我与林昭(下篇): “她走上了夏瑜的道路” (顾雁回忆录选登)

“She Chose a Martyr’s Path”: Lin Zhao and Me (Part 2) (Selected Excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoirs)

顾 雁 口述/修订

艾晓明 撰稿/整理

Narrated & revised by Gu Yan

Written & compiled by Ai Xiaoming

The English translation follows below.

编者按:

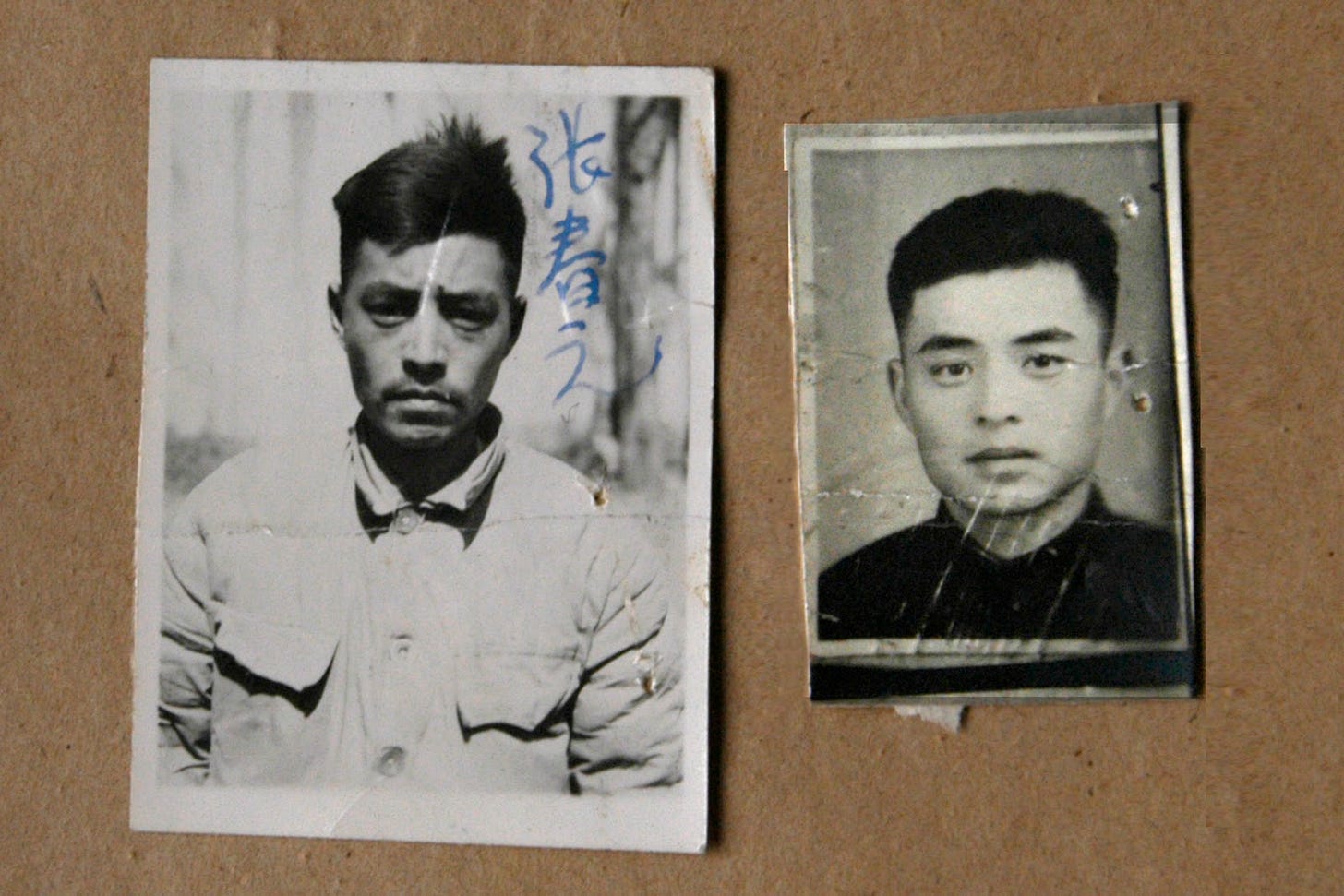

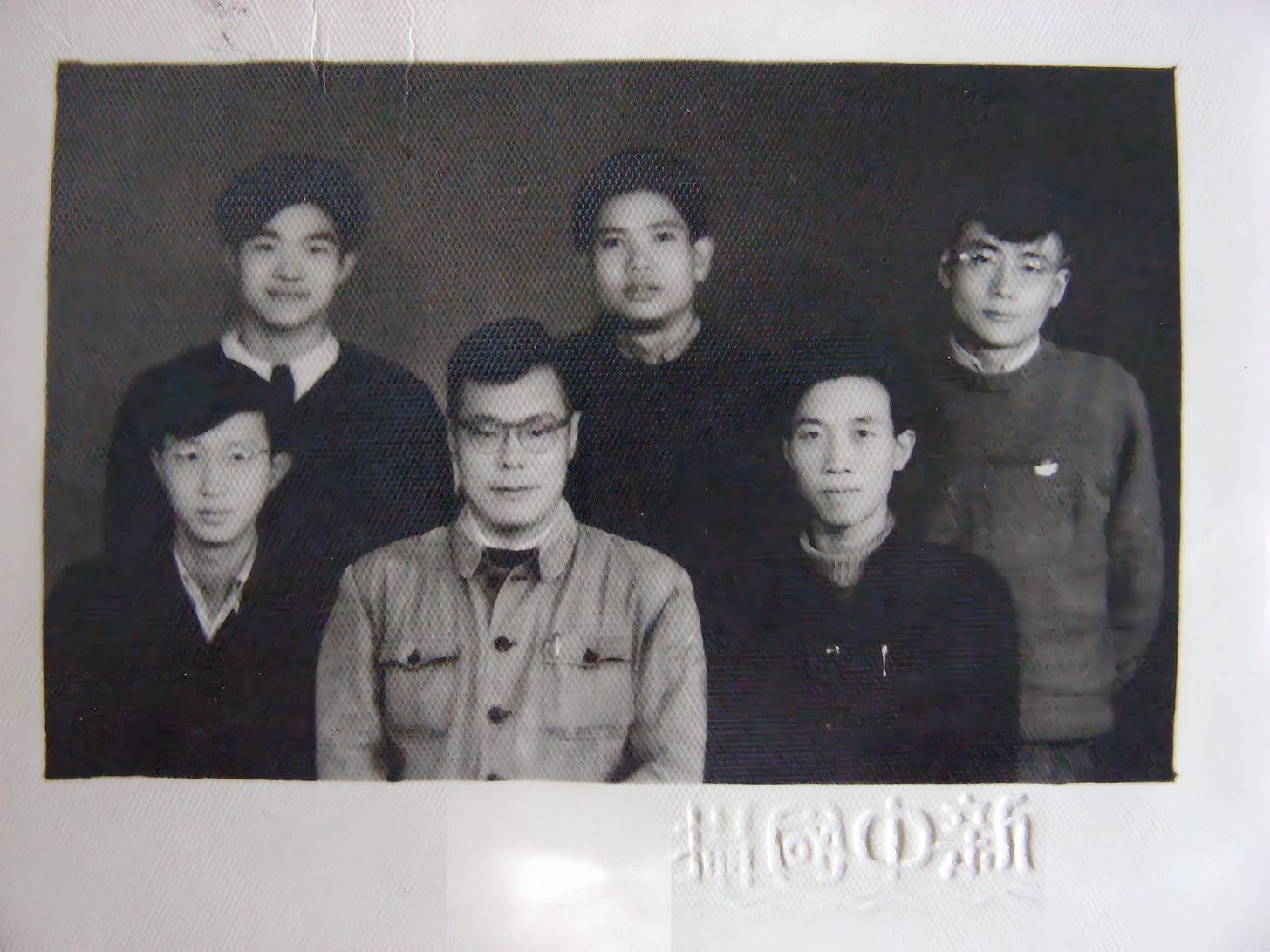

大饥荒时期地下刊物《星火》的创刊人顾雁教授,于2025年8月23日度过了他的九十岁生日。顾雁一生坎坷,1960年因“星火案”在上海被捕,与林昭、梁炎武同案,1965年被判处17年徒刑,后到青海服刑,1980年平反后到兰州大学任教,与顾淑贤结为伉俪。顾雁于2001年从中国科技大学退休,是理论物理研究专家,著有《量子混沌》一书,现居合肥。

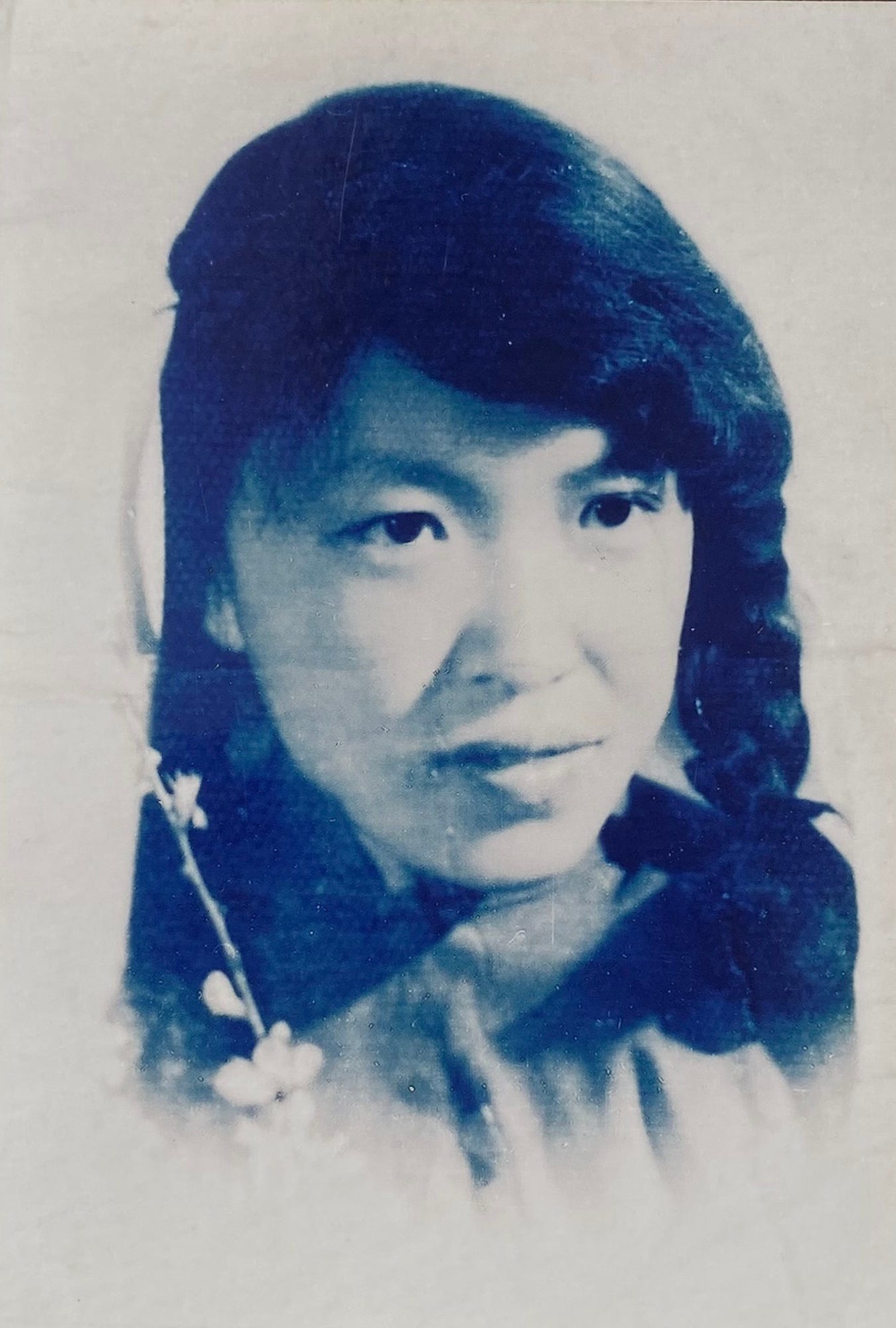

顾雁在北京大学物理系读书时,与长他三岁的林昭(中文系新闻学专业学生)并不相识。1959年《星火》在天水秘密创刊前,顾雁曾亲手刻印林昭的长诗《海鸥》,在朋友们之间散发,并将她的另一首诗刊发在《星火》第一期上。1960年他回上海探亲期间,与林昭见面,后频繁往来三、四个月,两人之间产生情愫,往来信件数十封,后顾雁、林昭先后被捕。林昭取保候审,重被收监后遭遇非人折磨,于1968年4月29日惨遭杀害。

本文是艾晓明教授编撰整理的《顾雁回忆录》之一部分,分上、下两篇。耄耋之年的顾雁在其中详细回顾了自己与林昭的交往,以及林昭与《星火》的关系等。这是自《星火》诞生66年以来,作为创始者的顾雁首次以第一人称,对自己一生经历,以及“星火往事”的一次全面回顾。其中他与林昭之间的情感、囚禁中听闻她已牺牲的“悲痛惭愧”,都感人至深。作为亲历者和见证者,顾雁的回忆,也有极高的历史价值。

中国民间档案馆得以首次刊发,深感荣幸。

另外,关于本文题目——夏瑜是鲁迅笔下的革命者,原型为秋瑾。林昭被杀害后,正在青海服刑的顾雁得知消息,悲痛不已,在和家人通信中,因高压审查而无法表达心情,只能暗示说“她走上了夏瑜的道路”。

本文分为上下两部分刊发,第一部分已发表于中国民间档案馆网站和Substack平台。

一、林昭被保外就医

从1961年初到1965年5月31日判决下来,我在二所被羁押了四年五个月。我、林昭、梁炎武,我们三个人被列为同一个案子,同时被起诉。我保留了1962年8月1日的起诉书和1965年5月31日的判决书,在这两份文书里,我们三个北大校友同案,我名列第一,是为首犯。在起诉书中,我和梁炎武的状态都是“现在押”,林昭是保外就医,“暂住茂名南路159弄11号”。

【这份由上海市静安区检察院拟定的起诉书,下面有三个编号:“沪静检诉字第416、423、431号”。后来收入《林昭文集》里林昭对起诉书的批注,不是这一份,而是单独对林昭的起诉,上面只有林昭的名字。在1964年11月4日对林昭的起诉书上,署名与1962年8月1日对顾雁、林昭、梁炎武的起诉书相同,乃“检查员吴泽皋”。林昭以血书加注:“一九六四年十二月二日上午七时五十分收到”。这份起诉书编号为“(64)沪静检诉字第423号”,由此可见,423编号属于林昭。由此推测,顾雁编号为416,梁炎武编号为431。由于三人被列为同案,故在1962年最早的起诉书上,包括了这三个编号。而1965年对三人的判决另有一个编号,即“一九六二年度静刑字第一七一号”。】

1962年8月,我在起诉书上看到,林昭已经被保外就医了,那时我是很为林昭高兴的。我内心的负疚感终于减轻了,她本来就没干什么事,是我把她牵连进来的。我想,只要她在外面平平安安,就算从我们这个案子中解脱出来了。

