民主的意义和有意义的民主——重读《历史的先声》

Holding the Party to its Word: Rereading the 1999 Classic, The Herald of History

作者:贾民

By Jia Min

The English version of this newsletter follows below.

中国是一个民主国家吗?

这个问题对很多人来说,答案显而易见,甚至问出这个问题都会让部分人觉得滑稽可笑。但对另外很大一部分人,比如当下的很多中国中小学生来说,答案是“是的”,因为世界上最权威的书籍——教科书明确写道:“我国是人民当家作主的国家。人民是国家的主人。国家的权力来源于人民。”(人教版《高中思想政治必修2》)

这样的语言不止存在于教科书。《中国的民主》白皮书,对于中国当下的“全过程民主”制度,有这样的描述:“全过程人民民主,实现了过程民主和成果民主、程序民主和实质民主、直接民主和间接民主、人民民主和国家意志相统一,是全链条、全方位、全覆盖的民主,是最广泛、最真实、最管用的社会主义民主。”

任何在义务教育里长大的中国青年,对这种语言恐怕都耳熟能详。一个需要通过高考实现人生跨越的文科生,不仅需要牢记这些正确的话,而且要在政治考卷的简答题里,深刻地、全面地提供它的逻辑和阐释,要敏锐、准确地辨别与党的话语看似相近但实际上是错误的说法,例如:“中国是一党专政的国家,是对是错?”一个好学生会马上意识到这道题的陷阱在哪里,因为政治老师已经讲过:我们国家是一党执政、多党参政,绝对不是一党专政,这是一道常考题,几乎每年高考都会出现……

即便是虔诚学习的“小镇做题家”,也需要花费巨大的脑力、调动大量的储备,来理解政治书上的话。比如,为什么一定不是“一党专政”,大多数人只能求助于简单世俗的理解。因为“专政”听起来就不好听,在任何语境里,“专政”恐怕都不是一个好词。不过,中华人民共和国宪法第一条中的“人民民主专政”,是个什么意思?为什么“人民民主”又要跟“专政”放在一起?

民主、专政等政治概念,对于很多在义务教育里长大的中国人而言,成为需要费劲脑力才能略知一二的谜团。民主基本的、朴素的意义,在需要像ChatGPT一样踩点得分的政治简答题里,被架空了。民主到底是什么,民主的社会怎样运转,民主制度下的公民怎样行动?——这些本应简单的问题,成为大多数中国人无法回答也没有思考过的难题。

民主,真的这么难以理解的吗?难道是需要人们付出巨大的脑力才能准确把握的吗?现代中文的语言里,是否存在对民主基本的意义最为基础朴素的阐述?是否存在美国《独立宣言》一样的语言,其对于基本人权的阐述,面向所有人,感召所有人?——答案是肯定的。这些语言的集合,曾于二十多年前在中国正式出版,并短暂自由流通,书名为《历史的先声》。

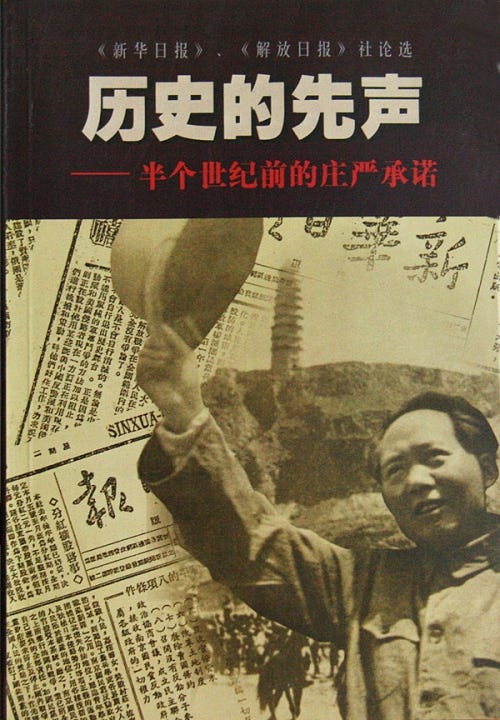

《历史的先声:半个世纪前的庄严承诺》由作家、时评人笑蜀整理成书,摘录了1949年以前,毛泽东、周恩来、刘少奇等中国共产党领导人与《新华日报》和《解放日报》等中国共产党党报所发表的关于民主、自由、人权等政治理念和普世价值的论述。本书于1999年由汕头大学出版社出版。出版者在前言中写道:

