威权国家已经结盟,抗争者能团结起来吗?——专访“共谋星图”策展人、缅甸流亡艺术家Sai

Authoritarian States Have Formed an Alliance, Can the Resistance Unite? — Exclusive Interview with the Curator of “Constellation of Complicity” and Exiled Burmese Artist Sai

作者:张彦

By Ian Johnson

本采访稿原文为英文。

The English original follows below.

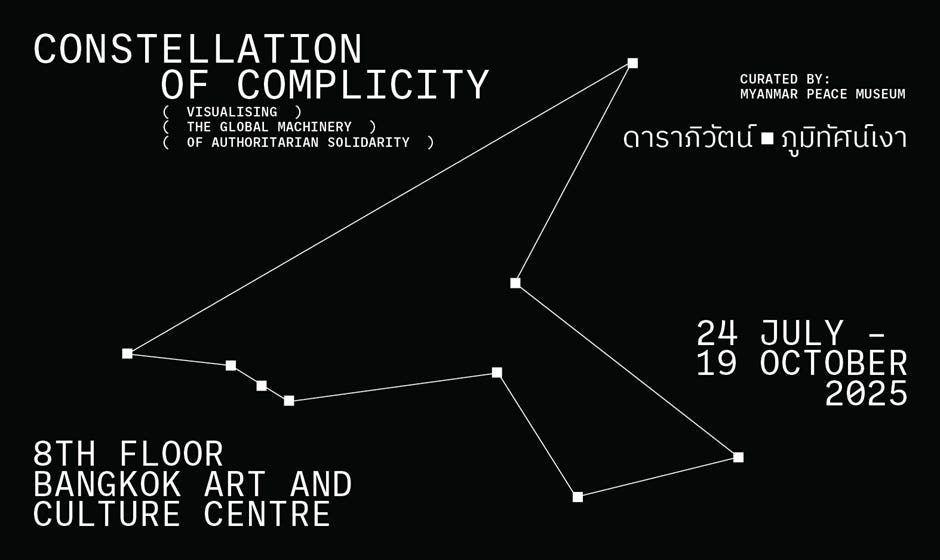

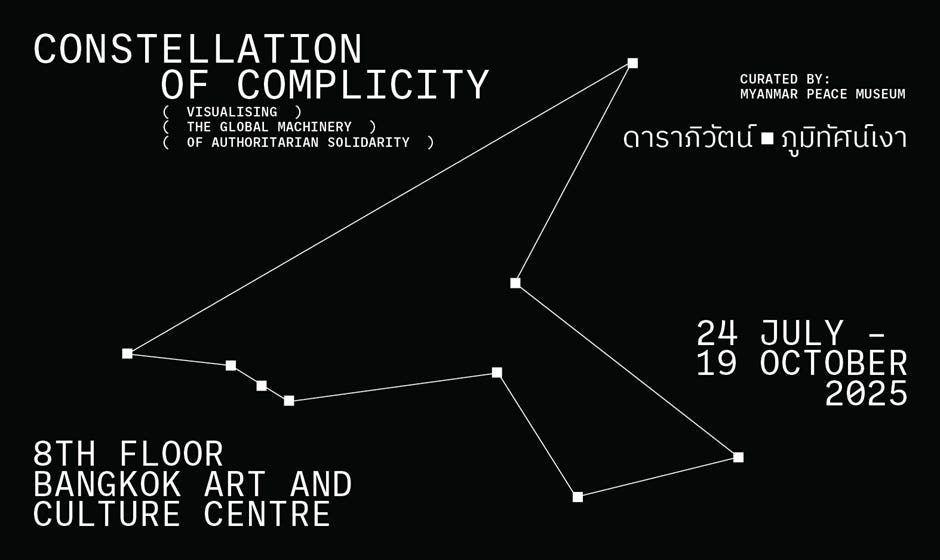

今年七月,一个引人注目的展览在泰国首都曼谷开幕。这个名为“共谋星图:全球威权联盟的可视化呈现”(Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity)的展览,由缅甸艺术家Sai参与策展,展出了来自全球七个地区艺术家的作品:香港、伊朗、缅甸、俄罗斯、叙利亚、西藏和新疆。所有这些地方都由威权政府所掌控。换句话说,这些政权在思想、言语和行动上,经常是互相撑腰、相互支持的。

展览于7月24日开幕,但仅仅两天后就遭到打压。泰国当局强迫主办机构——曼谷艺术文化中心(BACC)——对涉及中国的作品进行审查。有四位艺术家——来自香港的张嘉莉(Clara Cheung)和郑怡敏(Gum Cheng Yee Man),西藏裔美国艺术家Tenzin Mingyur Paldron,以及来自中国新疆地区的艺术家Mukaddas Mijit——名字被涂黑,部分作品被移除。文化中心还移除了西藏旗和一面通常与东突厥斯坦独立相关的旗帜。

更令人震惊的是,作为策展人之一的Sai先生本人受到威胁。在工作人员告诉他泰国警方想要讯问他之后,他逃离了泰国。10月14日,中国民间档案馆创始人张彦致电身在伦敦的Sai先生,讨论了“共谋星图”展览,以及他在流亡之后的计划。

采访稿经过编辑,以求简洁清晰。

问:你是什么时候开始构思这个展览的?