我觉得,林昭之所以能保外,与当时的政治大环境也有关,并非对林昭特别照顾。主要是七千人大会以后,风向就有点转变。1962年1月11日到2月7日,中共中央在北京开了七千人大会,我们在监房读报时得知了这些消息,否则是不可能放她出去的。另外她母亲在上海,可能也有一些活动,她是苏州市的政协委员,是一个有影响的人物。

我们在里面一年多,这个案子审来审去,应该也弄清楚了。刚开始审讯时,那些人很凶的,后来我看到有点变化,他们显得比较客气了。

还有,林昭给我的那些信,也确实证明她没有参与我们的活动,她也不知详情,所以就先把她放出去了。

1962年形势的变化,让我也得到一些特殊优待。就是在林昭放出去的那段时间,有一天,一位干部医生突然来到我监房门前,她叫我站起来,对我说:”看你脸色不好嘛。”我心说,把我关了那么久,饭也吃不饱,好久都不能晒太阳,脸色怎么可能好嘛。没有镜子,自己也知道的。

其实,要不要把你当病号,都是上边一句话。不久,没有做任何身体检查,我就被调到二楼病号监去了。本来监房都是三个人、四个人一间,乱七八糟挤在一起,而二楼的病号监是一人住一间。

这样我在病号监里住了一个多月,吃病号饭,条件稍微好一点。

说到吃饭,我刚进二所的时候,早晚都是吃稀饭。送过来时是放在一个铝制的格子里,一个人只给一格子稀饭。我们叫它四眼粥,看上去稀饭里面也有两个眼睛,就稀薄到这个样子,稍微有点酱菜给你。

中午吃山芋,蒸红薯,那就给得比较多了,有一二斤,满满的,管饱。后来中午改成米饭,很小的铝格子,也有点菜,一点点,不够吃。

在二所可以得到家里接济了,每个月能送进来十个鸡蛋。我叫家里送鹅蛋,比鸭蛋大一点。后来家里买不到鸡蛋,就在亭子间里养鸡。关在二所的那几年,妹妹每个月给我送进来十个蛋。

1962年10月1日,国庆节,那时我刚好在病号监,可以开大账。大账就是你进去的时候,身上的钱可以存在那边,家属也可以为你存一点钱,那就可以买一点生活用品。那次过节,劳役犯,就是送饭的人告诉我说,你可以买一斤猪头肉、半斤糖果,其他犯人没有的。他说,对你是特殊待遇,跟干部一样。他们干部过节,也只有这两样东西。我很久都没有吃过肉了,一斤猪头肉,没几天我就吃光了,半斤糖果吃的时间久一点。

还有一件很重要的事,就是分案审理。把《星火》案中我们三个人从甘肃天水那边分离出来,交给上海审理,在上海判,而不是交给甘肃判。检察院的院长亲自来提审时跟我讲,他们打官司打赢了。我那时还不理解,他说:“你放心,现在已经定下来了,你的案件我们管。甘肃那边要求并案,把两个案件并为一个案子,我们不同意。”他知道,我在1959年底就离开了天水,林昭在上海,梁炎武先后在北京和广州,与张春元在天水那边搞的事情并没有关系。所以他们坚持不让并案。我想,这样重要的事情,他居然告诉我。

如果交给天水那边审判,估计我们的遭遇会差很多,后来平反的阻力也更大。而留在上海,分别立案,那么审理、判刑,送到市监狱,还有档案怎么写,权力都在上海的机关手里。检察院的院长还说:“你好好表现,会对你从宽处理。”

我对二所的管理人员,印象要好一点。他们对犯人,在人格上还是尊重的。原因在哪里呢?据说那个监狱长是地下党的工作人员,解放前就在监狱里管犯人。他对国民党的管理是看不惯的,解放后他当了头头,很神气的一个人。犯人们传说,他是前国民党监狱的留用人员,其实不是。那时共产党渗透到很多关键地方,监狱里也有他们的人在。那么一解放,就反过来由他来负责主管了。二所也有一部分是留用人员,可能原来也是帮过共产党的。监狱长就是那位老资格的地下党员,他对这里最熟悉。1961年上海的粮食供应还是很紧张,而他对犯人的口粮还是保证了的。林昭第二次被捕后,被关押在第一看守所,那边就和二所完全不一样了。从林昭写下的文字来看,她在一所受到了残酷的迫害。

二、林昭去了我家

在二所等到1965年5月31日,判决书出来了。我被判十七年,林昭刑期更长,判了二十年,梁炎武被判七年。直到这时我才知道,林昭又被关进来了。

我们三人应该是同时转到上海市监狱的,就在提篮桥这个地方,判决结束后,一辆车送我们过去。开庭时我没有见到林昭,转监狱时在车上我遇到梁炎武。时隔五年,我们俩第一次近距离见面了。

他和我都拿了行李,我的行李中,有家人给我带进来的外文书。我想,他家在外地,估计没有人给他送书,我就拿了两本外文的物理书给他。

进监狱时要拍照,拍好照以后,分到各个监房。梁炎武被分到六号监,我被分到一号监。他后来被发配到白茅岭服刑,刑期虽然比我少十年,刑满后也不能离场。一直到“文革”结束,冤案平反,他才回到北京与妻女团聚。他没能在北大物理系恢复教职,而是去了一所纺织学院任教。

判决后,家人就可以到提篮桥探监了。第一次探监是我母亲跟我妹妹两个人来的。那天来了很多人,至少有十多个窗口,全部是装好了铁栅栏的。母亲和妹妹把一些接济我的东西交给看守人员,由他们转交给我。我们可以交谈,但每一个犯人都被盯住的。顾麋比较灵活,她胆子大。她居然说:“林昭到我们家来找过的!”

我想旁边有一个人看着的,你敢说......她跟我讲了,我不敢回应。旁边监视我们的人,可能不知道林昭是谁。但我心里有点紧张,因为这是第一次接见,那人就在旁边,你讲什么东西他都听见的。

这样我才知道,林昭到家里去过了。我被关了五年,没有和亲人见过面,这是第一次,回来监室后我哭了。

我母亲心里也是很难过的,我妹妹年纪轻,还不满二十八岁,她无所谓。她说林昭来过好几次,这样我才知道林昭对我的态度。她并没有因为我牵连了她而回避我和她的关系,更没有为了保住这份失而复得的自由,而约束自己那任性的独特性格。

结果,问题就来了。1962年3月5日保外就医时的林昭,和之前与我们的政治活动保持距离的林昭完全不一样了,和《思想历程》里的林昭相比,简直可以说有一百八十度的转变。保外后她不仅没有安稳下来,而且行动更激进了。她后来的情况我在狱中不可能得知,都是我在刑满后探亲以及1980年平反以后逐步了解到的,所以我现在有以下的分析:首先,她在得知保外时,没料想到,所有同案犯中,我们都还被关押在里面,单独把她释放了。她将此举看作对她人格的巨大侮辱,因而坚决拒绝出狱,她妹妹讲过当时的情形。

【彭令范曾接受记者张敏采访——“她就是讲:‘他们放了我,就又要把我抓起来,用不着这样麻烦。’所以她拉住桌子的角,我跟我母亲接她出来,她不肯出来,里边的人也没有办法,僵在那里。后来,分局的人就对我母亲讲:‘你想办法把她带走就算了。’后来我母亲就打电话给她朋友,他们家有一个花匠,来把她带上三轮车,送回去。”】

林昭出来后,经常到我家去,还给北大校长陆平写信,要他站出来为学生说话。她母亲知道了,觉得这个事情不对头,还是要她回苏州去,避开上海这个案发地。结果,她在那里认识了朱红、黄政,搞了一个组织,还有纲领。这个人性格就是这样,你越是禁止,她越要搞,另起炉灶,她就走这条路了。

我看《思想历程》时认为,第一次被捕,她心里是怨我的,是我把她拖进来了。但把她放出去后,她倒过来认为她有亏欠了:你们会认为我写了那个思想检查,跟你们划清界限,就把我放出来了。肯定是我交代了什么东西,才得到了宽大。她要证明,不是的!所以她第一步要到我家里去解释清楚:我没有出卖顾雁。她一定要把这个事情跟我家里讲清楚,我推测她是这样一个心情。

所以她也跟我妹妹讲,她拿了个包裹,到静安分局去静坐,要求把她抓回去。那意思就是,你们当初抓是不应该抓我,但是你们放也不应该放我——要放就全部放。不是我无罪,大家都无罪。既然你们不放他们,也不应该放我。

我认为这时她意识到,在《思想历程》里写得有点过分了,不应该把我们做的事情说得毫无意义。现在好了,她因此就被保外了,这对她的道德良知是一个侮辱。

你说人不会因为个人意气押上自己的性命,这不是个人意气呀,她这样做有她自己独立的政治信仰。而人的信仰是有道德支撑的,我不是跟你讲过,战国时代有“齐大饥”的故事:

齐大饥。黔敖为食于路,以待饿者而食之。有饿者,蒙袂辑屦,贸贸然而来。黔敖左奉食,右执饮,曰:“嗟!来食!”扬其目而视之,曰:“予惟不食嗟来之食,以至于斯也!”从而谢焉,终不食而死。曾子闻之,曰:“微与!其嗟也可去,其谢也可食。”《礼记·檀弓下》。

这个人,人家讲了他一句,嗟!来食!他就火得不得了呀。我宁可饿死,也不吃嗟来之食。林昭就是这样,道德上的清白比什么都重要,这在她人生中是第一位的,不能有一点污点。所以她出来第一步到我家,就是要表明这个态度:把我放出来,顾雁没有放出来,不是因为我写检讨,跟他们划清了界限。我是想在里边的,我不愿意一个人被放出来。

倪竞雄也跟我讲过,她说林昭释放后去找她,看上去有很大的变化,完全变掉了。林昭从她母亲那里,肯定知道张春元在1961年越狱后,也是从甘肃到苏州,一路找过来。他到上海我家里去找我,又到苏州去找她。林昭出来以后,她也是同样如此,她要找到我们其他人的下落。结果得知,只把她放出去了,我还关在里边,其他人也都关在里边——这是她不能接受的。

三、顾麋:那时林昭经常来

以下是顾麋的回忆:

那是1962年早春,林昭放出来后,一天下午,她一个人来到我家。那时我们住在552弄23号,那个地方底层已经被改造成公共食堂。很多人在食堂吃饭,出出进进,她来就比较方便,并不引人注意。

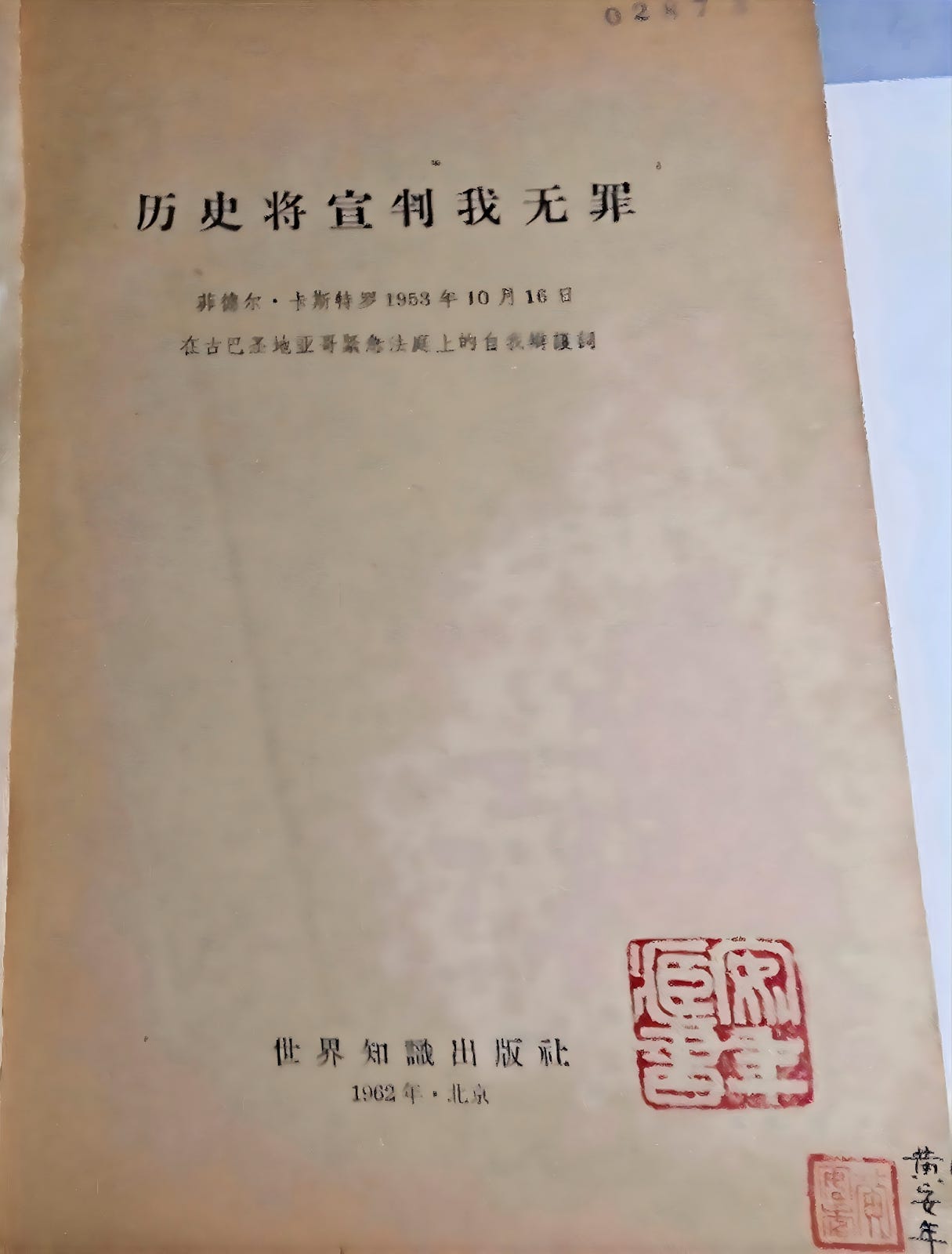

到了夏天,我父母到乡下去住。那一段时间,就我和大哥在家。林昭经常来,来了就滔滔不绝地和我大哥讲话。所以我大哥受了林昭的影响,1965年5月底他们这个案子宣判后,我大哥匿名给静安区法院的法官寄去了这本书——菲德尔·卡斯特罗《历史将宣判我无罪》。

林昭把她写给北京大学校长陆平的信,还有她写的诗歌给我。我又给我爸看,她喜欢写现代诗。在我们家,她无话不谈,有时就一个人,自管自讲话,她也不要你回答。她讲安徽吃不饱,饿死人,她好像都知道的。我就写在日记本上,结果,“文革”抄家被抄去日记,这是我很重要的一条罪行。

她一次又一次来我们家,倒是没有人来问过。后来是小哥(指顾雁)说的,当然没有人来问,因为警方有意让她出来,还要看她和什么人联系,看有什么人逍遥法外,没有落网。他们要找到那个幕后不出来的人,特别是那个叫“大哥”的人。

