政治反抗需要多元叙述:顾雁回忆录之《我与林昭》的意义

Political Resistance Requires a Plurality of Narratives: The Significance of Gu Yan’s Memoir, “Lin Zhao and Me”

作者:江雪

By Jiang Xue

The English translation follows below.

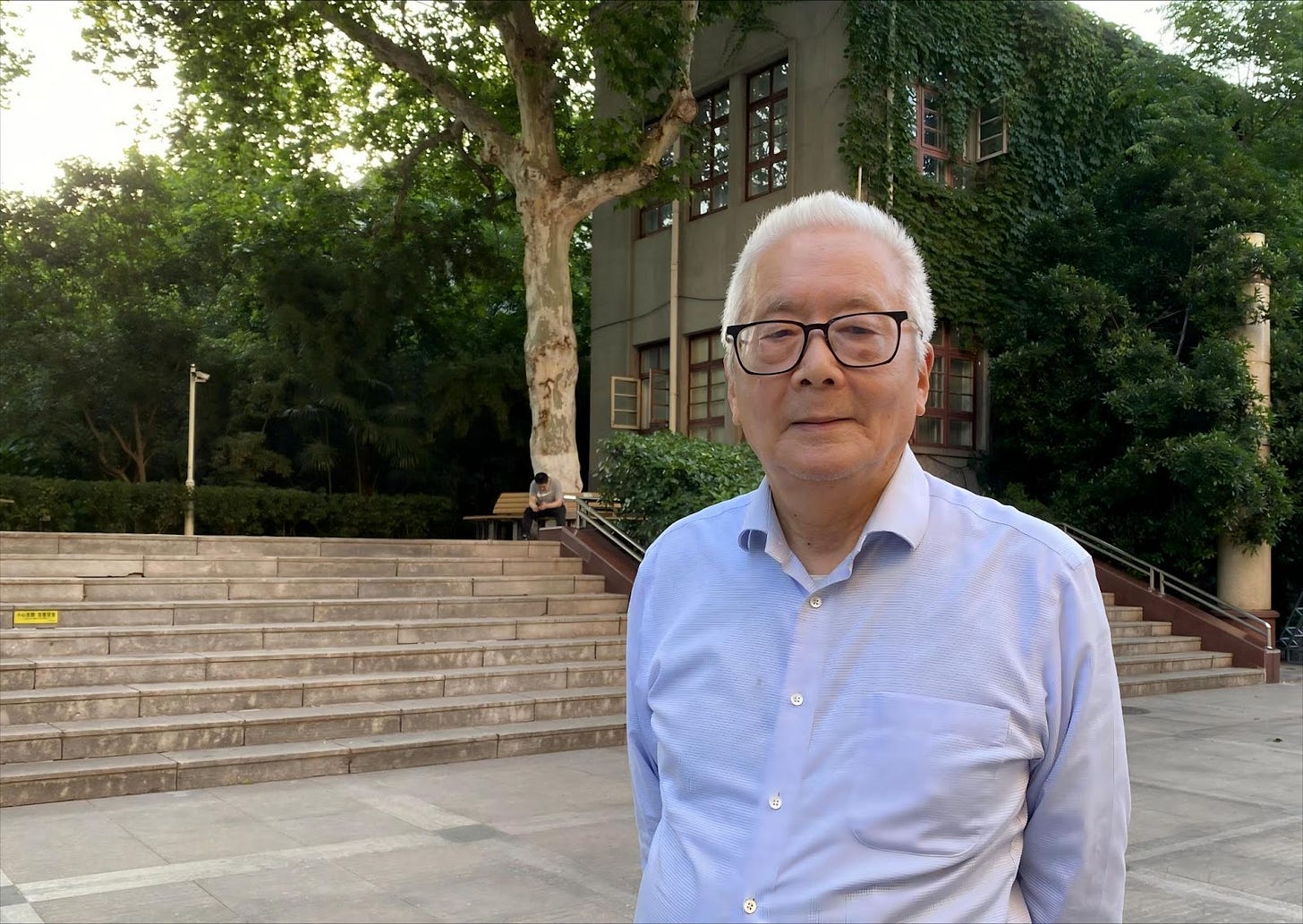

八月的安徽合肥,酷暑未退。在中国科技大学东校区一处老住宅楼里,刚出院的顾雁,在几位晚辈环绕下,度过了他90岁的生日。

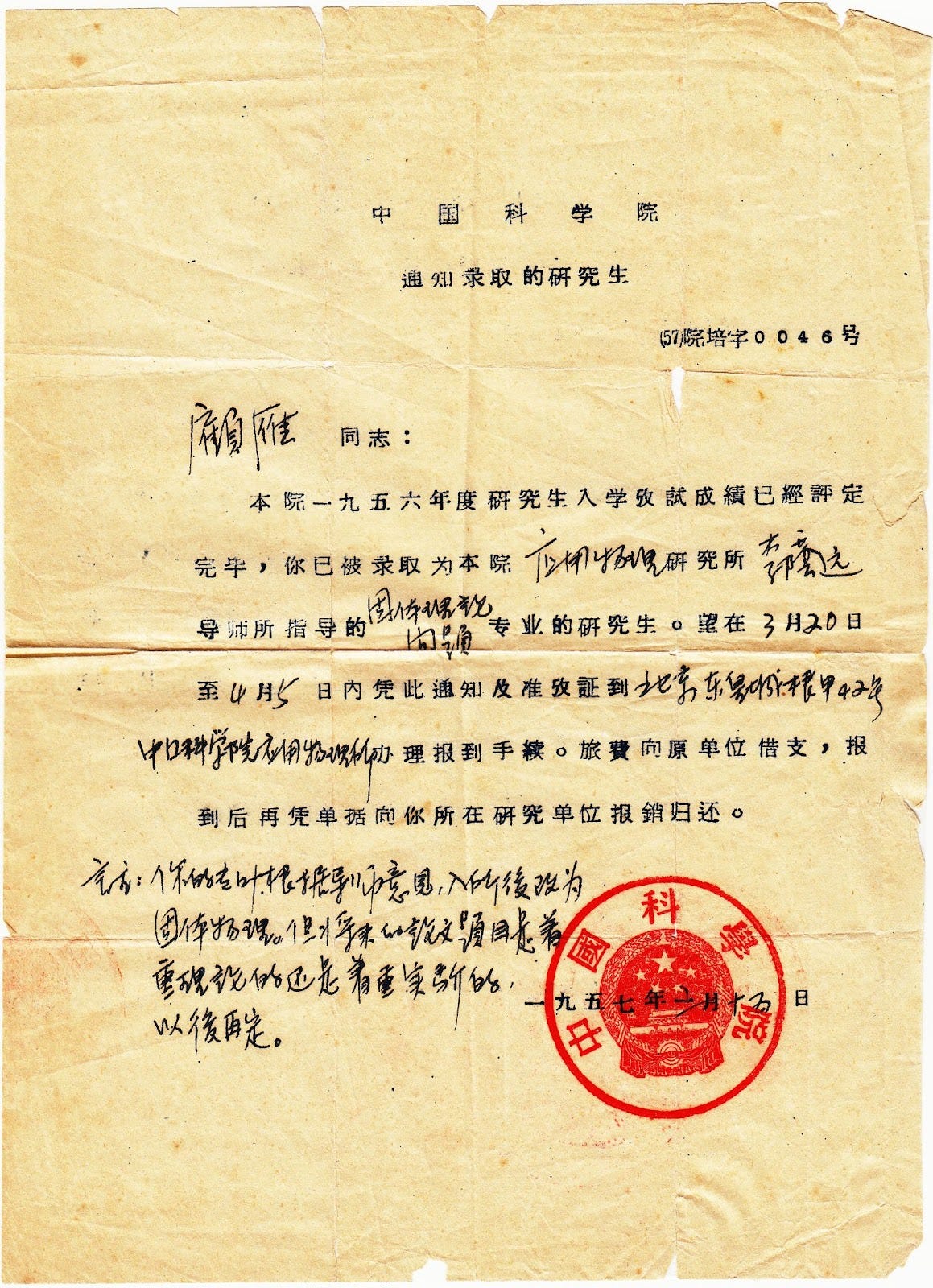

古汉语里,九十岁被称为“鲐背之年”,喻义高寿有福。而出生于1935年的顾雁,一生坎坷——作为上海世家子弟,18岁时去北京大学物理系求学,1957年读研究生时在兰州大学被打成右派,下放天水劳动时因发起创办地下刊物《星火》,与林昭同案而被重判17年,1974年减刑出狱时,已近40岁。

于最残酷的年代幸存,走出监狱的顾雁,又度过了漫长的50年人生。到今天,经历过癌症手术与妻子早逝,无儿无女的他,如一只孤雁,于暮色中回望一生时,林昭,依然是他此生最深切的怀念。然而,数十年来,他将这份怀念埋藏心中,很少在公开场合谈论自己与林昭的关系。直到今年8月,中国民间档案馆独家刊发了他的回忆长文——《我与林昭:“她走上了夏瑜的道路》(上篇及下篇),这是顾雁首次对公众全面讲述自己与林昭的关系,以及林昭与星火案的关联。这篇3万字的长文,也是尚未出版的《顾雁回忆录》中的一部分。

1981年“星火案”平反之后,顾雁即全心投入物理学研究——一方面,这是他青年时的梦想,另一方面,也是为了完成那个在林昭死去之后,对自己的誓言:要对人类有所贡献,以摆脱“偷生者”的耻辱,让自己的生命“复活”。这可能也是1949年后中国那些政治反抗幸存者共有的命运——他们一生都无法放下“幸存者”这个精神重负。对顾雁来说,重负之外,也有沉痛的深情:1981年,46岁的他终于要结婚了,他向母亲索要那枚原本留给林昭的翡翠,并和新婚的妻子,一起专程去了苏州林昭的墓前祭奠。

顾雁和林昭在1960年1月于上海初次相见,当时顾雁25岁,林昭28岁。他们的感情在夏天升温,但到秋天就不得不诀别——1960年10月“星火案”发后,他们在上海和苏州分别被抓,从此再无相见的机会。1968年4月,林昭被杀害,生命永远定格在36岁。