答:是在2021年,缅甸军方发动政变,推翻了昂山素季政府的时候。一个香港朋友联系我,问:“发生什么事了?你还好吗?”我当时就说,你知道的,情况很糟。他问:“有多糟?”我说:“真的很糟。糟到我父亲凌晨三点被绑架。”

问:你父亲是缅甸掸邦的首席部长,对吗?

答:是的。我母亲当时被软禁。我父亲被绑架的方式,就像教科书里写的政变那样。直到今天,他仍在监狱里。所以我们去了迪拜,在那里被困了两个月。后来我拿到了英国签证,因为我2019年曾在伦敦大学金史密斯学院做访问学者,他们说我可以回去继续访学。

通过和香港人的接触,我开始意识到:我们需要一起合作。在国外让我能鸟瞰整个局势。因为我们跟中国是邻居,而中国基本上是给缅甸这场政变开了绿灯的国家,俄罗斯也是,所以,只要我们无法对抗这两个“歌利亚”(巨人),我们就永远赢不了。

所以大概是在2022年,我在伦敦,和香港人一起在中国大使馆前抗议。我看到乌克兰人也在那里。我当时就想:缅甸也是链条上的一个环节,因为缅甸军方得到了中国和俄罗斯的授权。从那时起,我开始明白,我们不能独自战斗。

问:中共是否深度介入了缅甸政治?

答:去年,中共基本上是绑架了掸邦抵抗运动的领导人彭大顺,因为他的部队——缅甸民族民主同盟军(MNDAA)——成功地击败了军政府。同盟军攻占了我的家乡腊戍。中共与同盟军关系良好,叫彭去云南开会。然后他们就把他软禁了。中国政府告诉他:“如果你不放弃占领的城镇,我们就不放你走。”

问:中国为什么要这么做?

答:因为腊戍是个巨大的补给站。所有中国商品都必须经过那里。所以它又被还给了军方。那里的一切都受到中共的监控。

问:回到你的流亡生活,你到底是什么时候离开缅甸的?

答:从2021年2月1日到7月,我父亲先是被关在一个军事大院里,然后被送进了监狱。接着我母亲被拘留。真正促使我离开的是我妻子可能被闭路电视拍到和参与抗议运动的人们交谈。我们在仰光市内东躲西藏。我们申请了签证,但只能去迪拜。2021年11月27日,我们抵达了伦敦。

问:你在英国待了多久?

答:八个月。在这段时间里,我在金史密斯学院举办了个人作品展,也和香港人一起办展。我们和其他流散群体一起,在曼彻斯特和谢菲尔德也办了展览。然后我搬到了法国,法国给了我们一年的紧急签证。

正是在法国,我真正发展出了全球团结的意识。在巴黎,你可能知道一个叫做“异议者俱乐部”(Dissident Club)的地方。它其实是一个酒吧,由一位逃离巴基斯坦情报部门的巴基斯坦记者经营。他对我来说就像兄弟一样。我们开始认识世界上其他的异议人士,包括“暴动小猫”(Pussy Riot)的成员——Taisiya Krugovykh和Vasily Bogatov,他们也参加了“共谋星图”的展览。

问:你为什么在2023年又回到泰国?

答:在法国,我觉得我没有成功接触到法国的高层。所以我想,好吧,不如我们回泰国去?因为我们离开国家的目的是要为自己的国家发声,但我们没能实现这一点。

问:但泰国对来自缅甸的流亡者来说很危险。

答:是的,对于我来说,除了缅甸本身,它是世界上最危险的国家。泰国政府一直在系统性地迫害来自缅甸的社会活动家,并且也支持缅甸军方,可谓是深度共谋。但我们在法国真的很沮丧。所以最后我们还是决定回到东南亚。

问:我们再聊聊这个展览。你和你的妻子K一起共同策展的,对吗?