四、伏脱冷·鲁凡·大哥

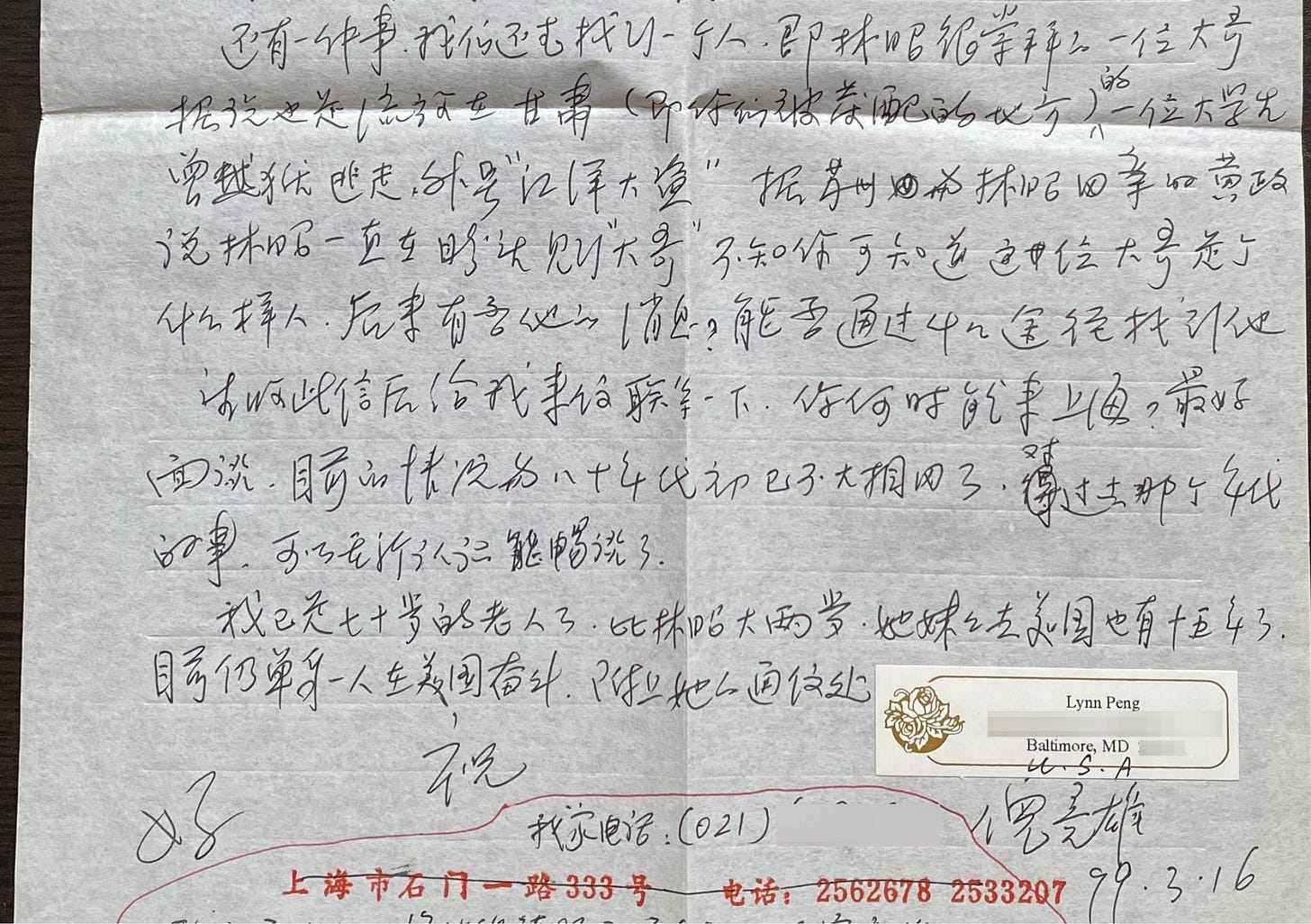

艾晓明:“大哥”是谁呢?37年以后,1999年3月16日,林昭的同学和闺蜜倪竞雄给顾雁写信,询问这位“大哥”的下落——

倪竞雄:“还有一件事,我们还想找到一个人,即林昭很崇拜的一位大哥,据说也是流放在甘肃(即你们被发配的地方)的一位大学生,曾越狱逃走,外号‘江洋大盗’。据苏州与林昭同案的黄政说林昭一直在盼望见到‘大哥’,不知你可知道这位大哥是个什么样的人,后来有否他的消息?能否通过什么途径找到他。”

顾雁:审讯我的时候,他们问:“‘大哥’是谁?”我说:“‘大哥’就是张春元啊。”林昭在和我在通信中,不提张春元的名字,而是用“大哥”来替代,例如问“大哥情况怎么样”。除了林昭以外,我们中间没有一个人称呼张春元为“大哥”的。

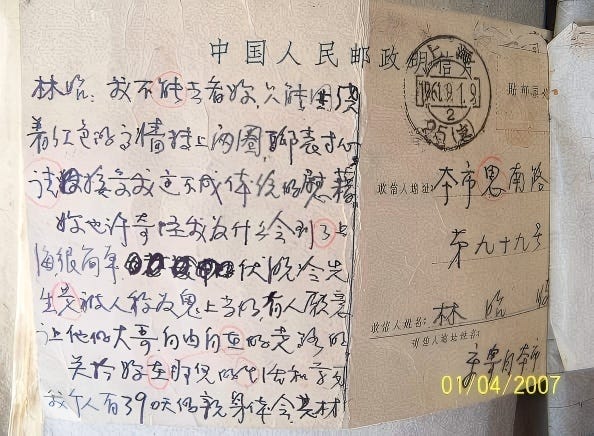

【艾晓明注:1961年8月10日,张春元逃出监狱,此后一路流浪跋涉,从兰州至上海,上海至苏州。他在苏州见到林昭的母亲,得知林昭被捕的情况,又返回上海,并给林昭寄出一张明信片。林昭肯定没有收到这张明信片,二所截留了它,后来转到天水张春元的案卷里了。四十六年后,谭蝉雪在天水寻找张春元案卷时,找到了这张明信片,并作为《星火》一书的插图——

根据右上方的邮戳可以看出,明信片是1961年9月1日从上海寄出,收件人地址为“本市思南路第九十九号”,即第二看守所的地址,因为明信片装订在案卷中,右边图文不完整。信文写在左边,谭蝉雪引用了这样几段:

“林昭:我不能去看你,只能围绕着红色的高墙转上两圈,聊表寸心,请接受我这不成体统的慰藉。”

她引用的另一段文字,应该是写在这张明信片的反面:

“我们的生活,其材料之丰富、多趣是能写一本书的,而且是古今中外所没有的。愿你能抱着‘既来之则安之’,自己一点也不着急的态度,很好地读完这本有用的、难得的书,将来为人民更好地服务......我们光明磊落,心胸坦然,敢于斗争,只有敢于斗争的人才能敢于胜利。”

明信片插图左边中间还有六行字,谭蝉雪没有引用,但十分重要,我这里补充录入:

“你也许奇怪,我为什么会到了上海,很简单,伏脱冷先生是被人称为鬼上当的,有人愿意让他的大哥自由自在的走路的。关于你在那儿的生活和学习,我个人有390天的亲身体会,其材”(图左文字完)。

谭蝉雪在《星火》中写道,张春元以林昭母亲的名义给林昭写了一封信。但如果考虑到“伏脱冷”“鬼上当”的提示,就能明白,这与母亲的口吻不符。伏脱冷是巴尔扎克小说《高老头》中的一个人物形象,身为逃犯,诡计多端。张春元相信,林昭看到这里,当明白“大哥”他已越狱成功。此外,这张明信片正面右边,在通讯人地址姓名那一栏,第一个字是个连笔字,看上去像简体字母亲的“亲”,实际是更近于草体的“章”。张春元在《电影文学》1959年6月号上发表的剧本《中朝儿女》,笔名正是“司马章”。如果林昭真能收到此明信片,定能意会寄信者谁。】

顾雁:张春元到西康路我们家来过的,第一次是他和谭蝉雪两个人从河南过来,我从黑桥过去把他们接到乡下去住,所以他和谭蝉雪都知道我在上海西康路的住址。

顾麋:张春元,我是看着他从弄堂里走进来的。那时我正好在窗口搞卫生还是干嘛,时间应该是中午,下面在食堂吃饭的人很多。他上来时,没有人注意。

那时我和妈妈住在大房间,这是正房,向南的;北边是小房间,亭子间,我爸一个人睡在那里。张春元直接走到亭子间,他好像知道一样,这个我印象很深。

我爸在亭子间里,隔了五分钟还是十分钟左右,我爸进来找我,他说:张春元来了,给他全国粮票。

我们没有请他吃饭,我爸肯定告诉他了,小哥被抓,家里被抄过。我看着他走的,他也不到大房间来跟我打招呼。应该是他有意回避了,不要跟我有直接的接触。

他走的时候,我就在房间的窗口看他,他一直往前走,头也不回。快到弄堂口了,他头回过来,看一看。然后再转过去,走得也不快。

后来爸爸就过来,他跟我说:“张春元监狱里逃出来。”

他走了以后,事情多了。有两个人来,拿了张春元的照片,问我妈:“你认识这个人吗?”

这两个人哪里来的,我也不知道,我在上班,没碰到。我妈那天并没有见到张春元,她肯定说不知道是谁。

弄堂里的邻居跟我妈说:“你们家里来了个什么人?警察要我们看照片。”但是看也看不清楚,没法辨认。因为弄堂里那么多人,食堂里人来人往,他走出去,人家当他是来吃饭的,谁会注意?没人注意。

他穿了一件深色的中山装,走的时候好像是秋天。

顾雁:静安分局一直认为,为林昭的诗《海鸥》写《跋》的鲁凡,是一个老手。《跋》那里注明的时间不是1949年以前吗,那这个人到底是谁,他们非要找出来。

我说这个鲁凡没有的,是化名。是谁的化名?我说是我的,我写的《跋》。我为什么这样说?这是我给他们摆的一道。第一我要跟张春元通信息,告诉他,我也进来了。因为我的口供,公安肯定要去找他对质的嘛,一对他就知道我的处境了。还有就是讲义气吧,不要认为我顾雁会叛变他,我顾雁是怎么样一个人你也清楚的。他可能是想不到的,我一口咬定,那个《跋》是我写的。张春元可能会这样想,顾雁还是有一手的。谭蝉雪在《星火》那本书里写道:“张春元和顾雁分头执笔写跋,最后采用了顾雁所写的,但顾雁本人已记不清了,至今他还认为是张春元写的‘跋’,他只记得为什么用了‘鲁凡’笔名,寓意是鲁迅走了。”我怎么会不记得呢?我就是有意这么做的。张春元肯定承认《跋》是他写的,而承办员找他对质时,他就会明白我在有意说谎,于是他又随口编了一个故事,说是我们两个人分头执笔写《跋》。天水当局被糊弄过去了,但静安分局感到此事有蹊跷。他们觉得有一个可能——我和张两人都在说谎,意在包庇这个叫“鲁凡”的人。而谭蝉雪在《星火》那本书里写我和张春元“分头执笔”,我认为是在案卷里看到了我的口供,但她没有把这些案卷资料给我。

张春元那次逃跑,如果是为了逃生,那就跑错路了。他不应该往南跑,如果往西北跑,逃到少数民族地区,他谋生的能力强得很。在那些地方,户口管理也不像上海这么严密。但他逃到这边来,他是想找到我们,而我们全部都被抓了啊!

胡杰纪录片里讲,把林昭放出来,是要找到张春元;其实不是的。1962年3月林昭被放出来时,张春元已经在1961年9月6日归案了。放林昭,一个方面是我前面说的,形势有所松动。另一方面,也是要看她出来后与哪些人联系。他们不是要抓什么小人物,而是要找大人物,例如,那个“鲁凡”究竟是谁。那么第二次抓了林昭以后,到1963年夏天还放了一个张茹一出来,让她以林昭同监室狱友的名义,联系我妹妹,又去了苏州,继续找“大哥”。这些都说明,他们不相信我讲的话,以为“大哥”是另外的人,此人不是张春元,他还在外边活动。

五、张茹一来找“大哥”

顾麋:张春元走了以后,过了一段时间,张茹一来了。她一来就问我,大哥现在情况怎么样?

张茹一长得什么样子?六十多年前的事情,记不得了。我也不知道她是为什么被抓的。她家在上海边远郊区,自己讲上海话的。她的家我知道,那边全是农村。她的妈妈还在,她爸已经不在了,估计是有什么问题。她本人那时还很年轻,好像二十岁不到,大概十八九岁的样子,梳了两根辫子,一看就像个中学生。她跟我说,是林昭叫她来的,而且还带了林昭的亲笔信。

林昭写的是什么,我也不记得了。总之张茹一说,她跟林昭关在一个监狱里。她谈了林昭的一些情况,我觉得不像是编造出来的。也可能静安分局有意把她们安排在一起,都在提篮桥市监狱。

【艾晓明注:林昭第二次被捕是1962年11月8日,到12月23日,她被关进提篮桥市监狱,在那里羁押八个半月。市监狱原本是关押已决犯的,但把未决犯林昭关进去,可能是一个别有用意的处理。与林昭同监室的一个犯人,名叫张茹一,在对林昭的起诉书上,张茹一被称为“诈骗犯”,但林昭在对起诉书的批注里说张茹一是政治犯。1963年7月,张茹一被释放的同时,接受了公安布置的特殊任务,她先到了顾雁在上海的家,然后又去了苏州,找到了林昭的朋友朱红和黄政。】

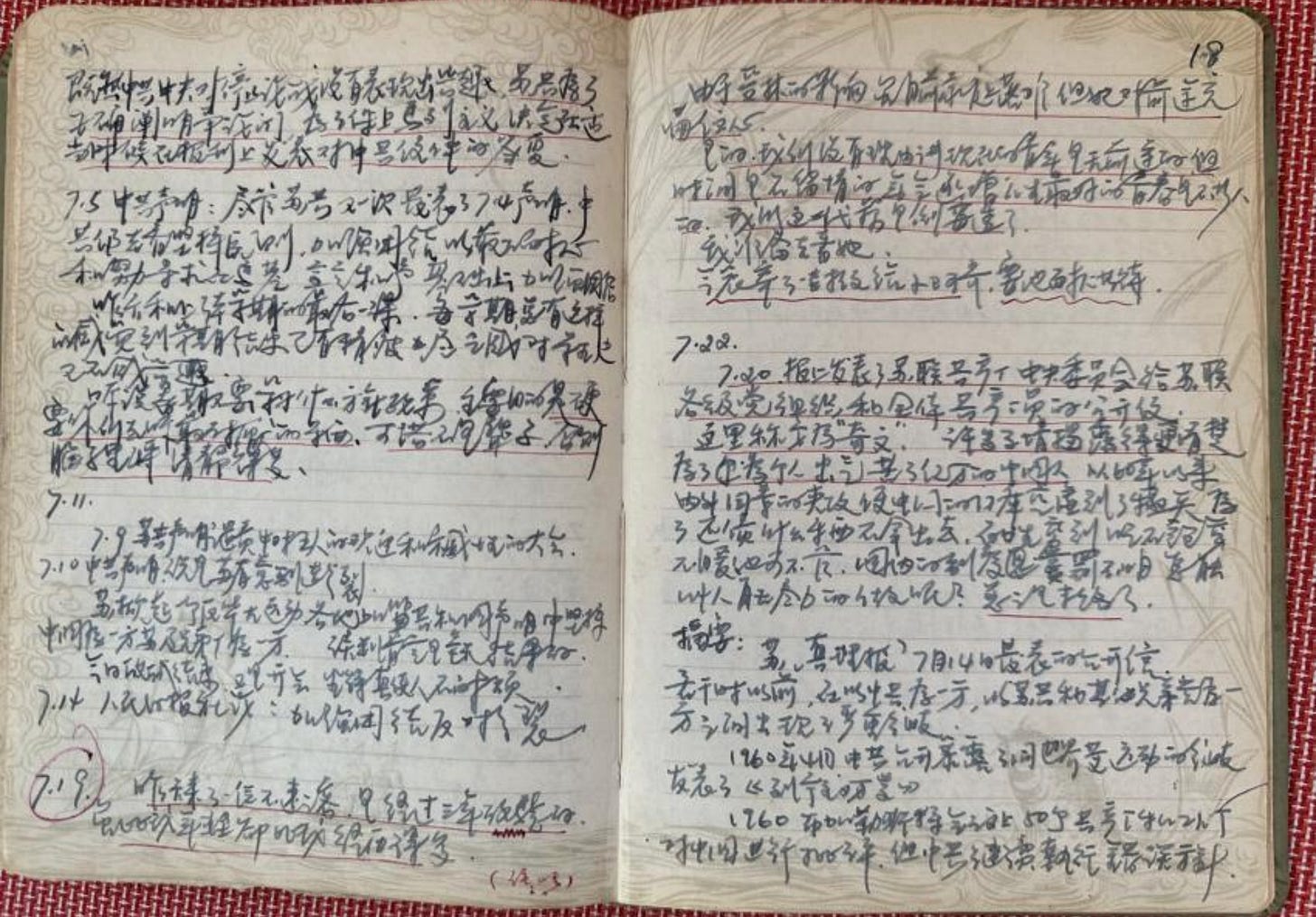

顾麋在日记中记录了这日张茹一来访:

上图左页倒数第二行开始,到右页第七行,文字如下:

1963年7月19日

昨天来了一位不速之客,是经过三年考验的,虽比我年轻却比我经历得多。

由于受林的影响,虽目前家庭落难,但她对前途充满信心。

是的,我们没有理由讲现在的青年是无前途的,但时间是不留情的,年龄逐增,人生最好的青春是不等人的。我们这一代算是倒霉透了。

我准备去看她。今晨寄了一封信给小阿哥,要他耐心等待。

顾麋:张茹一约我到复兴公园,每一次,她一定要问大哥。我说,我哥现在在上班,蛮好啊。

这个时候,我并不知道她是监狱里派来的,我相信她是和林昭一起的,先放出来了。因为林昭的关系,我还是蛮关照她的,她要借钱,借书,我都同意了。

【顾麋1963年8月30日的日记中提到:“她上星期借去8元,拿了几件衬衫,使得我们的经济,窘得连票子的钱也无法对付。”】

张茹一住的地方好像是在宝山,有一次她跟我说,到她老家去玩,说她那边还有一些同伴。听她讲的情况,不像是骗人。

不久,我大哥顾鸿跟我说,不要再睬她了,离她远一点。而且,顾鸿从来没有跟她讲过一句话,她来就盯上我,叫我到哪里碰面。每次翻来覆去就是问大哥,后来我光火了,我讲:“你说大哥,我们只有一个大哥,我们不叫大哥,叫阿哥。你老是大哥大哥,到底是啥人啊?没有这个人啊!”

她从此就不来了。

大哥到底是谁?这个谜底后来揭晓了。我妈有一次收拾东西,从五斗橱里翻出来一个空盒子。我妈跟我说,这个盒子是林昭留下的,你看一看,不要扔掉。这个时候已经好几年过去了,是六七年还是六八年,林昭已经抓进去了。反正,我妈给我看,一个放苏州豆腐干的盒子。我讲,你放个空盒子干啥,拆开来看看。结果我妈把盒子盖掀开,什么也看不见。底板上有一张纸,掀开拿起来那底上的一张纸,下面有几个字,抬头写的就是“大哥”。这句话写得是什么,那我倒不记得了。很简单的一句话,下面是不是林昭的名字,我也不记得了。为什么记得这个“大哥”,因为张茹一一天到晚就在问“大哥”。我恍然大悟,她要找的,就是这个大哥。张春元。你们是叫大哥的对吧?这个盒子,可能是林昭让我们家保存的,里面她给张春元留了这个短信。

在张茹一之后,接下来,又来了一个男的。他说是跟顾雁在监狱里一个监房的,对顾雁的情况了如指掌。这个人三十出头,不像青年人。一来,正好我们的亭子间空着。他说要住到我们家里来,说我给你们五十元一个月。那个时候,我们工资也不过五十左右,这笔数很大的。我爸有点犹豫,我说不行。我说:你住到哪里去?我们只有两个房间,我就没有同意。

他看样子,就好像要跟我谈朋友一样。我睬也不睬他,跟他没话讲。为什么呢?因为后来,他跟我父亲说,他在江湾的医院里面,要我去看他,一定要去一次。这桩事让我很反感,我父母倒没有勉强我。也许他给了我父母什么好处?好像也没有。总之这个人坚决地说,要我到江湾去一次,最终我没有去。

那时我们在亭子间里面原来放床的地方,养了几只鸡。那时买不到鸡蛋,我们养鸡,为了吃鸡蛋,还要给顾雁送鸡蛋。我在窗台这里切菜皮,准备给鸡吃,这个人就坐在我台子对面,我不管他,乒乒乓乓切菜。他也不走,那边就是五六只鸡,还有一只鸭子。他好像来过两趟,他说是跟顾雁一起的,他这样跟我们讲。

顾雁:我对这个人有印象。刚抓进去的时候,每人一个角落坐好。到了一定的时候可以起来,排好队在监房里转一圈,他就跟在我后面。记得他突然跟我讲,他说他是部队里的,是彭德怀的部下......我一听就很警觉。这么大年纪了,专门来找我,肯定是公安局派来的嘛。我就不睬他,两次以后,他不来了。

顾麋:你怎么晓得啊?

顾雁:监房里形形色色的人都有,我当然晓得啊,估计还就是这个人。那段时间,还有一个小青年,十五六岁的,他说想逃香港被抓了,这样的人讲话我还是相信的。那个人说是部队里面彭德怀的部下,我一听就知道,这个人来路不明。年纪这么大了,我那时候还是个小青年呢。

每次可以站起来走一圈的时候,他就跟在我后面。后来就不见了,因为进进出出人很多的。

六、分别起诉,同案宣判

【彭令范:“因为主要的犯人只有判七年,林昭判得最重,所以我母亲呢,总是觉得,她的那些右派朋友不像她这么跟共产党斗争,或者呢,有的地方什么事都推在她身上。因为有一阵子,我母亲有好多写给监狱长的信,不晓得是几百,千封也有了。”】

在我、林昭、梁炎武三人的判决书上,林昭确实是判得最重的。我是第一被告,被判十七年。林昭是第二被告,被判二十年。梁炎武是第三被告,被判七年。请注意,这张判决书的编号是“1962年静刑字第一七一号”,它与我手里的起诉书同年(1962年8月1日),但当年没有判决,而是拖了近三年,到1965年5月31日才发出。这是为什么呢?

这中间,我和梁炎武一直是被羁押状态,只有林昭在1960年3月5日至11月8日保外就医。那么,判决拖了这么久,就是静安分局要扩大战果,继续布网。他们认为破案计划未完成,即使张春元归案了,那个“鲁凡”究竟是谁,他是不是“大哥”,他们要继续找。所以张茹一来找顾麋,有那个人自称是“彭德怀的部下”去我家租房。张茹一又到苏州去找朱红、黄政,结果导致黄政被判了十五年。

林昭保外期间在苏州的活动,我当时不可能了解。而在我自己的口供里,不存在把事情推在林昭身上的情况。我这篇文章一直坚持的就是:林昭没有直接参与《星火》的活动,她最多可以说是我们思想上的同道。至于梁炎武,他所干的具体事很少,只是为谭蝉雪、张春元传了信。他与林昭没有见过面,也不可能把事情推给林昭。

对我们三人的判决,林昭的刑期最重,主要是她在保外就医这段时间的经历。另外还有一张起诉书,我和梁炎武不在其中,是1964年11月4日单独针对林昭的起诉。

林昭抄写了这份起诉书,林昭平反后,这份手稿和林昭的其它手稿一起退还给彭令范了,现在网上可以查到。林昭在抄写时,字里行间以括号加注,写了很多反驳。

这份起诉书,编号依然是423号,林昭被称为“中国自由青年战斗联盟”反革命集团的主犯。

到1965年5月底的判决书中,林昭又被归入到我和梁炎武三人案里。其中,1960年的《星火》案、1962年林昭保外期间的活动,特别是林昭第二次被捕已经八个月后,由张茹一联络参与在苏州发生的事情,全部都归到了这一个“反革命集团”案中。我、林昭、梁炎武都羁押在上海,我们三人作为同案,同时宣判。

为查寻林昭的经历,倪竞雄找过张茹一,没有找到。我和顾麋的“反革命”案平反以后,张茹一主动打电话给顾麋,她向我妹妹道歉,承认自己在公安那里领了任务。公安承诺给她安排工作,但并没有兑现。张茹一后来去了新疆,也苦得很。文革后她也回到了上海,就住在浦东。我不知道她到底是平反了还是没有平反。

她不敢到家里来,她跟顾麋说:“现在他们都来找我,我也是受骗的。”

七、“纪念夏瑜”

和林昭同在市监狱,我被调进翻译组,算是一种特殊待遇吧。和大多数人一样,我抱着逆来顺受的想法。不同的是,从二所到提篮桥,我一直在阅读和思考数学、物理问题,这是我的精神寄托,也让我与现实的痛苦相对隔绝。可以说,我的处境比很多人幸运。

我见不到林昭,只是知道她被当作“反改造”的典型。吴明卫问过我:“有没有想到过劝她?”那怎么可能呢?完全不可能接触,狱方也不会让你接触。

1967年7月,我和一批大刑犯人被遣送青海西宁,安排在青沪机械厂服刑。

大概是1969年1月或2月,我得知林昭遇难的消息。当时是上海派人来提审我,那个提审员问我:“林昭已经被枪毙了,你知道吗?”我此后写信告诉了父亲,但我不能直说,所以暗示道:“林昭走上了夏瑜的道路。”我想那些管理员知道秋瑾,不见得知道鲁迅笔下的夏瑜。我父亲一看就清楚了。

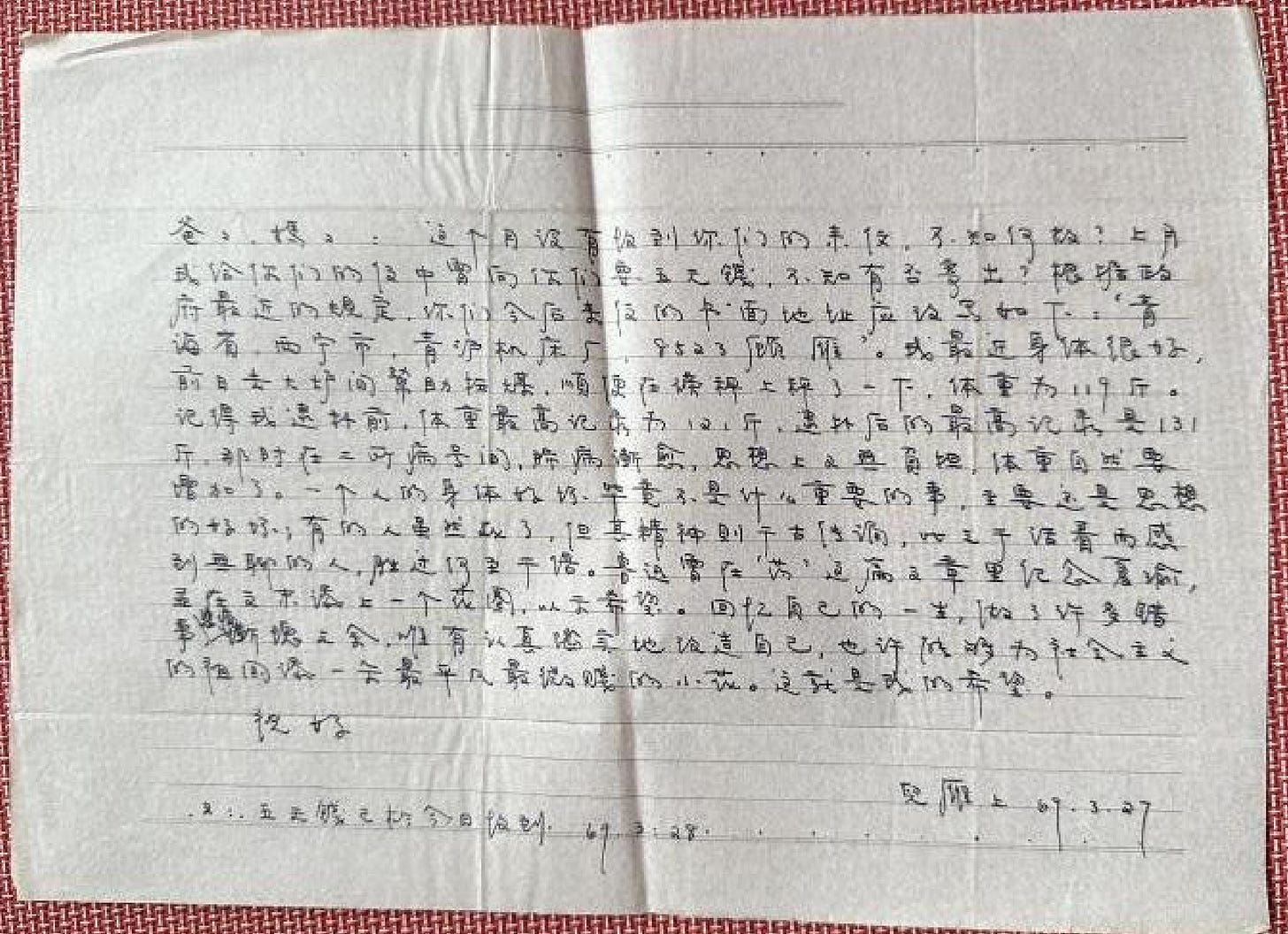

我母亲保留了我的青海来信,她装订得整整齐齐。后来我在上海家中看到母亲装订的家信,其中有我在当年3月份写的信:

爸爸、妈妈:这个月没有收到你们的来信,不知何故?上月我给你们的信中曾向你们要五元钱,不知有否寄出?根据政府最近的规定,你们今后来信的书面地址应改写如下:“青海省、西宁市、青沪机床厂,8523顾雁”。我最近身体很好,前日去大炉间帮助拉煤,顺便在磅秤上秤了一下,体重为119斤。记得我逮捕前,体重最高记录为121斤,逮捕后的最高记录是131斤。那时在二所病号间,肺病渐愈,思想上又无负担,体重自然要增加了。一个人的身体好坏,毕竟不是什么重要的事,主要还是思想的好坏;有的人虽然死了,但其精神则千古传诵,比之于或者而感到无聊的人,胜过何至千倍。鲁迅曾在《药》这篇文章里纪念夏瑜,并在文末添上一个花圈,以示希望。回忆自己的一生,做了许多错事,悲痛惭愧之余,唯有认真踏实地改造自己,也许能够为社会主义的祖国添一朵最平凡最微贱的小花。这就是我的希望。