一直到今天,林昭依然是中国政治的一个禁忌。她苏州灵岩山的墓前,布满摄像头,近些年,监控更为严厉,时有人因为去祭奠她而遭抓捕。她的名字,已成了中国人追求民主、自由的一个象征。艺术家严正学为她创作了雕塑,头像坚定、俊美,脖颈则被重重铁链缠绕。

或许是因为林昭作为一个抗争者的形象,在人们心头的烙印太重,加之最终导致她被判20年重刑的案由起因是“星火案”,这让很多人以为她参与创办了《星火》这份地下刊物。但事实上,作为1960年代初当局炮制的一个“反革命大案”,星火只是重判林昭的一个由头。林昭与星火的关系若即若离,她真正有行动意味的政治反抗,实际上发生在星火同道被抓,但只有她一个人被保外就医并回到苏州之后。

“我不止一次地对来访的朋友说过,是我害了林昭。而我们之间选择的不同在于,我的抗争行动,到进监狱后就结束了。但她却从迈出监狱开始,一直到拼死抗争,献出生命。”顾雁曾在《我与林昭》长文中如是写道。

星火案发后,直接被牵连进去的有40多人。林昭对《星火》涉及不深,但为何被重判20年?为何她在第一次被抓后,于1962年3月保外就医、本可能自保平安的情况下,反而一改过去随性的态度,更为积极地活动,导致在8个月后再次入狱,乃至最后被杀害?这些问题,在顾雁的这篇回忆长文中,都能找到一些答案。

作为《星火》的创刊人以及整个案件的亲历者,顾雁的回忆与叙述,不仅厘清了一些关键事实,也让那个时代政治反抗者的形象,以及他们所处的历史环境更加清晰和立体——政治反抗运动需要更多元的叙述,这也是本文想表达的主旨之一。

1. 于《星火》,林昭犯的不过是“写诗罪”

“林昭与星火的关系,其实始终若即若离,最多算是思想上的同道。”顾雁回忆。

1959年的秋天,甘肃天水的东泉(今马跑泉)镇拖拉机站内,顾雁和张春元第一次将林昭的长诗《海鸥》刻印了数份,并在朋友中流传。在信息封闭的年代,这首诗能从上海传到大西北的甘肃天水,是因为另一位兰大右派学生孙和,其妹孙复是林昭的同班同学。此时,大饥荒已爆发,张春元、顾雁等人在酝酿要做点什么,这首诗中的反抗精神让他们如获至宝。但据顾雁回忆,曾经当过军人的张春元,对诗中“不自由毋宁死”的情感,虽然赞成,但觉得有点“浮夸”,他认为当下最重要的是要有一些实际的行动。

一个流传的说法是林昭的《海鸥》长诗刊发在星火的第一期,事实并非如此。对“西北的朋友们”在她并不知情的情况下刻印这首诗,林昭甚至颇不以为然,1961年10月,在看守所写下的《个人思想历程的回顾与检查》一文中,林昭曾提及此事,言下之义,她并不赞成这样的方式。

