhang Chunyuan and I were her important friends. However, she had limited knowledge of the actions we planned to take and genuinely did not want to get involved. As I said before, she kept a certain distance. Simply put, she should not have been arrested at all. She didn’t have much to do with the Spark case. If I were to be self-reflective, I could even say that I was the one who harmed her. If I hadn’t mimeographed “The Seagull,” if I hadn’t been so close to her, and if I hadn’t kept the thirty-plus letters she sent me, it’s very likely she wouldn’t have been arrested for the Spark case.

In this self-critique, she mentions my name in a few places.

The first time she mentioned me, she said that through me, she learned about the general situation at Peking University and Lanzhou University after the Anti-Rightist Campaign and that we shared a common ideological foundation.

“Gu Yan and others had already invited me to the Northwest to visit, but I was unable to get away and was afraid of drawing attention. Later, he also fell ill and returned to the South, which was a convenient coincidence. Through our contact, we quickly communicated and exchanged information on the general situation at Peking University and Lanzhou University since the Anti-Rightist Campaign.”

But after talking about this, she felt that she should “exist independently and fight independently” and not care too much about organization. She said that I actually understood this point. As I mentioned before, Lin Zhao had no organizational ties with us, and this document proves it again. This is where she mentions my name for the second time:

“I didn’t emphasize this much to Gu Yan. First, because there was no practical need to emphasize it at the time, and second, since he also came from Peking University, he had a rather strong ‘Peking University mindset,’ so it wasn’t necessary to stress it.”

The third time she mentioned my name was in reference to “The Seagull.” It’s clear that after discovering the mimeographed copies of “The Seagull” at my house, the Jing’an sub-bureau initially focused on this poem during Lin Zhao’s interrogation. But Lin Zhao didn’t care much about it either. The mimeographing was not her idea; the poem was originally meant to be passed around privately. She didn’t mind friends reading it, but she clearly stated that there was no need to mimeograph and distribute it. I can see from this that she was quite angry with me. Because of my mimeographing, her poem went from underground writing to public writing. She believed this was not a mutually beneficial act but the opposite—that it would harm both the author and the readers. She wrote:

“When I was in Beijing, I had hand-copied it to circulate and give away, but that’s a different matter. That could still be considered within a legal scope; at most, you could criticize the poem itself. But once it’s printed, even if it’s just mimeographed, it seems attention-seeking and sensational. It gives off a look of making a big deal out of it, when in fact it’s not a big deal at all. ‘A shoe without a sole is just for show, lighting a lamp on the moon is an empty name.’ I won’t do it. Otherwise, I would have participated in the distribution and reprinting of propaganda materials with the underground party back in the day. It’s not like I don’t know how; just talking about printing, besides needing ink, what else do you need? Just pin the carved stencil to a tabletop with a thumbtack, and it will print just the same. How difficult can it be! But I just didn’t get around to doing it.”

I see a few layers of meaning in her words, primarily a defense of herself. In other words, first, she was unaware of what I was doing. Second, even if she had known, she wouldn’t have agreed. She used a very dismissive tone to belittle the significance of our mimeographing “The Seagull,” making our actions sound pointless, like “attention-seeking” and “making a big deal out of it.” Her message was, “What’s the big deal? I’ve done things like that before, and I was much more skillful, but I just chose not to do it this time.”

Why didn’t she do it? She went on to say that printing secret propaganda was risky for both the printer and the reader. And besides, what new ideas did we have to show people? If it was just common knowledge, it wasn’t worth printing.

When I read these parts, I thought about how we planned to mimeograph Zhang Chunyuan’s “On the People’s Commune” and send it to high-level cadres. To Lin Zhao, this seemed like a cliched old topic with no value whatsoever. And we misunderstood her; we thought she was scared, but she wasn’t—she didn’t participate because it wasn’t worthwhile. “If it’s not worthwhile, I won’t do it.” This is how she wrote it: “But my position was misunderstood, which made me quite angry—I’ve already come this far, would I still cling to my own life?”

Were Lin Zhao’s words her true thoughts, or was she downplaying her involvement to reduce her sentence?

I believe both are true. Since she was writing based on the demands of the case workers, and it was a self-critique, it’s understandable to include some boilerplate language that aligns with the general situation. But I disagree with Lin Zhao’s negative view of our actions.

Furthermore, this self-critique also reveals the logic behind why Lin Zhao would be imprisoned again after her release on medical parole from the No. 2 Detention Center.

So what was the key factor? I think Lin Zhao misjudged the situation. It wasn’t just her; I misjudged it too. Another factor for me was a practical consideration: I wanted to get out alive. But Lin Zhao was single-minded in the pursuit of her ideals. This was related to her ideology, experience, and personality. In these aspects, we were different.

Reflecting on my youth now, and comparing it with Lin Zhao’s thought process, this difference becomes even more apparent. When we were together, in that hazy emotional state I mentioned before, we rarely talked about politics. When I gave her a copy of Spark, with so many articles critiquing current events, of course she knew our ideological leanings. Didn’t she understand my attitude toward reality from my “Publisher’s Note”? It was an unspoken understanding; there was no need to repeat ourselves. When we were together, we talked about everyday things.

Looking back, the degree to which we were involved in politics was also different.

From a family perspective, my parents were non-partisan. Although my aunt and uncle were senior Communist cadres, we were mainly influenced by my father and maintained a certain distance from the ruling party and party politics. As I told you, when Stalin died, they wanted us to wear black armbands, and we refused. But at that time, Lin Zhao wrote a poem called “Stalin Inspires Us to March Forward Forever,” which had lines like “Even if we lost our own parents / It would not pain us more than today!” Lin Zhao’s family had a stronger political background. She herself had participated in the Communist Party’s underground work in high school, and her old classmates confirmed she had joined the Communist Party in high school. In “My Thought Process,” she also stated that she was “a person who actively participated in the student movement led by the underground Party before liberation and once had a relationship with the Party organization.” It is said that she later lost her Party membership because she did not follow orders to evacuate from Suzhou. In “My Thought Process,” she confessed:

“But since I followed the Party during the years of Red Terror and offered my pure adolescent passion to the Party, from a personal standpoint, I should not hesitate to bear full political responsibility for all of the Party’s actions: whether they are good governance or tyranny.”

As for me, from high school, I hoped to devote myself to physics research. I was not interested in politics and certainly didn’t want to get involved in it. In February 1980, Liang Yanwu and I were both in Shanghai, waiting for our cases to be reviewed. On the 9th, we went to Suzhou together to attend a memorial service for Lin Zhao’s mother. In the car, I met Ni Jingxiong for the first time. She knew I was a co-defendant in Lin Zhao’s case and asked me, “You’re a physics major, how did you get involved in politics?” I replied, “It’s not that I wanted to get into politics; it’s that politics came to get me.”

Furthermore, Lin Zhao also had a certain reserve that I didn’t realize when I first read “The Seagull.” She was not the simple poet I had imagined. She had more social experience and had been through more than I had. She participated in land reform and worked at a newspaper for nearly two years. I, on the other hand, went from school to school, from undergraduate to graduate studies. If I hadn’t gone to Tianshui for labor and observation, my social experience would have been even more limited. I hadn’t had the chance to deeply understand many of her political thoughts.