“重读50年前的文字,使我们看出,当今境外对我党、我国的谩骂、污蔑,是没有历史根据的。早在西方政要走上历史舞台前,我党前辈革命家、理论家就已经是卓越的民主、人权战士……在民主与独裁、自由与专制、人权与镇压之间做出了他们的选择,并为次殊死奋斗。”

《历史的先声》收录的文字,不同于当下中国官方的语言风格——比如大量使用排比句,大量重复制造节奏感,以及一系列“专业术语”的加持,譬如“全链条、全方位、全覆盖”,让读者稀里糊涂、不明觉厉——1949年前的中国共产党使用的语言简单、直接、易懂、幽默,简单引用以下几例(这样的语言在《历史的先声》中比比皆是):

“每一个在中国的美国士兵都应当成为民主的活广告。他应当对他遇到的每一个中国人谈论民主。美国官员应当对中国官员谈论民主。总之,中国人尊重你们美国人民主的理想。”(1944年毛泽东在延安与来访的美国官员的谈话。)

“有人说: 中国虽然需要民主,但中国的民主有点特别,是不给人民以自由的。这种说法的荒谬,也和说太阳历只适用外国,中国人只能用阴历一样。”(1944年《新华日报》社论《民主即科学》。)

“黄(炎培)先生说得好:民主是不成问题的,一定要民主,怕的只是假民主。”(1944年《新华日报》短评。)

“目前推行民主政治,主要关键在于结束一党治国。”(1941年《解放日报》社论。)

“所以,有两种报纸。一种是人民大众的报纸,告诉人民以真实的消息,启发人民民主的思想,叫人民聪明起来。另一种是新专制主义者的报纸,告诉人民以谣言,闭塞人民的思想,使人民变得愚蠢。”(1946年1月11日《新华日报》创刊八周年纪念文章。)

毛泽东所说的推崇美国民主的话,并没有在毛选中被“和谐”。当年《新华日报》和《解放日报》的文章,今天在图书馆和网上数据库中也可以被查阅。而这些篇章被聚到了一起之后,为什么就被中国官方视为洪水猛兽?如此旧的文字,难道具有变革性的力量?

《历史的先声》被查禁,这本身就是极端荒谬的。当然,在“起来,不愿做奴隶的人们!”都会被屏蔽的当下,中国人对这种荒谬恐怕早已见怪不怪。审查制度,正是要排除异己,消除异端,通过局限语言来禁锢思想。一个政权的审查制度,怎能将伟大领袖视为异己,将自身喉舌视为异端呢?

现代极权的一大特征,就是“说一套,做一套”,言行不一,却让人有种说的就是做的,做的就是说的,且言行皆正确的错觉。

制造错觉,就必然先让语言失去意义。在争夺权力时,共产党语境下的“民主”,也就是《历史的先声》中所摘录的“民主”,是接近于毛泽东所说的美式民主,是一人一票的民主,是有意义的民主。然而,在掌权后,共产党的“民主”变成了“人民民主专政”中的“人民民主”,也衍生出了“全过程民主”,甚至还有“中国最民主论”,即中国比其它(真正的)民主国家还民主。

不过,电视里外国的民主,好像都是要人们排着队,轮流进入一个专门投票的地方做点什么。中国人排队,大多只是为了超市结账,或是过各种安检,以及前几年的捅鼻嗓做核酸,就没有一次是为了投票选举出个国家领导人。

没有一人一票的选举,也没有基于一人一票选举的权力交接制度,甚至都没有可靠的党内权力继承规则,何谈民主?