顾雁回忆,林昭确实没有参与星火的酝酿、筹划,但因为这首诗,让大家彼此产生了精神上的共鸣与连接。也让他们认识到,在中国,还有像他们一样关心着国家命运的人存在。两三个月后,张春元就以出差的名义(他因为有修理技术,被安排在拖拉机站工作,有一定的自由)去了上海,并找到了林昭。这次张春元带回了林昭的另一首长诗《普罗米修斯的最后一夜》。

和《海鸥》一样,林昭的这首长诗中,也有囚徒的意象:盗火者普罗米修斯,为了光明的火种,不惜与宙斯对抗,陷入万劫不复的深渊。如此热情刚烈的诗歌,却被林昭用秀丽的笔迹,写在精致的信纸上,可以折叠放入口袋,这让顾雁记忆深刻。

拿到诗后不久,张春元、顾雁、苗庆久、胡晓愚四人在天水背道(今麦积区)开会,明确了分工。12月,《星火》第一期诞生,刻印的地方在天水武山县————向承鉴和苗庆久在这里劳动。《普罗米修斯的最后一夜》也在《星火》第一期中,这可以说是林昭与星火最直接的关联。如帮助顾雁整理回忆录的艾晓明所说,“林昭在星火案中,所犯的其实就是写诗罪。”

不过极权之下,写诗本身就有它的意义。就如顾雁说,林昭的这两首诗,让他和张春元认识到,“在中国的土地上,确实有一些青年朋友,愿意为改变不合理的现实而牺牲。”而这个认知,对《星火》的诞生产生了直接的影响。

但因前述原因,林昭是《星火》创办者的说法至今流传,也出现在各种文献中。据顾雁介绍,《走近林昭》(2007年,明报出版社)一书中附录的《林昭年表》中也采用了这个说法。

事实上,不光是后来的研究者,就是林昭的同道朋友,对她这一段历史,也并不了了。例如,曾以未婚夫身份去监狱探视林昭的张元勋,在回忆文章中写到林昭的被捕时,也语焉不详:“林昭回到上海后生活在母亲、妹妹身边,疗、养皆好,日渐康复。她体力稍好,便常到图书馆、公园,逐渐结识了几位青年友人,往还渐繁,不免语涉国事……他们写成文字,上书北京,交邮寄出未久,上海公安局静安分局便派人去苏州将林昭逮捕(此时林昭在苏州家中养病)。”

2. 当时的林昭并不主张“无谓的牺牲”

按照顾雁的回忆,林昭确实看到了《星火》杂志。那是1960年1月他们初次在上海复兴公园见面,他给她带去了一份不久前刚在天水刻印出来的《星火》,但林昭当时并不以为意,甚至没有当面打开看,只是放到了一边。此后他们再见面,以及后来往来书信数十封,也没有提及此事(见《顾雁:缄默的星火灵魂》)。

林昭对《星火》的态度为何如此?40多年后,顾雁看到林昭于保外就医之前,在看守所写下的《个人思想历程》一文,也才更明白了她的态度。关于“大西北的朋友”刻印她的诗,她说:“在京时我曾手抄以传阅和赠送过,那个,另一回事,那还勉强可以算在合法的范围里,至多你来批判我这诗便是了。一到印刷,虽是油印,亦总有点哗众取宠、惊世骇俗。一副像煞有介事之态,其实又没啥了不起,‘鞋子不着落个样,月亮里点灯空挂名’,我不为也!”

对此,顾雁的感觉是:“由于我的刻印,她的诗从地下写作变成了公开写作,她认为这不是相得益彰而是相反,作者和读者都受其害。”他也忆及,当年他们准备将张春元的《论人民公社》刻印出来,传递到高层干部手里,在林昭看来,似乎也是老生常谈,并没有什么价值。而且“她认为我们误解她了,以为她是怕,但她并不是怕——不参与,是因为不值得,不值得便不干”。事实上,在《个人思想历程》中,她也是这么写的:“可我这种主张曾受到误解,使得我相当生气——已经走到了这么一步,难不成我还惜此一身么?”

顾雁认为,林昭当时这样写,一方面有可能是为了减罪而避重就轻的考虑——毕竟这是一份在看守所内写的检查,但更多的,也是她当时真实的心理。

艾晓明则认为,林昭当时的这种态度,其实并不奇怪。反右之后,林昭的心境其实颇为悲观——反右前,她曾在北大参加学生刊物《红楼》与《广场》的各种活动,反右之后,她的这些同仁,都遭遇到巨大的打击,例如和她关系密切(两人甚至曾计划结婚)的学弟甘粹,就被发配到新疆劳动教养20年。1957年冬天她在北大与张元勋告别时,所说的话就非常沉痛,“情况已到了最严重的关头,我们都要时刻做好被捕的思想准备。”而她,实际上是并不主张无谓的牺牲的。

上海初见,顾雁感受到了林昭对《星火》的态度,后来还和张春元一起交流过此事。但这不影响他们之间的彼此欣赏——他和她的政治观点,似乎也不用谈论太多,彼此都是明白的。从1960年四、五月开始,他们的交往密切起来,但因为林昭带回家藏在抽屉里的那份《星火》被母亲看见,母亲怕她再受影响,要求她回苏州老家去。据顾雁回忆,接下来的几个月,他们之间的信件往来十分密切。有时,一封信还没有回复,林昭的另一封信已经到了。“林昭的个性也是如此。不让她做的事情,她是偏要做的。”顾雁说。

如今看来,1960年夏天的那几个月,可能是林昭一生中最平和与舒缓的一段日子——她和顾雁交往,书信热烈,也像男女朋友一样约会,有时在苏州,有时在上海,两人约在公园见面,林昭有时还会带上一些点心来。

1960年9月,谭蝉雪在广东偷渡被发现,张春元前去营救,引起怀疑被抓,“星火案”发,一个多月后,顾雁在上海被捕,随后,林昭在苏州被捕。

被逮捕前,顾雁已察觉到身边出现密哨,他烧掉了其他的文字和信,但舍不得林昭的信,所以留了下来,和油印机等东西藏在老家的阁楼里,最终,这些东西都被公安搜走。顾雁认为,林昭的这三、四十封信,至今应该都在他的案卷里——不过他认为,这些信件,虽落入公安手中,但不足以增加林昭的罪责,却能反面证明,她确实和《星火》同仁的策划与行动并没有关系。

3. “对林昭来说,道德上的清白比什么都重要”,“她不愿意一个人被放出来”