祝好

儿 雁上

69.3.27

我不能直叙胸臆,只能这样曲笔暗示。终是意难平,忍不住在“惭愧”二字前面,又添加了“悲痛”二字。

我父亲一看就清楚了,他已有一年五个月没有给我写信。接到我的信后,连续两个月都是他给我写信。

父亲能说什么呢?“文革”期间,大哥顾鸿因为给法官寄《历史将宣判我无罪》那本书的事,被当作“漏网反革命”轮番批斗,还追查他跟张茹一说了什么。在巨大压力下他非常绝望,自杀未遂。妹妹顾麋的日记被查抄后,她被送进虹口分局看守所,戴上“现行反革命”帽子......(顾麋的“日记罪”,后面专文再写)。家里发生的事情,父亲不能告诉我,他只能用最流行的政治口号来勉励我,要我“纠正自己空虚和错误的思想”。

回复父亲的这封信时,我直接写出了林昭的死:“林昭的死并不能影响我的改造决心”。我的信要通过狱方审查,不能不用这种违心之语。我引用了秋瑾的诗,告诉父母,自己不会沉湎于悲痛中,以免除他们的担心:“记得前人曾留有‘秋风秋雨愁煞人’之句,这是历史人物在特定场合下的精神状态。现在时代不同了,如果在这种场合下也碰到天雨的话,我相信所想到的一定是雨后万物竞生的新春景象,因而充满了信心和希望”。

1969年5月8日,父亲回复我,套话之外,他鼓励我:“凡是进步的人,都是青春常在。我希望你坚持着改造的信心和勇气,千万不要灰心。”

父亲此后再未来信,这是我保留的他最后一封信,也是他留给我的最后一句话。

八、她提出的:我们去祭奠林昭

1974年,我因技术革新成绩而减刑三年,但刑满释放后仍然是强制留厂就业,只不过是从犯人圈子调换到就业人员的圈子。离开厂区还是要批准,与家人通信还是要检查。这时我明白了,不管你刑期多长,满刑与否,总之是没有自由,也不能离开劳改单位。一直到“文革”结束,形势才有了新的变化。到1978年底,关于彭德怀1959年的案子有了定论,我知道我们的案情多少与如何评价1959年的所谓“反右倾”相关,由此,我看到了平反的希望。妹妹在这年得到平反,我给母亲去信说,相信自己也会有这一天。1979年2月12日,我向上海市静安区法院提出申请,要求案件复查;同时也给兰州大学党委写了关于1958年被划右派的申诉材料。

当年3月2日,兰州大学发出了关于我的右派改正通知。我继续敦促法院复查,但几乎没有进展。我从其它渠道得知,主要是因为林昭的案子平反困难,其原因和经过,容后详述。

1979年6月22日,我在日记中记录了这一时期的心境:

“报上大力宣传的张志新的事迹刺痛了我的心,因为它使我想到了林昭,想到了我与她在选择人生之路上的分歧。每当在想象中出现林昭英勇就义的一幕时,我总隐隐地感到,如果我不能在今后的岁月里为人类作出一些贡献的话,那末我的活着将是可耻的。我能用什么方法来摆脱‘偷生者’这一不名誉的称呼呢?像《复活》里那位主人公一样,抛弃一切为挽救自己而努力吧!”

我不止一次地对来访的朋友说过,是我害了林昭。而我们之间选择的不同在于,我的抗争行动,到进监狱后就结束了。但她却从迈出监狱开始,一直到拼死抗争,献出生命。

1980年5月17日,上海市静安区人民法院终于做出决定,对我们的案子撤销原判。这一编号为(80)静刑复字012号的判决书中写明:

“至于他们二人当时由于对党和政府的路线、政策方面某些错误有意见,用议论和写文章向上反映情况的行为,是正确的。原判以反革命定罪判刑,显属不当,属于错案,应予纠正。”

法院宣告我和梁炎武无罪,予以平反。只不过,当初一起被起诉和判重刑的还有林昭,而留在这张判决书上的,只有我们两个人的名字了。

林昭案子经过复查,在三个月以后,即1980年8月22日,由上海市高院宣判无罪,但原因是说因林昭反右后就受到刺激,患有精神病,被错判后精神病复发,而不应将发病期间行为当作反革命而处以极刑。

在1980年10月30日给母亲的信里,我写到对这个判决的看法:

“梁炎武来信说北大纪律检查委员会找他去谈话,说北大要给林昭开追悼会,问他的意见,另外也问他对林昭平反判词的意见。梁的答复是说林60年就有精神病不合事实。我觉得这次林昭平反,阻力是在上海市高级法院。目前这个判决只是一个暂时的折中方案,因为大家心里都明白林并无精神病。现在不知北大的追悼会究竟怎么开法。”

由于彭令范的申诉及各界努力,林昭案在1981年12月30日得到再审判决,这个判决纠正了前一个判决的错误说法,宣告林昭无罪,彻底平反。

我自己平反后,找过林昭的弟弟和妹妹,她弟弟还住在茂名南路的房子里,妹妹在医院的宿舍住。我和彭恩华的来往多一些。他当时在学法文,我送给他了两大本法文字典。到苏州,办林昭和她母亲的葬礼,送花圈,都是通过彭恩华来联系的。我、同时也代梁炎武,一起表达了我们的哀思。

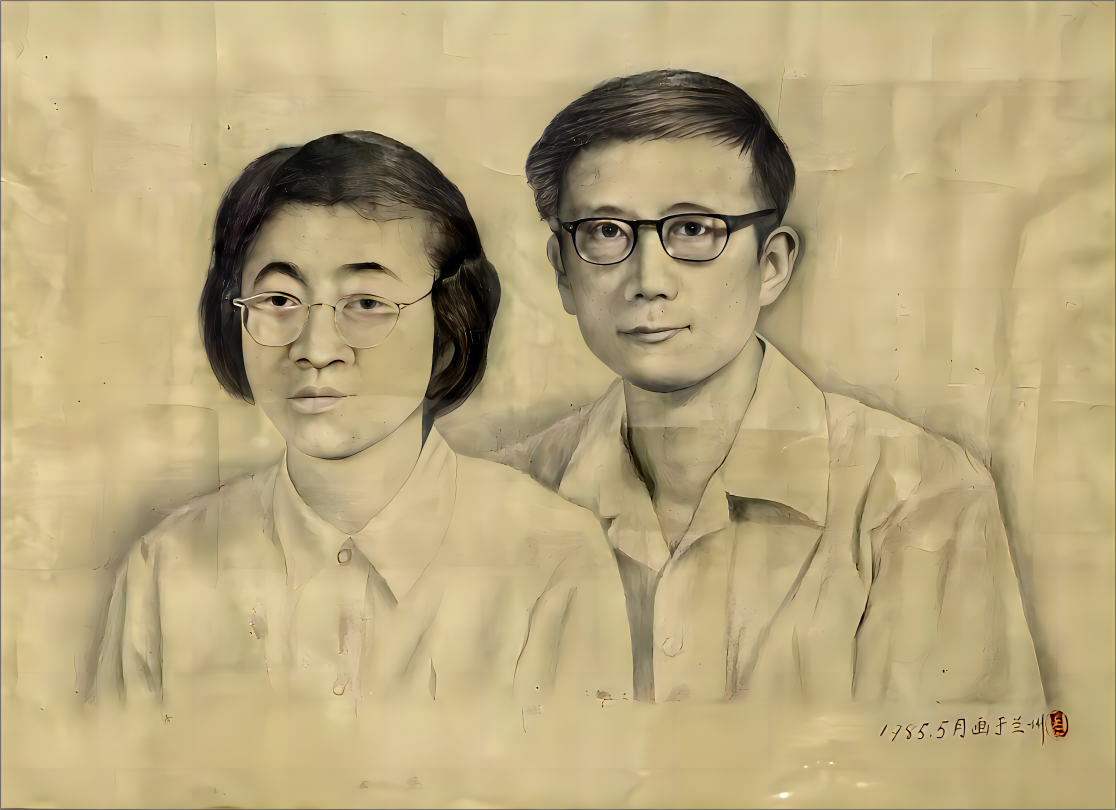

1980年7月,离开兰州大学二十二年之后,我回到兰大物理系任教,从助教做起。因为师母的介绍,1981年7月,我与力学系的讲师顾淑贤结为伉俪。结婚之前,我给她看了我的平反判决书,还有陈伟斯在1981年3月发表在《民主与法治》上的那篇纪念林昭的文章。

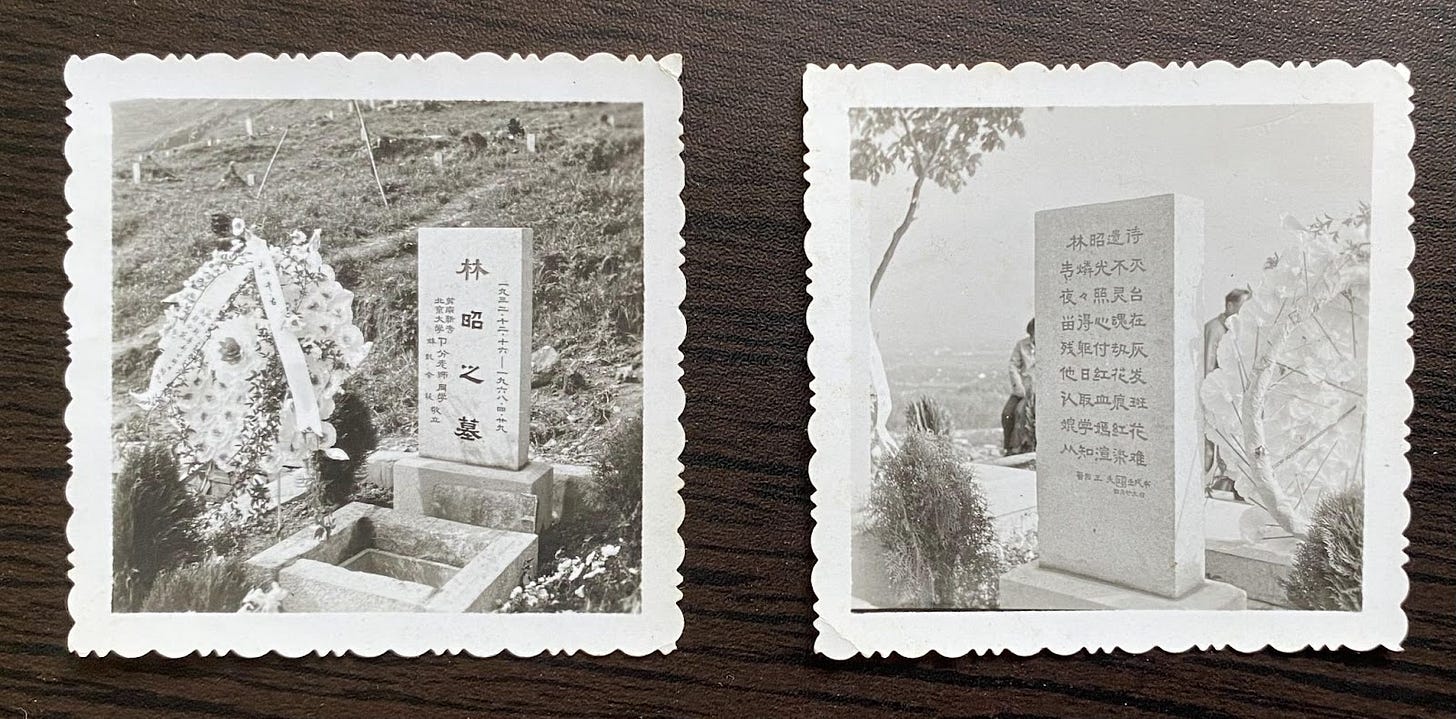

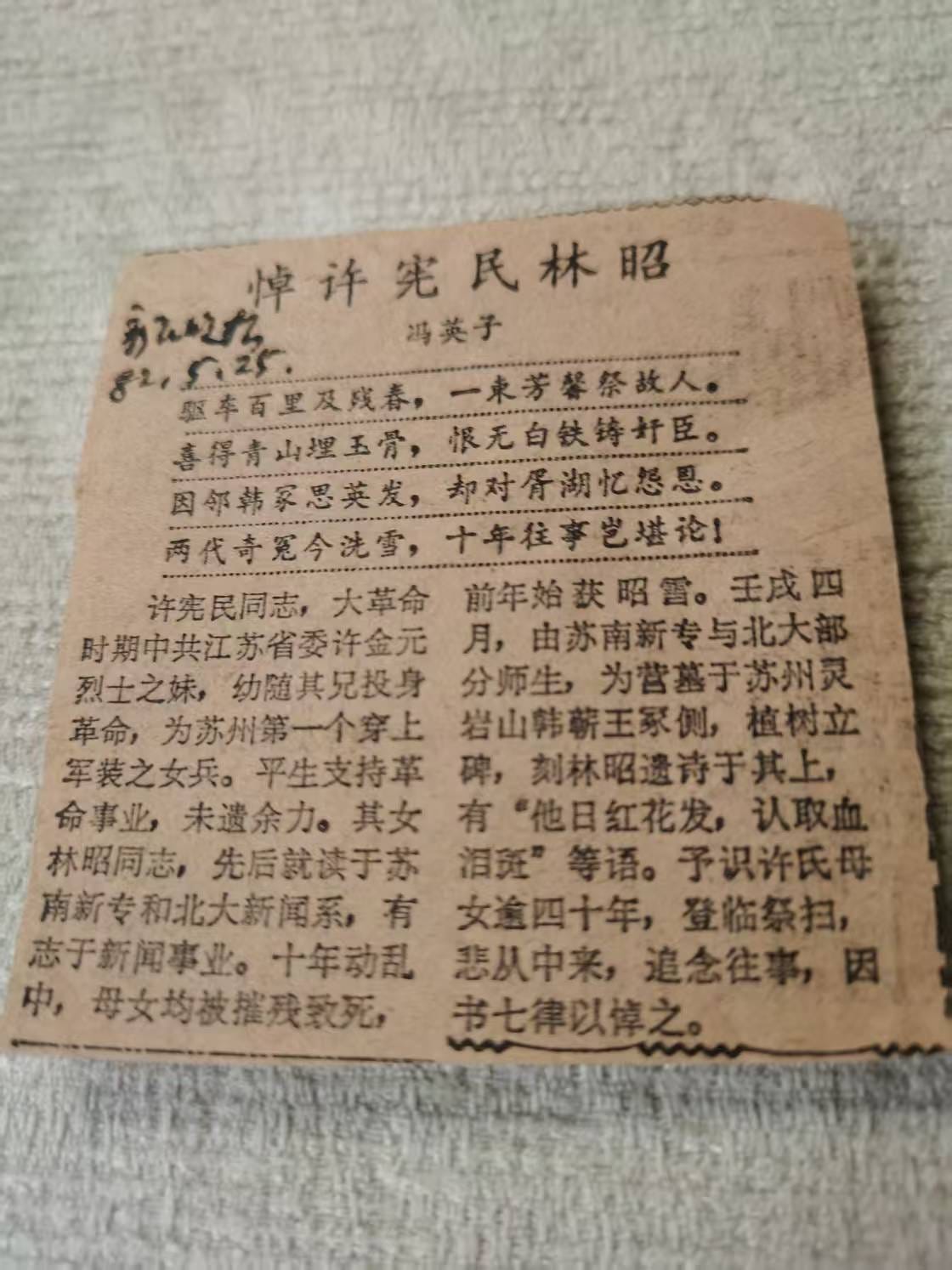

1982年5月25日,《新民晚报》上刊载了冯英子的短文《悼许宪民林昭》,母亲将剪报寄给了我。我从文中得知,林昭在苏南新专和北大的部分校友,在苏州灵岩山韩蕲王冢侧,为林昭与她母亲营墓建碑了。是淑贤提出来说,我们到苏州去纪念林昭。她说,你应该要去一次。当年8月,暑假期间,我们去了苏州,淑贤买了好多香烛带去灵岩。那时林昭的墓地还很小,就是一块碑而已。

结婚前,我向母亲要一个东西。我记得,小时候家里境况比较好的时候,父亲到南京路的首饰店买了一个翡翠的珠宝给母亲。母亲一直为我留着,哥哥和妹妹结婚,她都没有给他们。

那些年我在西宁,林昭罹难,他们还不知道。这个最好的、最贵重的纪念品,母亲说留给林昭。

“She Chose a Martyr’s Path”: Lin Zhao and Me (Part 2) (Selected Excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoirs)

Narrated & revised by Gu Yan

Written & compiled by Ai Xiaoming

Editor’s Note:

Professor Gu Yan, a founder of the influential underground journal Spark during the Great Famine, celebrated his 90th birthday on August 23, 2025. In 1960, he was arrested in Shanghai for his involvement in the Spark case along with the poet Lin Zhao and a friend, Liang Yanwu. Gu Yan was sentenced to 17 years in prison in 1965 and served his time in Qinghai. After his rehabilitation in 1980, Gu Yan began teaching at Lanzhou University as a theoretical physicist. He retired in 2001 and now lives in Hefei.

Although they both attended Peking University, Gu Yan was a physics student and did not know Lin Zhao, who was three years his senior and a journalism student in the Chinese department. Before secretly launching Spark in the northwestern city of Tianshui in 1959, Gu Yan personally inscribed Lin Zhao’s long poem “The Seagull” onto a mimeograph stencil, printed it, and shared it with friends. He also published another of her poems in the first issue of Spark. In 1960, while visiting family in Shanghai, he met Lin Zhao. Over the next three to four months, they corresponded frequently, developing a deep affection for each other and exchanging dozens of letters. Gu Yan and Lin Zhao were subsequently arrested. Lin Zhao was later released on bail but, after being re-imprisoned, she was tortured and executed on April 29, 1968.

This article, presented in two parts, is an excerpt from Gu Yan’s Memoir, compiled by Professor Ai Xiaoming. Here, Gu Yan offers a detailed, first-person account of his relationship with Lin Zhao and her connection to Spark. For the first time in 66 years, Gu Yan, one of the journal’s founders, provides a comprehensive look back at his life and the events of the Spark case. His deep affection for Lin Zhao and the “grief and shame” he felt upon hearing of her sacrifice while he was still in prison are profoundly moving. As a direct participant and witness, Gu Yan’s memoir holds immense historical value.

The China Unofficial Archives is honored to be the first to publish this work, which sheds light on the creation of one of the most important underground magazines in the history of the People’s Republic and commemorates Lin Zhao, an important intellectual who gave her life in her fight against tyranny.

The Chinese title of this article (“She walked the path of Xia Yu”) refers to a revolutionary character from a Lu Xun short story, based on the real-life revolutionary and martyr Qiu Jin. After Lin Zhao’s execution, the grief-stricken Gu Yan, who was still serving his sentence in Qinghai, was unable to express his feelings openly in letters to his family due to strict censorship. Instead, he could only hint at the tragedy by saying that Lin Zhao “walked the path of Xia Yu.”

This is Part 2 of these historically important recollections. Part 1, which recounted Gu Yan’s first encounters with Lin Zhao and their relationship, was published earlier and can be read on the China Unofficial Archives website or on Substack.

1. Lin Zhao Released on Bail

From early 1961 until the verdict came down on May 31, 1965, I was imprisoned for four years and five months at the Shanghai No. 2 Detention Center. Lin Zhao, Liang Yanwu, and I were charged in the same case. I still have the indictment from August 1, 1962, and the verdict from May 31, 1965. In both documents, the three of us, all Peking University alumni, were listed as co-defendants, with me as the principal offender, listed first. The indictment noted that Liang Yanwu and I were “currently in custody,” while Lin Zhao was out on bail, “temporarily residing at Lane 159, No. 11, Maoming South Road.”

[The indictment, drafted by the Shanghai Jing’an District Procuratorate, bore three numbers: 416, 423, and 431. The indictment with Lin Zhao’s handwritten annotations, which was later included in The Collected Works of Lin Zhao, was a separate document for her alone, bearing only her name. The indictment for Lin Zhao from November 4, 1964, was signed by the same prosecutor, Wu Zegao, as the one for Gu Yan, Lin Zhao, and Liang Yanwu dated August 1, 1962. Lin Zhao noted in a note she wrote in prison in blood: “Received at 7:50 a.m. on December 2, 1964.” This indictment was numbered 423, indicating that the number 423 belonged to Lin Zhao. It can be inferred that Gu Yan’s number was 416, and Liang Yanwu’s was 431. Since the three were listed as co-defendants, the earliest indictment from 1962 included all three numbers. The 1965 verdict for the three had a separate number, “No. 171 of 1962.”]

When I saw in the August 1962 indictment that Lin Zhao had been released on bail, I was very happy for her. The guilt I felt inside finally lessened. She hadn’t really done much; I was the one who got her involved. I thought that as long as she was safe and sound on the outside, she was free from our case.

I believe her release on bail was tied to the overall political climate at the time, not special treatment for her. The political winds had started to change after the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference, which the Central Committee held in Beijing from January 11 to February 7, 1962 in the aftermath of the Great Famine. We heard the news while reading the newspaper in our cells; otherwise, she would never have been let out. Her mother, a member of the Suzhou People’s Political Consultative Conference and an influential figure, may also have been working on her behalf in Shanghai.

After being inside for over a year, the case was scrutinized over and over, and they must have gotten a clearer picture. In the beginning, the interrogators were very aggressive, but then I noticed a change; they became more polite.

Furthermore, the letters Lin Zhao sent me proved that she hadn’t been involved in our activities and didn’t know the details, so they released her first.

The change in the situation in 1962 also brought me some special privileges. Around the time Lin Zhao was released, a doctor suddenly came to my cell door. She told me to stand up and said, “You look unwell.” I thought to myself, “How could I look well? I have been locked up for so long, not getting enough food, and haven’t seen the sun for ages.” I didn’t have a mirror, but I knew what I looked like.

In truth, being treated as a patient was just a matter of a single word from above. Soon after, without any physical examination, I was moved to the sick ward on the second floor. Regular cells were crowded with three or four people, but the sick ward had single rooms.

I stayed in the sick ward for over a month, eating patient’s meals, and the conditions were a bit better.

Speaking of food, when I first entered the No. 2 Detention Center, we had watery porridge for breakfast and dinner. It was served in an aluminum tray, one per person. We called it “four-eyed porridge” because there was so little porridge that you could see two “eyes” in it. We also got a little bit of preserved vegetables.

For lunch, we had sweet potatoes. Steamed red yams, a large portion of half to one kilogram, enough to fill us up. Later, lunch was changed to rice in a small aluminum tray with a little bit of vegetables, not nearly enough to feel full.

We were also allowed to receive support from family at the No. 2 Detention Center, like ten eggs a month. I asked my family to send goose eggs, which were bigger than duck eggs. Later, they couldn’t buy eggs, so they started raising chickens in a loft. My sister would bring me ten eggs every month during those years.

On October 1, 1962, for National Day, I was in the sick ward and was allowed to make a big purchase. This meant I could buy a few daily necessities using the money I had with me when I was arrested or money my family deposited for me. On that holiday, the inmate who brought the food told me I could buy half a kilogram of pig’s head meat and a quarter kilogram of candy, which other inmates couldn’t. He said it was special treatment, just like the cadres. They only got those two things for the holiday. I hadn’t eaten meat in a long time, and I finished the pound of pig’s head meat in a few days. The quarter kilogram of candy lasted a bit longer.

Another very important development was that our case was split for a separate trial. The three of us were separated from the Spark case in Tianshui, Gansu, to be tried and sentenced in Shanghai, not in Gansu. The head of the procuratorate came to interrogate me and told me they had won a legal battle. I didn’t understand at the time. He said, “Don’t worry, it’s been decided. Your case is under our jurisdiction. Tianshui wanted to merge the cases, but we disagreed.” He knew that I had left Tianshui at the end of 1959, Lin Zhao was in Shanghai, and Liang Yanwu was in Beijing and Guangzhou, so we had no connection to the activities Zhang Chunyuan was involved in back in Tianshui. So they insisted on keeping the cases separate. I thought it was very strange that he would tell me something so important.

If the case had been turned over to Tianshui for trial, our outcome would have been much worse, and it would have been much harder to get our names cleared later. By remaining in Shanghai and being tried separately, the power to handle our trial, sentencing, transfer to a city prison, and our files all stayed in the hands of the Shanghai authorities. The head of the procuratorate also told me, “If you behave well, we’ll give you a lenient sentence.”

My impression of the staff at the No. 2 Detention Center was a little better. They respected the inmates’ dignity. Why was this? I was told the prison warden was an underground Communist Party member before the liberation and had worked in the prison. He had no respect for the way the Nationalist Party ran things, and after the liberation, he became the head of the prison. He was a very impressive man. The inmates rumored that he was a holdover from the former Nationalist Party prison, but that wasn’t true. The Communist Party had infiltrated many key institutions, including the prisons. So after liberation, he took over as the person in charge. Some of the staff at the No. 2 Detention Center were also holdovers, and they might have helped the Communist Party before. The warden, being an old-timer from the underground party, knew the place best. In 1961, Shanghai’s food supply was still tight, but he made sure the inmates’ food rations were guaranteed. After Lin Zhao was arrested for the second time, she was held at the No. 1 Detention Center, which was completely different from the No. 2 Detention Center. From what Lin Zhao wrote, she was brutally persecuted there.

2. Lin Zhao Came to My Home

I waited until May 31, 1965, at the No. 2 Detention Center, when the verdict finally came out. I was sentenced to 17 years, Lin Zhao to a longer term of 20 years, and Liang Yanwu to 7 years. It was only then that I learned Lin Zhao had been rearrested.

The three of us were transferred to the Shanghai City Prison at Tilanqiao at the same time. After the verdict, a vehicle took us there. I didn’t see Lin Zhao at the trial, but I saw Liang Yanwu in the vehicle during the transfer. For the first time in five years, we saw each other up close.

We both had our belongings with us. My luggage included some foreign-language books my family had brought for me. I figured since his family was from outside Shanghai, no one would have sent him any books, so I gave him two of my foreign-language physics books.

When we entered the prison, we had to have our photos taken and were then assigned to different cells. Liang Yanwu was assigned to Cell No. 6, and I was assigned to Cell No. 1. He was later sent to the Baimaoling prison in Anhui Province to serve his sentence. Although his term was ten years shorter than mine, he couldn’t leave the camp after his sentence ended. It wasn’t until the end of the Cultural Revolution and the overturning of the unjust cases that he was able to return to Beijing to be reunited with his wife and daughter. He wasn’t able to get his teaching position back in the physics department at Peking University and instead went to teach at a textile college.

After the verdict, my family was allowed to visit me at Tilanqiao. The first to visit were my mother and my sister. Many visitors were there that day, with at least ten windows, all with iron bars. My mother and sister handed the things they brought for me to the guards, who would pass them to me. We could talk, but every inmate was being watched. Gu Mi was quick-witted and brave. She even dared to say, “Lin Zhao came to our home to find you!”

I thought, “Someone is right there watching! How can you say that?” She told me, but I didn’t dare respond. The person monitoring us probably didn’t know who Lin Zhao was, but I was a little nervous because it was my first visit, and the guard was right there, listening to everything we said.

That’s how I found out Lin Zhao had been to my house. I hadn’t seen my family for five years; this was the first time. I cried when I got back to my cell.

My mother was very sad, but my sister was young, not even 28, and she wasn’t so emotional. She said Lin Zhao had been to our house several times. This is how I learned how Lin Zhao felt about me. She didn’t avoid our relationship because I had gotten her involved, nor did she restrain her distinctive personality to hold on to the freedom she had just regained.

And so, the problems began. Lin Zhao, who was released on bail on March 5, 1962, was completely different from the Lin Zhao who had kept her distance from our political activities before. Compared to the Lin Zhao in “My Thought Process,” she had undergone a 180-degree transformation. After her release, she didn’t settle down but became more radical in her actions. I couldn’t have known about her later situation in prison. I only learned about it bit by bit after my release and after my exoneration in 1980. I have the following analysis: when she was told she was being released on bail, she hadn’t expected to be the only one let out while the rest of us were still locked up. She saw this as a great insult to her character and flatly refused to leave the prison. Her younger sister talked about the situation at the time.

[Lin Zhao’s younger sister, Peng Lingfan, once recounted to the journalist Zhang Min: “She said, ‘They’ve released me, and now they are going to arrest me again, what’s the point of this trouble?’ So she held on to the corner of the table. My mother and I went to pick her up, but she refused to come out, and the people inside didn’t know what to do. The precinct officers told my mother, ‘Just find a way to take her away.’ My mother then called a friend of hers, whose family had a gardener, who came and helped put her on a tricycle to take her back home.”]

After Lin Zhao was released, she often came to my home and even wrote a letter to Lu Ping, the president of Peking University, asking him to speak up for the students. Her mother found out and thought this was not a good idea, so she wanted her to go back to Suzhou to avoid Shanghai, where the case started. As a result, she met Zhu Hong and Huang Zheng there and started an organization with a manifesto. She had a personality where the more you tried to stop her, the more she would want to do something new and go her own way.

When I read “My Thought Process,” I thought that after her first arrest, she resented me for getting her involved. But after she was released, she felt she owed something to us. She must have thought, “You will think that I wrote that ideological self-criticism and drew a line between myself and you, and that’s why they released me. They must have been lenient with me because I confessed to something.” She wanted to prove that this wasn’t the case! So her first step was to come to my home to make it clear: I did not betray Gu Yan. She had to explain this to my family. That’s my guess about her state of mind.

So she told my sister that she took a bag and went to the Jing’an police sub-bureau to stage a sit-in, demanding to be arrested again. The meaning of this was, “You shouldn’t have arrested me in the first place, but you shouldn’t be releasing me either—if you release me, release everyone. It’s not only that I’m innocent; we’re all innocent. Since you won’t release them, you shouldn’t release me.”

I believe she realized at that point that she had gone too far in “My Thought Process” by writing that what we did was meaningless. Now that she was out on bail because of it, it was an insult to her moral conscience.

You might say a person wouldn’t risk their life out of personal feelings, but this wasn’t just personal feelings. Her actions were based on her own independent political beliefs. And a person’s beliefs are supported by their moral character. Didn’t I tell you the story of “The Great Famine of Qi” from the Warring States period?

There was a great famine in Qi. Qian Ao prepared food by the roadside, waiting to feed the hungry. A hungry person, covering his face with his sleeve and shuffling his feet, stumbled toward him. Qian Ao, holding the food in his left hand and the drink in his right, said, “Hey! Come and eat!” The hungry man looked at him and said, “I have never eaten food offered with such a shout, and that is why I have come to this!” Qian Ao then apologized, but the man still refused the food and died. Zengzi, hearing this, said, “Alas! He could have left when called with ‘hey!’, and eaten after the apology.” (Book of Rites, Tangong)

This man was so offended by being told “Hey! Come and eat!” that he would rather starve to death than eat under insult. Lin Zhao was like that: moral integrity was more important than anything. It was her top priority in life, and there could not be the slightest blemish. That’s why her first step after being released was to go to my house to make a statement: “The reason I was released and Gu Yan wasn’t is not because I wrote a self-criticism and drew a line between myself and you. I wanted to stay inside. I didn’t want to be released alone.”

Ni Jingxiong also told me that when Lin Zhao went to see her after her release, she looked like she had changed a lot and become completely different. Lin Zhao must have learned from her mother that after Zhang Chunyuan broke out of prison in 1961, he had traveled from Gansu to Suzhou, looking for her along the way. He had gone to my house in Shanghai to look for me, and then to Suzhou to find her. After Lin Zhao was released, she did the same thing; she wanted to find out where the rest of us were. When she found out she was the only one who had been released and that I and the others were still locked up, she couldn’t accept it.

3. Gu Mi’s Memory: “Lin Zhao Came Often Back Then”

Gu Mi: It was early spring in 1962, after Lin Zhao was released. She came to my house alone one afternoon. At that time, we lived at No. 23, Lane 552. The ground floor of our building had been converted into a public canteen. Many people were coming and going, eating there, so it was easy for her to come without drawing attention.

When summer came, my parents went to the countryside to stay, so it was just my brother and me at home. Lin Zhao came often and talked non-stop with my eldest brother, Gu Hong. My eldest brother was influenced by her, and after their case was announced at the end of May 1965, Gu Hong anonymously mailed a copy of a Chinese translation of Fidel Castro’s book History Will Absolve Me to the judge at the Jing’an District Court.

Lin Zhao gave me the letter she wrote to Lu Ping, the president of Peking University, and the poems she wrote. I also showed them to my father. She liked to write modern poetry. At our house, she talked about everything. Sometimes she would just talk by herself without needing a reply. She talked about people starving to death in Anhui because there wasn’t enough to eat. She seemed to know about everything. I wrote it down in my diary, which was confiscated when our house was raided during the Cultural Revolution. This became a significant part of my “crimes.”

She came to our house again and again, but no one ever came to question us about it. Later, Gu Yan said, “Of course no one came to question us, because the police intentionally released her to see who she would contact, and who else was still at large, not yet captured. They wanted to find the person behind the scenes who hadn’t been arrested, especially the one called ‘Big Brother.’”

4. Vautrin, Lu Fan, “Big Brother”

[Ai Xiaoming: Who was “Big Brother”? Thirty-seven years later, on March 16, 1999, Lin Zhao’s classmate and confidante Ni Jingxiong wrote a letter to Gu Yan, asking about the whereabouts of this “Big Brother.”

Ni Jingxiong wrote: “There’s one more thing; we are still trying to find someone, a ‘Big Brother’ whom Lin Zhao greatly admired. He was said to be a college student exiled in Gansu (where you all were sent), who once escaped from prison, and was nicknamed ‘the great bandit of rivers and oceans.’ According to Huang Zheng, who was prosecuted in the same case as Lin Zhao in Suzhou, Lin Zhao was always hoping to see ‘Big Brother.’ I wonder if you know what kind of person he was, and if you have any news about him?”]

Gu Yan: During my interrogation, they asked, “Who is ‘Big Brother’?” I said, “‘Big Brother’ is Zhang Chunyuan.” In her letters to me, Lin Zhao didn’t use Zhang Chunyuan’s name but referred to him as “Big Brother,” for example, asking, “How is ‘Big Brother’ doing?” Besides Lin Zhao, no one else among us called Zhang Chunyuan “Big Brother.”

[Ai Xiaoming’s note: On August 10, 1961, Zhang Chunyuan escaped from prison. He then traveled on foot from Lanzhou to Shanghai, and from Shanghai to Suzhou. In Suzhou, he met Lin Zhao’s mother and learned that Lin Zhao had been arrested. He then returned to Shanghai and sent Lin Zhao a postcard. Lin Zhao certainly never received this postcard; it was intercepted by the No. 2 Detention Center and later transferred to Zhang Chunyuan’s case file in Tianshui. Forty-six years later, when Tan Chanxue was looking for Zhang Chunyuan’s case file in Tianshui, she found this postcard and used it as an illustration in her book, Sparks: A Chronicle of the Rightist Counter-Revolutionary Group at Lanzhou University.

Based on the postmark in the upper right corner, the postcard was mailed from Shanghai on September 1, 1961. The recipient’s address was “No. 99, Sinan Road, this city,” which was the address of the No. 2 Detention Center. The postcard was bound in the case file, and the text on the right side was incomplete. The message was written on the left side. Tan Chanxue quoted the following parts:

“Lin Zhao: I am unable to visit you. All I can do is circle these red walls twice, a small token of my affection. Please accept this improper consolation.”

Another part Tan quoted was probably written on the back of the postcard:

“The material of our life is so rich and interesting that a book could be written about it, a book that has never existed before in ancient or modern times, in China or abroad. I hope you can adopt a ‘take it as it comes’ attitude, without being anxious, and read this useful, rare book well, so that you can serve the people better in the future... We are open and honest, with a clear conscience, and dare to fight. Only those who dare to fight can dare to win.”

In the middle of the left side of the postcard illustration, there are six more lines of text that Tan Chanxue did not quote, but they are very important. I will add them here:

“You may be wondering why I came to Shanghai. It’s simple, Mr. Vautrin is a ‘ghost-catcher,’ and some people want his ‘Big Brother’ to walk freely. As for your life and studies there, I have 390 days of personal experience. The material for it...” (end of text on the left side of the image).

Tan Chanxue wrote in Sparks that Zhang Chunyuan wrote a letter to Lin Zhao in the name of her mother. But if we consider the hints of “Vautrin” and “ghost-catcher,” it’s clear this is not a mother’s tone. Vautrin is a character in Balzac’s novel Old Goriot, an escaped convict who is full of tricks. Zhang Chunyuan must have believed that Lin Zhao would understand that “Big Brother” had successfully escaped from prison. In addition, on the right side of the postcard, in the address field for the recipient, the first character is in a continuous stroke that looks like the simplified character for “mother” (亲), but it is actually closer to the cursive form of “Zhang” (章). Zhang Chunyuan’s pen name for the script The Sons and Daughters of China and Korea, published in the June 1959 issue of Film Literature, was “Sima Zhang.” If Lin Zhao had actually received this postcard, she would have known who the sender was.]

Gu Yan: Zhang Chunyuan came to my house on Xikang Road. The first time, he and Tan Chanxue came from Henan. I went to Heiqiao to pick them up and took them to the countryside to stay. So both he and Tan Chanxue knew my address on Xikang Road in Shanghai.

Gu Mi: I saw Zhang Chunyuan walking into the lane. I was at the window doing some chores, or something like that. It must have been around noon; many people were eating at the canteen below. No one paid attention when he went upstairs.

My mother and I lived in the big room, which was the main room facing south; my father slept alone in the small room on the north side, the loft. Zhang Chunyuan walked directly to the loft, as if he knew where it was. That detail left a deep impression on me.

My father was in the loft. About five or ten minutes later, he came into my room to find me. He said, “Zhang Chunyuan is here. Give him the national grain coupons.”

We didn’t invite him for a meal. My father must have told him that I had been arrested and that our home had been searched. I saw him leave. He didn’t come into the big room to say hello to me. He must have intentionally avoided me so as not to have any direct contact.

When he left, I watched him from the window. He walked straight ahead without looking back. As he was about to reach the entrance of the lane, he turned his head and looked back. Then he turned around and walked away slowly.

Later, my father came over and told me, “Zhang Chunyuan escaped from prison.”

After he left, things got complicated. Two men came with a photo of Zhang Chunyuan and asked my mother, “Do you know this man?”

I don’t know who these two men were; I was at work and didn’t see them. My mother hadn’t seen Zhang Chunyuan that day, so she must have said she didn’t know who he was.

A neighbor in the lane told my mother, “Someone came to your house? The police asked us to look at a photo.” But they couldn’t see clearly and couldn’t identify him. With so many people in the lane and people coming and going at the canteen, they just thought he was someone who came to eat. Who would pay attention? No one did.

He was wearing a dark Zhongshan suit. It was autumn.

Gu Yan: The Jing’an police always thought that “Lu Fan,” the person who wrote the postscript to Lin Zhao’s poem “The Seagull,” was a seasoned professional. The postscript noted a date before 1949, so they desperately wanted to find out who this person was.

I told them “Lu Fan” didn’t exist; it was a pseudonym. Whose pseudonym was it? I said it was mine, and that I wrote the postscript. Why did I say that? It was a trick I played on them. First, I wanted to send a message to Zhang Chunyuan to let him know I was also arrested. My confession would definitely be used by the police to confront him, and once they did, he would know my situation. Also, it was a matter of loyalty. I didn’t want him to think I had betrayed him; he knew what kind of person I was. He probably couldn’t have imagined that I would insist that I wrote the postscript. Zhang Chunyuan might have thought, “Gu Yan is quite something.”

Tan Chanxue wrote in her book Sparks: “Zhang Chunyuan and Gu Yan wrote the postscript separately, and in the end, they adopted the one written by Gu Yan, but Gu Yan himself doesn’t remember, and to this day he still thinks it was Zhang Chunyuan who wrote the postscript. He only remembers why the pseudonym ‘Lu Fan’ was used, which was an homage to Lu Xun.” How could I not remember? I did it on purpose. Zhang Chunyuan would have certainly admitted that he wrote the postscript, and when the case worker confronted him, he would have understood that I was deliberately lying, and then he would have just made up a story, saying that the two of us wrote the postscript separately. The authorities in Tianshui were fooled, but the Jing’an police sub-bureau felt something was fishy. They thought it was possible that both I and Zhang were lying, intending to protect this person named “Lu Fan.” And when Tan Chanxue wrote that Zhang Chunyuan and I “wrote separately,” I think she must have seen my confession in the case file, but she didn’t show me the documents.

When Zhang Chunyuan escaped that time, if he was trying to stay alive, he ran in the wrong direction. He shouldn’t have run south. If he had run northwest, toward the ethnic minority regions, he was very good at surviving. In those places, household registration management wasn’t as strict as it was in Shanghai. But he ran here because he wanted to find us, and all of us had been arrested!

The documentary by Hu Jie said that Lin Zhao was released to find Zhang Chunyuan, but that’s not accurate. When Lin Zhao was released in March 1962, Zhang Chunyuan had already been caught on September 6, 1961. One reason for Lin Zhao’s release was, as I said before, that the situation had relaxed. The other reason was to see who she would contact after she was released. They weren’t trying to catch small fry; they were looking for a big one, for instance, who “Lu Fan” really was. Then, after Lin Zhao was arrested for the second time, they released Zhang Ruyi in the summer of 1963 and had Zhang Ruyi contact my sister in the name of being Lin Zhao’s cellmate. Zhang Ruyi also went to Suzhou to continue looking for “Big Brother.” This shows they didn’t believe what I said and thought “Big Brother” was someone else, not Zhang Chunyuan, and that he was still active on the outside.

5. Zhang Ruyi Came Looking for “Big Brother"

Gu Mi: After Zhang Chunyuan left, a while later, Zhang Ruyi came. As soon as she came, she asked me, “How is ‘Big Brother’ doing now?"

What did Zhang Ruyi look like? It’s been over 60 years; I don’t remember. I also don’t know why she was arrested. Her family was in a distant suburb of Shanghai, and she spoke with a Shanghai accent. I know where her home was; it was all countryside there. Her mother was still alive, but her father was gone; he must have had some kind of problem. She was still very young then, maybe not even 20, perhaps 18 or 19. She had two braids and looked like a middle school student. She told me Lin Zhao had asked her to come and even brought a handwritten letter from Lin Zhao.

I don’t remember what Lin Zhao wrote. All I know is Zhang Ruyi said she and Lin Zhao were in the same prison. She talked about some of Lin Zhao’s situation, and it didn’t sound made up. Maybe the Jing’an police sub-bureau intentionally put them in the same cell in the Tilanqiao City Prison.

[Ai Xiaoming’s note: Lin Zhao was arrested for the second time on November 8, 1962. On December 23, she was put in the Tilanqiao City Prison, where she was held for eight and a half months. The city prison was originally for convicted prisoners, but putting the unconvicted Lin Zhao there might have been a deliberate arrangement. An inmate in the same cell as Lin Zhao, named Zhang Ruyi, was labeled a “fraudster” on Lin Zhao’s indictment, but Lin Zhao noted on the indictment that Zhang Ruyi was a political prisoner. In July 1963, when Zhang Ruyi was released, she was given a special assignment by the police. She first went to Gu Yan’s home in Shanghai, then to Suzhou, where she found Lin Zhao’s friends Zhu Hong and Huang Zheng.]

Gu Mi’s diary from that day recorded Zhang Ruyi’s visit:

The text starts from the second to last line of the left page and continues to the seventh line of the right page:

July 19, 1963

Yesterday, an unexpected guest came, someone who had been tested for three years, and though younger than me, had more experience.

Due to Lin’s influence, even though her family is currently in trouble, she is full of confidence in the future.

Yes, there is no reason to say that today’s youth have no future, but time is merciless. Our age is increasing, and the best years of our lives don’t wait for anyone. Our generation has been truly unlucky.

I plan to go see her. This morning, I sent a letter to my little older brother, telling him to wait patiently.

Gu Mi: Zhang Ruyi asked me to meet her at Fuxing Park. Every time, she would insist on asking about “Big Brother.” I told her, “My brother is at work now. He’s doing pretty well.”

At that time, I didn’t know she was sent by the prison. I believed she was with Lin Zhao and had just been released. Because of my relationship with Lin Zhao, I took good care of her. When she needed to borrow money or books, I agreed.

[Gu Mi’s diary entry from August 30, 1963, mentioned: “She borrowed 8 yuan last week and took a few shirts, which made our finances so tight we couldn’t even manage the money for various tickets.”]

Zhang Ruyi lived somewhere in Baoshan, I think. Once, she told me to go visit her hometown and that she had some companions there. What she said didn’t sound like a lie.

Soon after, my eldest brother, Gu Hong, told me not to have anything to do with her anymore and to keep my distance. What’s more, Gu Hong never spoke a word to her. She would just latch onto me and tell me where to meet. Every time, she would keep asking about “Big Brother.” Eventually, I got angry and said, “You keep saying ‘Big Brother,’ but we only have one ‘big brother.’ We don’t call him ‘big brother,’ we call him ‘a-ge’ [older brother in Shanghai dialect]. Who are you talking about? There’s no one by that name!”

She stopped coming after that.

So who was “Big Brother”? The mystery was revealed later. One time, my mother was tidying things up and found an empty box in a chest of drawers. My mother told me this box was left by Lin Zhao and that I should take a look at it and not throw it away. Several years had passed by then, maybe 1967 or 1968; Lin Zhao had already been rearrested. Anyway, my mother showed me a box that used to hold Suzhou dried tofu. I said, “Why are you keeping an empty box?” We opened it. My mother lifted the lid and saw nothing. But there was a piece of paper on the bottom. When she lifted the paper, there were a few characters written on the bottom of the box. The heading was “Big Brother.” I don’t remember what the message was; it was a very simple sentence. I also don’t remember if Lin Zhao’s name was at the bottom. I remembered “Big Brother” because Zhang Ruyi kept asking about him all the time. I suddenly understood. The person she was looking for was this “Big Brother.” Zhang Chunyuan. You called him “Big Brother,” right? This box might have been left for us to keep. Inside, she left this short message for Zhang Chunyuan.