答:是的,这个展览基本上是我和我妻子五年流亡生活的体现。

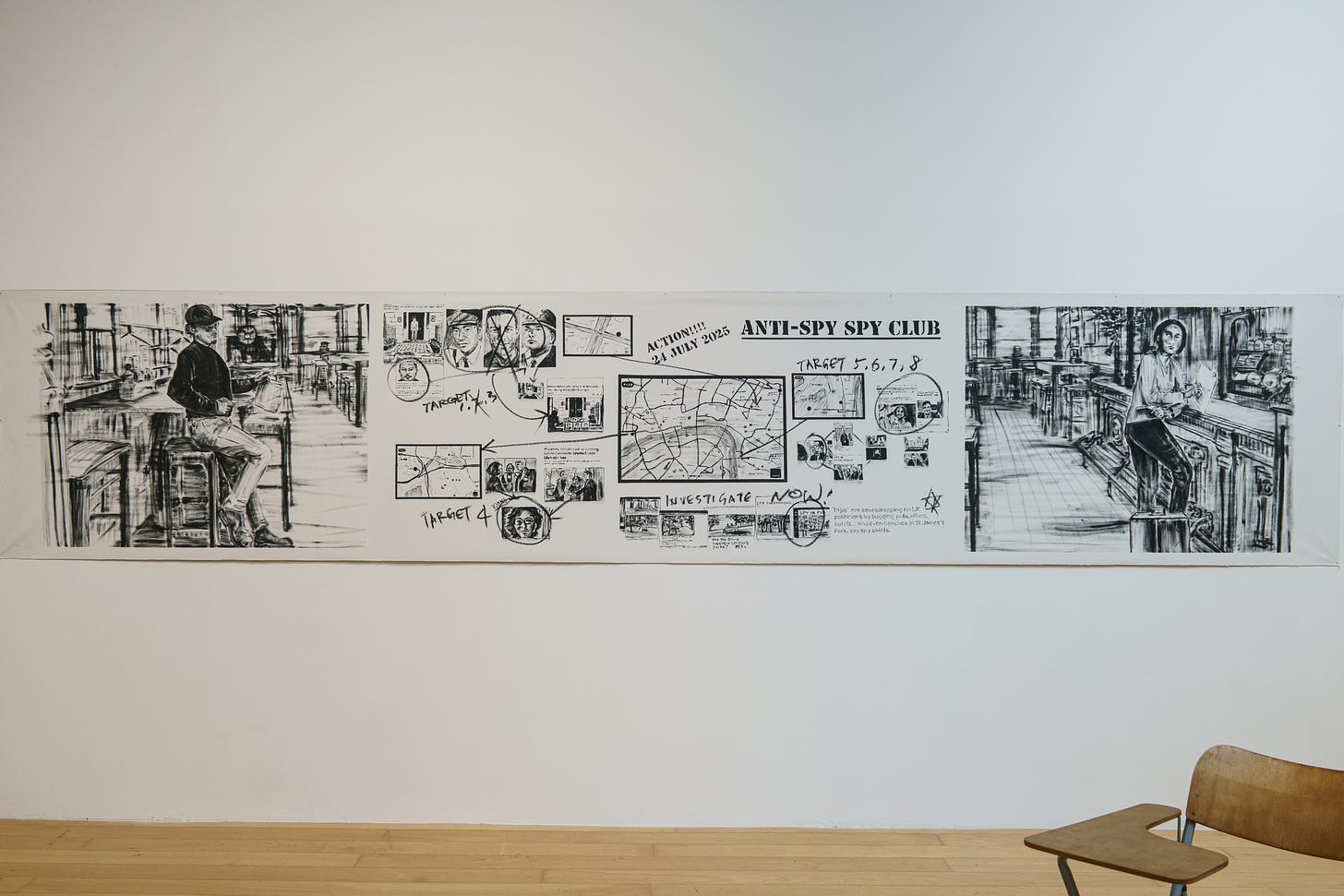

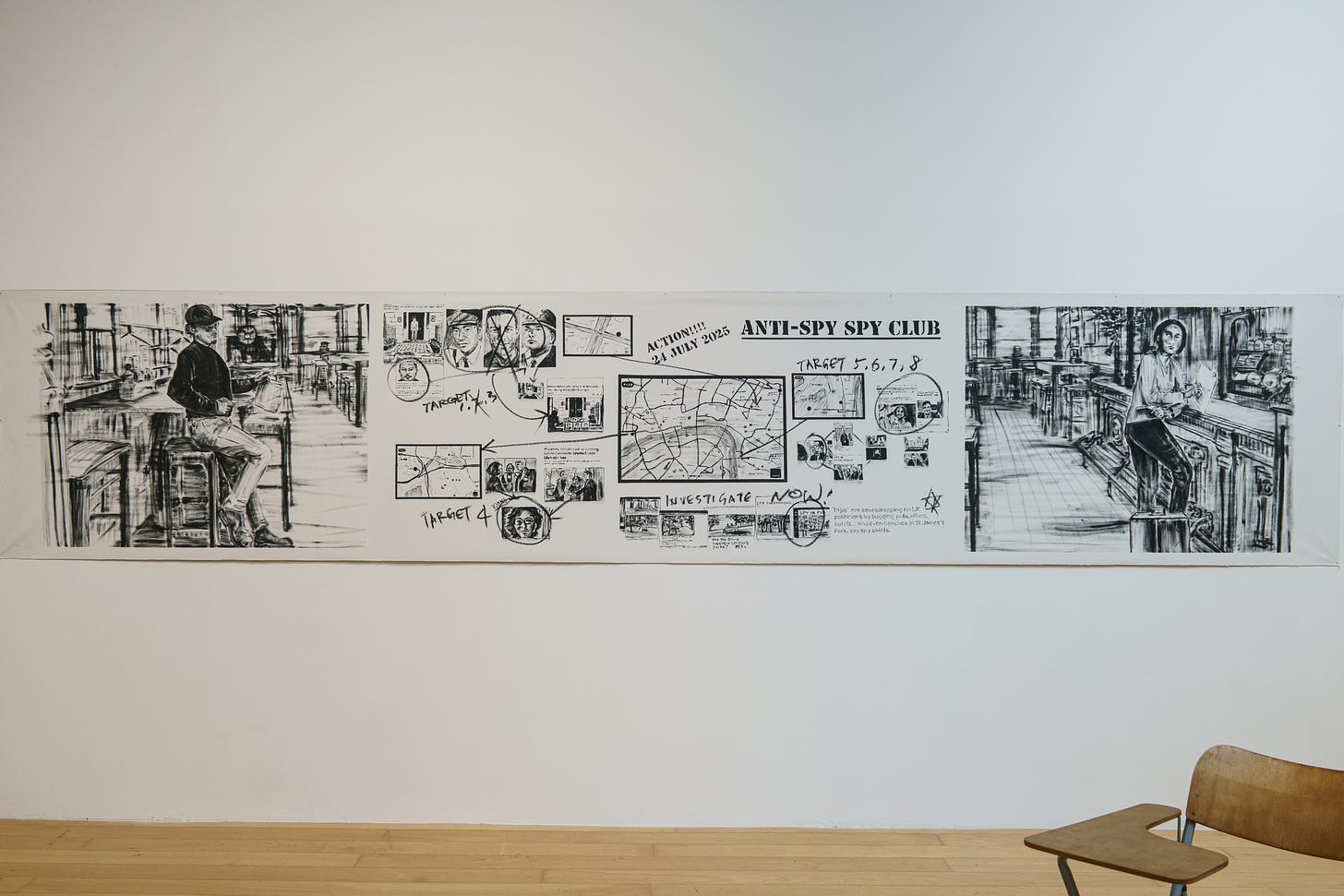

我们想描绘出全球的压迫地图,让世人看到这些独裁者是如何互相帮助的。我们之所以想描述这些压迫,是因为主流媒体并没有真正做到这一点。他们往往只关注一个国家或一次悲剧。媒体的弱点就是缺乏这种“制图”机制。我跟BACC(曼谷艺术文化中心)的一位策展人聊了聊,她说:“你为什么不自己来做呢?”

我简直不敢相信。我说:“真的吗?”因为我以前尝试过很多次。我跟欧洲的博物馆谈过。他们从来不喜欢这个主意,因为他们不想跟中国打交道。

问:我喜欢这个标题“共谋星图”。你是怎么想出来的?

答:这很有意思。我们原先用的工作标题是“描绘全球压迫地图”。但问题是,这个话题和标题都太沉重了。展品本身已经够直接、够扎眼了。我们需要一些更具诗意的词汇,所以我们选定了“共谋星图”。