1962年3月5日,经母亲的活动,林昭被保外就医。顾雁后来看到彭令范的回忆《我的姐姐林昭》一文中描述,林昭当时拒绝跟来接她的母亲和妹妹回家,并且十分激烈。“姐姐拖住了桌子腿执意不走,我和母亲根本拉她不动。最后由母亲请一位朋友家里的花匠来,硬把她按上三轮车载回家里。”

“1962年3月5日(开始)保外就医时的林昭,和之前与我们的政治活动保持距离的林昭完全不一样了,和《思想历程》里的林昭相比,简直可以说有一百八十度的转变。保外后她不仅没有安稳下来,而且行动更激进了。”顾雁在《我与林昭》中写道。

他也曾一直思索林昭为什么会发生那么大的变化,结合他1975年刑满后回到上海探亲,以及1980年平反以后逐步了解到的情况,他的分析是:林昭在得知保外时,没料想到,所有同案犯中,其他人都还被关押在里面,单独把她释放了。她将此举看作对她人格的巨大侮辱,因而坚决拒绝出狱。

“林昭就是这样,道德上的清白比什么都重要,这在她人生中是第一位的,不能有一点污点。所以她出来后第一步到我家,就是要表明这个态度:把我放出来,顾雁没有放出来,不是因为我写检讨,跟他们划清了界限。我是想在里边的,我不愿意一个人被放出来。”顾雁回忆。

保外就医出来后的林昭,第一时间就去了顾雁家里看望他的家人。在那以后,她多次去顾家,顾雁的父亲生病,她带去点心,有时还帮着捶背、照顾老人。她给全家人都留下了深刻又美好的印象。对这一部分,顾雁的母亲(父亲在顾雁服刑期间去世)和妹妹顾麋,都提供了佐证。

顾雁回忆倪竞雄(林昭的闺蜜)也曾跟他讲过,说林昭释放后去找她,看上去有很大的变化。“林昭从她母亲那里,肯定知道张春元在1961年越狱后,也是从甘肃到苏州,一路找过来。他到上海我家里去找我,又到苏州去找她。林昭出来以后,她也是同样如此,她要找到我们其他人的下落。结果得知,只把她放出去了,我还关在里边,其他人也都关在里边——这是她不能接受的。”顾雁回忆。

顾雁记得,那时他还关在上海的看守所,一次,妹妹顾麋来探监时,告诉了他林昭去家里的事。这深深触动了他的心,会见完之后,他第一次流了很久的泪。

不久之后,为了保护林昭,母亲还是让她去苏州。但到苏州后,林昭很快和当地的黄政、朱红等有反抗思想的青年过从密切起来。这一次,他们开始讨论一些星火同仁想做而没有做的事情。抓捕很快来临,1962年12月,林昭二次入狱,被指控在苏州当地进行“中国自由青年战斗联盟”的活动。

1965年,“星火案”宣判,在上海,顾雁、梁炎武(顾雁的同学,仅仅替谭蝉雪和张春元传递过信息)和林昭同案,但林昭的刑期最重,主要是因为她在保外就医这段时间的经历。顾雁回忆,他们三人的判决书只有一个,但针对林昭,还另有一份单独的起诉书。这份判决书中,林昭被称为“中国自由青年战斗联盟”反革命集团的主犯。

事实上,根据顾雁的回忆,审理此案的上海静安区法院,不仅把《星火》与1962年林昭保外期间的活动,杂糅在一起,还把林昭已二次入狱8个月后,由当局的线人张茹一联络参与在苏州的事情,“一锅烩”成了一个“反革命集团大案”,给林昭作出了20年的重判。

4. 张春元四去上海:官方曾以林昭为诱饵,试图找出“大哥”

顾雁回忆,当时他和梁炎武一直是被羁押状态,只有林昭在1960年3月5日至11月是保外就医。而判决到1965年才做出,就是静安分局要扩大战果,继续布网。当局认为破案计划未完成,即使张春元归案了,但当初为《海鸥》长诗写跋的那个“鲁凡”究竟是谁,是不是林昭口中的“大哥”,他们要继续找。所以才有被安插在林昭监室的的线人张茹一,又来顾家找顾麋,还有一个自称是“彭德怀的部下”的人,去顾家租房等等。官方疑神疑鬼,以为另有一个幕后黑手“大哥”存在,而事实上,“大哥”不过是林昭对张春元的称呼而已。

张春元是《星火》的灵魂人物。在顾雁眼里,他是一个有政治理想的人,也是“实干家”。今天回望,其实就是在《星火》内部,同一时期的这些政治反抗者,也有不同的层面。他们那时都还很年轻,每个人的理想和抱负并不相同,曾经上过朝鲜战场的张春元,没有顾雁、向承鉴等人的“书生气”,也更加“胆大”,1961年他被捕后,就曾借病越狱,不幸的是半个多月后被抓回。

从顾雁的回忆长文可以看到,张春元在《星火》前后曾至少去过四次上海。

第一次是1959年八、九月间,张春元在看到《海鸥》长诗后,知道林昭是同道,所以借出差的机会去了上海见林昭,两人相谈甚欢。但林昭对张春元所说的油印文章等事情,并没有表现出太大的兴趣。

第二次则是在1960年春天,大约三、四月间,张春元来到上海,约了顾雁、林昭一起在饭店吃饭,还泛舟湖上。那次张春元告知大家他和谭蝉雪已经订婚的消息,林昭喝了不少的酒。

第三次,是《星火》已经面世,但尚未暴露,谭蝉雪打算从广东偷渡出境,张春元路过上海,并告诉顾雁,他为了不拖累谭蝉雪,在上海给自己做了结扎手术。顾雁由此看到张春元愿意为理想牺牲的决心。

第四次,张春元再到上海时,已是他成功越狱之后。他来到上海,去了顾雁家里,见到了顾雁的父母,以及妹妹顾麋。在林昭被关押的看守所外,他曾徘徊良久,还寄去了一张明信片,以隐晦的语句,告诉她自己来过。

过后不久,张春元就被再次被抓入狱。在狱中,他的抗争也没有结束。一直到1970年“一打三反”的严酷形势下,与另一位星火同案杜映华同时期被杀害。

5. 政治反抗的多元叙述

1968年,顾雁在狱中得知了林昭已经遇害的消息,他给父亲写信,难以明言,只能含蓄地说,“林昭走上了夏瑜的道路。”