After Zhang Ruyi left, a man came. He said he was in the same cell as Gu Yan and knew everything about his situation. This man was in his early 30s and didn’t look like a young person. He came just as our loft was empty. He said he wanted to live with us and that he would pay us 50 yuan a month. Back then, our salary was only around 50 yuan, so that was a lot of money. My father hesitated, but I said no. I said, “Where would you live? We only have two rooms.” So I refused.

He seemed like he wanted to be my boyfriend. I ignored him and had nothing to say to him. Why? Because later, he told my father that he was at the hospital in Jiangwan and that I had to go see him. I found this very repulsive. My parents didn’t force me. Maybe he gave my parents some kind of benefit? It didn’t seem so. Anyway, this man insisted that I go to Jiangwan once, but I never did.

At that time, we were raising chickens in the loft where the bed used to be. We couldn’t buy eggs then, so we raised chickens to eat their eggs and to send the eggs to Gu Yan. I was chopping vegetable peels at the windowsill, preparing food for the chickens, and this man sat across from the counter. I just kept chopping without paying him any attention. He didn’t leave. There were five or six chickens and a duck there. He came about two times. He told us he was with Gu Yan.

Gu Yan: I remember this person. When I was first arrested, everyone had to sit in a corner. After a certain period, we could get up and walk around the cell in a line. He followed me. I remember he suddenly told me that he was from the army and was Peng Dehuai’s subordinate... I became very alert right away. He was that old and came to find me specifically; he must have been sent by the police. I ignored him, and after two times, he stopped coming.

Gu Mi: How did you know?

Gu Yan: There were all sorts of people in the cells, so of course, I knew. I guess that’s the same person. During that time, there was also a young man, 15 or 16 years old, who said he was arrested trying to escape to Hong Kong. I believed what people like him said. But that man who said he was Peng Dehuai’s subordinate from the army... I knew he was shady as soon as I heard it. He was so much older than me. I was still a young man then.

Every time we could get up and walk around, he would follow me. Later, he disappeared, as there were many people coming and going.

6. Separate Indictments, Same Verdict

[Peng Lingfan: “Because the main perpetrators were only sentenced to seven years, Lin Zhao’s sentence was the heaviest. So my mother always felt that her Rightist friends were not fighting the Communist Party as she was, or that they were pushing everything onto her. Because for a while, my mother had so many letters written to the prison warden, I don’t know how many, maybe hundreds, even thousands.”]

In the verdict for the three of us—Lin Zhao, Liang Yanwu, and me—Lin Zhao’s sentence was indeed the heaviest. I was the first defendant, sentenced to 17 years. Lin Zhao was the second defendant, sentenced to 20 years. Liang Yanwu was the third defendant, sentenced to 7 years. Please note that the verdict number was “No. 171 of 1962.” It was from the same year as the indictment I had (August 1, 1962), but the verdict wasn’t issued until almost three years later, on May 31, 1965. Why?

During this time, Liang Yanwu and I were held in custody, but Lin Zhao was out on bail from March 5 to November 8, 1962. The reason the verdict was delayed for so long was that the Jing’an police sub-bureau wanted to expand their investigation and continue their dragnet. They believed their case hadn’t been solved. Even though Zhang Chunyuan had been caught, they wanted to continue looking for who “Lu Fan” really was and if he was “Big Brother.” That’s why Zhang Ruyi came to find Gu Mi and why that man who called himself “Peng Dehuai’s subordinate” came to my house to rent a room. Zhang Ruyi also went to Suzhou to find Zhu Hong and Huang Zheng, which resulted in Huang Zheng being sentenced to 15 years.

I couldn’t have known about Lin Zhao’s activities in Suzhou while she was on bail. In my own confession, I never pushed anything onto Lin Zhao. My essay consistently maintains that Lin Zhao was not directly involved in the Spark activities; she was, at most, a fellow traveler in our ideology. As for Liang Yanwu, he didn’t do much in terms of specific actions; he just passed on letters for Tan Chanxue and Zhang Chunyuan. He had never met Lin Zhao and couldn’t have pushed anything onto her.

Lin Zhao’s heaviest sentence among the three of us was mainly due to what she did while she was out on bail. There was another indictment just for her, dated November 4, 1964, that Liang Yanwu and I were not on.

Lin Zhao copied this indictment by hand. After she was exonerated, this manuscript and her other manuscripts were returned to Peng Lingfan and can now be found online. Lin Zhao copied it with many of her own refutations in parentheses between the lines.

This indictment, with the number 423, labeled Lin Zhao as the principal leader of the “Chinese Free Youth Militant League” counter-revolutionary group.

In the verdict from the end of May 1965, Lin Zhao was again included in the case with Liang Yanwu and me. The Spark case from 1960, Lin Zhao’s activities while on bail in 1962, and especially the things that happened in Suzhou that Zhang Ruyi had connected to eight months after Lin Zhao’s second arrest, were all merged into this one “counter-revolutionary group” case. The three of us were held in Shanghai, and we were sentenced at the same time as co-defendants.

To find out about Lin Zhao’s experiences, Ni Jingxiong tried to find Zhang Ruyi, but couldn’t. After my sister and my “counter-revolutionary” cases were overturned, Zhang Ruyi called my sister on her own. She apologized to my sister and admitted that she had taken on an assignment from the police. The police had promised to arrange a job for her, but they didn’t follow through. Zhang Ruyi later went to Xinjiang and had a very hard time. After the Cultural Revolution, she came back to Shanghai and lived in Pudong. I don’t know if she ever had her case overturned.

She was afraid to come to my home. She told Gu Mi, “Now they are all looking for me, and I was also deceived.”

7. “In Memory of Xia Yu”

While I was in the same city prison as Lin Zhao, I was transferred to the translation group, which was a kind of special treatment. Like most people, I adopted a submissive attitude. What was different for me was that from the No. 2 Detention Center to Tilanqiao, I was always reading and thinking about mathematics and physics problems. This was my spiritual solace and kept me relatively isolated from the pain of reality. I could say that my situation was more fortunate than many others.

I couldn’t see Lin Zhao, but I knew she was being treated as a negative example of resisting reform. Wu Mingwei asked me if I had ever thought about trying to persuade her. How could that have been possible? There was no way to contact her, and the prison authorities wouldn’t have let me.

In July 1967, I was sent to Xining, Qinghai, with a group of inmates with heavy sentences, to serve our time at the Qinghu Machinery Factory.

It was probably in January or February of 1969 that I learned Lin Zhao had been killed. An interrogator sent from Shanghai asked me, “Do you know that Lin Zhao has been executed?” I later wrote a letter to my father to tell him, but I couldn’t be direct, so I hinted: “Lin Zhao took the path of Xia Yu.” I thought the guards might know about Qiu Jin but not necessarily about Xia Yu from Lu Xun’s story. My father understood right away.

My mother kept my letters from Qinghai and bound them neatly. Later, when I saw my mother’s bound letters at home in Shanghai, I found one I wrote in March of that year:

Dad, Mom: I didn’t receive a letter from you this month. I wonder why? Last month, I wrote to you asking for five yuan. Did you send it? According to the government’s latest regulations, the address on your letters should now be changed to: “Qinghai Province, Xining City, Qinghu Machinery Factory, 8523 Gu Yan.” I’ve been in very good health lately. The other day, I went to the large furnace room to help pull some coal and weighed myself on the scale. I weigh 119 jin. I remember my highest weight before my arrest was 121 jin, and my highest weight after my arrest was 131 jin. At that time, in the sick ward at the No. 2 Detention Center, my lung disease was gradually getting better, and I had no emotional burden, so my weight naturally increased. A person’s physical health is not what’s important; what matters most is the quality of their thoughts. Some people, even after they have died, their spirit is passed down through the ages, which is a thousand times better than those who are alive but feel their lives are meaningless. In his essay “Medicine,” Lu Xun commemorated Xia Yu and added a wreath at the end of the text to represent hope. Looking back at my own life, I’ve made many mistakes. While feeling grief and shame, I can only honestly and diligently reform myself. Maybe I can add the most ordinary and insignificant little flower to our socialist motherland. That is my hope.

All the best,

Your son Yan

March 27, 1969

I couldn’t express my true feelings directly, so I could only hint with this circuitous language. Ultimately, my heart couldn’t let go, and I couldn’t help but add the word “grief” before “shame.”

My father understood as soon as he saw it. He hadn’t written to me for a year and five months. After receiving my letter, he wrote to me for two months in a row.

What could my father say? During the Cultural Revolution, my older brother Gu Hong was repeatedly criticized and denounced as an “unapprehended counter-revolutionary” for mailing that book, History Will Absolve Me, to the judge. They also investigated what he had said to Zhang Ruyi. He was so desperate under the immense pressure that he attempted suicide but didn’t succeed. My sister Gu Mi’s diary was confiscated, and she was sent to the Hongkou precinct detention center and labeled a “current counter-revolutionary”... (I will write a separate article about Gu Mi’s “diary crime” later). My father couldn’t tell me about the things that had happened at home. He could only encourage me with the most popular political slogans, telling me to “correct my empty and wrong thoughts.”

In my reply to my father’s letter, I directly wrote about Lin Zhao’s death: “Lin Zhao’s death will not affect my determination to reform.” My letter had to pass through the prison authorities for review, so I had to use such language that obeyed my true thoughts. I quoted a poem by Qiu Jin to tell my parents that I would not dwell in sadness, to relieve their worries: “I remember a previous person wrote, ‘Autumn wind, autumn rain, what a sad thing,’ which was a historical figure’s state of mind under specific circumstances. The times are different now. If I were to encounter rain in this situation, I believe I would be reminded of the new life that comes after the rain and would be filled with confidence and hope.”

On May 8, 1969, my father replied to me. In addition to cliches, he encouraged me: “Anyone who is progressing is forever young. I hope you hold on to your faith and courage to reform and never be discouraged.”

My father never wrote to me again after that. This was the last letter of his I kept and the last words he left for me.

8. She Suggested: Let’s Go Pay Our Respects to Lin Zhao

In 1974, I received a three-year reduction in my sentence for my achievements in technical innovation, but even after my sentence was completed, I was still forced to stay and work at the factory. I was just moved from the group of prisoners to the group of employees. I still needed permission to leave the factory area, and my letters to my family were still censored. At this point, I understood that no matter how long your sentence was or whether it was over, you were never truly free and could not leave the labor camp. It wasn’t until the end of the Cultural Revolution that the situation changed. By the end of 1978, a conclusion was reached on Peng Dehuai’s case from 1959. I knew that our case was related to how the so-called anti-Rightist movement of 1959 would be evaluated, so I saw a hope for our exoneration. My sister was exonerated that year, and I wrote to my mother, telling her that I believed my day would also come. On February 12, 1979, I submitted an application to the Shanghai Jing’an District Court, requesting a review of my case. I also wrote an appeal to the Lanzhou University Party Committee regarding my classification as a Rightist in 1958.

On March 2, 1979, Lanzhou University issued a notice rectifying my Rightist classification. I continued to press the court for a case review, but there was almost no progress. I learned from other sources that the main reason was that Lin Zhao’s case was difficult to overturn. I’ll describe the reasons and process in detail later.

On June 22, 1979, I recorded my state of mind during this period in my diary [referring to Zhang Zhixin, a woman in Liaoning Province who spoke out against Mao during the Cultural Revolution and was severely tortured and later executed]:

“The story of Zhang Zhixin’s deeds, widely publicized in the newspapers, stung my heart because it made me think of Lin Zhao and the difference in our choices in life. Every time I imagined the scene of Lin Zhao’s heroic execution, I would have a faint feeling that if I couldn’t contribute something to humanity in the years to come, my life would be shameful. How can I get rid of the dishonorable title of ‘survivor’? Like the protagonist in Resurrection, I must abandon everything and strive to save myself!”

I have told visiting friends on more than one occasion that I harmed Lin Zhao. The difference in our choices was that my resistance ended when I entered prison. But her resistance started when she left prison and continued until she fought to the death and gave her life.

On May 17, 1980, the Shanghai Jing’an District People’s Court finally decided to revoke our original sentence. The verdict stated:

“As for their disagreements with some of the Party and government’s mistakes in policy, their actions of discussing and writing articles to reflect the situation are correct. The original sentence of counter-revolutionary crimes was obviously inappropriate and a wrongful case that should be corrected.”

The court declared Liang Yanwu and me innocent and exonerated us. However, Lin Zhao, who was initially indicted and given a heavy sentence with us, was not on this verdict; only our two names were.

After a review of Lin Zhao’s case, three months later, on August 22, 1980, the Shanghai High Court declared her innocent. However, the reason given was that she had been stimulated and suffered from mental illness after the anti-Rightist campaign, and her mental illness relapsed after her wrongful conviction, and that her behavior during her illness should not have been considered counter-revolutionary and she should not have been executed.

In a letter to my mother on October 30, 1980, I wrote about my views on this verdict:

“Liang Yanwu wrote to say that the Peking University disciplinary committee had gone to talk to him, saying that Peking University wanted to hold a memorial service for Lin Zhao and asked for his opinion. They also asked for his opinion on the verdict that overturned Lin Zhao’s case. Liang’s answer was that it was not true that Lin had a mental illness since 1960. I think the resistance to overturning Lin Zhao’s case was at the Shanghai High Court. This current verdict is only a temporary compromise, because everyone knows in their hearts that Lin was not mentally ill. I don’t know how Peking University’s memorial service will be held.”

Due to Peng Lingfan’s appeals and the efforts of various circles, a new verdict was issued for Lin Zhao’s case on December 30, 1981. This verdict corrected the wrong statements in the previous verdict, declared Lin Zhao innocent, and completely exonerated her.

After my exoneration, I looked for Lin Zhao’s younger brother and younger sister. Her brother, Peng Enhua, still lived in the home on Maoming South Road, and her sister lived in a hospital dormitory. I had more contact with Peng Enhua. He was studying French at the time, and I gave him two large French dictionaries. I contacted Peng Enhua to arrange the funeral for Lin Zhao and her mother and to send wreaths in Suzhou. On behalf of both Liang Yanwu and myself, I expressed our condolences.

In July 1980, twenty-two years after I left Lanzhou University, I returned to teach in the physics department, starting as a teaching assistant. Through a teacher’s wife’s introduction, I married Gu Shuxian, a lecturer in the mechanics department, in July 1981. Before we married, I showed her my exoneration verdict and the article commemorating Lin Zhao that Chen Weisi published in Democracy and Rule of Law in March 1981.

On May 25, 1982, the Xinmin Evening News published a short article by Feng Yingzi, In Memory of Xu Xianmin and Lin Zhao. My mother sent me the clipping. From the article, I learned that some of Lin Zhao’s classmates from the South Jiangsu New College and Peking University had built a tomb and a monument for Lin Zhao and her mother near the tomb of King Han Qi on Mount Lingyan in Suzhou. It was Shuxian who suggested we go to Suzhou to pay our respects to Lin Zhao. She said, “You should go at least once.” That August, during the summer vacation, we went to Suzhou. Shuxian bought a lot of incense and candles to take to Lingyan. At that time, Lin Zhao’s grave was still very small, just a tombstone.

Before I got married, I asked my mother for something. I remembered that when I was little, back when our family situation was good, my father bought my mother a jade jewel from a jewelry store on Nanjing Road. My mother had kept it for me and hadn’t given it to my brother or sister when they got married.

Those years I was in Xining. When Lin Zhao died, they didn’t know about it. My mother said that this best and most precious memento should be kept for Lin Zhao.