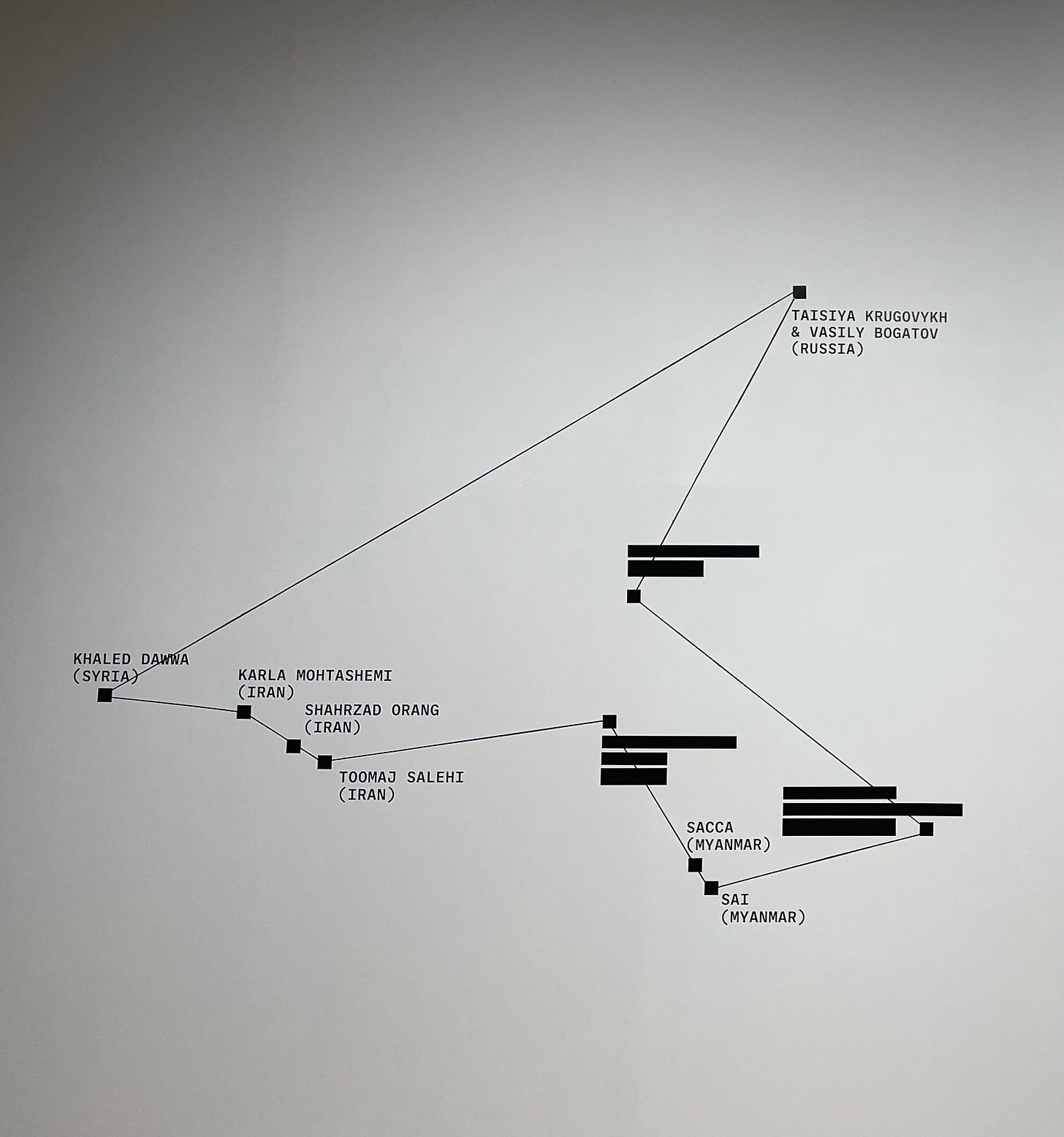

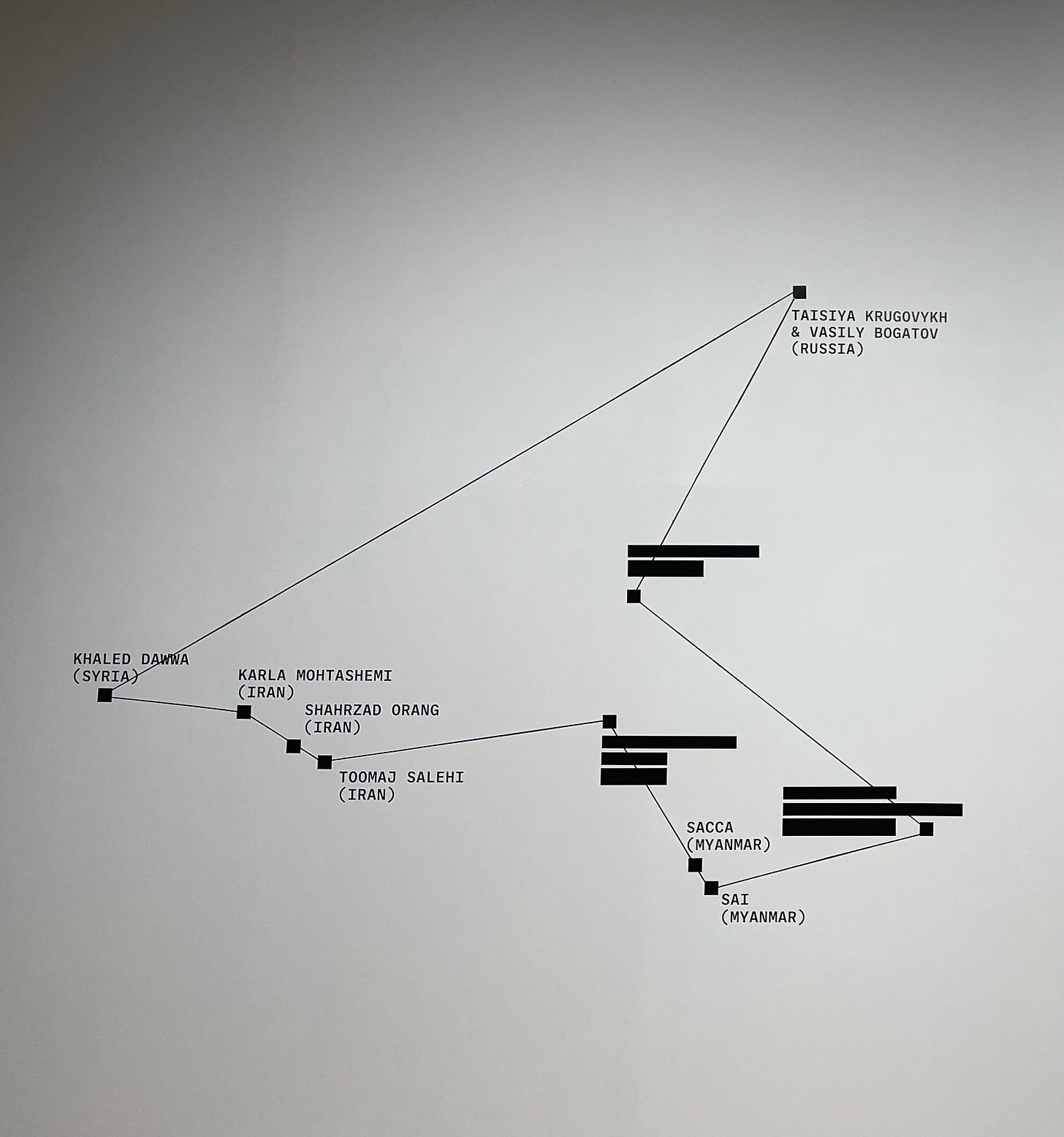

问:展览中有一张很棒的图表,显示了不同国家之间的联系。

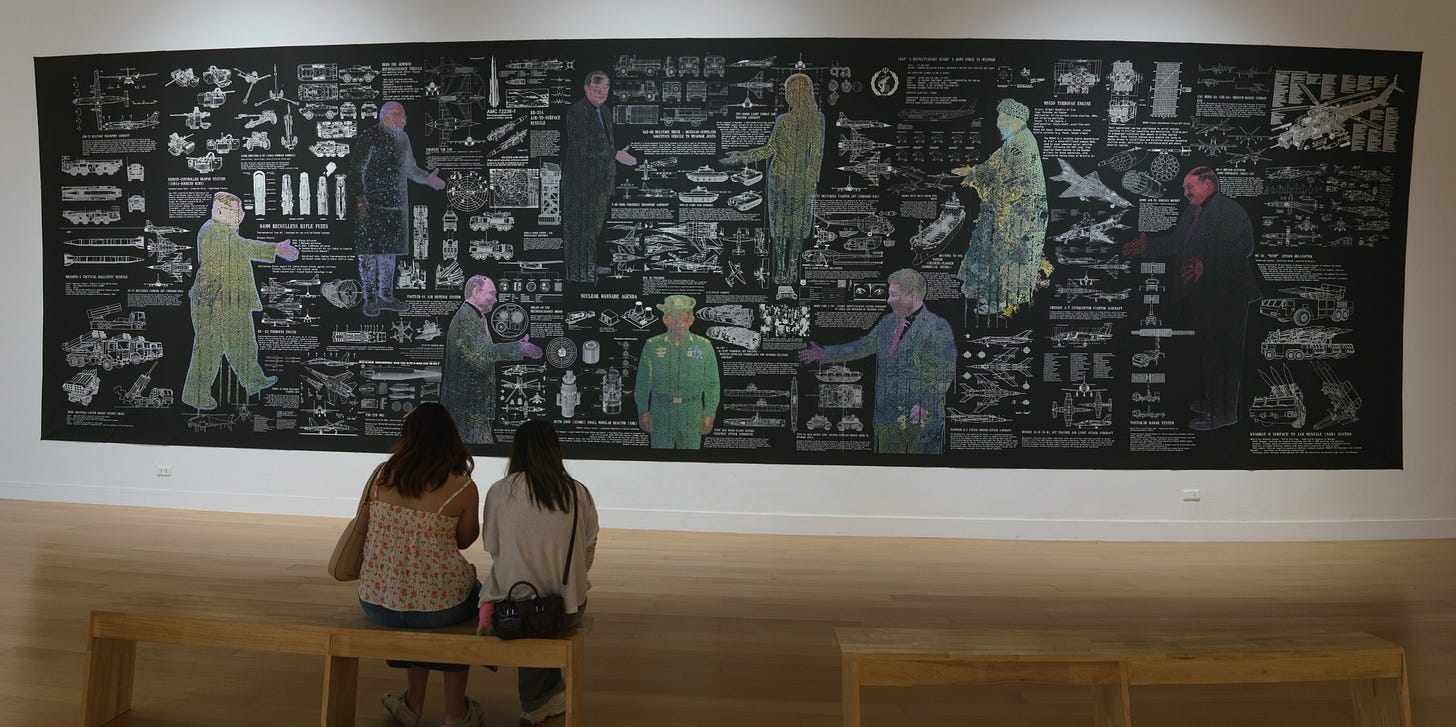

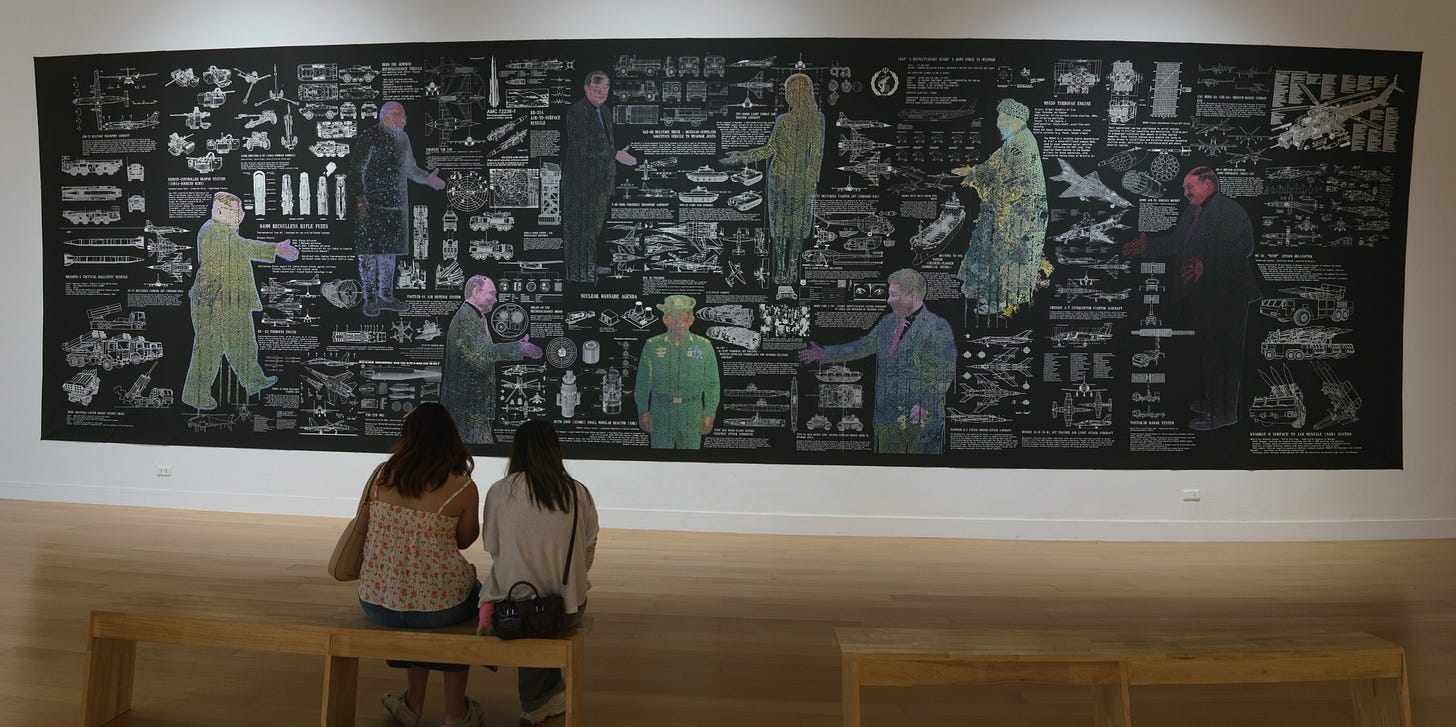

答:当你走进展览,看完所有的开场白后,你会看到俄罗斯艺术家Taisiya Krugovykh和Vasily Bogatov的作品。那是一个摇篮曲的音景装置。歌词讲述了一个故事:

俄罗斯给缅甸提供装备,

维持它的政权清醒和稳固:

米格-29和苏-30战斗机在飞行,

划破云层,展现一番威胁的景象。

Mi-24和Mi-35武装直升机在盘旋,

为地面战争而制造。

“铠甲-S1”防空系统守卫陆地和天空,

阻止无人机和导弹飞过。

这说的是让缅甸军方能继续运作的军火交易,但它是以摇篮曲的形式呈现的。然后你走到伊朗和叙利亚。在所有这些地方的背后,都有推动变革的武器、技术和物资,还包括所有这些政权原理图和蓝图。所以,展览的这一开场部分,正是“共谋星图”的体现。接着你继续走,会看到其他艺术家的作品。

问:这是一个很有意思的想法,因为它源于你对全球团结的体验,但它同时也展现了压制政权之间的团结。你的展览中有西藏和维吾尔艺术家,但为什么没有来自中国的汉族艺术家呢?

答:我们想把世界上每个国家都包括进来,但实际上我们不能,因为我们没有足够的资金。这就是为什么这个展览本应是双年展。它本应每两年举办一次。这是我们打算做的。这样我们就能邀请到更多的艺术家。

问:在艺术家名单上,你的名字旁边有一条黑色的横杠,就像是被涂掉了一样。这是为什么?

答:我不能再使用我的全名了。不然我的家人可能会面临后果。

问:Sai这个化名是什么意思?

答:基本上,它没有任何特殊意义。Sai字面上的意思就是“先生”。缅甸名字都很长,所以我们经常互相称呼“Sai”:“你好,Sai。你怎么样,Sai?”所以当人们问:“你认识缅甸一个叫Sai的人吗?”大家会说:“当然认识!”每个人都叫Sai。

本期推荐档案:

中国民间档案馆线上主题特展——“共谋星图:全球威权联盟的可视化呈现”(电脑浏览器观展,效果最佳)

Authoritarian States Have Formed an Alliance, Can the Resistance Unite? — Exclusive Interview with the Curator of “Constellation of Complicity” and Exiled Burmese Artist Sai

By Ian Johnson

In July, a remarkable exhibition opened in the Thai capital, Bangkok. Co-curated by the Burmese artist known as Sai, the “Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity” showed works of artists from seven parts of the world: Hong Kong, Iran, Myanmar, Russia, Syria, Tibet, and Xinjiang. All are run (or in Syria’s case were recently run) by authoritarian governments in league with each other. In other words, regimes that often buttress each other in thought, word, and deed.

Two days after it opened on July 24, the show came under attack. Thai authorities forced the host institution, the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, to censor works having to do with China. Four artists—Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng Yee Man of Hong Kong, the Tibetan-American author and artist Tenzin Mingyur Paldron, and the Uyghur artist and filmmaker Mukaddas Mijit—had their names blacked out and some of their works removed. The center also removed the Tibetan flag and a flag often associated with Uyghur independence.

More remarkably, Mr. Sai felt under threat and—after staff told him that Thai police wanted to question him—fled the country. On October 14, the China Unofficial Archives editor Ian Johnson called Mr. Sai in London to talk about the show, its aims, and his plans now that he is in exile.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

When did you start thinking about the show?

In 2021, when the coup [by the Burmese military against the government of Aung San Su Chi] happened, a Hong Kong friend reached out to me and asked what happened? Are you okay? I’m like, you know, things are bad. And he said how bad? I’m like, really bad. Like my father got abducted at 3 a.m. bad.

Your father was the chief minister of Shan State in Myanmar.

Yes. And my mother was under house arrest. He got abducted like in a coup textbook. And still today he’s inside the prison. So we got to Dubai and were stuck there for two months. I then got a United Kingdom visa because I had been a fellow there at Goldsmiths College in 2019 and they said I could come back to continue the fellowship.

Through my contact with Hong Kong people I began to realize that we need to work together. By being abroad I had a bird’s-eye view of the situation. We can never win because we are neighbors with China and China is the one who basically green lighted the coup. Also Russia. So as long as we cannot fight against these two Goliaths, we will always be defeated.