从顾雁的回忆可以看出,林昭这样一个决绝而彻底的政治反抗者,其实并不是一开始如此,而是也有自己的心路历程。

林昭也曾很热情地投入共产主义革命。作为一个曾经认同党的身份的人,她对党犯下的种种错误,曾经可以说是“爱之深,痛之切”,而并不是真正的反对立场。顾雁回忆中提到的,林昭曾写诗“为斯大林之死哭泣”,他就觉得不可思议。他深受自己家庭的影响,从未有“红”的一面,当年在北大求学时,他就被认为是属于“染不红的那一类人”。对他来说,终身的追求主要还是在学术上。“不是我去找政治,而是政治来找我。”可以说,他和林昭在成长经历、个人志趣、理想方面,其实都有很大不同。

顾雁回忆录的整理者艾晓明则认为,政治反抗原本就应该被多元叙述。每个参与政治反抗的人,其思想、动机,以及投入的程度也是不一样的。张春元、顾雁、向承鉴、谭蝉雪等人,他们当时参与《星火》的认同程度、长远考虑也是不一样的。每个人的叙述不一定完全吻合,这其实正是政治反抗中个人生命故事的真相。

对顾雁来说,和林昭短短数月的交往,却让他怀念了她一生。而这仿佛就要埋没于历史和岁月烟尘中的故事,行至生命的暮年,他终于开始讲述。除了《星火》,除了他们对极权的反抗,他们之间的情感往事,也是这段历史记忆中珍贵的一部分。

作为诗人的林昭,感情世界细腻而丰富。在当时封闭的环境中,她对两性的交往持一种比较开放的态度。她曾经和不同的男性友人,有过情感互动。而她与顾雁相识的那段时间,甘粹已下放新疆,其他人也成往事,巨大的暴风雨尚未袭来,他们的感情里有很多动人的时刻。在顾雁的回忆里,能看到一个爱耍小性子的林昭,温情可爱的林昭,还有她的任性与倔强——当他知道大祸降至、找她去说分手时,她还不以为然,塞给他评论《长恨歌》的文章。当他在狱中,得知她去了自己家里时,十分难过——他知道了她心中有他,这也让他认为,她曾经说过的《情书一束》,收信人应该是他。

今日林昭的名字已经成为一种公共的记忆。而经由顾雁的回忆,人们能看到,林昭这样一个极权下的不屈抗争者,也有过平凡的一面。她的一颦一笑,那长存于顾雁记忆中的私人情愫,让人们看到,在悲愤彻底的反抗之外,林昭曾是一个如此美好的女性,而极权体制对这美好生命的毁灭与摧残,才如此让人痛心。

本期档案推荐:

顾雁:《我与林昭:“她走上了夏瑜的道路》(上篇及下篇)

Political Resistance Requires a Plurality of Narratives: The Significance of Gu Yan’s Memoir, “Lin Zhao and Me”

By Jiang Xue

In August, the sweltering heat in Hefei, Anhui Province, had not yet subsided. At an old residential building on the East Campus of the University of Science and Technology of China, Gu Yan, just discharged from the hospital, celebrated his 90th birthday surrounded by younger friends.

Born in 1935 to a prominent Shanghai family, Gu Yan was admitted to Peking University’s Physics Department in 1952. While a graduate student at Lanzhou University, he was labeled a “Rightist.” During his forced labor in Tianshui, he co-founded the underground publication Spark and was sentenced to 17 years in the same criminal case as Lin Zhao. By the time his sentence was reduced and he was released from prison in 1974, he was nearly 40.

Having survived that brutal era, Gu Yan has lived another 50 years. Today, having endured cancer and the early death of his wife, Gu Yan, who does not have children, looks back on his life, in which Lin Zhao remains his most profound memory.

Gu wrote about these feelings in his memoirs, which the China Unofficial Archives has exclusive access to and partially published in two excerpts, on August 26 and August 27. Although he has given interviews before, these are his first in-depth and systematic explorations of his view of the Spark case and his feelings for Lin Zhao. They form part of a larger work that will be published in the near future.

In this essay, I want to discuss these two excerpts, which together were more than 30,000 characters, and explain their significance. Although Lin Zhao is synonymous with dissent in the Mao era and may well be the most famous dissident of that period, not all readers will be familiar with the relationship between Gu Yan and Lin Zhao, and might lack the background to see how his background illuminates key characteristics of dissent in China—then and now.

One key point that I discuss toward the end of this essay is the need for a plurality of narratives in how resistance is carried out. Not everyone has the same motives or ways of acting. This case is an example of that.

One of the first points worth explaining is why Gu Yan is writing now. After the Spark case was overturned in 1981, Gu Yan dedicated himself to physics research. It was partly his lifelong dream and partly to fulfill a vow he made to himself after Lin Zhao’s death: to contribute to humanity, to escape the shame of being a survivor, and to resurrect his own life.

This might be a common fate for many survivors of political resistance after 1949 in China; they carry the heavy psychological burden of being a survivor for the rest of their lives. For Gu Yan, this burden also came with deep and painful affection. In 1981, at 46, he was finally getting married. He asked his mother for a jade piece she had kept for Lin Zhao, and he and his wife made a special trip to Lin Zhao’s grave in Suzhou to pay their respects.

Gu Yan and Lin Zhao first met in Shanghai in January 1960. He was 25, and she was 28. Their relationship warmed in the summer but had to end in the fall. After the Spark case was exposed in October 1960, they were arrested separately in Shanghai and Suzhou and never saw each other again. In April 1968, Lin Zhao was executed, her life ending at 36.

Even today, Lin Zhao remains a political taboo in China. Cameras are stationed at her grave on Lingyan Mountain in Suzhou, and in recent years, surveillance has become even more severe. People are occasionally arrested for going to pay their respects. Her name has become a symbol for Chinese people’s pursuit of democracy and freedom. An artist created a sculpture of her with a firm and beautiful face, her neck wrapped in heavy iron chains.

Perhaps because Lin Zhao’s image as a dissident is so deeply ingrained, and because the case that led to her harsh 20-year sentence was the Spark case, many assume she helped found the underground publication Spark. However, in reality, Spark was merely the pretext for her heavy sentence in a fabricated “major counter-revolutionary case” by the authorities in the early 1960s. Lin Zhao’s relationship with Spark was tenuous. Her true political resistance occurred after her comrades were arrested and she alone was released on medical parole, returning to Suzhou.

“I have told visiting friends on more than one occasion that I harmed Lin Zhao. The difference in our choices was that my resistance ended when I entered prison. But her resistance started when she left prison and continued until she fought to the death and gave her life,” Gu Yan wrote in one of the essays published by the China Unofficial Archives.