这样对“民主”语义的摧残,正像《1984》中,“旧话”中的思想被“新话”中不含思想的正统所代替的过程一样。当“民主”一词丧失了意义,争取民主的行动本身也就失去了根基。这也意味着,中国人追求民主、人权、自由等普世价值,早已不是从零开始,而首先需寻求“由负归零”,因为从零开始的状态里,语言还没有失去意义,价值还没有被扭曲,“新话”还没有扰乱人们对现实的认知。

《历史的先声》所做的,正是集结了曾经鲜活的、未被破坏过的关于民主、自由、人权等价值的基本意义的语言,又因为其话语本身出自共产党的奠基者们,强有力地挑战了当下被权力所垄断的政治话语,正所谓以子之矛,攻子之盾。

中国官方对于《历史的先声》的恐惧,正是“新话”对“旧话”的恐惧,是官话、套话对有生命力的、有活力的语言的恐惧。而现在中国官方对“新话”的不断完善,痴迷于造新词、造新句,以宏大、抽象、复杂、语义模糊的辞藻,架空语言,架空现实,垄断叙事,废除思想,正是要最大限度挤压有生命力、有意义、有思想的语言的生存空间。

如今,我们要追求中国共产党在1949年以前所追求的民主、自由、人权,就需要认清当下被权力垄断的话术,并留意官方在用语言试图创造和正常化怎样的现实。我们也需要重新发现、使用和保护如《历史的先声》中收录内容一样的鲜活的文字,构建有意义的、不被权力垄断的语言,并记得那些“历史的先声”中——民主的含义、自由的含义、人权的含义。

本期推荐档案:《历史的先声:半个世纪前的庄严承诺》

Holding the Party to its Word: Rereading the 1999 Classic, The Herald of History

By Jia Min

Is China a democratic country?

For many people, the answer to this question is so obvious that even asking it seems funny. But for a large part of the Chinese population, especially schoolchildren, the answer is “yes,” because the most authoritative book they know–their textbook–asserts: “Our country is a country in which the people are the masters of their own house. The people are the masters of the country. The power of the state comes from the people.” (High School Politics (Required) Volume 2, People’s Education Press.)

Such language is ubiquitous. The white paper “Democracy in China” has this to say about China’s current system of “whole-process democracy”: “Whole-process people’s democracy integrates process-oriented democracy and results-oriented democracy, procedural democracy and substantive democracy, direct democracy and indirect democracy, and people’s democracy and the will of the state; it is a full-chain, all-encompassing, and full-coverage democracy, and it is the broadest, truest, and most functional socialist democracy.” (For English readers who also understand Chinese: note how the last sentence in the official English translation in the above hyperlink does not translate the original Chinese word for word and summarizes instead.)

Any Chinese youth who received compulsory education is familiar with this language. A humanities-track student who depends on China’s college entrance examination for upward mobility must not only memorize these correct words, but also elaborate on their logic in the short-answer questions in the politics exams. Students also have to keenly and accurately identify words that seem similar to the party’s discourse but are in fact erroneous. For example: “China is a one-party dictatorship, true or false?” Good students will immediately identify the trap because their politics teacher will have prepared them well by explaining: China is a country with one-party rule and multi-party participation in politics; it is definitely not a one-party dictatorship.

Even a student who studies religiously needs to spend a lot of brain power to understand the concepts in the politics textbook. For example, for why China is not a “one-party dictatorship,” most people can only resort to a simple secular understanding. It’s because “dictatorship” does not sound good, and “dictatorship” is not a good word in any context. However, what is the meaning of “people’s democratic dictatorship” in Article 1 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China? Why is “people’s democracy” put together with “dictatorship”?

Political concepts such as democracy and dictatorship have become a mystery to many people who went through China’s compulsory education. The basic meaning of democracy has been hollowed out through the short answer questions in the politics exams that need to be churned out in bullet points like ChatGPT. What exactly is democracy, how does a democratic society function, how do citizens in a democracy act? These supposedly simple questions have become difficult ones that most Chinese people never thought of and cannot answer.