So it was around 2022 in London I was with Hong Kong people protesting in front of the Chinese embassy. And I saw Ukrainians there too. And I was like; Myanmar is part of this too. It’s a link in the chain. The Myanmar military is being empowered by China and Russia. Myanmar is like a link between these two. So from that, I came to see that we cannot fight this fight alone.

Has the CCP been heavily involved in Myanmar politics?

Last year, the CCP basically kidnapped the resistance leader in Shan state, Peng Daxun, after his forces, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) were successful against the junta. The MNDAA had overrun my hometown, Lashio. The CCP has a good relationship with the MNDAA and called him to Yunnan for a meeting. Then they put him under house arrest. He was told by Beijing that if you don’t give up the captured town, we won’t let you go.

Why did China do that?

Because Lashio is a huge supply town. All Chinese goods have to go through that. So it was given back to the military. Everything there is monitored by the CCP.

Going back to your life in exile, when exactly did you leave Myanmar?

First my father was kept in a military compound from February 1, 2021 to July, when he was sent to prison. Then my mother was detained. What triggered me to leave was that my wife might have been caught on camera talking to people involved in civil disobedience. We went on the run inside Yangon. We applied for a visa and could only get to Dubai. On November 27, 2021, we arrived in London.

How long did you stay in the U.K.?

Eight months. During this time I was showing my work as a solo exhibition at Goldsmiths and also together with the Hong Kongers. Along with other diaspora groups, we had shows in Manchester and Sheffield. Then I moved to France, which gave us an emergency visa for a year.

It was in France where I really developed a sense of global solidarity. In Paris you might know a place called the Dissident Club. Actually, it’s a bar run by a Pakistani journalist who escaped from Pakistani intelligence. He’s like a brother to me. We started to meet other dissidents in the world, including members of Pussy Riot–Taisiya Krugovykh and Vasily Bogatov, who are in the exhibition.

Why did you go back to Thailand in 2023?

In France I didn’t think I was successful in reaching French political leaders. So I was like, okay, why don’t we just go back to Thailand? Because the fact that we get out of the country is to advocate for our country, but we could not fulfill that.

But Thailand is dangerous for exiles from Myanmar.

Yes, for me, it is the most dangerous country in the world besides Myanmar itself.

The Thai government has systematically persecuted Myanmar activists. They have been hugely complicit in supporting the Myanmar military. But we were really depressed in France. And so at the end, we decided to go back.

Let’s talk a bit more about the show. You and your wife, who goes by the name “K,” co-curated this.

Yes, this exhibition is basically a manifestation of my wife’s and my exile life of five years.

We wanted to map the global oppressions, how the dictators are supplying each other. We want to map the oppressions because mainstream media doesn’t really do this. They tend to just focus on one country or on one tragedy at a time. The weakness is that there’s no mapping mechanism. I talked to a curator at the BACC, and she said, why don’t you do it?

I couldn’t believe it. I was like, really? Because I tried to do it many, many times before. I had spoken to European museums. They never liked this idea because they don’t want to deal with China.

I love the title. How did you get it?

It’s funny. We were going by a working title of “mapping global oppression.” But the thing is, it is such a heavy topic and title. The exhibits are in your face. We needed something more poetic. So we workshopped it and chose “constellation of complicity.”

The exhibition has an amazing graphic showing links between the different countries.

When you enter the show, after all the opening statements, you see the Russian artists Taisiya Krugovykh and Vasily Bogatov. It’s a sound installation of a lullaby. The lyrics tell a story:

Russia supplies Myanmar with gear,

To keep its regime in control and clear:

MiG-29s and Su-30s in flight,

Cut through the clouds, a menacing sight.

Mi-24s and Mi-35s soar,

Helicopters made for the ground war.

Pantsir-S1 guards land and sky,

Stops drones and missiles flying by.

It’s about the arms deals that keeps the Myanmar military afloat but it’s like a lullaby. Then you walk to Iran and Syria. Behind all these places are the transformative arms, technologies and supplies, all the schematic drawings and blueprints of it. So this initial walk in the exhibition is a manifestation of a constellation of complicity. Then you go on and see the artists’ works.

It’s an interesting idea because it grew out of your experience with global solidarity, but it also shows the solidarity of repressive regimes. You have Tibetan and Uyghur artists in the show, but why no Han Chinese?

We want to include every country in the world but realistically, we cannot because we don’t have the funding. That’s why this exhibition is supposed to be like a biennial. It’s supposed to go every two years. That is what we intend to do. Then we can get in more people.

On the list of artists, your name has a black bar next to it, as if your name is redacted. Why is that?

I cannot use my full name anymore. Otherwise my family may face repercussions.

What does Sai mean?

Basically it doesn’t mean anything. Sai literally means mister. Burmese names are long, so we often call each other Sai: Hello Sai. How are you Sai? So when people say do you know a guy in Burma called Sai people will say, yes, of course. Everyone is called Sai.

Recommended archive:

Online digital exhibit now hosted by the China Unofficial Archives website: “CONSTELLATION OF COMPLICITY: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity” (for optimal viewing experience, use a browser on a computer)