After the Spark case was exposed, over 40 people were directly implicated. In Shanghai, Gu Yan was in the same case as Lin Zhao and Liang Yanwu; in Tianshui, Zhang Chunyuan, Tan Chanxue, Xiang Chengjian, Miao Qingjiu, and others were also involved. Lin Zhao was not deeply involved with Spark, so why was she sentenced to 20 years? Why did she, after being arrested and then released on medical parole in March 1962—when she could have ensured her safety—change her passive attitude and become more actively involved, leading to her re-imprisonment eight months later and her eventual death? The answers to these questions can be found in Gu Yan’s memoir.

1. Her Crime with Spark Was Merely Writing Poetry

“Lin Zhao’s relationship with Spark was always distant; at most, they were like-minded in their ideas,” Gu Yan recalls.

In the autumn of 1959, at the Dongquan (now Mapaoquan) Town Tractor Station in Tianshui, Gansu Province, Gu Yan and Zhang Chunyuan first duplicated and circulated several copies of Lin Zhao’s long poem, “The Seagull,” among their friends. In an era of information scarcity, this poem was able to travel from Shanghai to Tianshui in the remote northwest because another Rightist student from Lanzhou University, Sun He, had a sister, Sun Fu, who was Lin Zhao’s classmate. At this time, the Great Famine had erupted. Zhang Chunyuan, Gu Yan, and others were contemplating what to do, and they treasured the spirit of resistance in this poem. But according to Gu Yan, Zhang Chunyuan, a former soldier, agreed with the sentiment of “Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death” but found it a bit exaggerated, believing that the most important thing was to take concrete action.

A common rumor is that Lin Zhao’s long poem, “The Seagull,” was published in the first issue of Spark, but this is not the case. Lin Zhao was quite displeased that the “friends in the Northwest” had duplicated her poem without her knowledge. In an article she wrote in the detention center in October 1961 titled “A Review and Examination of My Personal Thought Process” (hereafter “My Thought Process”), Lin Zhao mentioned this incident, implying that she did not approve of the reprinting of her poems.

Gu Yan recalls that Lin Zhao did not participate in the deliberation or planning of Spark. However, because of the poem, they developed a spiritual resonance and connection, realizing that there were other people in China who cared about the country’s fate. Two or three months later, Zhang Chunyuan went to Shanghai on the pretense of a work trip and found Lin Zhao. This time, he brought back another long poem of hers, “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion.”

Like “The Seagull,” this long poem also had the imagery of a prisoner: Prometheus, the fire-stealer, who, for the sake of light, defied Zeus and fell into an abyss of eternal damnation. This passionate and fervent poem, written in Lin Zhao’s beautiful handwriting on delicate notepaper that could be folded and put in a pocket, left a deep impression on Gu Yan.

Shortly after receiving the poem, Zhang Chunyuan, Gu Yan, Miao Qingjiu, and Hu Xiaoyu held a meeting in Tianshui, where they clarified their roles. In December, the first issue of Spark was created. The duplication was done in Wushan County, Tianshui, where Xiang Chengjian and Miao Qingjiu were doing forced labor. “A Day in Prometheus’s Passion” was also in the first issue of Spark, which can be considered Lin Zhao’s most direct connection to the publication. As Ai Xiaoming, who helped Gu Yan organize his memoir, said, “Lin Zhao’s crime in the Spark case was, in fact, just writing poetry.”

However, under totalitarian rule, writing poetry itself has significance. As Gu Yan said, Lin Zhao’s two poems made him and Zhang Chunyuan realize that “on the land of China, there are indeed some young friends who are willing to sacrifice to change the unreasonable reality.” This realization had a direct impact on the creation of Spark.

But for the reasons mentioned above, the claim that Lin Zhao co-founded Spark is still circulating and appears in various documents. According to Gu Yan, the appendix of the book Getting Closer to Lin Zhao (2007, Ming Pao Press) also adopted this claim in its appendix “Lin Zhao Chronology.”

In fact, not only later researchers but even Lin Zhao’s comrades did not fully understand this part of her history. For example, Zhang Yuanxun, who once visited Lin Zhao in prison as her fiancé, was vague in his memoir about her arrest: “After returning to Shanghai, Lin Zhao lived with her mother and sister, and with good medical care and recuperation, she gradually recovered. As her physical strength improved, she often went to libraries and parks, gradually getting to know a few young friends. As their interactions became more frequent, they inevitably touched upon current affairs... They wrote things down, sent them to Beijing by mail, and not long after, the Jing’an police sub-bureau in Shanghai sent people to Suzhou to arrest Lin Zhao (at this time, Lin Zhao was recuperating at home in Suzhou).”

2. Lin Zhao Did Not Advocate for “Meaningless Sacrifice”

According to Gu Yan’s memory, Lin Zhao did see the Spark journal. It was in January 1960 when they first met in Fuxing Park in Shanghai. He brought her a copy of Spark that had been recently duplicated in Tianshui, but Lin Zhao didn’t pay much attention to it and didn’t even open it, just setting it aside. Afterward, in their subsequent meetings and dozens of letters, she never mentioned it again. (See “Gu Yan: The Silent Soul of Spark.”)

Why did Lin Zhao have such an attitude toward Spark? More than 40 years later, after reading the “My Thought Process” that Lin Zhao wrote in the detention center before her release on medical parole, Gu Yan came to a better understanding of her attitude. Regarding the “friends in the Northwest” who duplicated her poem, she wrote: “When I was in Beijing, I had hand-copied it to circulate and give away, but that’s a different matter. That could still be considered within a legal scope; at most, you could criticize the poem itself. But once it’s printed, even if it’s just mimeographed, it seems attention-seeking and sensational. It gives off a look of making a big deal out of it, when in fact it’s not a big deal at all. ‘A shoe without a sole is just for show, lighting a lamp on the moon is an empty name.’ I won’t do it.”

Gu Yan’s feeling about this was: “Because of my mimeographing, her poem went from underground writing to public writing. She believed this was not a mutually beneficial act but the opposite—that it would harm both the author and the readers.” He also recalled that when they were preparing to duplicate Zhang Chunyuan’s “On the People’s Commune” to be passed to high-level cadres, Lin Zhao seemed to find it a rehash of old ideas with no value. Moreover, “we misunderstood her; we thought she was scared, but she wasn’t—she didn’t participate because it wasn’t worthwhile. ‘If it’s not worthwhile, I won’t do it.’” In fact, she wrote the same thing in “My Thought Process”: “But my position was misunderstood, which made me quite angry—I’ve already come this far, would I still cling to my own life?”

Gu Yan believes that Lin Zhao might have written this to downplay her actions and get a lighter sentence, as it was a self-examination written in a detention center. But more importantly, it also reflected her true state of mind at the time.