But is democracy really so difficult to understand? Is it something that requires a great deal of brain power to grasp accurately? In the modern Chinese language, is there a simple statement of the meaning of democracy? Is there a language like the Declaration of Independence of the U.S., whose exposition of basic human rights is open to all and appeals to all? The answer is yes.

A collection of such language was officially published and briefly circulated freely in China more than twenty years ago. The book is called The Herald of History: The Solemn Promise of Half a Century Ago. This book contains excerpts of pre-1949 discourses on political concepts and universal values such as democracy, freedom, human rights. The authors? None other than Chinese Communist Party leaders, including Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Liu Shaoqi, along with editorials by Chinese Communist Party newspapers, such as Xinhua Daily and Liberation Daily. Organized into a book by the writer and commentator Xiao Shu, it was published by Shantou University Press in 1999.

The publisher wrote in the foreword:

“Re-reading the words of 50 years ago makes us see that the invectives and slanders against our party and our country from outside the country today have no historical basis. Long before western dignitaries took to the stage of history, our party’s revolutionaries and theorists were already outstanding fighters for democracy and human rights. They made their choice between democracy and dictatorship, freedom and autocracy, human rights and repression, and fought to the death for these values.”

The words in The Herald of History are different from the language of today’s Chinese authorities, whose extensive use of parallel phrasing, rhythmic repetitions, along with a series of technical terms, such as “full-chain, all-encompassing, and full-coverage,” make readers confused yet in awe. The language used by the Chinese Communist Party before 1949 was simple, direct, easy to understand, and humorous, to quote a few of the book’s many examples):

“Every American soldier in China should be a living advertisement for democracy. He should talk about democracy to every Chinese person he meets. American officials should talk about democracy to Chinese officials. In short, the Chinese respect the American ideal of democracy.” (Mao Zedong with visiting American officials in Yan’an, 1944.)

“Some people say: Although China needs democracy, democracy in China is somewhat special in that it does not give freedom to the people. The absurdity of such a statement is the same as saying that the solar calendar applies only to foreign countries and that the Chinese can only use the lunar calendar.” (1944 Xinhua Daily editorial, “Democracy is Science.”)

“Mr. Huang [Yanpei] said it well: democracy is not a problem, for there must be democracy, but what we are afraid of is false democracy.” (Short commentary in Xinhua Daily, 1944.)

“The key to the present implementation of democratic politics lies in ending one-party rule.” (Editorial in Liberation Daily, 1941.)

“So there are two kinds of newspapers. One kind is the newspaper of the people, which offers the people the true news, inspires them to think democratically, and tells them to smarten up. The other is the newspaper of the new authoritarians, which tells the people rumors, closes their minds, and makes them stupid.” (Article commemorating the eighth anniversary of the founding of Xinhua Daily, January 11, 1946.)

Today it’s still possible to find these words scattered and separate–in Mao’s selected works, for example, or on online newspaper databases. But taken together the words were too much and the book was banned two months after being published.

The very fact that The Herald of History has been censored is absurd. Of course, at a time when “Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!” can be censored, the Chinese people are probably not so easily surprised. Censorship’s goal is to suppress dissent and eliminate heresy, confining thought by restricting language. How can a regime’s censorship deem its dear leaders as dissidents and regard words from its own mouthpiece as heresy?

One of the characteristics of modern totalitarianism is the inconsistency between its words and deeds, but it gives people the illusion that what it says is what it does, and what it does is what it says, and that both its words and deeds are correct.

To create such an illusion, language must first be rendered meaningless. When the Chinese Communist Party competed for power, it talked about “democracy” as it did in The Herald of History. This was the democracy close to the American ideal as described by Mao Zedong, the democracy with “one person, one vote,” and democracy that is meaningful. However, after coming to power, the Chinese Communist Party’s “democracy” became “people’s democracy” and “whole process democracy.” The party even proclaims China as the largest democratic country and even more democratic than other major democracies.

Democracy in foreign countries is portrayed on television as people queuing up and taking turns to enter a voting booth, while Chinese people only line up just to check out at the supermarket, or to go through various security checks, or to have their noses and throats poked for COVID-19 tests. Not once did the Chinese people ever come out in the hundreds of millions and cast their votes to elect a national leader.

When there is no one-person-one-vote election, no system of power transfer based on such elections, and not even any reliable rules of power succession within the party, how can China speak of democracy?

This destruction of the meaning of “democracy” is similar to Orwell’s 1984, when the thoughts in “Oldspeak” were replaced by the thoughtless orthodoxy of “Newspeak.” When the word “democracy” loses its meaning, the struggle for democracy itself will be missing its foundation. This also means that the Chinese people’s pursuit of democracy, human rights, freedom, and other universal values is not starting from zero. They must seek to fight from negative to zero. This is because in the state of starting from zero, language has not yet lost its meaning, values have not yet been distorted, and “Newspeak” has not yet twisted people’s perception of reality.

What The Herald of History does is to gather the once vivid and undisturbed language of democracy, freedom, human rights. Because its words come from the founders of the Communist Party, it strongly challenges the current political discourse monopolized by power.

The Chinese authorities’ fear of The Herald of History is precisely Newspeak’s fear of Oldspeak, the fear of empty words for lively words. Now Chinese authorities are continuing to perfect their Newspeak with new words and new concepts, using grandiose, abstract, complex, and semantically ambiguous rhetoric to hollow out language and reality, monopolize the narrative, and abolish thought, minimizing the living space for language that is lively, meaningful, and thoughtful.

Nowadays, if we want to pursue the democracy, freedom, and human rights that the Chinese Communist Party promised the Chinese people before 1949, we need to recognize the current rhetoric monopolized by power, and pay attention to what kind of reality the officialdom is trying to create and normalize with language.

We also need to rediscover, use and protect living words such as those included in The Herald of History, to construct a meaningful language that is not monopolized by power, and to remember what the words in The Herald of History tell us–the meanings of democracy, freedom, and human rights.

你好,我觉得这篇文章写得非常好,很有价值,请问我能否转载至我的专栏?

»毛泽东早在1941 年就指出:“国事是国家的公事, 不是一党 一派的私事。因此, 共产党员只有对党外人士实行民主合作的义务,而无排斥别 人、垄斯一场的权利。”“共产党的这个同觉外人士实行民主合作的原则,是固定不愁的, 是永远不变的。”我国实行的是共产觉领导的多党合作铺麼。共产觉是执政觉,民主党 派是参政觉。这是符合中国国情的社会主义政觉制度。亡有利于中国共产觉和各民主觉 派团绪合作、互相監督,共洞致力于建设有中国特色的社会主义和统一祖国、振兴中华的 伟大事业。«

王绍光,林尚立,孙文学,王沪宁,孙关宙,刘学华,李维康,陈军.《政治的逻辑:马克思主义政治学原理》. 上海:上海人民出版社,2004.

我认为中国共产党非常巧妙地利用民主元素来维持各地区的合法性,但并不将基本方针完全交给纯粹的民主进程。这样,中国一方面牢牢掌控自己的目标,另一方面在协调的民主框架内产生了对更好想法的重要竞争。

请不要误解我:这与我对民主的理解不同。中国对民主的利用更像是一个受控环境,一旦民主进程试图破坏其自身基础,随时可以进行干预——就像一个沙盒。这是一个不同的系统,但中国在这方面取得了成功,这是你们可以引以为豪的。

我在这个系统中看到的唯一困难是为政治局培养的新精英。他们远离亲身经历过去混乱时期的痛苦和泪水,对新精英来说,这段历史是随着时间推移必须保存和克服的东西。但这也带来风险,他们可能变得过于宽容,试图在令人印象深刻的商品世界及其在剩余价值光照下的流通中为大众寻找救赎。这意味着他们可能会满足于已取得的繁荣。

挑战在于创造具有中国价值观的社会主义,提供新形式的劳动和商品。也许是时候每周抽出一天,不是在私营部门工作,而是从事有益于文化公共利益的活动,生产不被剩余价值"金牛犊"所缠绕的公共产品。通过缓慢、谨慎的改革——如中国人所说的——"摸着石头过河"。