Ai Xiaoming believes that Lin Zhao’s attitude at the time was not surprising. After the Anti-Rightist Campaign, Lin Zhao’s state of mind was quite pessimistic. Before the campaign, she had enthusiastically participated in student publications like Red Chamber and Plaza at Peking University. After the campaign, her colleagues, including her close friend and junior classmate Gan Cui (with whom she had planned to marry), were hit hard. Gan Cui was sent to a labor camp in Xinjiang for 20 years. In the winter of 1957, when she said goodbye to Zhang Yuanxun at Peking University, she spoke with great sorrow, saying, “The situation has reached a critical point. We must be mentally prepared for arrest at any moment.” She did not, in fact, advocate for meaningless sacrifice.

During their first meeting in Shanghai, Gu Yan sensed Lin Zhao’s attitude toward Spark, and he later discussed it with Zhang Chunyuan. But this didn’t affect their mutual admiration. There seemed to be no need to talk too much about their political views, as they understood each other. From April or May of 1960, their interactions became more frequent. However, because Lin Zhao’s mother found the copy of Spark that she had hidden in a drawer, she asked her to return to her hometown in Suzhou. According to Gu Yan, their correspondence was very frequent over the next few months. Sometimes, before he could reply to one letter, another one from Lin Zhao would have already arrived. “That was Lin Zhao’s personality. If you told her not to do something, she would deliberately do it,” Gu Yan said.

Looking back, those few months in the summer of 1960 were probably the most peaceful and relaxing period of Lin Zhao’s life. She and Gu Yan were seeing each other, their letters were passionate, and they dated like a couple. Sometimes they would meet in parks in Suzhou or Shanghai, and Lin Zhao would even bring some pastries.

In September 1960, one of the Tianshui students, Tan Chanxue, was caught while attempting to cross the border in Guangdong. Zhang Chunyuan went to rescue her, which aroused suspicion and led to his arrest. The Spark case was exposed. More than a month later, Gu Yan was arrested in Shanghai, and then Lin Zhao was arrested in Suzhou.

Before his arrest, Gu Yan had noticed secret surveillance around him. He burned other documents and letters but couldn’t bear to burn Lin Zhao’s letters, so he left them along with the mimeograph machine and other items hidden in the attic of his family home. Ultimately, all of these things were seized by the police. Gu Yan believes that those 30 to 40 letters from Lin Zhao should still be in his case file. However, he believes that these letters, while in the hands of the police, were not enough to increase Lin Zhao’s guilt but, on the contrary, could prove that she had no connection to the planning and actions of the Spark comrades.

3. “For Lin Zhao, Moral Integrity Was More Important Than Anything Else.” “She Wasn’t Willing to Be Released Alone.”

On March 5, 1962, through the efforts of her mother, Lin Zhao was released on medical parole. Gu Yan later read Peng Lingfan’s memoir, My Sister Lin Zhao, which described how Lin Zhao had fiercely refused to go home with her mother and sister who came to pick her up. “My sister held on to the table leg and refused to leave. My mother and I couldn’t pull her. Finally, my mother had to ask a friend’s gardener to force her into a three-wheeled rickshaw and take her home.”

“Lin Zhao, who was released on bail on March 5, 1962, was completely different from the Lin Zhao who had kept her distance from our political activities before. Compared to the Lin Zhao in ‘My Thought Process,’ she had undergone a 180-degree transformation. After her release, she didn’t settle down but became more radical in her actions,” Gu Yan wrote in “Lin Zhao and Me.”

He had always wondered why such a big change had occurred in Lin Zhao. Based on what he learned after his release in 1975, when he returned to Shanghai to visit his family, and gradually after his rehabilitation in 1980, his analysis is that when Lin Zhao learned she was being released on medical parole, she had not expected to be the only one let go while all her co-defendants were still being held. She saw this act as a great insult to her character and therefore adamantly refused to be released from prison.

“For Lin Zhao, moral integrity was more important than anything. It was her top priority in life, and there could not be the slightest blemish. That’s why her first step after being released was to go to my house to make a statement: ‘The reason I was released and Gu Yan wasn’t is not because I wrote a self-criticism and drew a line between myself and you. I wanted to stay inside. I didn’t want to be released alone,’” Gu Yan recalls.

After her release on medical parole, Lin Zhao went straight to Gu Yan’s home to visit his family. Afterward, she visited the Gu family multiple times. When Gu Yan’s father was sick, she brought pastries and sometimes helped him with back massages and took care of the elderly man. She left a deep and wonderful impression on the whole family. This is corroborated by Gu Yan’s mother (his father died while Gu Yan was in prison) and his sister, Gu Mi.

Gu Yan remembers Ni Jingxiong (Lin Zhao’s best friend) telling him that when Lin Zhao went to see her after her release, she looked like she had changed a lot. “Lin Zhao must have learned from her mother that after Zhang Chunyuan broke out of prison in 1961, he had traveled from Gansu to Suzhou, looking for her along the way. He had gone to my house in Shanghai to look for me, and then to Suzhou to find her. After Lin Zhao was released, she did the same thing; she wanted to find out where the rest of us were. When she found out she was the only one who had been released and that I and the others were still locked up, she couldn’t accept it,” Gu Yan recalls.

Gu Yan remembers that he was still being held in the Shanghai detention center at the time. One time, his sister Gu Mi came to visit him and told him about Lin Zhao’s visit to their home. This deeply moved him, and after their meeting, he cried for a long time for the first time.

Soon after, to protect Lin Zhao, his mother still made her go to Suzhou. But once in Suzhou, Lin Zhao quickly became close to local youths with anti-establishment ideas like Huang Zheng and Zhu Hong. This time, they began to discuss things that the Spark comrades had wanted to do but hadn’t. Arrests soon followed. In December 1962, Lin Zhao was imprisoned for a second time, accused of engaging in activities for the “Chinese Free Youth Militant League” in Suzhou.

In 1965, verdicts for the Spark case were handed out. In Shanghai, Gu Yan, Liang Yanwu (Gu Yan’s classmate who had only passed messages for Tan Chanxue and Zhang Chunyuan), and Lin Zhao were in the same case, but Lin Zhao received the harshest sentence, mainly because of her activities during her time on medical parole. Gu Yan recalls that there was only one verdict for the three of them, but there was also a separate indictment specifically for Lin Zhao. In this verdict, Lin Zhao was named the “principal culprit” of the “Chinese Free Youth Militant League” counter-revolutionary group.

In fact, according to Gu Yan’s recollection, the Jing’an District Court in Shanghai, which handled the case, not only conflated Spark with Lin Zhao’s activities during her parole in 1962 but also included her activities in Suzhou, which a police informant, Zhang Ruyi, contacted her about eight months after her second imprisonment. This created a “major counter-revolutionary case” and led to Lin Zhao’s heavy sentence of 20 years.

4. Zhang Chunyuan Went to Shanghai Four Times: The Authorities Used Lin Zhao to Find the “Big Brother”

Gu Yan recalls that he and Liang Yanwu were always detained, and only Lin Zhao was on medical parole from March 5 to November 1960. The verdict wasn’t delivered until 1965 because the Jing’an police sub-bureau wanted to expand their success and continue their network. The authorities believed that their investigation was incomplete. Even though Zhang Chunyuan had been apprehended, they still wanted to find out who “Lu Fan” was, the person who had written a postscript for “The Seagull,” and if he was the “Big Brother” that Lin Zhao had mentioned. This led to Zhang Ruyi, the informant placed in Lin Zhao’s cell, coming to Gu’s home to find Gu Mi, and a person who claimed to be “Peng Dehuai’s subordinate” renting a room at Gu’s home. The authorities were suspicious and believed there was a mastermind “Big Brother” at large. In reality, “Big Brother” was just Lin Zhao’s nickname for Zhang Chunyuan.

Zhang Chunyuan was the soul of Spark. In Gu Yan’s eyes, he was a man with political ideals and a pragmatist. Looking back today, it’s clear that even within Spark, these political dissidents had different facets. They were all very young then, and their ideals and ambitions differed. Zhang Chunyuan, who had fought in the Korean War, was not as bookish as Gu Yan or Xiang Chengjian, and he was bolder. After he was arrested in 1961, he escaped from prison by feigning illness, but was recaptured after about half a month.

From Gu Yan’s memoir, it can be seen that Zhang Chunyuan went to Shanghai at least four times before and after Spark.

The first time was in August or September 1959. After Zhang Chunyuan read the long poem “The Seagull,” he knew Lin Zhao was a kindred spirit. So he went to Shanghai to meet Lin Zhao, and they had a great conversation. But Lin Zhao didn’t show much interest in the mimeographed articles that Zhang Chunyuan talked about.

The second time was in the spring of 1960, around March or April. Zhang Chunyuan came to Shanghai and arranged to have a meal with Gu Yan and Lin Zhao at a restaurant, and they also took a boat ride on a lake. On that occasion, Zhang Chunyuan told them that he and Tan Chanxue were engaged, and Lin Zhao drank a lot of wine.

The third time was after Spark had been published but not yet exposed. Tan Chanxue was planning to cross the border from Guangdong. Zhang Chunyuan passed through Shanghai and told Gu Yan that he had undergone a vasectomy in Shanghai so that he would not be a burden to Tan Chanxue. Gu Yan saw Zhang Chunyuan’s determination to sacrifice, for Zhang Chunyuan did not want Tan Chanxue to have to care for children alone if he died.

The fourth time Zhang Chunyuan came to Shanghai was after his successful prison escape. He came to Shanghai and went to Gu Yan’s home, where he met Gu Yan’s parents and sister, Gu Mi. Outside the detention center where Lin Zhao was being held, he lingered for a long time and even sent her a postcard with cryptic words to let her know he had been there.

Shortly after, Zhang Chunyuan was arrested and imprisoned again. His resistance did not end in prison. He was killed in 1970 during the draconian “One-Strike, Three-Anti” campaign, at the same time as another Spark co-defendant, Du Yinghua.

5. The Plurality of Narratives of Political Resistance

In 1968, Gu Yan learned in prison that Lin Zhao had been killed. He wrote a letter to his father, unable to say it outright, only hinting that “Lin Zhao has walked the path of Xia Yu,” referring to a woman martyr in one of Lu Xun’s works.

From Gu Yan’s memoir, it’s clear that Lin Zhao, such a resolute and radical political dissident, was not like this from the beginning. She had her own psychological journey.

Lin Zhao had once enthusiastically thrown herself into the Communist revolution. As someone who once identified with the Party, her stance on the various mistakes the Party had made could be described as “deep love, deep pain,” not one of true opposition. Gu Yan recalls that Lin Zhao once wrote a poem “weeping for the death of Stalin,” which he found hard to believe. Influenced by his own family, he had never been “red.” When he was studying at Peking University, he was considered “the kind of person who couldn’t be dyed red.” For him, his lifelong pursuit was mainly academic. “I didn’t seek out politics; politics came looking for me.” It can be said that he and Lin Zhao were very different in their formative experiences, personal interests, and ideals.

Ai Xiaoming, who organized Gu Yan’s memoir, believes that political resistance should be told through a plurality of narratives. The thoughts, motivations, and level of commitment of each person involved in political resistance are different. The degree of their identification with Spark and their long-term considerations were also different for Zhang Chunyuan, Gu Yan, Xiang Chengjian, and Tan Chanxue. The narratives of each person do not necessarily match up perfectly, and this is precisely the reality of personal stories in political resistance.

For Gu Yan, the short few months he spent with Lin Zhao led to a lifetime of remembrance. And now, in the twilight of his life, he has finally begun to tell this story, which was on the verge of being lost to history and the dust of time. Beyond Spark and their resistance against totalitarian rule, their emotional history is also a precious part of this historical memory.

As a poet, Lin Zhao’s emotional world was delicate and rich. In the closed environment of the time, she had a relatively open attitude toward relationships between men and women. She had emotional interactions with different male friends. During the time she met Gu Yan, Gan Cui had already been sent to Xinjiang, and others were a thing of the past. The great storm had not yet arrived, and there were many moving moments in their relationship. In Gu Yan’s memoir, one can see a Lin Zhao who would get a little pouty, a warm and lovely Lin Zhao, and also her willfulness and stubbornness. When he knew that great disaster was coming and tried to break up with her, she didn’t take it seriously and instead handed him her article commenting on the poem “Song of Everlasting Sorrow.” When he was in prison, he was so sad to learn that she had gone to his home, which also made him believe that the “bundle of love letters” she had mentioned had been addressed to him.

Today, Lin Zhao’s name has become a public memory. And through Gu Yan’s recollections, people can see that Lin Zhao, as an unyielding opponent against totalitarian rule, also had an ordinary side. Her every smile and frown, those private feelings that have long lived in Gu Yan’s memory, show people that beyond her tragic and thorough resistance, Lin Zhao was a beautiful woman. The destruction and devastation of such a beautiful life by a totalitarian system is the real tragedy.

Recommended archives: